a Ten-Step Guide to CLOSING ARGUMENT

a Ten-Step Guide to CLOSING ARGUMENT

a Ten-Step Guide to CLOSING ARGUMENT

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

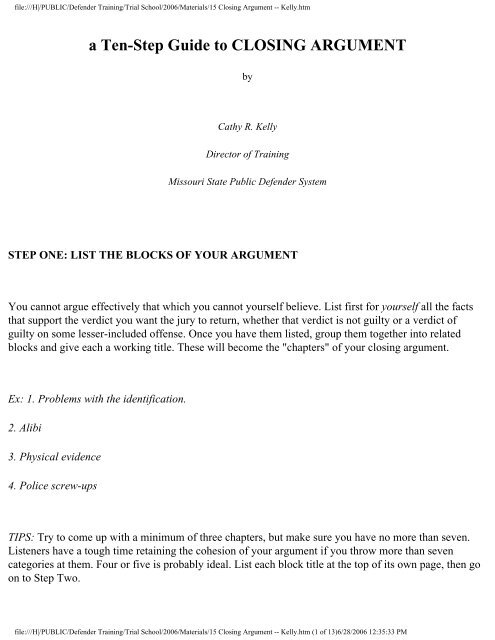

file:///H|/PUBLIC/Defender Training/Trial School/2006/Materials/15 Closing Argument -- Kelly.htma <strong>Ten</strong>-<strong>Step</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>CLOSING</strong> <strong>ARGUMENT</strong>byCathy R. KellyDirec<strong>to</strong>r of TrainingMissouri State Public Defender SystemSTEP ONE: LIST THE BLOCKS OF YOUR <strong>ARGUMENT</strong>You cannot argue effectively that which you cannot yourself believe. List first for yourself all the factsthat support the verdict you want the jury <strong>to</strong> return, whether that verdict is not guilty or a verdict ofguilty on some lesser-included offense. Once you have them listed, group them <strong>to</strong>gether in<strong>to</strong> relatedblocks and give each a working title. These will become the "chapters" of your closing argument.Ex: 1. Problems with the identification.2. Alibi3. Physical evidence4. Police screw-upsTIPS: Try <strong>to</strong> come up with a minimum of three chapters, but make sure you have no more than seven.Listeners have a <strong>to</strong>ugh time retaining the cohesion of your argument if you throw more than sevencategories at them. Four or five is probably ideal. List each block title at the <strong>to</strong>p of its own page, then goon <strong>to</strong> <strong>Step</strong> Two.file:///H|/PUBLIC/Defender Training/Trial School/2006/Materials/15 Closing Argument -- Kelly.htm (1 of 13)6/28/2006 12:35:33 PM

file:///H|/PUBLIC/Defender Training/Trial School/2006/Materials/15 Closing Argument -- Kelly.htmSTEP TWO: LIST BENEATH EACH CHAPTER TITLE EVERYPIECE OF EVIDENCE WHICH SUPPORTS THAT POINT.Scour the discovery in your case -- every police report, lab report, motion hearing transcript, witnessinterview, pho<strong>to</strong>graph, piece of physical evidence, record or fact of any other kind you can get yourhands on. Pull out each piece of evidence which can be used <strong>to</strong> support your theory of the issues and listit beneath the appropriate chapter heading(s).Ex: Problems with the Identification> Only saw man 1 <strong>to</strong> 2 seconds across parking lot> Orig <strong>to</strong>ld police could give no description> 2d time, gave descrip of beige pants> 3rd time, descrip changed <strong>to</strong> bib overallsTIP: You will often encounter one piece of evidence that supports more than one chapter of yourargument. Go ahead and list it under as many chapters as it fits.Caveat: The first time a piece of evidence or a particular witness is mentioned in your argument, thetemptation is <strong>to</strong> launch in<strong>to</strong> a discussion of all the other inferences that can be drawn from that samepiece of evidence or particular witness. "As-long-as-we're-talking-about-so-and-so . . . "DON'T DO IT!Think of it as a play. The issue you are arguing is the scene. The pieces of evidence and the individualwitnesses are the ac<strong>to</strong>rs, brought out <strong>to</strong> say their few lines in support of the issue currently on centerstage and then sent back <strong>to</strong> the wings <strong>to</strong> wait for their next scene. If they have more lines <strong>to</strong> share onother blocks of your argument, call them back out when that block moves on<strong>to</strong> center stage and refer <strong>to</strong>them again. But do not allow them <strong>to</strong> destroy the progress of the show by launching all of their lines forfile:///H|/PUBLIC/Defender Training/Trial School/2006/Materials/15 Closing Argument -- Kelly.htm (2 of 13)6/28/2006 12:35:33 PM

