The Place of Abraham Lincoln in History

“We think we pay the best tribute to his memory and the most fitting respect to his name, if we ask after the relation in which he stands to the history of his country and his fellow-man.”

The funeral procession of the late President of the United States has passed through the land from Washington to his final resting-place in the heart of the Prairies. Along the line of more than fifteen hundred miles his remains were borne, as it were, through continued lines of the people; and the number of mourners and the sincerity and unanimity of grief were such as never before attended the obsequies of a human being; so that the terrible catastrophe of his end hardly struck more awe than the majestic sorrow of the people. The thought of the individual was effaced; and men’s minds were drawn to the station which he filled, to his public career, to the principles he represented, to his martyrdom. There was at first impatience at the escape of his murderer, mixed with contempt for the wretch who was guilty of the crime; and there was relief in the consideration, that one whose personal insignificance was in such a contrast with the greatness of his crime had met with a sudden and ignoble death. No one stopped to remark on the personal qualities of Abraham Lincoln, except to wonder that his gentleness of nature had not saved him from the designs of assassins. It was thought then, and the event is still so recent it is thought now, that the analysis and graphic portraiture of his personal character and habits should be deferred to less excited times; as yet the attempt would wear the aspect of cruel indifference or levity, inconsistent with the sanctity of the occasion. Men ask one another only, Why has the President been struck down, and why do the people mourn? We think we pay the best tribute to his memory and the most fitting respect to his name, if we ask after the relation in which he stands to the history of his country and his fellow-man.

Before the end of 1865, it will have been two hundred and forty-six years since the first negro slaves were landed in Virginia from a Dutch trading-vessel, two hundred and twenty-eight since a Massachusetts vessel returned from the Bahamas with negro slaves for a part of its cargo, two hundred and twenty years since men of Boston introduced them directly from Guinea. Slavery in the United States had not its origin in British policy: it sprung up among Americans themselves, who in that respect acquiesced in the customs and morals of the age. But at a later day the importation of slaves was insisted upon by the government of the mother country, under the influence of mercantile avarice, with the further purpose of weakening the rising Colonies, and impeding the establishment among them of branches of industry that might compete with the productions of England. Climate and the logical consequences of the principles of the Puritans checked the increase of slaves in Massachusetts, from which it gradually disappeared without the necessity of any special act of manumission; in Virginia, the country within the reach of tide-water was crowded with negroes, and the marts were supplied by continuous importations, which the Colony was not suffered to prohibit or restrain.

The middle of the eighteenth century was marked by a rising of opinion in favor of freedom. The statesmen of Massachusetts read the great work of Montesquieu on the Spirit of Laws; and in bearing their first very remarkable testimony against slavery, they simply adopted his words, repeated without passion, for they had no dread of the increase of slavery within their own borders, and never doubted of its speedy and natural decay. The great men of Virginia, on the contrary, were struck with terror as they contemplated its social condition; they drew their lessons, not from France, not from abroad, but from themselves and the scenes around them; and half in the hope of rescuing that ancient Commonwealth from the corrupting element of slavery, and half in the agony of despair, they went in advance of all the world in their reprobation of the slave-trade and of slavery, and of the dangerous condition of the white man as the master of bondmen. In the years preceding the war of the Revolution, the Ancient Dominion rocked with the strife of contending parties: the King with all his officers and many great slaveholders on the one side, against a hardy people in the hack country and the best of the slaveholders themselves. On the side of liberty many were conspicuous, among them Richard Henry Lee, George Wythe, Jefferson, who from his youth was the pride of Virginia; but all were feeble in comparison with the enthusiastic fervor and prophetic instincts of George Mason. They reasoned, that slavery was inconsistent with Christianity, was in conflict with the rights of man; that it was a slow poison, daily contaminating the minds and morals of their people; that, by reducing a part of their own species to abject inferiority, they lost the idea of the dignity of man, which the hand of Nature had implanted within them for great and useful purposes; that, by the habit from infancy of trampling on the rights of human nature, every liberal sentiment was extinguished or enfeebled; that every gentleman was born a petty tyrant, and by the practice of cruelty and despotism became callous to the finer dictates of the soul; that in such an infernal school were to be educated the future legislators and rulers of Virginia. And before the war broke out, the House of Burgesses of Virginia was warned of the choice that lay before them: either the Constitution must by degrees work itself clear by its own innate strength and the virtue and resolution of the community, or the laws of impartial Providence would avenge on their posterity the injury done to a class of unhappy men debased by their injustice.

