Gestalt principles and its design applications

Human beings interact with number of different products every day. The information or signals from these products are processed by humans in stages. The signal is initially detected by biological receptors, then pre-attentively processed by the subconscious mind and finally processed cognitively. Researchers has conducted various studies to shows that certain features of an object like luminance, orientation, size, contrast, shape, texture, colors, different levels of contrast, line curvature, line misalignment, and proximity are processed pre-attentively (Treisman & Gelade, 1980; Treisman , 1982; Treisman & Gormican, 1988; Wolfe, Cave & Franzel, 1989; Wolfe, 1994; Moore & Egeth 1997; Prinzmetal & Banks, 1977).

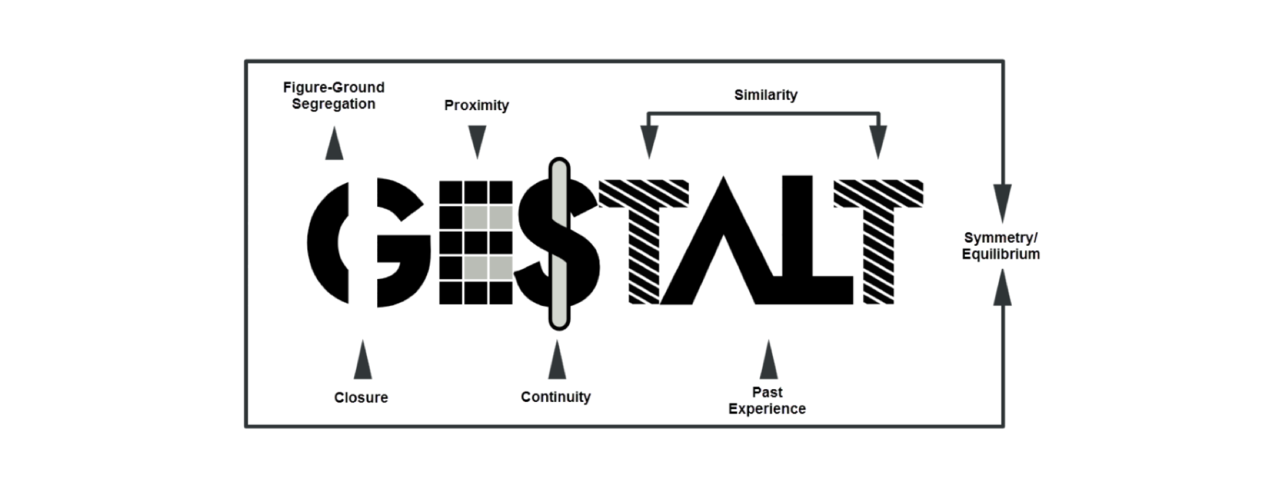

An easy way to remember the feature list is through the Gestalt principles. The Gestalt principles are a set of laws describing how humans typically see objects by grouping similar elements, recognizing patterns and simplifying complex images. The most widely recognized Gestalt Principles are as follows.

Similarity: We seek differences and similarities in size, color, shade, shape and link similar elements.

Proximity: We group closer-together elements, separating them from those farther apart.

Common Region: We group elements that are in the same closed region.

Element Connectedness: We group elements linked by other elements.

Other Gestalt principles of grouping include

Common Fate: We group elements that move in the same direction.

Figure and Ground: The eye differentiates an object form its surrounding area. A form, silhouette, or shape is naturally perceived as figure (object), while the surrounding area is perceived as ground (background).

Meaningfulness (Familiarity): We group elements if they form a meaningful or personally relevant image.

Synchrony: We group static visual elements that appear at the same time.

How can UX designers use these principles?

The Gestalt principles are crucial in UX design as users must be able to understand what they see—and find what they want—at a glance. These principles can be used to guide users to identify elements/objects, draw user’s attention to a particular object and make associations between different objects. Gestalt principles can also be used to avoid confusion and differentiate objects in case of clutter.

Below are few design applications of Gestalt principles:

Example 1: In the before image, it's difficult to identify and differentiate between screen elements. Saturated designs and color noise (background) adds to the clutter making it difficult to focus attention and scan data. By using Gestalt principles, a small tweak can helps achieve clear distinction between screen elements at glance and avoid confusion.

Example 2: Principle of similar size, color and pattern (colored borders) is used to achieve clear distinction between groups.

Example 3: Again, in the before figure, it is difficult to identify and distinguish the login, view video demo, apply, fees & charges and the notice feature. This distinction is achieved using the principle of proximity and common region.

Things to remember when applying Gestalt principles

Designers must understand how that human eye moment flows from one one shape to another. According to an oculometer study, human eye tends to move from:

- Larger objects to smaller

- Irregular objects to regular

- Dark to light shade

- Saturated to unsaturated color

Lastly, designers must remember that while the Gestalt Principles are universal to the human experience, fine-tuning their application demands attention to color use and other cultural considerations.

References

Moore, C. M., & Egeth, H. (1997). Perception without attention: Evidence of grouping under conditions of inattention. Journal of Experimental Psychology-Human Perception and Performance, 23(2), 339-352.

Prinzmetal, W., & Banks, W. P. (1977). Good continuation affects visual detection. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 21(5), 389-395.

Treisman, A. M., & Gelade, G. (1980). A feature-integration theory of attention. Cognitive psychology, 12(1), 97-136.

Treisman, A. (1982). Perceptual grouping and attention in visual search for features and for objects. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 8(2), 194.

Treisman, A., & Gormican, S. (1988). Feature analysis in early vision: Evidence from search asymmetries. Psychological review, 95(1), 15.

Wolfe, J. M., Cave, K. R., & Franzel, S. L. (1989). Guided search: an alternative to the feature integration model for visual search. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human perception and performance, 15(3), 419.

Wolfe, J. M. (1994). Guided search 2.0 a revised model of visual search. Psychonomic bulletin & review, 1(2), 202-238.

Cinematographer based in Mumbai, India.

5yThe same principles are used in Filmmaking by directors :) No surprises there though.