file:///H|/PUBLIC/Defender Training/Trial School/2006/Materials/15 Closing Argument -- Kelly.htmthe entire production the first time they make an appearance!STEP THREE: DEVELOP A COMPLETE <strong>ARGUMENT</strong> WITHIN EACH CHAPTEREvery chapter must have a beginning, a middle, and an end:1. In the beginning, tell your listeners what your point is.In other words, tell them what you're going <strong>to</strong> tell them.2. In the middle, discuss each piece of evidence that supports your point, using <strong>to</strong> your advantage thegood facts and neutralizing as best you can the negative ones.In other words, tell them.3. At the end, repeat the overall point you are trying <strong>to</strong> make, highlighting its connection <strong>to</strong> the verdictyou seek. In other words, tell them not only what you <strong>to</strong>ld them but why you <strong>to</strong>ld them. Don't just set outthe facts and fail <strong>to</strong> articulate the significance of those facts <strong>to</strong> your theory of the case. The close of eachblock of your argument is often an ideal place <strong>to</strong> repeat your case theme if you can make it fit smoothly.PREPARATION TIP:Talk first, write second. None of us talks the same way we write. If you write out your argument first,and then practice speaking it, your end product is much more likely <strong>to</strong> sound stilted and <strong>to</strong> beunpersuasive. Instead, try developing each of your arguments by talking aloud <strong>to</strong> yourself. Make eachpoint of your argument, playing with the phrasing, word choices, points of emphasis, etc. When you'resatisfied with a particular point, then s<strong>to</strong>p and write down whatever notes you need <strong>to</strong> help youremember what you've just developed beyond the next 30 minutes and move on <strong>to</strong> the next point of yourargument.file:///H|/PUBLIC/Defender Training/Trial School/2006/Materials/15 Closing Argument -- Kelly.htm (3 of 13)6/28/2006 12:35:33 PM

file:///H|/PUBLIC/Defender Training/Trial School/2006/Materials/15 Closing Argument -- Kelly.htmCONTENT TIPS:I. Avoid Legal Arguments!Only lawyers are persuaded by legal arguments (and sometimes not even them!) The rest of the world ispersuaded by higher principles than legal loopholes -- things like justice, fairness, right & wrong. If yourcase is built on a legal argument, find a way <strong>to</strong> argue your point without invoking the dry, legaltechnicality itself. Remember those technicalities jurors detest were in fact created <strong>to</strong> protect orimplement those very principles that so appeal <strong>to</strong> their hearts. Find ways <strong>to</strong> tie your argument <strong>to</strong> theprinciple rather than <strong>to</strong> the technicality!Ex: To most jurors, the requirement of proof beyond a reasonable doubt is a legal technicality. The fearof convicting an innocent man is not.II. Consider Your Audience!David Ball, a trial consultant extraordinaire, teaches that you have three audiences during your closingargument and a different mission <strong>to</strong> fulfill with each. Your audiences are:a) Jurors who are already in your favor. Your mission is <strong>to</strong> give them the ammunition with which <strong>to</strong> fightyour battle for you in the jury room.b) Jurors who are undecided. Your mission is <strong>to</strong> persuade them <strong>to</strong> your point of view and likewise givethem the ammunition <strong>to</strong> support it.file:///H|/PUBLIC/Defender Training/Trial School/2006/Materials/15 Closing Argument -- Kelly.htm (4 of 13)6/28/2006 12:35:33 PM

