How to Win Friends and Influence People - Mohit K. Arora

How to Win Friends and Influence People - Mohit K. Arora

How to Win Friends and Influence People - Mohit K. Arora

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

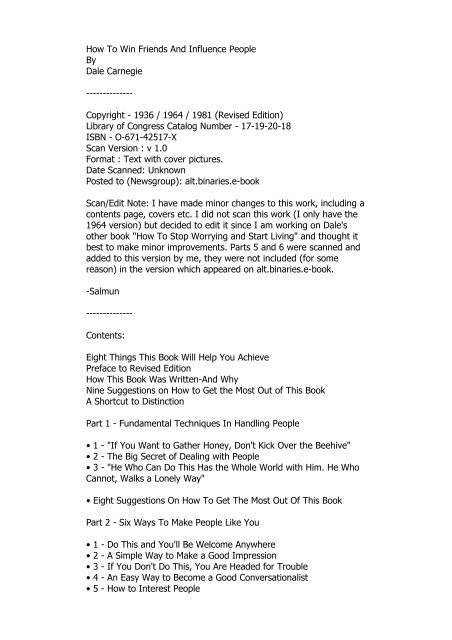

<strong>How</strong> To <strong>Win</strong> <strong>Friends</strong> And <strong>Influence</strong> <strong>People</strong><br />

By<br />

Dale Carnegie<br />

--------------<br />

Copyright - 1936 / 1964 / 1981 (Revised Edition)<br />

Library of Congress Catalog Number - 17-19-20-18<br />

ISBN - O-671-42517-X<br />

Scan Version : v 1.0<br />

Format : Text with cover pictures.<br />

Date Scanned: Unknown<br />

Posted <strong>to</strong> (Newsgroup): alt.binaries.e-book<br />

Scan/Edit Note: I have made minor changes <strong>to</strong> this work, including a<br />

contents page, covers etc. I did not scan this work (I only have the<br />

1964 version) but decided <strong>to</strong> edit it since I am working on Dale's<br />

other book "<strong>How</strong> To S<strong>to</strong>p Worrying <strong>and</strong> Start Living" <strong>and</strong> thought it<br />

best <strong>to</strong> make minor improvements. Parts 5 <strong>and</strong> 6 were scanned <strong>and</strong><br />

added <strong>to</strong> this version by me, they were not included (for some<br />

reason) in the version which appeared on alt.binaries.e-book.<br />

-Salmun<br />

--------------<br />

Contents:<br />

Eight Things This Book Will Help You Achieve<br />

Preface <strong>to</strong> Revised Edition<br />

<strong>How</strong> This Book Was Written-And Why<br />

Nine Suggestions on <strong>How</strong> <strong>to</strong> Get the Most Out of This Book<br />

A Shortcut <strong>to</strong> Distinction<br />

Part 1 - Fundamental Techniques In H<strong>and</strong>ling <strong>People</strong><br />

• 1 - "If You Want <strong>to</strong> Gather Honey, Don't Kick Over the Beehive"<br />

• 2 - The Big Secret of Dealing with <strong>People</strong><br />

• 3 - "He Who Can Do This Has the Whole World with Him. He Who<br />

Cannot, Walks a Lonely Way"<br />

• Eight Suggestions On <strong>How</strong> To Get The Most Out Of This Book<br />

Part 2 - Six Ways To Make <strong>People</strong> Like You<br />

• 1 - Do This <strong>and</strong> You'll Be Welcome Anywhere<br />

• 2 - A Simple Way <strong>to</strong> Make a Good Impression<br />

• 3 - If You Don't Do This, You Are Headed for Trouble<br />

• 4 - An Easy Way <strong>to</strong> Become a Good Conversationalist<br />

• 5 - <strong>How</strong> <strong>to</strong> Interest <strong>People</strong>

• 6 - <strong>How</strong> To Make <strong>People</strong> Like You Instantly<br />

• In A Nutshell<br />

Part 3 - Twelve Ways To <strong>Win</strong> <strong>People</strong> To Your Way Of Thinking<br />

• 1 - You Can't <strong>Win</strong> an Argument<br />

• 2 - A Sure Way of Making Enemies—<strong>and</strong> <strong>How</strong> <strong>to</strong> Avoid It<br />

• 3 - If You're Wrong, Admit It<br />

• 4 - The High Road <strong>to</strong> a Man's Reason<br />

• 5 - The Secret of Socrates<br />

• 6 - The Safety Valve in H<strong>and</strong>ling Complaints<br />

• 7 - <strong>How</strong> <strong>to</strong> Get Co-operation<br />

• 8 - A Formula That Will Work Wonders for You<br />

• 9 - What Everybody Wants<br />

• 10 - An Appeal That Everybody Likes<br />

• 11 - The Movies Do It. Radio Does It. Why Don't You Do It?<br />

• 12 - When Nothing Else Works, Try This<br />

• In A Nutshell<br />

Part 4 - Nine Ways To Change <strong>People</strong> Without Giving Offence Or<br />

