The Difference between an Absolute and a Limited Monarchy

The Difference between an Absolute and a Limited Monarchy

The Difference between an Absolute and a Limited Monarchy

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

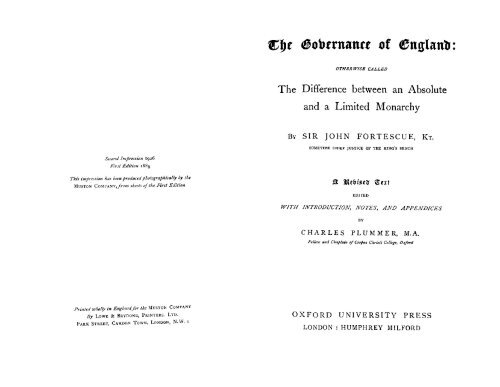

OTHER WISE CALLED<strong>The</strong> <strong>Difference</strong> <strong>between</strong> <strong>an</strong> <strong>Absolute</strong><strong>an</strong>d a <strong>Limited</strong> <strong>Monarchy</strong>BY SIR JOHN FORTESCUE, KT.SOMETIME CHIEF JUSTICE OF THE KING'S BENCHSecond Impression 1ga6First Edition I 885This inrpression has been produced photographically by theRlusro~ COYP.~NY,~YO~Z sheefs of the First EditionEDI I'EDWITH INTRODUCT/ON, NOTES, AND APPENDICESBYCHARLES PLURIMER, M.A.Fellow <strong>an</strong>d Cha#hi~z of Cows Clrrisfi College, OxfordPyi~zled ZU~OL)IY in EngZaud for the MUSTON COMPANYBy LOWE & BRY~ONE, PRINTERS. LTD.PARK STREET. CAMDRN TOWN, LONDON, N.W. IOXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESSLONDON : HUMPHREY MILFORD

PAGEvxiii'<strong>The</strong> idea of a polity in which there is the same law for all, a polity administeredwith regard to equal rights <strong>an</strong>d equal freedom of speech, <strong>an</strong>d theidea of a kingly government which respects most of all the liberty of thego5erned.'-LONG'S TRANSLATION.INTRODUCTION :Part I. Constitutional Sketch of the L<strong>an</strong>castri<strong>an</strong> <strong>an</strong>d YorkistPerlod (1399-1483). . . . . .Part 11. Life of Sir John Fortescue . . . . .Part 111. Writings, Opinions, <strong>an</strong>d Character of Sir John Fortescue. . . . . . . .SIR JOHN FORTESCUE ON THE GOVERNANCE OF ENGLAND .APPENDIX A. 'Example what Good Counseill helpith <strong>an</strong>dav<strong>an</strong>tageth, <strong>an</strong>d of the contrare whatfolowith. Secundum Sr. J. Ffortescu,Knighte ' . . . . . . .APPENDIX B. 'Articles sente fro the Prince, to therle ofWarrewic his fadir-in-lawe '. . .APPENDIX C. ' <strong>The</strong> Replication agenst the clayme <strong>an</strong>d titleoftheDucoffYorke'. . . . .APPENDIX D. Fragment of the treatise 'On the Title of theHouseofYork'. . . . . .

THE work here presented to the reader has been threetimes previously printed ; twice, in 1714 <strong>an</strong>d 1719 by Mr..afterwards Sir John, Fortescue-Al<strong>an</strong>d, who ultimatelybecame Lord Fortescue of Cred<strong>an</strong>, <strong>an</strong>d once by LordClermont in his edition of the collected works of Fortescuel.Of these editions the two first havc become very scarce.while the third is only printed for private circulation. Ofall three the value is very much impaired by the fact thatthe text is based on a comparatively late m<strong>an</strong>uscript;while no attempt has ever been made to bring out tliehistorical signific<strong>an</strong>ce <strong>an</strong>d relations of the treatise. It ishoped therefore that the appear<strong>an</strong>ce of the presentedition, which aims at supplying these deficiencies, will notbe considered to be without justification.Had the treatise ' On the Govern<strong>an</strong>ce of Engl<strong>an</strong>d ' noother claims on our attention, it would deserve considerationas the earliest treatise on the English Constitution writtenin the English l<strong>an</strong>guage. Rut as a matter of fact, itshistorical interest is very high indecd ; far higher, I ventureto think, th<strong>an</strong> that of the author's better-known Latintreatise De Lalm7i6us Leg-~~g~t AfgZia. We here see thatFrom two notices in Heame's Collections (ed. Doble, i. 46, 154) it woilldthat Lord Fortescue of Cred<strong>an</strong> at one time entertained the idea, ultlmatel~carried out by Lord Clermont, of printing a collected edition of theworks of their <strong>an</strong>cestor.

iiipreface.Fortescue, while remaining true to those liberal principlesof government which he had previously enunciated, was yetIceenly sensible of the evils of L<strong>an</strong>castri<strong>an</strong> rule, <strong>an</strong>d that inthe various remedies suggested by him, which have fortheir object the strengthening of the powers of the Crown<strong>an</strong>d the reduction of the influence of the nobles, he was,consciously or unconsciously, helping to prepare the wayfor the New <strong>Monarchy</strong>.This connexion of the work with the history of the timeI have endeavoured to draw out, by bringing together fromcontemporary authorities whatever seemcd to illustrate theme<strong>an</strong>ing of the author. <strong>The</strong> closeness of the connexion isshown by the fact, more th<strong>an</strong> once pointed out in the notesto the present edition, that the l<strong>an</strong>guage of Fortescue isoften identical with that of the public documents of theperiod. And this in turn illustrates <strong>an</strong>other point of someimport<strong>an</strong>ce to which I have also drawn attention ; the factnamely that Fortescue, first of medixval political philosophers,based his reasonings mainly on observation of existingconstitutions, instead of merely copying or commentingon Aristotle.It follows from this that the inspiration which Fortescuederived from literary sources is subordinate in import<strong>an</strong>ceto that which he drew from the practical lessons of history<strong>an</strong>d politics. But I have endeavoured to illustrate thispoint also. <strong>The</strong> four works of which Fortescue seems tohave made most use are : the De Regignine Przlzcipunzwhich goes under the name of St. Thomas Aquinas, thoughonly a portion of it is by him; the treatise with the sametitle by Agidius Rom<strong>an</strong>us; the De Morali PyincipumInstitutione of Vincent of Beauvais ; <strong>an</strong>d the Cowi$~ndizigriMorale of Roger of Waltham. <strong>The</strong> first two works havebeen often printed, <strong>an</strong>d are more or less well known; thetwo last exist only in m<strong>an</strong>uscript. It has added interest tomy study of Vincent of Beauvais' treatise that I have beenable tc. read it in the very m<strong>an</strong>uscript used by Fortescuehimself. <strong>The</strong> Comn$e?zdiz~nt Morale of Roger of WalthamI think I may almost claim to have discovered ; for thoughit is mentioned by Lel<strong>an</strong>d <strong>an</strong>d his copyists, it is clear thatthey c<strong>an</strong>not have had much acquaint<strong>an</strong>ce with its contents,they would not have fixed the author's j'orz~it asthey have done. Of Aristotle, except so far as Aristoteli<strong>an</strong>doctrines are embodied in the above-named works, Ihave shown that Fortescue knew nothing beyond thecollection of quotations which goes by the name of theAuctoritntes Avistotclis.One of the most import<strong>an</strong>t sources from which <strong>an</strong> authorc<strong>an</strong> be illustrated is himself. From this point of view I amunder the greatest obligations to the collection of Fortescue'sWorks printed-I wish I could have added, published-by his descend<strong>an</strong>t, Lord Clermont. It is I trust in nocaptious spirit that I have occasionally pointed out what seemto me omissions <strong>an</strong>d mistakes on the part of the noble editor.If all representatives of historic houses would imitate theexample set by Lord Clermont, light would be thrown onm<strong>an</strong>y a dark corner of English history. I have also derivedmuch assist<strong>an</strong>ce from the scholarly notes on Fortescue'slongest work, the ?De Natu~d Lcgis Arnture, with whichLord Carlingford, then Mr. Chichester Fortescue, enrichedhis brother's edition of that treatise.In regard to the Appendices, the first <strong>an</strong>d third aremerely reprints from older <strong>an</strong>d completer MSS. of documentsalready given by Lord Clermont ; the second <strong>an</strong>dfourth are new, though I have given reasons for believingthat the last is a fragment of a treatise of which otherhave been printed by Lord Clermont. Fromthe second a brief extract was printed by Sir Henryin his Historical Letters, though without recognisingeither its author or its import<strong>an</strong>ce. It is however, as Ihave shown, closely connected with the present work, theb