file:///H|/PUBLIC/Defender Training/Trial School/2006/Materials/15 Closing Argument -- Kelly.htmc) Jurors who are already against you. Your mission is <strong>to</strong> avoid entrenching them further and allow themroom <strong>to</strong> both save face and change their minds. (In other words, you don't want <strong>to</strong> say things like "onlyan idiot would believe . . .!")STEP FOUR: DECIDE UPON THE ORDER AND WEED OUT THE CHAFF1. Select the chapter that you believe is your very strongest argument. Place it at the very end of yourclosing.2. Select the chapter that you believe is your second strongest argument. Place it at the beginning of yourclosing.3. Evaluate each chapter of your argument for weak or inconsistent arguments. You will often find thatsome don't really carry their weight. They're throw-away arguments, so throw them away. Less is more.TIP: When selecting the order of your remaining chapters, you want your arguments <strong>to</strong> build upon eachother both logically and emotionally. The emotion of your argument should build throughout <strong>to</strong> a strongending, not wax and wane. 'Tis not a tide we're creating here. If you have a very emotional plea in onechapter and another which is not so emotional, you will generally want <strong>to</strong> put the emotional argument<strong>to</strong>ward the end of your closing and your less emotional chapters <strong>to</strong>ward the front.STEP FIVE: POLISH THE PERSUASIVENESSThere are ways <strong>to</strong> say things and there are ways <strong>to</strong> say things. All is not equal when it comes <strong>to</strong> thepower of the spoken word. Listed below are a number of devices <strong>to</strong> consider when you begin putting<strong>to</strong>gether your argument:file:///H|/PUBLIC/Defender Training/Trial School/2006/Materials/15 Closing Argument -- Kelly.htm (5 of 13)6/28/2006 12:35:33 PM

file:///H|/PUBLIC/Defender Training/Trial School/2006/Materials/15 Closing Argument -- Kelly.htm1. Trilogies -- For reasons known only <strong>to</strong> those folks who study such things, the human mind seems <strong>to</strong>hang on <strong>to</strong> things that come in threes longer than it does <strong>to</strong> things that come solo or in any othercombination. There is something poetic and memorable about trilogies, so look for opportunities <strong>to</strong> buildtrilogies in<strong>to</strong> your argument. Those who doubt the power of the trilogy need only look at those built in<strong>to</strong>their own his<strong>to</strong>ry:Ex: "drugs, sex, and rock & roll""blood, sweat, & tears""red, white, & blue"2. Metaphors - Sentiments, which may be difficult <strong>to</strong> understand when expressed in the abstract, canoften be made much more real and memorable through the use of metaphorical word pictures. Not onlydo such word pictures capture our imagination and, therefore, our memories more than any abstractconcept can, they also appeal <strong>to</strong> our other senses in ways the word alone does not.Ex: "All of his life, he'd been pricked with sharp needles of humiliation."--Robert Pepin3. Alliteration - A series of words that begin with or include the same sound tend <strong>to</strong> be more memorableand more powerful than words with no audi<strong>to</strong>ry connection <strong>to</strong> one another.Ex: "A small-time snitch searching for someone <strong>to</strong> sacrifice.""Close enough for Callahan" (the sloppy investigating officer)" Like most teenagers, she was curious and confused, seduced by and scared of sex."file:///H|/PUBLIC/Defender Training/Trial School/2006/Materials/15 Closing Argument -- Kelly.htm (6 of 13)6/28/2006 12:35:33 PM

file:///H|/PUBLIC/Defender Training/Trial School/2006/Materials/15 Closing Argument -- Kelly.htm4. Quotations -- Not only are quotations a much more succinct and powerful way of making the pointwe want <strong>to</strong> make, they also invoke the imprimatur of the wisdom of the ages upon the actions of yourclient.Ex: Where your client remained at the scene until police arrived, you may want <strong>to</strong> invoke the wisdom ofthe Proverbs: "The wicked flee when no man pursueth, but the righteous stand, bold as a lion.." Or ifyou want <strong>to</strong> highlight how a witness has been caught in his own lies, there is always Sir Walter Scott'swonderful quote, "Oh, what tangled webs we weave when first we practice <strong>to</strong> deceive."TIPS: When using a quotation in your argument, play with placing the emphasis upon different wordswithin the quote <strong>to</strong> vary the meaning and power. In the Proverbs quote above, I had always placed theemphasis on the word "righteous" and was surprised at how much more powerful the quote became formy case simply by shifting the emphasis <strong>to</strong> the action of my client!5. Analogies -- As with metaphors, it is sometimes easier for us <strong>to</strong> understand a situation if we cananalogize it <strong>to</strong> an experience or s<strong>to</strong>ry that is familiar <strong>to</strong> us. This is true for jurors as well. Fairy tales,children's s<strong>to</strong>ries, or everyday experiences can all be valuable <strong>to</strong>ols for analogy in a closing argument.Caveats:(a) Make it succinct. Analogies are no<strong>to</strong>rious for running rampant and swallowing up large chunks ofargument time while your jury fidgets and wishes you would get <strong>to</strong> the point!(b) Only use an analogy if it is unquestionably and directly on point <strong>to</strong> a significant issue of your case.Analogies are <strong>to</strong>o time-consuming <strong>to</strong> waste on an insignificant point; nor do you want <strong>to</strong> get boggeddown in a side battle over whether your analogy fits the point you're trying <strong>to</strong> make. (Such battles can beloud and painful if the prosecu<strong>to</strong>r chooses <strong>to</strong> ram it down your throat during rebuttal, or silent and secretwithin a juror's own mind. Either is deadly <strong>to</strong> your case.)file:///H|/PUBLIC/Defender Training/Trial School/2006/Materials/15 Closing Argument -- Kelly.htm (7 of 13)6/28/2006 12:35:33 PM