At the opening of the war of the Revolution, the Narragansett country of Rhode Island, the Southern part of Long Island, New York City and the counties on the Hudson, and East New Jersey had in their population about as large a proportion of slaves as Missouri four years ago. In all the Colonies collectively the black men were to the white men as five to twenty-one. The British authorities unanimously held that the master lost his claim to his slave by the act of rebellion. In Virginia a system of emancipation was inaugurated; and the emancipation of slaves by success in arms Jefferson pronounced to be right. But the system of emancipation took no large proportions: partly because the invaders in the beginning of the war were driven from the Chesapeake; partly because the large slaveholders of South Carolina, on the subjugation of the low country in that State, renewed their allegiance to the Crown; and partly because British officers chose to ship slaves of rebels to the markets of the West Indies. Yet the continued occupation of Rhode Island, Long Island, and New York City, and the exodus of slaves with other refugees at the time of peace, facilitated the movements in Rhode Island and New York for the abrogation of slavery. At the end of the war the proportion of free people to slaves was greatly increased; and, whatever willful blindness may assert, the free black had the privileges of a citizen.

Here, then, was an opening for relieving the body politic from the great anomaly of bondage in the midst of freedom. But though divine justice never slumbers, the opportunity was but partially seized. The diminution of the number of laborers at the South revived the importation of slaves. The first Congress had agreed not to tolerate that traffic; the Confederacy left its encouragement or prohibition to the pleasure of each State; and the Constitution continued that liberty for twenty years. At the same time slavery was excluded from the whole of the territory of the United States. The vote of New Jersey only was wanting to have sustained the proposition of Jefferson, by which it would have been excluded not only from all the territory then in their possession, but from all that they might gain.

The jealousy of the Southern States of the power of the North may be traced through the annals of Congress from the first, which assembled in 1774. The old notions of the independence and sovereignty of each separate State, though the Constitution was framed for the express purpose of modifying them, clung to life with tenacity. When John Adams was elected President, before any overt act, before any other cause of alarm than his election, the Legislature of Virginia took steps for an armed organization of the State, and old and long-cherished sentiments adverse to Union were renewed. The continuance of the Union was in peril. It was then that the great Virginia statesman, now perfectly satisfied with the amended Constitution, came to the rescue. By the simple force of ideas, embodying in one system all the conquests of the eighteenth century in behalf of human rights, the freedom of conscience, speech, and the press, he ruled the willing minds of the people. The South, where his great strength lay with the poor whites, and where he was known as the champion of human freedom, trusted in his zeal for individual liberty and for the adjusted liberty of the States ; the North heard from him sincere and consistent denunciations of slavery, such as had never been surpassed, except by George Mason. The thought never crossed the mind of Jefferson that the General Government had not proper powers of coercion. On taking the office of President, his watchword was, We are all Federalists, we are all Republicans; and the two principles of universal freedom and equality, and the right of each State to regulate its own internal domestic affairs, became not so much the doctrine of a party as the accepted creed of the nation. In his administration of affairs, Jefferson did not suffer one power of the General Government to be weakened. No one man did so much as he towards consolidating the Union.

But the question of Slavery was not solved. The purchase of Louisiana increased the States in which slaves were tolerated; the settlement of the Northwest strengthened the power of freedom; but as yet there had been no fracture in public opinion. Missouri asked to be admitted to the Union, and it was found, that, without any party organization, without formal preparation, a majority of the House of Representatives desired to couple its admission with the condition that it should emancipate its slaves. That slavery was evil was still the undivided opinion of the nation; but it was perceived that the friends of freedom had missed the proper moment for action, that Congress had tolerated slavery in Missouri as a Territory, and were thus inconsistent in claiming to suppress slavery in the State; and they escaped from the difficulty by what was called a Compromise. It was agreed that for the future slavery should never be carried to the north of the southern boundary of Missouri; and this was interpreted by the South as the devoting of all the territory south of that line to the owners of slaves.