preface. preface, xihistorical bearing <strong>an</strong>d signific<strong>an</strong>ce of which it illustrates in avery striking m<strong>an</strong>ner.In reference to the life <strong>an</strong>d times of Fortescue I havebeen able to gle<strong>an</strong> some facts which have escaped previousbiographers. <strong>The</strong>se are derived chiefly from French <strong>an</strong>dBurgundi<strong>an</strong> sources. I c<strong>an</strong>not help thinking that the valueof these authorities for English history, though long agopointed out by Mr. Kirk in his History of Charles the Bold,has hardly been sufficiently appreciated by English histori<strong>an</strong>s; while if the archives of Fr<strong>an</strong>ce contain m<strong>an</strong>y moredocuments bearing on English history equal in import<strong>an</strong>ceto those printed by Mdlle. Dupont in her edition of Waurin<strong>an</strong>d by M. Quicherat in his edition oi Basin (both publishedunder the auspices of the Socidti: de 1'Histoire de Fr<strong>an</strong>ce),much light may be hoped for from that quarter. A visit tothe Record Office enabled me to clear up some mistakes <strong>an</strong>dobscurities in regard to Fortescue's l<strong>an</strong>ded property.It will be seen that I have edited this work from a historical<strong>an</strong>d not from a philological point of view. Of the MSS.employed in the formation of the text a sufficient accountwill be found in the Introduction. A few words may herebe said as to the m<strong>an</strong>ner in which I have dealt with them.I have, I believe, noted all cases in which I have departedfrom the reading of the MS. on which I have based mytext. In other inst<strong>an</strong>ces I have only given such variousreadings as seemed to me to have some historical or philologicalinterest, or to be of import<strong>an</strong>ce as illustrating therelations of the MSS. to one <strong>an</strong>other. For9ns of wordswhich appeared to me worthy of notice I have frequentlyincluded in the Glossary, with <strong>an</strong> indication of the MS.from which they are taken. Stops <strong>an</strong>d capitals are intro-duced in conformity with modern usage; quotations havebeen indicated, as in MS. Y, by the use of Gothic letters.I have not attempted to distinguish <strong>between</strong> Early English) <strong>an</strong>d Middle-English y, as they are sometimes called ;they are used promiscuously, they fade imperceptibly into<strong>an</strong>d after all the y is only badly written.1 have printed P throughout. In regard to the junction<strong>an</strong>d of words the MS. has been closely followed.<strong>The</strong> only exception is in the case of the indefinite article aor <strong>an</strong>, which in the MS. is sometimes joined with <strong>an</strong>d sometimesseparated from the word to which it belongs ; I havealways separated it. In the case of words just hovering onthe verge of becoming compounds, <strong>an</strong>d neither completelyjoined nor completely separated in the MS., I have followedthe example of Professor Earle <strong>an</strong>d divided the elements bya half-space, objecting with him to-the use of hyphens asa purely modern invention. In the MS. the worcr n?zd issometimes abbreviated, sometimes written in full ; it ishere always printed in full. With these exceptions thepeculiarities of the MS. followed are, I believe, faithfullyreproduced, extended contractions being marked in theusual way by italics.<strong>The</strong> Glossarial Index is merely intended to give help tothose who, reading the text for historical purposes, may bepuzzled by Middle-English forms or me<strong>an</strong>ings. It makesno pretensions to <strong>an</strong>y philological value.I trust that this work may prove useful both to teachers<strong>an</strong>d students of history in Oxford <strong>an</strong>d elsewhere. But mymain object has been to illustrate my author, <strong>an</strong>d that isthe point of view from which I would desire to be judged.In a body of notes r<strong>an</strong>ging over so m<strong>an</strong>y subjects, someof them lying far outside the sphere of my ordinary studies,it is possible that there should not be slips <strong>an</strong>dFor the correction of these, whether publiclyOr privately, I shall always be grateful ; <strong>an</strong>d I should wishas my own the words of one of the most unselfishlabourers in the field of learning, Herm<strong>an</strong>n Ebel : opprobretnobis, qui volet, mod0 corrigat.'Itfor me to pay the tribute of my heartyb 2

th<strong>an</strong>ks in the m<strong>an</strong>y quarters where that tribute is due.I have to th<strong>an</strong>k the Delegates of the Clarendon Press forthe generous confidence with which they accepted the workof <strong>an</strong> untried h<strong>an</strong>d, <strong>an</strong>d for the liberality with which theypermitted <strong>an</strong> extension of its scope much beyond what wasoriginally contemplated. To the Lord Bishop of Chester Iam under special obligations ; who not only encouragedme to undertake the work, but both as a Delegate of thePress <strong>an</strong>d in his private capacity heIped it forward at a greatexpenditure of trouble to himself; to his published writingsI, in common with all students of history, owe a debt ofgratitude which c<strong>an</strong> never be adequately expressed. To theRev. C. W. Boase, Fellow of Exeter College, I am indebtedfor const<strong>an</strong>t encouragement <strong>an</strong>d assist<strong>an</strong>ce ; nor am I the firstwho has profited by his wealth of historical learning ; whileProfessor Skeat gave me much kind help <strong>an</strong>d advice withreference to points of philology. Mr. Edward Edwards.the well-known <strong>an</strong>d accomplished author of the Life ofRalegh, took more trouble th<strong>an</strong> I like to think of, in theendeavour to clear up some points in which I was interested.That his researches were not always crowned with successdoes not diminish my sense of gratitude. <strong>The</strong> help whichI have received in regard to special points is acknowledgedin the book itself. I am indebted to Lord Calthorpe forthe facilities which he afforded me in consulting the YelvertonMS., to Mr. Henry Rradshaw for similar favours inregard to the Cambridge MS., <strong>an</strong>d to the Master <strong>an</strong>dFellows of Trinity College, Cambridge, for the lo<strong>an</strong> of theirMS. containing the Epitome; while to the Provost <strong>an</strong>dFellows of Queen's College, Oxford, my th<strong>an</strong>ks are due forallowing me even a larger use of their valuable library th<strong>an</strong>that which they so liberally accord to all Graduates. Ihave to th<strong>an</strong>k Mr. W. D. Selby, who directed my researchesat the Record Office ; <strong>an</strong>d Mr. E. J. L. Scott, of the Departmentof MSS., who did me the like service at the Britishg%eface,Museum. At the Bodlei<strong>an</strong> I received const<strong>an</strong>t help fromMr. Mad<strong>an</strong> the Sub-Librari<strong>an</strong>, while Mr. Macray was <strong>an</strong>unfailing oracle on all points of palaography. I shouldlike also to th<strong>an</strong>k generally the officials of all the threeinstitutions which I have named, for their unfailing courtesy,<strong>an</strong>d helpfulness. To the m<strong>an</strong>y friends who havehelped me, if indirectly, yet very really by their sympathy<strong>an</strong>d the interest they have taken in my work, I would alsohere return my grateful th<strong>an</strong>ks. To one of them this workwould probably have been dedicated, were it not thatdedications are said to be somewhat out of date in thisenlightened age.C. C. C., OXON.,]U& 29, 1885.xiii

NOTE.-AS a general rule the authorities referred to will be easilyidentified ; only those are given here as to which <strong>an</strong>y doubt might belikely to arise.-[C. S. = Camden Society. R. S. = Rolls Series.]ERRATA.p. 41, 1. 13, for Chief Justice of Engl<strong>an</strong>d, rcad Chief Justice of the King'sBench.p 64, note 5; p. 65, note z ; p. 215, 1. 13 from bottom, for Ormond, rtadOrmonde.p. 81, 1. zz, for trace, readtract.p. 84,l. 10, for 1464, read 1463.p. 249, 1. 6 from bottom,for de, read le.p. 263,l. 7 from bottom,for sports, read spots.p. 349, margin, insert his after Warrewic.Xgidius Rom<strong>an</strong>us, De Regivzi~ie Pri?zcz$wn. English tr<strong>an</strong>slation inMS. Digby 233.Ulakm<strong>an</strong>, in Hearne's Otterbourne.Burton, History of Scotl<strong>an</strong>d. Cabinet edition.Chastellain, ed. Kervyn de Lettenhove.Continuator of Croyl<strong>an</strong>d, in Fulm<strong>an</strong>'s Scriptores Veteres, vol. i.fol. 1684.De Coussy, ed. Buchon.English Chronicle, ed. Davies. C. S.Faby<strong>an</strong>, ed. Ellis, $0.Fortescue's Works, etc., ed. Clermont.<strong>The</strong> writings of Fortescue occupy the first volume of a work in twovolumes by Lord Clermont, with the title 'Sir John Forteshe <strong>an</strong>dhis Descend<strong>an</strong>ts ;' the Family History forming the second volume.<strong>The</strong> latter was however subsequently reprinted as a subst<strong>an</strong>tivework, <strong>an</strong>d it is always this second edition which is cited under thetitle ' Family History.' <strong>The</strong> Legal Judgements of Sir John Fortescuewill be found at the end of his Works, with a separatepagination. Of his works, the De Naturd Legis Nature is citedfor shortness as N. L. N., the L Govern<strong>an</strong>ce of Engl<strong>an</strong>d ' as theMonarchia.Froude, History of Engl<strong>an</strong>d. Cabinet Edition.Grego~'s Chronicle, in Gairdner's ' Collections of a London Citizen.'C. S.Chronicle, 4to., ed. 1809.