Arousing Resentment<br />

• 1 - If You Must Find Fault, This Is the Way <strong>to</strong> Begin<br />

• 2 - <strong>How</strong> <strong>to</strong> Criticize—<strong>and</strong> Not Be Hated for It<br />

• 3 - Talk About Your Own Mistakes First<br />

• 4 - No One Likes <strong>to</strong> Take Orders<br />

• 5 - Let the Other Man Save His Face<br />

• 6 - <strong>How</strong> <strong>to</strong> Spur Men on <strong>to</strong> Success<br />

• 7 - Give the Dog a Good Name<br />

• 8 - Make the Fault Seem Easy <strong>to</strong> Correct<br />

• 9 - Making <strong>People</strong> Glad <strong>to</strong> Do What You Want<br />

• In A Nutshell<br />

Part 5 - Letters That Produced Miraculous Results<br />

Part 6 - Seven Rules For Making Your Home Life Happier<br />

• 1 - <strong>How</strong> <strong>to</strong> Dig Your Marital Grave in the Quickest Possible Way<br />

• 2 - Love <strong>and</strong> Let Live<br />

• 3 - Do This <strong>and</strong> You'll Be Looking Up the Time-Tables <strong>to</strong> Reno<br />

• 4 - A Quick Way <strong>to</strong> Make Everybody Happy<br />

• 5 - They Mean So Much <strong>to</strong> a Woman<br />

• 6 - If you Want <strong>to</strong> be Happy, Don't Neglect This One<br />

• 7 - Don't Be a "Marriage Illiterate"<br />

• In A Nutshell<br />

--------------<br />

Eight Things This Book Will Help You Achieve

• 1. Get out of a mental rut, think new thoughts, acquire new<br />

visions, discover new ambitions.<br />

• 2. Make friends quickly <strong>and</strong> easily.<br />

• 3. Increase your popularity.<br />

• 4. <strong>Win</strong> people <strong>to</strong> your way of thinking.<br />

• 5. Increase your influence, your prestige, your ability <strong>to</strong> get things<br />

done.<br />

• 6. H<strong>and</strong>le complaints, avoid arguments, keep your human contacts<br />

smooth <strong>and</strong> pleasant.<br />

• 7. Become a better speaker, a more entertaining conversationalist.<br />

• 8. Arouse enthusiasm among your associates.<br />

This book has done all these things for more than ten million readers<br />

in thirty-six languages.<br />

--------------<br />

Preface <strong>to</strong> Revised Edition<br />

<strong>How</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Win</strong> <strong>Friends</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Influence</strong> <strong>People</strong> was first published in 1937<br />

in an edition of only five thous<strong>and</strong> copies. Neither Dale Carnegie nor<br />

the publishers, Simon <strong>and</strong> Schuster, anticipated more than this<br />

modest sale. To their amazement, the book became an overnight<br />

sensation, <strong>and</strong> edition after edition rolled off the presses <strong>to</strong> keep up<br />

with the increasing public dem<strong>and</strong>. Now <strong>to</strong> <strong>Win</strong> <strong>Friends</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

InfEuence <strong>People</strong> <strong>to</strong>ok its place in publishing his<strong>to</strong>ry as one of the<br />

all-time international best-sellers. It <strong>to</strong>uched a nerve <strong>and</strong> filled a<br />

human need that was more than a faddish phenomenon of post-<br />

Depression days, as evidenced by its continued <strong>and</strong> uninterrupted<br />

sales in<strong>to</strong> the eighties, almost half a century later.<br />

Dale Carnegie used <strong>to</strong> say that it was easier <strong>to</strong> make a million dollars<br />

than <strong>to</strong> put a phrase in<strong>to</strong> the English language. <strong>How</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Win</strong> <strong>Friends</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>Influence</strong> <strong>People</strong> became such a phrase, quoted, paraphrased,<br />

parodied, used in innumerable contexts from political car<strong>to</strong>on <strong>to</strong><br />

novels. The book itself was translated in<strong>to</strong> almost every known<br />

written language. Each generation has discovered it anew <strong>and</strong> has<br />

found it relevant.<br />

Which brings us <strong>to</strong> the logical question: Why revise a book that has<br />

proven <strong>and</strong> continues <strong>to</strong> prove its vigorous <strong>and</strong> universal appeal?<br />

Why tamper with success?<br />

To answer that, we must realize that Dale Carnegie himself was a<br />

tireless reviser of his own work during his lifetime. <strong>How</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Win</strong><br />