From that day Slavery became the foundation of a political party, under the guise of a zeal for the rights of States. It began to be perceptible at the next Presidential election; but Calhoun, who was willing to be considered a candidate for the Presidency, was still as decidedly for the Union as John Quincy Adams or Webster. Walking one day with Seaton of the “Intelligencer” on the banks of the Potomac, Seaton dissuaded him from being at that day a candidate for the Presidency, giving as a reason, that, in case of success and reelection, he would go out of the public service in the vigor of life. “I will, at the end of my second term, go into retirement and write my memoirs,” was Calhoun’s answer: a proof that at that time Disunion had not crossed his mind.

The younger Adams had been undoubtedly at the South the candidate of the Union party. The incipient opposition to Union threw itself with the intensest heat into the opposition to Adams; and Jackson, who was victorious through his own popularity, was elected by a vast majority. Jackson was honest, patriotic, and brave: he refused his confidence to the oligarchical party, represented by Calhoun and Macduffie; and after passionate struggles, which convulsed the country, he defied their hostility, and told them to their faces, “The Union must be preserved.”

The bitterness of disappointed ambition led to the formation and gradual enunciation of new political opinions. In the strife about the practical effects of Nullification, the question was raised by the Nullifiers, whether obedience to the laws of a State was a good plea for resistance to the laws of the United States; and so, for the first time in our history, a political party came to the principle, that primary allegiance was due to the State, a secondary one only to the United States; and this view was taught in schools and colleges and popular meetings. The second theory, that grew up with the first, was, that slavery was a divine institution, best for the black man and best for the white.

At the election which followed the retirement of Jackson, the Democratic party stood by its old tradition of the evil of slavery, and the hope that by the innate vigor of the respective States it would gradually be thrown off; the opposite party likewise held to the same tradition, in the belief that the progress of commerce and domestic industry would in due time quietly remove what all sound political economy condemned. The new party, the party of State Sovereignty and Slavery, for the two heads sprung from one root, had not power enough to prevent the election of one who represented the policy of Jackson. But they were full of passionate ardor and of restless activity; and in the next Presidential election they threw themselves upon the Whig party, with which they joined hands. The Whig party was at that day strong enough to have done without them; but the uncontrollable wish for success, which had been long delayed, led to the cry of “Tippecanoe and Tyler too,” and this meant a union of the interests of the North with the interest of Slavery. Harrison had votes enough to elect him without one vote from the Southern oligarchy; but the compact was made; Harrison was elected and died, and the representative of the oligarchy, a man at heart false to the national flag, became President for nearly four years.

His administration is marked by the annexation of Texas to the United States: a measure sure, in the belief of Calhoun, to confirm the empire of Slavery, sure, as others believed, to prevent the foundation of an adventurous government, that, if left to independence, would have reopened the slave trade and subdued by force of arms all California and Mexico to the sway of Slavery. The faith of the last proved the true one. Under the administration of Polk, California was annexed, not to independent, slave-holding Texas, but to the Union. This constitutes the turning-point in the series of events; the first emigrants to her borders formed a constitution excluding slavery.

At the next election a change took place, profoundly affecting the Democratic party, and, as a consequence, the country. Hitherto the position of the Northern Democracy had been that of Jefferson, that slavery was altogether evil; and Cass, the Democratic candidate, still expressed his prayer for the final doom of slavery. Against his election a third party was formed; and Van Buren, a former Democratic President, who had been sustained by the South as well as by the North, taking with him one half the Democracy of New York, consented to be the candidate of that party. We judge not his act; but the consequences were sad. To the South his appearance as a candidate on that basis had the aspect of treachery; at the North the Democratic party lost its power to resist the arrogance of the South: for, in the first place, large numbers of its best men had left its ranks; and next, those who remained behind were eager to clear themselves of the charge of sectional narrowness; and those who had gone out and come hack, in their zeal to recover the favor of the South, went beyond all bounds in their professions of repentance. The old compromise of Jefferson fell into disrepute; the Democratic party itself was thrown into confusion; the power of any one of its distinguished men to resist the increasing arrogance of the slaveholders was taken away; a word in public for what twenty years before had been the creed of every one was followed by the ban of the majority of the party. So fell one bulwark against slavery.