xviai$t of autboritiea.Hallam, Constitutional History. Library Edition, 1854.,, Literature of Europe. Cabinet Edition.,, Middle Ages. Cabinet Edition, 1872.Hardyng, ed. Ellis. 4to.Hearne's Fragment, in Hearne's ' Sprotti Chronica.'Household, Ordin<strong>an</strong>ces of the Royal, published by the Society ofAntiquaries. (Cited as ' Ordin<strong>an</strong>ces, &C.')ivlartineau, History of the Peace. 4 vols. 8vo., 1877-8.Monstrelet. 3 vols. fol., 1595.Paston Letters, ed. Gairdner.Political Songs, ed. Wright. C. S.99 9) R. S.Proceedings <strong>an</strong>d Ordin<strong>an</strong>ces of the Privy Council, ed. Sir HarrisNicolas. (Cited as P. P. C.)Pseudo-Aquinas. Under this title is cited that part of the De RegiminePrincz~unz which is not by St. Thomas Aquinas.Rede's Chronicle, in MS. Rawl. C. 398.Rymer's Fcedera. Original Edition, 1704-1735.Stowe's Annals, ed. 1631, fol.Stubbs' Constitutional History. Cabinet Edition.(Cited as S. C. H,)Turner, Sharon, History of Engl<strong>an</strong>d during the Middle Ages. 8vo.Edition.Vincent of Beauvais, De MoraLiPrincifizr7lt Institzrtione, in MS. Raw].C. 398.\iTaltham, Roger of, Co~~ipendii~~i~ Morale, in hIS. Laud. hlisc. 616.Wars of8 the English in Fr<strong>an</strong>ce, Letters <strong>an</strong>d Papers illustrative of the,ed. Stevenson. K. S. (Cited as ' English in Fr<strong>an</strong>ce.')Waurin, Anchiennes Chroniques, ed. Mdlle. Dupont. (Societ.6 de1'Histoire de Fr<strong>an</strong>ce.)\Vhethamstede. R.S.Worcester, Willialn, Collections, <strong>an</strong>d i\nnals, in Wars of the Englishin Fr<strong>an</strong>ce, q. v.atbronoiogical Cable of tbe Life, Cimes, <strong>an</strong>o? 1390-1400, Birth of Fortescue.1399. Oct. Accession of Henry IV.1413. &farch. Accession of Henry V.1422. Sept. Accession of Henry VI.1425, 1426, <strong>an</strong>d 1429. Fortescue Governor of Lincoln's Inn.1429 or 1430. Fortescue becomes a Serge<strong>an</strong>t-at-Law.1429. NOV. 6. Coronation of Henry V1 at Westminster.1431. Dec. 17. 9, ,, at Paris.1435. Aug. Conference of Arras.? 143 j-6. Fortescue marries Elizabeth or Isabella Jamyss.1435-6. Fortescue acquires l<strong>an</strong>ds in Devonshire by gr<strong>an</strong>t of hisbrother Henry.1439. Conference of Calais.1440. Jzmc. Gloucester's m<strong>an</strong>ifesto on the release of the Duke ofOrle<strong>an</strong>s.1440 <strong>an</strong>d 1441. Fortescue acts as Judge of Assize on the Norfolkcircuit.I44I. Easter Temt. Fortescue made a King's Serge<strong>an</strong>t.- Gr<strong>an</strong>t to Fortescue <strong>an</strong>d his wife of l<strong>an</strong>ds at Philip's Norton.'44% /a?t.Fortescue made Chief Justice of the King's Bench.Feb. Gr<strong>an</strong>t to Fortescue of a tun of wine <strong>an</strong>nually.Oct. Fortescue -ordered to certify the Council as to certainindictments brought against the Abbot of Tower Hill.FOrtescue ordered to commit to bail certain adherents of SirWilliam Boneville.Or I443. Fortescue knighted.

xviii CLbconological Cable, QLbronologicaI Cable, six1443. J<strong>an</strong>. or Feb. Fortescue sent on a special commission intoNorfolk.1March 4. Letter of th<strong>an</strong>ks from the Council to Fortescue.- 14. Fortescue ordered to send to the Council a list ofpersons eligible for the offices of J.P. <strong>an</strong>d Sheriff inNorfolk.23. Fortescue makes his report to the Council on theaffairs of Norfolk.April3 <strong>an</strong>d May 3. Fortescue attends the Privy Council.May 8. Warr<strong>an</strong>t ordered for the payment of 50 marks toFortescue.May 10. Fortescue summoned to advise the Council withreference to the attacks on Cardinal Kemp's estates.- I I. Fortescue makes his report to the Council.- 18. Fortescue sent on a special commission into Yorkshire.May. Gr<strong>an</strong>t to Fortescue of a tun of wine <strong>an</strong>nually.Ju& 11. Fortescue attends the Privy Council.Confirmation to Fortescue <strong>an</strong>d his wife of the l<strong>an</strong>ds at Philip'sNorton.1444. J<strong>an</strong>. Fortescue ill of sciatica, <strong>an</strong>d unable to go on circuit.1445. Feb.-1455. /U&. Fortescue a trier of petitions in Parliament.r445. April 22. Marriage of Henry V1 with Margaret of Anjou.1447. Feb. 23. Death of Gloucester.March. Fortescue receives <strong>an</strong> addition ofA4o to his salary.April I I. Death of Cardinal Beaufort.Oct. Fortescue <strong>an</strong>d his wife receive letters of confraternityfrom Christ Church, C<strong>an</strong>terbury.Fortescue refuses to deliver Thomas Kerver out of WallingfordCastle.I 447-8 Fortescue arbitrates <strong>between</strong> the Chapter <strong>an</strong>d Corporationof Exeter.lqjo. ja/~.-~lFarch. Fortescue acts as spokesm<strong>an</strong> of the Judges inrelation to the trial of Suffolk.May. Murder of Suffolk. Rising of Cade.Aug. Fortescue sent on a special commission into Kent.Sejnf. <strong>The</strong> Duke of York comes over from Irel<strong>an</strong>d.1451. May-June. Fortescue expecting to be attacked in his house.,452. Oct. Fortescue acquires the m<strong>an</strong>or of Geddynghall, <strong>an</strong>d otherl<strong>an</strong>ds in Suffolk.1~53. ]U& 6. <strong>The</strong> King falls ill at Clarendon.Oct. 13. Birth of Prince Edward of L<strong>an</strong>caster.1454. Feb. Fortescue delivers the opinion of the Judges on the caseof Thorpe.March 22. Death of Kemp.Apn'l 3. York appointed Protector.June g. Edward of L<strong>an</strong>caster created Prince of Wales.Dec. 25. Recovery of the King.Fortescue divests himself of his l<strong>an</strong>ds in Devonshire in favourof his son Martin.1455. May 22. First battle of St. Alb<strong>an</strong>'s. Death of Fortescue'syounger brother, Sir Richard Fortescue.Oct. <strong>The</strong> King falls ill again at Hertford.Nov. rg. York reappointed Protector.1456. Feb. <strong>The</strong> King recovers.Feb. 25. York dismissed from the Protectorship.Feb. Fortescue arbitrates <strong>between</strong> Sir John Fastolf <strong>an</strong>d SirPhilip Wentworth.March. Fortescue consulted by the Council with reference tothe Sheriffdom of Lincolnshire.May. Fortescue sits on a special commission at the Guildhall.Fortescue acquires the reversion of the m<strong>an</strong>or of Ebrington.1457. May. Fortescue acquires l<strong>an</strong>ds at Holbeton, Devon.'458. March 25. Peace made <strong>between</strong> the L<strong>an</strong>castri<strong>an</strong>s <strong>an</strong>d I'orkists.Margaret of Anjou instigates Charles V11 to send French troopsto Engl<strong>an</strong>d.'459 Sept. 23. Battle of Bloreheath.Oct. 12. Dispersal of the Yorkists at Ludlow.Nov. Parliament of Coventry. Activity of Fortescue.Dec. 7. Attainder of the Yorkists.Foftescue appointed a feoffee for executing the King's will.'4". Feb. Negotiations of Margaret of Anjou with Fr<strong>an</strong>ce.Jub 10. Battle of Northampton.Oct. <strong>The</strong> Duke of York claims the crown.

Oct. Margaret <strong>an</strong>d the Prince in Wales.Dec. 31. Battle of Wakefield.1461. ]<strong>an</strong>.Negotiations of Margaret <strong>an</strong>d the Dowager Queen ofScotl<strong>an</strong>d at Lincluden.J<strong>an</strong>. 20. Bond of L<strong>an</strong>castri<strong>an</strong> lords to induce Henry V1 to 4accept the terms agreed upon.Feb. 3. Battle of Mortimer's Cross.- 17. Second battle of St. Alb<strong>an</strong>'s.? Fortescue joins the L<strong>an</strong>castri<strong>an</strong> forces.March 4. Edward IV proclaimed.- 29. Fortescue present at the battle of Towton.<strong>The</strong> L<strong>an</strong>castri<strong>an</strong>s take refuge in Scotl<strong>an</strong>d.Apvii! 25. Agreement of the L<strong>an</strong>castri<strong>an</strong>s to surrender Berwickto the Scots.May. Berwick full of Scots. Carlisle besieged by the Scots.<strong>The</strong> siege raised by Montague.June 26. Fortescue <strong>an</strong>d others 'rear war' against Edward IVat Ryton <strong>an</strong>d Br<strong>an</strong>cepeth.- 28. Coronation of Edward IV.July 22. Death of Charles V11 of Fr<strong>an</strong>ce.1462. Feb. L<strong>an</strong>castri<strong>an</strong> plots for invading Engl<strong>an</strong>d.Feb. 20. Execution of the Earl of Oxford.June 1461-March 1462. Somerset <strong>an</strong>d Hungerford negotiateon the Continent in behalf of the L<strong>an</strong>castri<strong>an</strong> cause.1462. March. Somerset <strong>an</strong>d Hungerford return to Scotl<strong>an</strong>d. A fleetfor invading Engl<strong>an</strong>d assembles in the Seine.Apn'Z. Margaret <strong>an</strong>d Prince Edward go to the Continent.June 28. Treaty signed <strong>between</strong> Margaret <strong>an</strong>d Louis XI.Summer. Negotiations of the Scots with Edward IV.- <strong>The</strong> Northern castles lost by the L<strong>an</strong>castri<strong>an</strong>s.Sept. Warwick defeats the invading fleet.Oct. Margaret returns from Fr<strong>an</strong>ce <strong>an</strong>d recovers the Northerncastles ; is joined by Henry V1 in Northumberl<strong>an</strong>d.Nov. Henry V1 <strong>an</strong>d Margaret retire to Scotl<strong>an</strong>d.Dec. 24. Bamburgh <strong>an</strong>d Dunst<strong>an</strong>burgh surrender, <strong>an</strong>d Somersetsubmits to Edward IV.1463. j<strong>an</strong>. 6. Alnwick falls.Before A@. 29. Bamburgh <strong>an</strong>d two other castles recovered bythe L<strong>an</strong>castri<strong>an</strong>s.May. Alnwick goes over to the L<strong>an</strong>castri<strong>an</strong> side.Jwe. Henry V1 <strong>an</strong>d Margaret at Bamburgh.<strong>The</strong> L<strong>an</strong>castri<strong>an</strong>s dispersed by Warwick.Henry <strong>an</strong>d Margaret retire to Scotl<strong>an</strong>d.]g&. Margaret, Prince Edward, <strong>an</strong>d Fortescue go to the Continent.Sejt. 1-2. Interview of Margaret with Philip the Good atSt. Pol.<strong>The</strong> L<strong>an</strong>castri<strong>an</strong> exiles retire to St. Mighel in Barrois. Negotlationswith foreign courts.Dec. Somerset returns to the L<strong>an</strong>castri<strong>an</strong> allegi<strong>an</strong>ce.1461-1463. Fortescue writes the 'De Naturii Legis Naturte,'<strong>an</strong>d various tracts on the succession question.1464. ]<strong>an</strong>. Henry V1 at Edinburgh.Spring. Norham <strong>an</strong>d Skipton in Craven captured by theL<strong>an</strong>castri<strong>an</strong>s. L<strong>an</strong>castri<strong>an</strong> rising in L<strong>an</strong>cashire <strong>an</strong>dCheshire.March. Henry V1 at Bamburgh.April 25. Battle of Hedgeley Moor.May I. Edward IV privately married to Elizabeth Wydv~lle.- 8. Battle of Hexham.- I g. Execution of Somerset.- 27. Execution of Hungerford.Henry V1 retires to Scotl<strong>an</strong>d.June. Surrender of Alnwick <strong>an</strong>d Dunst<strong>an</strong>burgh. Capture ofBamburgh.Before Dec. Fortescue goes to Paris.Dec. Letter of Fortescue to Ormonde. Henry is safe <strong>an</strong>d outof the h<strong>an</strong>ds of his rebels.1465. March. ?Henry V1 at Edinburgh.July. Henry V1 captured in L<strong>an</strong>cashire <strong>an</strong>d sent to theTower.Summer. Fortescue goes to Paris.War of the Public Weal in Fr<strong>an</strong>ce.