file:///H|/PUBLIC/Defender Training/Trial School/2006/Materials/15 Closing Argument -- Kelly.htm6. Silence -- This is an incredibly powerful <strong>to</strong>ol often overlooked by lawyers who are uncomfortablewith it.• Use silence at the beginning of your closing argument <strong>to</strong> build tension in the courtroom and <strong>to</strong> gatherthe attention of your audience. Have you ever been in a noisy classroom where the teacher suddenlys<strong>to</strong>ps talking? You can literally watch the silence move, row by row, all the way <strong>to</strong> the back of the roomuntil every eye is turned <strong>to</strong> the teacher and you could literally hear a pin drop in that room. THAT is alevel of attention you want <strong>to</strong> use your benefit in a courtroom. You get it, easily and instantly, by usingsilence.• Use silence during your argument as a nonverbal parenthesis <strong>to</strong> set apart and emphasize a powerfulpoint or <strong>to</strong> let an argument float in the air for a bit before moving on <strong>to</strong> the next one. Give the jurors timenot only <strong>to</strong> taste but <strong>to</strong> savor your point, before moving <strong>to</strong> the next one.• Use silence at the end of your argument after you have said your last words. Simply stand for amoment, meeting the eyes of each of your jurors, letting your last words soak in before you simply,softly say thank-you and return <strong>to</strong> your seat. All that will happen when you sit down is the prosecu<strong>to</strong>rstarts talking again. That alone is worth postponing. But the silence also again gives the jurors time <strong>to</strong>savor and absorb your argument and <strong>to</strong> note your obvious belief in what you're saying as you solidlystand your ground and meet their eyesDo not clutter it up by moving about! Movement destroys the power of the silence. Learn <strong>to</strong> simplystand and let the silence speak for you on occasion.BUYERS BEWARE: Each of the techniques discussed above is a valuable <strong>to</strong>ol that you need <strong>to</strong> knowhow <strong>to</strong> use. Each can be very powerful if used effectively. As with most good things, however, theymust be used in moderation! Too much of even a good thing can quickly descend in<strong>to</strong> gimmickry andundercut the sincerity of your plea.STEP SIX: CREATE CHAPTER HEADINGS & TRANSITIONSfile:///H|/PUBLIC/Defender Training/Trial School/2006/Materials/15 Closing Argument -- Kelly.htm (8 of 13)6/28/2006 12:35:33 PM

file:///H|/PUBLIC/Defender Training/Trial School/2006/Materials/15 Closing Argument -- Kelly.htmEver try <strong>to</strong> read a book of several hundred pages with no chapters? Probably not. There is a reason forthat. Without some framework for processing it all, the reader gets information overload and just givesup. The same is true for closing arguments. You have lived and breathed this case for days, weeks, andmonths by the time of closing. You can jump back and forth between issues & <strong>to</strong>pics & players withou<strong>to</strong>nce losing the action. Jurors don't have that luxury. This is their one and only time through. It is mucheasier for them <strong>to</strong> get lost than you realize! And if you lose them? You lose.1. Chapter Headings:Always give your jurors a "heads-up" that you are moving <strong>to</strong> a new <strong>to</strong>pic. This can be as simple as a"Now let's talk about the sloppy police work brought <strong>to</strong> you in this case." Or you may want <strong>to</strong> use a flipchart <strong>to</strong> list "the five things you heard in this case that show us the police have the wrong man," thensimply flip the page <strong>to</strong> the next chapter of your argument when you're ready <strong>to</strong> move on. Anotherexcellent method of chapter headings is <strong>to</strong> simply ask the questions you know the jury wants answered.Ex. In a rape case where the defense is consent but all parties agree the victim was found in tears, If thisis what she wanted, if this were her choice, then why was she crying? Then answer the question! Thereare any number of ways <strong>to</strong> communicate your chapter headings <strong>to</strong> your jurors and by all means drawupon your own creativity in the process. Just make sure you DO it.2. Transitions Between ChaptersEven with a chapter heading, shifts of <strong>to</strong>pic can be jarring if they are <strong>to</strong>o abrupt or seem whollyunrelated or unconnected in any way <strong>to</strong> what has gone before. It's as if you're speeding down a street andsuddenly slam on your brakes <strong>to</strong> make a sharp, right turn. Your passengers may be dragged along withyou, but if they didn't know it was coming they may take a few minutes <strong>to</strong> catch their breath again. Youcannot afford for your jurors <strong>to</strong> spend a few minutes "catching up" <strong>to</strong> you during your closing argument.After all, you only have a few minutes! How <strong>to</strong> avoid it?Make sure you slow down before you reach the turn:a) Give each chapter of your argument a clear and definite closure;file:///H|/PUBLIC/Defender Training/Trial School/2006/Materials/15 Closing Argument -- Kelly.htm (9 of 13)6/28/2006 12:35:33 PM