Still another bulwark against it was destined to fall away. The annexation of California brought, with it the question of the admission of California as a State of freemen. The only way to have avoided convulsing the country was to have confined the discussion to the one question of the admission of California. Unhappily, Clay, truly representing a State which halted in its choice between freedom and slavery, proposed a combination of measures. Further, the representation of the Free States had steadily increased from the origin of the Government; the admission of California threatened, at last, to open the way for a corresponding disproportion in the Senate. The country, remembering how Webster, on a great occasion, had greatly resisted the heresy of Nullification, looked to him now to clear away the mists of artful misrepresentations of the Constitution, and show that neither in that Constitution nor in the history of the country at the time of its formation had there been any justification of the demand for such equality of representation. But this time the great orator failed; the passionate desire for being President led him to make a speech intended to conciliate the support of the South. In that he failed miserably at the moment; a few days later, Calhoun, on his deathbed, avowed himself the adviser of a secession of the whole body of the slaveholding States. Still blinded by ambition, Webster, on a tour through New York, as a candidate, formally proposed the establishment of a party representing the property of the country, crystallizing round the slaveholders, and including the commercial and corporate industrial wealth of the North. The effect on his own advancement was absolutely nothing. In due time, as a candidate, he fell stone dead; and it is to his credit that he did so. The South knew that he was a Union man, and would not answer their purpose. As he heard of the slight given by those whom he had courted, his large head fell on his breast, his voice faltered, and big tears trickled down his cheeks. His cheerfulness never returned; he languished and died; but the evil that lived after him was, that the great party to which he had belonged was no more able to stem the rising fury of the South, and broke to pieces.

Thus, by untoward circumstances, the truth that could alone confirm the Union, and which heretofore had been substantially supported by both the great traditional parties of the country, no longer had a clear and commanding exponent in either of them. The result of the next election showed that the old Whig party had lost all power over the public mind. The strife went on, and hope centred in the supreme judicial tribunal of the land, to whose members a secure tenure of office had been given, that they might be above all temptation of serving the time. The politicians of the North were becoming alarmed by the issues which were forced upon them by those of the South with whom they still wished to be friends; they longed to shift the responsibility of the decision upon the Supreme Court. The Court was slow to be swerved. The case of Dred Scott was before them; and the decision of the Court was embodied in an opinion which would have produced no excitement. But the Court was entreated to give their decision another form. They long resisted, and were long divided; but perseverance overcame them; and at last a most reluctant majority, a hare majority, was won to enter the arena of politics, and attempt the suppression of differences of opinion: for, said one of the judges, the peace and harmony of the country require the settlement of Constitutional principles of the highest importance, not knowing that injustice overturns peace and harmony, and that a depraved judiciary portends civil war.

The man who took the Presidential chair in 1857 had no traditional party against him; he owed his nomination to confidence in his moderation and supposed love of Union. He might have united the whole North and secured a good part of the South. Constitutionally timid, on taking the oath of office, he betrayed his own weakness, and foreshadowed the forthcoming decision of the Supreme Court. Under the wing of the Executive, Chief-Justice Taney gave his famed disquisition. The delivery of that opinion was an act of revolution. The truth of history was scorned; the voice of passion was put forward as the rule of law; doctrines were laid down which, if they are just, give a full sanction to the rebellion which ensued. The country was stung to the quick by the reckless conduct of a body which it needed to trust, and which now was leading the way to the overthrow of the Constitution and the dismemberment of the Republic. At the same time, the President, in selecting the members of his cabinet, chose four of the seven from among those who were prepared to sacrifice the country to the interests of Slavery. In time of peace the finances were willfully ill-administered, and in the midst of wealth and credit the country was saved from bankruptcy only by the patriotism of the city of New York, against the treacherous intention of the Secretary of the Treasury. Cannon and muskets and. military stores were sent in numbers where they could most surely fall into the hands of the coming rebellion; troops of the United States were placed under disloyal officers and put out of the way; the navy was scattered abroad. And then, that nothing might be wanting to increase the agony of the country, an attempt to force the institution of Slavery on the people of Kansas, that refused it, received the encouragement and aid of the President. The conspirators resolved at the next Presidential election to compel the choice of a candidate of their own, or of one against whom they could unite the South; and all the influence of the Administration, through its patronage, was used to confine the election to that issue.