INTRODUCTION.PART I.TIIE fifteenth century opens in two of the principal Contemcountriesof Europe with a revolution. On September 29, c:{,":i',:i1399, Richard 11 of Engl<strong>an</strong>d resigned the crown ; the next Engl<strong>an</strong>d<strong>an</strong>d theday he was deposed on charges, which were taken as Empire.proved by common notoriety, <strong>an</strong>d Henry IV was acceptedin his place. On August 20, I 400, a section of the electorsof the Holy Rom<strong>an</strong> Empire by <strong>an</strong> equally summary processdeposed their head, Wenzel king of Bohemia, <strong>an</strong>d on thefollowing day elected Rupert of the Palatinate in his stead.<strong>The</strong> fortunes of the two deposed monarchs had not beenunconnected. Richard's first wife, Anne of Bohemia, wasWenzel's half-sister: <strong>an</strong>d there is ext<strong>an</strong>t a letter fromWenzel to Richard, dated Sept. 24, 1397, in which heoffers Richard help against his rebellious nobles, in returnfor similar offers made by Richard to himself1. <strong>The</strong> comparisonis further worth making, because of the similarityof the charges which served to overthrow the two brothersin-law.Another comparison, which to students of English His- Comparisonof thetor^ is even better worth making, is the comparison <strong>between</strong> ~,,,1,,-the revolution of 1399 <strong>an</strong>d that of 1688. In both cases a 1399 <strong>an</strong>dgreat effort was made by the lawyers to preserve the for- ,688.malities of the constitution, <strong>an</strong>d to disguise by legal fictionsl Bekynton's Correspondence, I. hi. 287-9.B

?sal fic- what was in reality a breach of continuity: in both it wastlons.found necessary to pass over the immediate heir, so thatParliament had not merely, as in the case of Edward 11,to claim the right of setting aside <strong>an</strong> unworthy king, buthad implicitly to make the further claim to regulate thehfally were succession. So on both occasions probably m<strong>an</strong>y wereled furtherth<strong>an</strong> they carried by the course of events further along the path ofhad in- revolution th<strong>an</strong> they had intended. <strong>The</strong>re were m<strong>an</strong>y whotended.would gladly have seen Henry restored to his Duchy ofL<strong>an</strong>caster, <strong>an</strong>d who were prepared heartily to support himin insisting that Richard should ab<strong>an</strong>don his recent unconstitutionalproceedings <strong>an</strong>d return to his former mode ofgovernment, who yet felt themselves duped, when theyfound that he used the opportunity which they had givenhim to seat himself on the throne. So too there werem<strong>an</strong>y who were truly <strong>an</strong>xious that by me<strong>an</strong>s of the comingof the Prince of Or<strong>an</strong>ge the religion, laws, <strong>an</strong>d libertiesof Engl<strong>an</strong>d should be securely established in a free parliament,but who were disappointed when James 11'spusillallimity paved the way for the elevation of his sonixenry<strong>an</strong>din-law to the crown. Both Henry <strong>an</strong>d William came as\\ i111~1nc,,Ee the deliverers of a church which was threatened alike intleliverels doctrine <strong>an</strong>d in property by a hostile form of religion, <strong>an</strong>dof Chn~chI , of a nation perplexed <strong>an</strong>d unsettled by a feverish attempt"o".at arbitrary rule. In both cases questions of foreign policyForcignPO~,LY.had much to do with the result. But whereas at the closeof the seventeenth century it was absolutely necessary for thesalvation of Europe that Engl<strong>an</strong>d should be rescued fromher subservience to Fr<strong>an</strong>ce, at the close of the fourteenthcentury, on the other h<strong>an</strong>d, Fr<strong>an</strong>ce was by no me<strong>an</strong>s ad<strong>an</strong>gerous power. It was her very weakness which temptedthe unscrupulous <strong>an</strong>d hypocritical aggression of Henry V.<strong>The</strong>ory of In both cases one of the chief adv<strong>an</strong>tages secured by theroyalty.ch<strong>an</strong>ge of dynasty was that the royal authority was placedupon a proper footing, <strong>an</strong>d seen to rest upon the consent ofthe nation. Richard 11, like James 11, had imbibed <strong>an</strong>entirely baseless view of English monarchy. <strong>The</strong> assertionthat he had declared the laws to be in his own mouth <strong>an</strong>dbreast, is <strong>an</strong> exaggeration of his enemies: but iftrue, such l<strong>an</strong>guage is no worse th<strong>an</strong> James 11's prattleabout 'his sovereign authority, prerogative royal, <strong>an</strong>dabsolute power, which all his subjects were to obey withoutreserve'.' By the ch<strong>an</strong>ge of dynasty theories of thiskind were got rid of. Whether from choice or fromnecessity, the L<strong>an</strong>castri<strong>an</strong>s always professed to rule as constitutionalkings.<strong>The</strong> L<strong>an</strong>castri<strong>an</strong> period must always be of import<strong>an</strong>ce, Importasthe period in which political liberty, at <strong>an</strong>y rate in <strong>an</strong>ce of theL<strong>an</strong>castritheory,reached its highest point during the middle ages. <strong>an</strong> period.In fact the people acquired a larger measure of liberty th<strong>an</strong>they were able to use: <strong>an</strong>d the Commons, though boldin stating their griev<strong>an</strong>ces, were often helpless in devisingremedies. In the words of Dr. Stubbs, ' Constitutionalprogress had outrun administrative order2.'And this,combined with other causes which will be noticed later,made possible those disturb<strong>an</strong>ces which culminated in thecivil war, <strong>an</strong>d which wearied out the national patience,until even Tudor despotism seemed more tolerab!e th<strong>an</strong>confusion.<strong>The</strong> adv<strong>an</strong>tages of L<strong>an</strong>castri<strong>an</strong> rule were mainly prospec- Its adtive,<strong>an</strong>d its chief claim on our gratitude is the fact that it z:nysupplied the precedents on which the constitutional pnrty in prospectheseventeenth century based their resist<strong>an</strong>-tive.~e to that caricatureof Tudor despotism which the Stuarts attempted toperpetuate? Viewed in relation to contemporary history itwas prenlature ; <strong>an</strong>d it combines with the fruitless rising ofthe Hussites in Bohemia, with the abortive attempts of theChurch to reform itself in the Councils of Pisa, Const<strong>an</strong>ce,<strong>an</strong>d Basle, <strong>an</strong>d with the equally abortive attempts torestore administrative <strong>an</strong>d constitutional unity to the disintegratedGerm<strong>an</strong> Empire, to stamp upon the fifteenththat character of futility which has becn SO justlyascribed to it4.Hallam, Const. Hist. iii. 71. ' Weak as is the fourteenth' Stubh~, Const. Hist. iii. 269. century, the fifteenth is weakerS. C. H. iii. 2-5 ; cf. Rogers' still ; more firtde, more bloody,Gascoigne, pp. lviii; ff. more immoral.' S. C. H. ii. 624.B 2