file:///H|/PUBLIC/Defender Training/Trial School/2006/Materials/15 Closing Argument -- Kelly.htmb) Pause;c) Announce your next chapter heading; (ask your question, flip your chart, etc.)d) Pause briefly again <strong>to</strong> give your jurors time <strong>to</strong> make that move with you, then begin.TIP: One excellent transition technique is <strong>to</strong> tie each of your chapters back <strong>to</strong> your theme. Not only doesthis give you added opportunity <strong>to</strong> repeat your theme, it also helps jurors understand that the variouschapters of your closing are simply different branches of the same tree.Ex: [Closing of Chapter One] The victim's description does not match Joe Defendant because the policehave the wrong man.[Heading of Chapter Two] What's the second piece of evidence you heard from that stand that shows thepolice have the wrong man?And then launch in<strong>to</strong> your second chapter.step seven: DECIDE YOUR OPENING HOOKthe first few moments of your closing is the most attentive your jury will be throughout your argument.Do not waste it with thank-you's or apologies for how long the trial has taken. Start with somethingstrong and attention-grabbing that will make your jurors want <strong>to</strong> stay with you beyond your openinglines!file:///H|/PUBLIC/Defender Training/Trial School/2006/Materials/15 Closing Argument -- Kelly.htm (10 of 13)6/28/2006 12:35:33 PM

file:///H|/PUBLIC/Defender Training/Trial School/2006/Materials/15 Closing Argument -- Kelly.htmSTEP EIGHT: DECIDE ON YOUR <strong>CLOSING</strong> LINES:All <strong>to</strong>o often you will see an otherwise great closing argument trickle off in<strong>to</strong> a mumbled thanks at theend, draining the power of the defense away with it. Don't leave your closing lines <strong>to</strong> chance! You want<strong>to</strong> take that opportunity <strong>to</strong> ask the jury for the verdict you want, but there are thousands of ways <strong>to</strong> dojust that. The goal is <strong>to</strong> find a way that is powerful, persuasive, and that comes from your heart.STEP NINE: Practice itYou must prepare not only the content of the closing, but the delivery, and that can only be done throughpractice. Practice it aloud -- <strong>to</strong> yourself, <strong>to</strong> your mirror, <strong>to</strong> your spouse, colleague or pets -- but practiceit.Do not memorize it. Few of us are sufficiently gifted thespians <strong>to</strong> deliver a memorized monologue andmake it ring sincere. Simply talk it through several times. Each time you do, your argument will comeout slightly different and that is the way it should be. That's what keeps it fresh and sincere and real.What you want <strong>to</strong> remember are those key phrases you've chosen, the metaphors, analogy, or trilogies;the silences you've built in; the transitions you've decided upon-- as well as, of course what evidence youwant <strong>to</strong> discuss under each chapter!STEP TEN: reduce it <strong>to</strong> outline formYou cannot read a closing argument and persuade anyone of anything. Your persuasiveness comes fromyour own passion about that of which you speak. If you don't know it well enough <strong>to</strong> remember itwithout reading it, you've just spoken volumes <strong>to</strong> the jury about just how passionately you feel about it!"But there is SO much <strong>to</strong> remember!!" Yes, there is. That's why you must PRACTICE, PRACTICE,file:///H|/PUBLIC/Defender Training/Trial School/2006/Materials/15 Closing Argument -- Kelly.htm (11 of 13)6/28/2006 12:35:33 PM