Virginia statesmen, more than ninety years ago, had foretold that each State Constitution must work itself clear of the evil of slavery by its own innate vigor, or await the doom of impartial Providence. Judgment slumbered no longer, though wise men after the flesh were not chosen as its messengers and avengers.

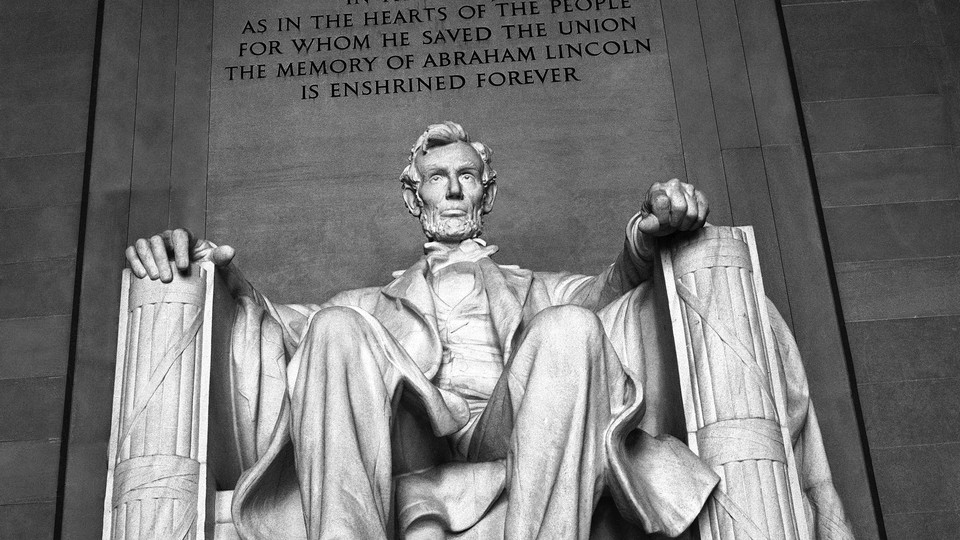

The position of Abraham Lincoln, on the day of his inauguration, was apparently one of helpless debility. A bark canoe in a tempest on mid-ocean seemed hardly less safe. The vital tradition of the country on Slavery no longer had its adequate expression in either of the two great political parties, and the Supreme Court had uprooted the old landmarks and guides. The men who had chosen him President did not constitute a consolidated party, and did not profess to represent either of the historic parties which had been engaged in the struggles of three quarters of a century. They were a heterogeneous body of men, of the most various political attachments in former years, and on many questions of economy of the most discordant opinions. Scarcely knowing each other, they did not form a numerical majority of the whole country, were in a minority in each branch of Congress except from the willful absence of members, and they could not be sure of their own continuance as an organized body. They did not know their own position, and were startled by the consequences of their success. The new President himself was, according to his own description, a man of defective education, a lawyer by profession, knowing nothing of administration beyond having been master of a very small post-~ office, knowing nothing of war but as a captain of volunteers in a raid against an Indian chief; repeatedly a member of the Illinois Legislature, once a member of Congress., He spoke with ease and clearness, but not with ~eloquence. He wrote concisely and to the point, but was unskilled in the use of the pen. He had no accurate knowledge of the public defences of the country, no exact conception of its foreign relations, no comprehensive perception of his duties. The qualities of his nature were not suited to hardy action. His temper was soft and gentle and yielding; reluctant to refuse anything that presented itself to him as an act of kindness; loving to please and willing to confide; not trained to confine acts of good-will within the stern limits of duty. He was of the temperament called melancholic, scarcely concealed by an exterior of lightness of humor, having a deep and fixed seriousness, jesting, lips, and wanness of heart. And this man was summoned to stand up directly against a power with which Henry Clay had never directly grappled, before which Webster at last had quailed, which no President had offended and yet successfully administered the Government, to which each great political party had made concessions, to which in various measures of compromise the country had repeatedly capitulated, and with which he must now venture a struggle for the life or death of the nation.