Key-note ' <strong>The</strong> key-note of the L<strong>an</strong>castri<strong>an</strong> policy,' says Dr.of L<strong>an</strong>castri<strong>an</strong>Stubbs, 'was struck by Archbishop Arundel in Henry IV's~'olicy, its first Parliament, when he declared that Henry would beappeal tona~ional governed, not by his own "singular opinion, but by com-'Onsent. mon advice, counsel, <strong>an</strong>d consent l."' For the tendering ofthis 'common advice, counsel, <strong>an</strong>d consent,' there wereduring this period three org<strong>an</strong>s: 1. <strong>The</strong> Privy Council ;Privy 2. <strong>The</strong> Great Council ; 3. <strong>The</strong> Parliament. On theCouncil.character <strong>an</strong>d composition of the Privy Council duringthe L<strong>an</strong>castri<strong>an</strong> period, <strong>an</strong>d the schemes of Fortescue forGreat reorg<strong>an</strong>izing it, I have spoken at length elsewhere2. OnCouncil.the Great Council also something will be found in thesame place. Fortescue says nothing about it; perhaps, asI have there suggested, he disliked the institution as givingtoo much influence to the aristocracy. It forms howevera characteristic feature of L<strong>an</strong>castri<strong>an</strong> rule : for whereasin former reigns it appears as a mere survival of the oldbaronial parliaments, it now assumes special functions <strong>an</strong>da special position of its own, st<strong>an</strong>ding midway <strong>between</strong> thePrivy Council <strong>an</strong>d the Parliament, advising on matterswhich the former did not feel itself competent to settle, <strong>an</strong>dpreparing business for the meeting of the latter.ParIia- On the composition <strong>an</strong>d powers of Parliament Fortescuement.is also silent. Probably he considered them to be toofirmly settled <strong>an</strong>d too well known to require <strong>an</strong>y commentary.<strong>The</strong> increase of the power of parliament underthe L<strong>an</strong>castri<strong>an</strong>s is indeed too obvious to escape notice.' Never before,' says Dr. Stubbs, ' <strong>an</strong>d never again for moreth<strong>an</strong> two hundred years, were the Commons so strong asthey were under Henry IV"'Henry IV Henry IV came to the throne as the representative ofa Saviourof society. the ' possessioned ' classes--to use a contemporary expression4.<strong>The</strong> crude socialism of the Lollards, as the baronssaw, <strong>an</strong>d as the Churchmen were careful to point out,threatened the foundations not merely of the Church, butof all property. It was the mission of Henry IV to putS. C. H: iii. 14 S. C. H. iii. 72.Wotes to Chap. xv. below. ' Sharon Turner, iii. 105.down these <strong>an</strong>archical tendencies, to maintain vested interests<strong>an</strong>d the existing state of things. He came, in modernphrase, as a saviour of society. Richard 11, even in hisbest days, had not been very favourable to the interests ofthe propertied classes. He had not been forward in persecutingthe Lollard, <strong>an</strong>d he had wished to give freedom tothe serf. <strong>The</strong>se errors Henry was expected to correct.<strong>The</strong> second great object of Henry's reign was the main- Histen<strong>an</strong>ce of himself on the throne <strong>an</strong>d the continu<strong>an</strong>ce ofhis dynasty. From this point of view his reign was one himself.long struggle against foreign <strong>an</strong>d domestic enemies. Hisultimate success is a proof of his great ability, but he wasat no time free from <strong>an</strong>xiety. Hallaml sgeaks as ifHenry IV's submission to the dem<strong>an</strong>ds of the Commonswas unaccountable. But the causes of his weakness areplain enough. He was weak through his w<strong>an</strong>t of title,weak through the promises by which he had bound himselfto those whose aid had enabled hinl to win the crown,weak most of all through his w<strong>an</strong>t of money. It was this Hiswhich gave the Comnlons their opportunity, it was this pOve*y.which caused all the disasters of the reign, the rebellion ofthe Percies, the ill-success of the Welsh campaigns, thewretched state of Irel<strong>an</strong>d, the d<strong>an</strong>ger of Calais. <strong>The</strong> most' exquisite me<strong>an</strong>s '-to use Fortescue's phrase-of raisingmoney were resorted to; the constitutional character ofsome of them being, to say the least, questionable. Thisscarcity of money was due partly to the general w<strong>an</strong>t of Reqctionagalnstconfidence in the stability of the government which suc- him.ceded the brief enthusiasm in Henry's favour2, <strong>an</strong>d whichl Middle Ages, iii. 95.<strong>The</strong> letter of Philip Repingdon,the King's confessor, afterurdsBishop of Lincoln, datedMay 4, 1401, is worthy of careful~tudy In regard to this point. ItIS no mere rhetorical cornpositionmade up of phrases al\\ays kept1" stock <strong>an</strong>d not intended to fit"?Y thought in particular ; but itgibes a genuine picture of the un-Satisfactory state of the country,<strong>an</strong>d of the deep disappointmentfelt at the way in \vhich Henryhad belied the (perhaps unreasonablyhigh) expectations that hadbeen formed of him. <strong>The</strong> authoralludes in reference to Henry toLuke xuiv. 2 I, ' Nos autein sperabamusquia ipse esset redernpturusIsrael.' Bekynton's Correspondence,i. I 51-4 ; cf. also Engl.Chron., ed. Davies, pp. 23,28, 31 ;Hardyng, p. 371.

led people to hoard their gold <strong>an</strong>d silver, so that not onlywas none forthcoming to meet the dem<strong>an</strong>ds of the government,but- capital, which ought to have been employedproductively, was withdrawn from circulation, thus causingfor the time a general diminution of the resources of thecountry. As soon as the accession of Henry V had show11that the dyilasty was firmly established, abund<strong>an</strong>t suppliesDisturb- were at once at his comnl<strong>an</strong>dl. Another cause was the<strong>an</strong>ce ofcommerce. disturb<strong>an</strong>ce of commerce, <strong>an</strong>d consequent decline of thecustonls which followed the accession of Henry IV, owingpartly to the unsettled state of the relations <strong>between</strong>Engl<strong>an</strong>d <strong>an</strong>d Fr<strong>an</strong>ce" But the comn~ons could not be gotto believe in the poverty of the Government, <strong>an</strong>d Henrydid not dare to press for heavier taxation, for fear ofincreasing the already d<strong>an</strong>gerous amount of discontent.<strong>The</strong>un- In this way passed what the chronicler Hall has justlyquiet t~nleof~enry called ' the unquiet time of King Henry the Fourth.'1 ~ . Harassed as he was by enemies foreign <strong>an</strong>d domestic,deserted by m<strong>an</strong>y of the Lords, worried by the Commons,con~cious that he had lost the love of his people, jealous<strong>an</strong>d doubtful of his heir ; with a divided court <strong>an</strong>d brokenhealth, which his enemies regarded as a judgement uponhim, we c<strong>an</strong> hardly refuse him our sympathy, althoughwre may be of opinion that m<strong>an</strong>y of his troubles were selfcaused.<strong>The</strong> interest which he is said to have taken inthe solving of casuistical questions3, shows the morbidlines on which his burdened conscience was wearily working.<strong>The</strong>re is psychological if not historical truth in thestory that he expired with the sigh that God alone knewby what right he had obtained the crown4. It was ahrious choice that he should wish to be buried so nearthe m<strong>an</strong> whose son he had discrowned, if not done todeath.' S. C. H. iii. 87. S. C. H. iii. 65, note I.On this, <strong>an</strong>d on the general S Capgrave, Ill. Henr. pp. xxxiii,decline of Engl<strong>an</strong>d's maritime 109.power during the reigns of Henry * Monstrelet, ii. f. 164a, citedIV <strong>an</strong>d Henry VI, see notes to by Sharon Turner.chaps. \i. xrii. below, <strong>an</strong>d cf.<strong>The</strong> accession of Henry V was by no me<strong>an</strong>s his first .\ccessionappear<strong>an</strong>ce either as a statesm<strong>an</strong> or a warrior.He OfHenr~v.His previhadserved with distinction both in council <strong>an</strong>d in the oushistory.field, <strong>an</strong>d had received in both capacitics the th<strong>an</strong>ks ofparliament. He had had his own policy, <strong>an</strong>d his ownparty, who had urged him to claim the regency on theground that his father was incapacitated by the diseasefrom which he was suffering, which was said to be leprosy1.<strong>The</strong> words which Shakespeare puts into the mouth of Hisadv<strong>an</strong>tages.the dying Henry IV represent no more th<strong>an</strong> the literaltruth as to the adv<strong>an</strong>tages with which Henry V came tothe crown :'To thee it shall descend with better quiet,Better opinion, better confirmation;For all the soil of the achievement goesWith me into the earth2.'He reaped the benefit of <strong>an</strong> usurpation of which he hadnot shared the guilt. In accord<strong>an</strong>ce with these adv<strong>an</strong>tageshe adopted a policy almost ostentatiously conciliatory.Even the unjustifiable attack on Fr<strong>an</strong>ce may havebeen in part due to the same motive3. Only, if this washis idea, it was singularly falsified by the result. <strong>The</strong>causes which suspended for a time the outbreak of discord,did but make it the more intense when it came. And it is' I am inclined to think that Regiinine Principum, 111. ii. 15 :the above is the true account of a ' Guerra enim exterior tollit sediveryobscure tr<strong>an</strong>saction. Henry tiones et reddit cires magis un<strong>an</strong>i-Beaufort was said to have ' stired ' riles et concordes. Exemplumthe prince ' to have take ye gouver- enim hujus habemus in Rom<strong>an</strong>is,n<strong>an</strong>ce of yis Reume <strong>an</strong>d (of) ye quibus postquain defecerunt excrouneuppon hym ;' (so I would teriora bella intra se ipsos bellareconstrue the passage,) Rot. Parl. coeperunt.' 'For outward werreIv. 298 h ; cf. Sharon Turner, ii. aley)P inward strif, <strong>an</strong>d makeP362. Leprosy was a bar to the citeseyns be more acorded. Herdescentof real property ; Hardy, of we hauen ensample of theClose Rolls, I. xxxi. In Rymer, Romayns, for wh<strong>an</strong>ne hem failedexi. 635, is a certificate of the king's outward werre, thei by gunne tophysici<strong>an</strong>s that a certain person 1s haue werre among hemself.' MS.a leper, which is very interest- Digby, 233, fo. 142 c. To this'W yith reference to the nature of moti\e also Basin ascribes themedloval leprosy.warlike policy of Humphrey ofSecond Part of King Henry Gloucester. He too cites the15 Act iv. sc. 4. example of the Rom<strong>an</strong>s ; i. 189.Cf. Egidius Rom<strong>an</strong>us, De