file:///H|/PUBLIC/Defender Training/Trial School/2006/Materials/15 Closing Argument -- Kelly.htmPRACTICE until you know your arguments so well that you can speak from the heart about each andevery one of them.Then reduce your argument <strong>to</strong> a one-page outline form which you can lay on the lecturn or table corneras your safety net in case you go blank. The outline will list your chapter headings and no more than aword or two prompt for each of the pieces of evidence you plan <strong>to</strong> discuss under that heading.Ex: I. ID Probs> 1-2 secs> distance> descriptionsIf your notes are any more detailed than this, you will not be able <strong>to</strong> even find your place in a glance,much less your prompt; and a glance is all you can spare for notes during closing!!TIPS: Place your cup of water beside your outline during your closing. Then if you DO go blank andhave <strong>to</strong> refer <strong>to</strong> them, you can simply pause, walk <strong>to</strong> your cup, take a sip (while you're franticallyscanning your outline) and as far as the jury knows, you simply had a dry throat.Or you can list your chapters and supporting evidence on a flip chart for use as demonstrative evidenceduring your closing argument. Not only does this allow the jury <strong>to</strong> follow your argument more easily asyou go through each <strong>to</strong>pic, you don't have <strong>to</strong> worry about using your notes!________________________________A Word About S<strong>to</strong>rytelling:file:///H|/PUBLIC/Defender Training/Trial School/2006/Materials/15 Closing Argument -- Kelly.htm (12 of 13)6/28/2006 12:35:33 PM

file:///H|/PUBLIC/Defender Training/Trial School/2006/Materials/15 Closing Argument -- Kelly.htmThe new <strong>to</strong>uchs<strong>to</strong>ne in trial practice is s<strong>to</strong>rytelling and I am one of its avid disciples. However, I amconvinced that the best s<strong>to</strong>ryteller will fail <strong>to</strong> persuade the jury if s/he uses closing argument only as anopportunity <strong>to</strong> tell a s<strong>to</strong>ry. A s<strong>to</strong>ry <strong>to</strong>ld well may hold the jurors' interest and even entertain them, but ifthe lawyer fails <strong>to</strong> explain why it matters <strong>to</strong> their verdict, in the end, the lawyer will still lose. For thatreason, I encourage you <strong>to</strong> think of a good closing argument not as a single s<strong>to</strong>ry, but as a wellorganizedpho<strong>to</strong> album; each page of vivid, vibrant pho<strong>to</strong>graphs carefully attached in its appropriateplace beside a succinct, running commentary. The commentary points out the significance of andsubtleties within each pho<strong>to</strong>graph that might easily be missed or overlooked by the casual observer.The pho<strong>to</strong>graphs in your closing argument are the vignettes and scenes carefully culled from theevidence and vividly painted for your jurors through the skills of s<strong>to</strong>rytelling <strong>to</strong> prove a point. Themoment your innocent client learns he's falsely accused and yet does not run away is a pho<strong>to</strong>graph thatsupports his innocence. The harsh reality of an interrogation room is a pho<strong>to</strong>graph which explains whythe confession does not match the physical evidence and is therefore not believable. Each of these scenesmust be brought <strong>to</strong> life again for the jurors during your argument through the skill of s<strong>to</strong>rytelling. Yetthey do not and cannot stand alone. Without benefit of an accompanying commentary, a carefullycraftedexplanation of how each of these events fit <strong>to</strong>gether <strong>to</strong> paint a picture of innocence, you run thevery real risk that your jurors may never understand the significance of or subtleties within yourpho<strong>to</strong>graphs. Absent that understanding, the likelihood they will reach the conclusion you want them <strong>to</strong>reach is a risk no gambler would want <strong>to</strong> take.Of course, the opposite extreme is equally ineffective. The perusers of our proverbial pho<strong>to</strong> album willquickly lose interest in the most thorough of commentaries if there are no pho<strong>to</strong>graphs <strong>to</strong> accompany it!A dry exposition on how the evidence supports a finding of not guilty does not move us, capture ourattention or imagination, or make us care. BOTH vivid pho<strong>to</strong>graphs (s<strong>to</strong>rytelling) and carefully craftedcommentary (argument) are critical <strong>to</strong> an effective closing. Equal attention must be paid <strong>to</strong> both.file:///H|/PUBLIC/Defender Training/Trial School/2006/Materials/15 Closing Argument -- Kelly.htm (13 of 13)6/28/2006 12:35:33 PM