The credit of the country had not fully recovered from the shock it had treacherously received in the former administration. A part of the navy-yards were intrusted to incompetent agents or enemies. The social spirit of the city of Washington was against him, and spies and enemies abounded in the circles of fashion. Every executive department swarmed with men of treasonable inclinations, so that it was uncertain where to rest for support. The army officers had been trained in unsound political principles. The chief of staff of the highest of the general officers, wearing the mask of loyalty, was a traitor at heart. The country was ungenerous towards the negro, who in truth was not in the least to blame, was impatient that such a strife should have grown out of his condition, and wished that he were far away. On the side of prompt decision the advantage was with the Rebels; the President sought how to avoid war without compromising his duty; and the Rebels, who knew their own purpose, won incalculable advantages by the start which they thus gained. The country stood aghast, and would not believe in the full extent of the conspiracy to shatter it in pieces; men were uncertain if there would be a great uprising of the people. The President and his cabinet were in the midst of an enemy’s country and in personal danger, and at one time their connections with the North and West were cut off; and that very moment was chosen by the trusted chief of staff of the Lieutenant-General to go over to the enemy.

Every one remembers how this state of suspense was terminated by the uprising of a people who now showed strength and virtues which they were hardly conscious of possessing. In some respects Abraham Lincoln was peculiarly fitted for his task, in connection with the movement of his countrymen. He was of the Northwest; and this time it was the Mississippi River, the needed outlet for the wealth of the Northwest, that did its part in asserting the necessity of Union. He was one of the mass of the people; he represented them, because he was of them; and the mass of the people, the class that lives and thrives by self-imposed labor, felt that the work which was to be done was a work of their own: the assertion of equality against the pride of oligarchy; of free labor against the lordship over slaves; of the great industrial people against all the expiring aristocracies of which any remnants had tided down from the Middle Age. He was of a religious turn of mind, without superstition; and the unbroken faith of the mass was like his own. As he went along through his difficult journey, sounding his way, he held fast by the hand of the people, and tracked its footsteps with even feet. His pulse’s beat twinned with their pulses. He committed faults; but the people were resolutely generous, magnanimous, and forgiving; and he in his turn was willing to take instructions from their wisdom.

The measure by which Abraham Lincoln takes his place, not in American history only, but in universal history, is his Proclamation of January I, 1863, emancipating all slaves within the insurgent States. It was, indeed, a military necessity, and it decided the result of the war. It took from the public enemy one or two millions of bondmen, and placed between one and two hundred thousand brave and gallant troops in arms on the side of the Union. A great deal has been said in time past of the wonderful results of the toil of the enslaved negro in the creation of wealth by the culture of cotton; and now it is in part to the aid of the negro in freedom that the country owes its success in its movement of regeneration, that the world of mankind owes the continuance of the United States as the example of a Republic. The death of President Lincoln sets the seal to that Proclamation, which must be maintained. It cannot but be maintained. It is the only rod that can safely carry off the thunderbolt. He came to it perhaps reluctantly; he was brought to adopt it, as it were, against his will, but compelled by inevitable necessity. He disclaimed all praise for the act, saying reverently, after it had succeeded, “The nation’s condition God alone can claim.”

And what a futurity is opened before the country when its institutions become homogeneous! From all the civilized world the nations will send hosts to share the wealth and glory of this people. It will receive all good ideas from abroad; and its great principles of personal equality and freedom—freedom of conscience and mind, freedom of speech and action, freedom of government through ever renewed common consent will undulate through the world like the rays of light and heat from the sun. With one wing touching the waters of the Atlantic and the other on the Pacific, it will grow into a greatness of which the past has no parallel; and there can be no spot in Europe or in Asia so remote or so secluded as to shut out its influence.