3(n troduction,His reign only as developing causes, <strong>an</strong>d those evil causes, whichconst~tu-,ionallyun- hardly beg<strong>an</strong> to act until he had passed away, that theiml)oltalit. reign of Henry V has <strong>an</strong>y place in constitutional history.He did nothing perm<strong>an</strong>ent for the good of Engl<strong>an</strong>d, <strong>an</strong>dthe legacy which he left her was almost wholly evil : afalse ideal of foreign conquest <strong>an</strong>d aggression, a recklesscontempt for the rights <strong>an</strong>d feelings of other nations, <strong>an</strong>da restless incapacity for peace, in spite of exhaustion which<strong>The</strong>Sonth- had begun to show itself even in his own lifetime1. <strong>The</strong>amptonplot. llistory of the Southampton plot is characteristic of thehaste with which the L<strong>an</strong>castri<strong>an</strong>s sought to stifle <strong>an</strong>ythingwhich raised the d<strong>an</strong>gerous question of their title. <strong>The</strong>whole proceedings were so unconstitutional <strong>an</strong>d irregularthat they had to be specially legalized in the next Parlia-Beginning ment2. Even more noteworthy is the fact that 'this conortheWarsof spiracy was the first spark of the flame which in the courseIhrKores. of time consumed the two houses of L<strong>an</strong>caster <strong>an</strong>d York.Richard Earl of Cambridge was the father of KichardDuke of York, <strong>an</strong>d gr<strong>an</strong>dfather of Edward IV 3.'IICIIIYVI. But it was not till the house of L<strong>an</strong>caster had provedin the person of Henry V1 its entire incapacity to rule thekingdom, that the claims of the house of York were to beIIivisions put forward openly. '<strong>The</strong> troublous season of King Henry. the Sixth,' to use once more the words of Hall, may bedivided into three main periods: (I) from 1422 to 1437,the time of the minority proper 4 ; (2) from 1437 to 1450,the time of Henry's own attempt at governing with theaid of those who may from time to time have had theascend<strong>an</strong>cy with him; (3) from Cade's rising in 1450 to1461, the time of civil war. During the first of theseperiods the struggle is directly for preponder<strong>an</strong>ce in thecouncil, mainly <strong>between</strong> the adherents of Glouccster <strong>an</strong>d' That Henry's aggression \\,asdisapproved by some even of hisown subjects, see Gesta HenriciQuinti, p. xxxi ; cf. Pecock, liepressor,p. 516.Rot. Parl. iv. 64 ff. : ' utjudicia . . . pro bonis et legalibusjudiciis Itabere?ztur.'S Ellis,Historical Letters,lI.i.44.Henry did not legally come ofage till 1442, but from 1437 hebeg<strong>an</strong> to influence the course ofgovernment. See Rot. I'arl. v.438-9, which docu~nent may beregarded as marking the tr<strong>an</strong>sitionfrom the first to the second period.'Beaufort. During the second period the strugae is ratherfor influence with the king, for possession of the royal ear.~t first the contest as before is <strong>between</strong> Gloucester <strong>an</strong>dBeaufort. <strong>The</strong>n, when they disappear, it is <strong>between</strong> Suffolk,Somerset, <strong>an</strong>d Margaret on the one side, <strong>an</strong>d York <strong>an</strong>d hisadherents on the other. Owing to the unhappy weaknessof Henry both in will <strong>an</strong>d intellect, no party could feelsure of maintaining their ascend<strong>an</strong>cy with him, <strong>an</strong>d ofenjoying his support, unless they wholly monopolized hisear, <strong>an</strong>d excluded all other influences1. . Hence all theunconstitutional attempts of Margaret <strong>an</strong>d her partiz<strong>an</strong>sto keep first Gloucester <strong>an</strong>d then York from the royalpresence, which contributed largely to make the civil warinevitable. When that war broke out, the struggle forcomm<strong>an</strong>d of the king's person still continued; only it wasno longer carried on merely by intrigue <strong>an</strong>d party tactics,but depended for its issue upon the fate of battles.<strong>The</strong> marriage of Henry to Margaret of Anjou in 144.5 Henly'smar] iagewas a great misfortune not only to Engl<strong>an</strong>d 2, but also to disastlocs.the house of L<strong>an</strong>caster. By degrading the crown into <strong>an</strong>instrument of party warfare, she involved it in the ruin ofthe party of her choice 3. <strong>The</strong> death of Gloucester in 1447 Death ofGloucesterwas <strong>an</strong>other event which helped to bring matters to a <strong>an</strong>d I:enucrisis.Little good as he had done the house of L<strong>an</strong>caster fort.during his life, his death ~vas a very severe blow to it. Itcast <strong>an</strong> indelible suspicion on the existing government, <strong>an</strong>d1 'Pour ce que le roy Henry . . .?'a pas este . . . hommne tel que11 convenoit pour gouverner ungtel royaulme, chascun quy en aeu povoir s'est voullu enforchierd'en avoir le gouvernement,' &C.Waurin, ed. Uupont, ii. 282.a Gascoigne is especially strongon this point; e.g. pp. 203 ff.,219 ff.t Coliimynes remarksvery justlyOn the disastrous effect of this par-tiz<strong>an</strong> attitude of Margaret. SheOught, he says, to have acted asmediator bet~een the two parties,alld not to have identified herselfwith either ; Liv. vi. c. 12. Chastellainsays of her : '?'U as estCennemye trop tost et trop alnye hpeu y penser ; et sy te a port6gr<strong>an</strong>t gr~ef ton hayr, et ton aimerpeu de profit ;' vii. 129 f. Hemakes her confess that she hasbeen the ruin of Engl<strong>an</strong>d ; ib. 102.Cf. Bacon, Of Sectitions a dTroz~bles : ' When the Authorityof Princes is made but <strong>an</strong> Accessaryto a Cause, <strong>an</strong>d that there beother B<strong>an</strong>ds that tie faster th<strong>an</strong>the B<strong>an</strong>d of Sovereignty, Kingsbegin to be put almost out ofpossession.' Cf. id. Of Faction.

it tr<strong>an</strong>sferred the position of heir-presumptive <strong>an</strong>d leader ofthe opposition to a m<strong>an</strong> whose abilities were far greaterth<strong>an</strong> those of Gloucester, while his interests were diametricallyopposed to those of the house of L<strong>an</strong>caster, instead ofbeing identical with them. A few weeks later died CardinalBeaufort, <strong>an</strong>d the stage was thus cleared for younger actors.Somerset <strong>an</strong>d York were both absent from Engl<strong>an</strong>d, <strong>an</strong>dMinistry of Suffolk was omnipotent at court. He showed a rigorousdetermination to exclude not merely from power, but evenfrom the king's presence, all but those who were prepared tobe the subservient ministers of his will l. <strong>The</strong> same policywas pursued with reference to the local administrationz.<strong>The</strong> reaction caused by this arrog<strong>an</strong>ce <strong>an</strong>d partiality, <strong>an</strong>dHis im- the ill-success of his foreign policy 3, proved his ruin. Bypeachment.1450 the popular. indignation could no longer be restrained,<strong>an</strong>d his impeachment was resolved on by the Commons.<strong>The</strong> ultimate decision of the question is <strong>an</strong> inst<strong>an</strong>ce of atendency, which appears more th<strong>an</strong> once in this time ofTendency weakness <strong>an</strong>d decline of true political life; the tendency,to shi~kconstito- namely, to throw the responsibility for questionable actionstional re- upon the crown, <strong>an</strong>d so to shift it from the shoulders of thosesponsibi-Iity. who constitutionally ought to bear it. At the time ofHenry's marriage the Lords protested that the king hadbeen moved to the thought of peace ' onely by oure Lorde,'<strong>an</strong>d not by 'the Lordes, or other of your suggettes4.' Sonow the king, 'by his owue advis, <strong>an</strong>d not reportyng hymto thy advis of his Lordes, nor by wey of judgement,'' Even the sermons preachedbefore the king were subjected to arigorous censorship ; Gascoigne,p. 191 ; cf. Gregory, pp. xxiii, 203.Rot. Parl. v. 181 b, <strong>an</strong>d notesto Chap. xvii, below.SCf. Gascoigne, p. 219 : ' Et sicfacta est alienacio ... predictarumterrarum . . . sine aliqua pacefinali conclusa . .. inter illa duoregna.' Henry's subsequent protestthat the cession of Maine wasonly made in consideration of asecure peace (Rymer, xi. 204,March IS, 1448) was, in the faceof the actual facts, not worth theparchment it was written on. <strong>The</strong>same may be said of the declarationof Suffolk's loyalty ; Rot.Parl. v. 447 b.* Rot. Parl. v. 102 b. <strong>The</strong> sametendency appears in the PrivyCouncil. See the case of Somerset'sapplication for a gr<strong>an</strong>t, citedin the notes to Chap. xix. below.In the challenge which Henry Vsent to the Dauphin in 1415, it isstated that none of his counsellorshad dared to counsel him in sohigh a matter ; Rymer, ix. 313.b<strong>an</strong>ished Suffolk for five years, the Lords protesting thatthis ' proceded not by their advis <strong>an</strong>d counsell, but wasdoon by the kynges. - owne deme<strong>an</strong>aunce <strong>an</strong>d rule l.' In allthese cases the Lords ought, if they approved of what wasdone, to have accepted their share of the responsibility, or,if they disapproved, they should have fr<strong>an</strong>kly opposed it.<strong>The</strong>ir actual course was a piece of political cowardice. <strong>The</strong>whole proceedings in the case of Suffolk were most uncon-&utional, a flagr<strong>an</strong>t evasion of the right of the Commonsto bring <strong>an</strong> accused minister to trial before the House ofLords" <strong>The</strong> idea of Henry was no doubt to find a compromisewhereby the Commons might be satisfied, <strong>an</strong>d yetSuffolk might be saved. He failed egregiously in both.Suffolk was murdered at sea, <strong>an</strong>d this gave the signal forall the mischief that followed. <strong>The</strong> Commons of Kent rose Rising orunder Cade, complaining, among other things, that ' the Cade.fals traytur Pole that was as fals as Fortager (Vortigern). . . apechyd by all the h011 comyns of Ingelond, . . .myght not be suffryd to dye as ye law wolde3.'<strong>The</strong> rising of Cade was but the climax of a processwhich had long been going on. <strong>The</strong> government hadgradually been losing all hold upon the country, <strong>an</strong>d inthe general paralysis of the central administration localdisorder had increased to a frightful extent4. <strong>The</strong> causes Causes otgovel n-of these 'troubles <strong>an</strong>d debates5' are precisely those evilsagainst which Fortescue's proposed reforms are mainly weakness.Rot. Parl. v. 183.This right was not in theslightest degree affected by Suffolk'sresignation of his privilegesas a peer.S Three Fifteenth Century Chronicles,p. 95. According to Basin,i. 25 I - 2, Somerset f<strong>an</strong>ned thePopular indignation against Suffolk,in order to divert attentionfroin his own military failures.<strong>The</strong> year 1443 e.g. seems tohave been specially troublous.rhere were disputes <strong>between</strong> theEarl of Northumberl<strong>an</strong>d <strong>an</strong>dKemp the Archbishop of York,P. P. C. v. 309, cf. ib. 268-9, 273 ;<strong>between</strong> Lord Grey of Ruthin <strong>an</strong>dthe town of Northampton, ib. 305 ;<strong>between</strong> S. Mary's Abbey, York,<strong>an</strong>d the Corporation of that city,ib. 225, 232 ; <strong>between</strong> FountainsAbbey <strong>an</strong>d Sir John Neville, ib.241 : there were rists at Salisbury,ib. 247-8 ; <strong>an</strong>d in London, ib.277-8. In 1437 the whole countrywas so disturbed that copies of theStatute of Winchester were sent toall the sheriffs, with orders for itsenforcement ; ib. 83.See below, Chap. xvii.

directed, <strong>an</strong>d they must therefore be investigated somewhatin detail.Poveit~. One great cause of the weakness of the government wasno doubt its poverty. <strong>The</strong> revenue both central <strong>an</strong>d local1was hopelessly encumbered, largely by gr<strong>an</strong>ts of <strong>an</strong>nuities<strong>an</strong>d pensions to persons who were in reality much richerth<strong>an</strong> the crown2. <strong>The</strong> notes to this work will show indetail how every br<strong>an</strong>ch of the public service was const<strong>an</strong>tlyin arrear3. It was seldom if ever possible to waituntil the supplies gr<strong>an</strong>ted by Parliament were actuallyI,o<strong>an</strong>s. collected. Parliament itself generally gave authority tothe Council to raise lo<strong>an</strong>s on the security of the taxes.Where this parliamentary s<strong>an</strong>ction was given, <strong>an</strong>d thelo<strong>an</strong>s were punctually repaid, this system was perhapsconstitutionally unobjectionable 4. But the fin<strong>an</strong>cial resultwas disastrous. Fortescue estimates the loss to the kingat ' the fourth or fifth penny of his revenues ".' Lo<strong>an</strong>s wereconst<strong>an</strong>tly asked for from individuals, corporations, <strong>an</strong>dtowns, <strong>an</strong>d sometimes in a way which seems distinctlyunconstitutional^ Beaufort was the chief lender <strong>an</strong>d lo<strong>an</strong>On the state of the local revenue,see notes to Chap. xv.below.See notes to Chap. vi. below,<strong>an</strong>d cf. Gascoigne, p. 158.S See especially notes to Chaps.vi, <strong>an</strong>d vii.A list of towns <strong>an</strong>d persons,with the sums which they wereexpected to lend under Parliamentaryauthority,is in P.P. C. iv. 316K(1436). <strong>The</strong>re are innumerableentries in the Cal. Rot. Pat. 'delnutuo faciendo per totum regnum;' 273 a, 274 b, 275 b, 276 b,280 b, 284 b, 289 b, 293 b, 295 a,296 a. U7hether all these had parliamentaryauthority I c<strong>an</strong>not say.<strong>The</strong> Lords of the Council <strong>an</strong>dothers had frequently to bindthemselves not to allow the assignmentsmade for repayment oflo<strong>an</strong>s to be tampered whh ; P.P. C.iv. 145 ; Rot. Parl. iv. 275 b. Thisprecaution had been taken underHenry V ; ib. 117.That itwas not unnecessary is shown bythe fact that in 1442 Beaufortalone supported the Treasurer inresisting <strong>an</strong> attempt to assign revenuethat had been already appropriated; P. P. C.V. 216, cf. 220.But in 1443 he agreed to a gr<strong>an</strong>tout of the customs of London,' notwithst<strong>an</strong>dyng <strong>an</strong>y assignementmaade before, <strong>an</strong>d notwithst<strong>an</strong>dyng<strong>an</strong>y estatut act or orden<strong>an</strong>ce; ' ib. 227.Chap. v. below.In 1430 the Pope lent Henrymoney ; 1'. P. C. iv. 343. In 1437a special appeal was made to theclergy; ib. v. 42. Dr. Stubbs(C. H. iii. 276 note) has tried tom~n~rni~e the charge of unconstitutionaltaxation brought againstthe L<strong>an</strong>castri<strong>an</strong> kings. One document,he thinks, is wrongly assignedto that period. Other cases' ~nvolke only the sort of lo<strong>an</strong>scol~tractor to the government '. <strong>The</strong> king's jewels werein pawn '. And the government seem not tohave been above such petty acts of tyr<strong>an</strong>ny as exactingthe fines for respite of knighthood twice over 3. Fortescue Exquisitellimself admits that the poverty of the king compels him me<strong>an</strong>s.g to fynde exquysite me<strong>an</strong>es of geyting of good 4.' It ishardly likely that in this he is thinking oidy of the reignof ~dward IV. It is obvious that <strong>an</strong> administration thusstarved could not be efficient. <strong>The</strong> remedies which Fortes~ue'bFortescue proposes for this state of things are a largereme'"e"increase in the perm<strong>an</strong>ent endowment of the crown, <strong>an</strong>dthe making of that 'livelod ' inalienable, a resumption ofgr<strong>an</strong>ts, the limitation of the king's power of giving bymaking the consent of the council necessary, <strong>an</strong>d a systemwhich were s<strong>an</strong>ctioned by Parliament,'though, if they were notactually s<strong>an</strong>ctioned by Parliament,their constitutional characterwould still be doubtful. But thefollowing inst<strong>an</strong>ce (which Dr.Stubbs does not cite) seems tooclear to be explained away.RIGHT trusty, &c.Howe it bethat . . . . we . . . . charged youeither to have sende . . . . the cc.marE, like as ye aggreed . . . . tolenne us, . . . .or elles to have apperedpersonally before us <strong>an</strong>doure Counsaille ; . . . . Neverthelesse. . . . ye neyther have sendethe saide money, nor appered . . . .For so moche we write.. . . straitelycharging you, that as ye woleschewe to be noted <strong>an</strong>d taken fora letter <strong>an</strong>d breker of tharmee,whiche is appointed to be sendeunto our saide duchie (of Guye?ne),. . . . ye withoute delay. . . .either sende by the berer heroffhe saide cc. mar?, . . . .or commeIn alle possible haste personellyoure saide Counsaille, . . . .uPoii the paine abovesaide.' (July,'453,) P. P. C. vi. 143, cf. ib. 330.To require a person to sendmoney by the bearer, or to appearbefore the Council under pain ofbeing 'noted' as a disloyal sub-ject, is surely as arbitrary a proceedingas c<strong>an</strong> well be imagined.That the m<strong>an</strong> had promised tolend the money does not affect theconstitutional question, if the promisewas one which the govern-ment had no right to exact. EdwardIV's fin<strong>an</strong>cial measures wereperhaps only a reduction to systemof the hints furnished by his predecessors.' For Beaufort's lo<strong>an</strong>s, seeP. P. C. iv. <strong>an</strong>d v. passim.'e.g. P. P. C.iv.214, vi.106,&c. Cf. notes to Chap. vii.At least a petition of the Commonsthat this might not be donewas refused in 1439 ; Rot. Parl. v.26 b.Chap. v. below. Accordingto De Coussy, c. 42, ed. Buchon,p. 83 b, the poverty of theroyal household was sometimes soextreme, that the king <strong>an</strong>d queenwere in positive w<strong>an</strong>t of a dinner.On one occasion the Treasurerhad to redeem a robe which theking had given to St. Alb<strong>an</strong>'s,because it was the only decent onewhich he possessed ; Whetham-stede, i. 323. That this povertywas one great cause of the unpopularityof the government ofHenry VI, see Eng. Chron., p. 79.

Powe~ 2ndinsobordiofof ready money payments, whereby a saving of twenty ortwenty-five per cent. on the ordinary expenditure may beeffected '.Another main cause of the paralysis of the governmentwas the overgrown power <strong>an</strong>d insubordination of the nobles.thenobles. ' <strong>The</strong> two c<strong>an</strong>kers of the time were the total corruption ofthe Church, <strong>an</strong>d the utter lawlessness of the aristocracy 2.'<strong>The</strong> condition of the English Church <strong>an</strong>d the policy <strong>an</strong>drelations of the L<strong>an</strong>castri<strong>an</strong> kings towards it are subjcctswhich, however interesting, c<strong>an</strong>not be discussed here. <strong>The</strong>ydid not come within the scope of Fortescue's writings, <strong>an</strong>dif they had, his orthodoxy <strong>an</strong>d optimism would probablyhave made him averse to discussing them. But the reductionof the power <strong>an</strong>d influence of the nobles is one ofthe chief objects which he has in view, arid is the end towhich most of his reforms are directed. <strong>The</strong> d<strong>an</strong>ger tothe crown from 'over-mighty subjects' is one that is neverabsent from his mind. This therefore is a question whichmust be carefully discussed.Or~gil~ of For the origin of the evil, in the form in which ittlie e\ilEd- appears during our period, we must go back to the timeward 111. of Edward 111. <strong>The</strong> evils of the older feudalism had beensternly repressed by William I <strong>an</strong>d Henry I. Henry I1had excluded feudal principles from the framework of thegovernment. Edward I had eliminated them from theworking of the constitution. <strong>The</strong> reign of Edward I1 isa period of tr<strong>an</strong>sition during which the lords tried for amoment to recover the ground which they had lost; butthe Despencers met then1 by a combination of the Crown<strong>an</strong>d Commons, <strong>an</strong>d for the first time placed upon theStatute Book a declaration of the principles of parlia-mentary government. <strong>The</strong> long reign of Edward I11completed the work which the Despencers, from whatevermotives, had begun ; <strong>an</strong>d the Commons steadily won theirway to a legal equality with the elder estate of the' See Chaps. vi-xi, xiv, xix, xx, tion, p. lviii.below, <strong>an</strong>d the notes thereto . See below, Introduction, PartRogers' Gascoigne, Introduc- I I I.baronagc <strong>The</strong> latter could no longer dream of monopolizingthe government as they had attempted to do under Henry111.<strong>The</strong> Commons might be led, might be influenced,they could not be ignored. But though the great lordscould not hope for a de jzr!~e monopoly of power, theirinfluence de fact0 was still enormous. And it increasedullder Edward 111, largely owing to the effects of theFrench wars. <strong>The</strong> old feudal system of military service Ch<strong>an</strong>ge inbeing to a'great extent obsolete, <strong>an</strong>d being besides wholly the of mil~tnry sqsteluunsuited to the carrying on of a prolonged foreign war, service.Edward I11 introduced a new method of raising forces,whereby the Crown contracted, or, as it was called, indentedwith lords <strong>an</strong>d others for the supply of a certainnumber of men at a fixed rate of pay. Thus not only did Itsresults.the lords make profits, often very large, out of theircontracts with the government, <strong>an</strong>d enrich themselveswith prisoners <strong>an</strong>d plunder while the war lasted ; but whenthe war was over, they returned to Eng!<strong>an</strong>d at the headof b<strong>an</strong>ds of men accustomed to obey their orders, incapacitatedby long warfare for the pursuits of settled <strong>an</strong>dpeaceful life, <strong>an</strong>d ready to follow their late masters on <strong>an</strong>yturbulent enterprise. <strong>The</strong>se considerations will largelyaccount for the ease with which under Richard 11 a combinationof a few powerful nobles was able to overbear the -might of the Crown. <strong>The</strong> reign of Edward 111 was more- Pseudooverthe period of that pseudo-chivalry, which, under agarb of external splendour <strong>an</strong>d a factitious code of honour, feudal~sm.failed to conceal its ingrained lust <strong>an</strong>d cruelty, <strong>an</strong>d itsreckless contempt for the rights <strong>an</strong>d feelings of all whowere not admitted within the charmed circle; <strong>an</strong>d it sawthe beginning of that bastard feudalism, which, in place ofthe primitive relation of a lord to his ten<strong>an</strong>ts, surroundedthe great m<strong>an</strong> with a horde of retainers, who wore hislivery <strong>an</strong>d fought his battles, <strong>an</strong>d were, in the most literalSense of the words, in the law courts <strong>an</strong>d elsewhere,' Addicti jurare in verba magistri ; 'while he in turn maintained their quarrels <strong>an</strong>d shielded their

crimes from punishment'. This evil, as we shall see, rcachcdits greatest height during the L<strong>an</strong>castri<strong>an</strong> period.power <strong>The</strong> independence of the great lords thus fostered bythe tendencies of Edward 111's reign <strong>an</strong>d by the events~~''d~~n*-tcreased by which happened under Richard 11, was still further in-Henry 1V'screased by the accession of Henry 1V. To some of them,the Percies <strong>an</strong>d Arundels especially, Henry largely owedhis crown. It is true that having a great stake in themainten<strong>an</strong>ce of the government which they had set upthe lords contributed considerable sums to the support ofHenryz. But this very feeling that they were necessaryto him increased their sense of independence ; <strong>an</strong>d in 1404they showed how they construed their obligations tothe Crown, refusing to find Northumberl<strong>an</strong>d guilty oftreason for his share in the rebellion of the Percies in 1403,<strong>an</strong>d treating the matter as a mere case of private war<strong>between</strong> him <strong>an</strong>d the Earl of Westmorel<strong>an</strong>d. Even ifthis had been a colourable view to take of the affair, thissort of quasi-s<strong>an</strong>ction given to private war, a curse fromwhich Engl<strong>an</strong>d had been alrnost free from the days ofHenry 113, was of evil omen. To a private war <strong>between</strong>these very families of Percy <strong>an</strong>d Neville the <strong>an</strong>nalistWilliam Worcester traces the origin of the civil war4.Anyhow one cause of that war was this insubordinationof the aristocracy, of which private wars were but onesymptom among m<strong>an</strong>y. If, as Mr. Bright thinks 5, theCommons looked to Henry as their champion againstbaronial disorder, they must have been grievously disap-~ h ~ pointed. ~ ~ i l <strong>The</strong> evil was aggravated by the French wars ofaggravated Henry V. Causes came into operation similar to thoseg;,":h which we have traced under Edward 111 ; only here theyHenry V. acted with worse effect owing to the degeneration incharacter of the French wars themselves. <strong>The</strong> sternl ' <strong>The</strong> livery of a great lord was pp. 120 ff.as effective security to a male- ' English in Fr<strong>an</strong>ce, ii. [770]:factor as was the benefit of clergy ' Initium fuit maximorum dolorum)c the criminous clerk ; ' S. C. H. in Anglia.'111. 533. ' Bright, English History, i.P.P.C.,I.xxvii,xxxiii, 102ff. 277.8 See Allen on the Prerogative,of Henry V left no room for <strong>an</strong>y of thatgraceful chivalry which had thrown a glamour, howeversuperficial, over the warfare of Edward 111 <strong>an</strong>d his greaterson. And things became worse, when to other debasinginfluences was added the fury which is born of failure.<strong>The</strong> English lords ousted from Fr<strong>an</strong>ce returned to Engl<strong>an</strong>dat the head of b<strong>an</strong>ds of men brutalized by long warfare,demoralized by the life of camps <strong>an</strong>d garrisons, <strong>an</strong>d readyfor <strong>an</strong>y desperate adventure. Even during Henry V's lifetimethis evil had begun to show itself1, <strong>an</strong>d it did notdiminish under the weak rule of his successor2. Andthese were the men by whom the battles of the civil warswere fought.M<strong>an</strong>y of the lords were moreover enormously rich. Richesof<strong>The</strong>ir estates were concentrated in fewer h<strong>an</strong>ds, <strong>an</strong>d thel<strong>an</strong>ds of a m<strong>an</strong> like Warwick represented the accumulationsof two or three wealthy families 3. <strong>The</strong>y engrossedoffices as greedily as l<strong>an</strong>ds 4, their pensions <strong>an</strong>d<strong>an</strong>nuities exhausted the revenues of the crown6, theymade large fortunes out of the French wars which drainedthe royal exchequer6, <strong>an</strong>d they were among the chief woolgrowers<strong>an</strong>d sometimes wool-merch<strong>an</strong>ts in the kingdom7.And this wealth of the great lords appeared all the more contrastedwith thestriking when contrasted with the poverty of the crowns: povertyof<strong>an</strong>d the contrast comes out strongly in the dem<strong>an</strong>d made the C~OW~LbyFortescue, that the king shall have for his extraordinaryexpenditure more th<strong>an</strong> the revenues of <strong>an</strong>y lord", <strong>an</strong>d inthe exultation with which he declares, that if only theking's offices are really given by the king, 'the grettestlordes livelod in Engl<strong>an</strong>de mey not suffice to rewarde so' See Political Songs, -. 11. xxvii. for militarv service: Paston Let-112. ters, i. 3 jg ff.Cf. De Coussy, p. 183. Cf. Rot. Parl. iii. 497, v. 13 a,See notes to Chap. ix. below. 274 b ; English in Fr<strong>an</strong>ce, ii. 443.See notes to Chap. xvii. 'So pore a kyng was neverbe!ow.seene." See notes to Chap.vi. below. 'Nor richkre lordes all by-Cf; Gascoigne, p. I 58.dene.'Cf. Rogers' Gascoigne, Intro- -Political Songs, ii. 230 ; cf.ductlon, p. xxvi, <strong>an</strong>d the list of Rogers, Work <strong>an</strong>d Wages, p. 20.Fastolf~ claims against the crown Below, Chap. ix.C