<strong>Friends</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Influence</strong> <strong>People</strong> was written <strong>to</strong> be used as a textbook<br />

for his courses in Effective Speaking <strong>and</strong> Human Relations <strong>and</strong> is still<br />

used in those courses <strong>to</strong>day. Until his death in 1955 he constantly<br />

improved <strong>and</strong> revised the course itself <strong>to</strong> make it applicable <strong>to</strong> the<br />

evolving needs of an every-growing public. No one was more

sensitive <strong>to</strong> the changing currents of present-day life than Dale<br />

Carnegie. He constantly improved <strong>and</strong> refined his methods of<br />

teaching; he updated his book on Effective Speaking several times.<br />

Had he lived longer, he himself would have revised <strong>How</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Win</strong><br />

<strong>Friends</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Influence</strong> <strong>People</strong> <strong>to</strong> better reflect the changes that have<br />

taken place in the world since the thirties.<br />

Many of the names of prominent people in the book, well known at<br />

the time of first publication, are no longer recognized by many of<br />

<strong>to</strong>day's readers. Certain examples <strong>and</strong> phrases seem as quaint <strong>and</strong><br />

dated in our social climate as those in a Vic<strong>to</strong>rian novel. The<br />

important message <strong>and</strong> overall impact of the book is weakened <strong>to</strong><br />

that extent.<br />

Our purpose, therefore, in this revision is <strong>to</strong> clarify <strong>and</strong> strengthen<br />

the book for a modern reader without tampering with the content.<br />

We have not "changed" <strong>How</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Win</strong> <strong>Friends</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Influence</strong> <strong>People</strong><br />

except <strong>to</strong> make a few excisions <strong>and</strong> add a few more contemporary<br />

examples. The brash, breezy Carnegie style is intact-even the thirties<br />

slang is still there. Dale Carnegie wrote as he spoke, in an intensively<br />

exuberant, colloquial, conversational manner.<br />

So his voice still speaks as forcefully as ever, in the book <strong>and</strong> in his<br />

work. Thous<strong>and</strong>s of people all over the world are being trained in<br />

Carnegie courses in increasing numbers each year. And other<br />

thous<strong>and</strong>s are reading <strong>and</strong> studying <strong>How</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Win</strong> <strong>Friends</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

lnfluence <strong>People</strong> <strong>and</strong> being inspired <strong>to</strong> use its principles <strong>to</strong> better<br />

their lives. To all of them, we offer this revision in the spirit of the<br />

honing <strong>and</strong> polishing of a finely made <strong>to</strong>ol.<br />

Dorothy Carnegie (Mrs. Dale Carnegie)<br />

--------------------------<br />

<strong>How</strong> This Book Was Written-And Why<br />

by<br />

Dale Carnegie<br />

During the first thirty-five years of the twentieth century, the<br />

publishing houses of America printed more than a fifth of a million<br />

different books. Most of them were deadly dull, <strong>and</strong> many were<br />

financial failures. "Many," did I say? The president of one of the<br />

largest publishing houses in the world confessed <strong>to</strong> me that his<br />

company, after seventy-five years of publishing experience, still lost<br />

money on seven out of every eight books it published.<br />

Why, then, did I have the temerity <strong>to</strong> write another book? And, after<br />

I had written it, why should you bother <strong>to</strong> read it?<br />

Fair questions, both; <strong>and</strong> I'll try <strong>to</strong> answer them.

I have, since 1912, been conducting educational courses for business<br />

<strong>and</strong> professional men <strong>and</strong> women in New York. At first, I conducted<br />

courses in public speaking only - courses designed <strong>to</strong> train adults, by<br />

actual experience, <strong>to</strong> think on their feet <strong>and</strong> express their ideas with<br />

more clarity, more effectiveness <strong>and</strong> more poise, both in business<br />

interviews <strong>and</strong> before groups.<br />

But gradually, as the seasons passed, I realized that as sorely as<br />

these adults needed training in effective speaking, they needed still<br />

more training in the fine art of getting along with people in everyday<br />

business <strong>and</strong> social contacts.<br />

I also gradually realized that I was sorely in need of such training<br />

myself. As I look back across the years, I am appalled at my own<br />

frequent lack of finesse <strong>and</strong> underst<strong>and</strong>ing. <strong>How</strong> I wish a book such<br />

as this had been placed in my h<strong>and</strong>s twenty years ago! What a<br />

priceless boon it would have been.<br />

Dealing with people is probably the biggest problem you face,<br />

especially if you are in business. Yes, <strong>and</strong> that is also true if you are<br />

a housewife, architect or engineer. Research done a few years ago<br />

under the auspices of the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement<br />

of Teaching uncovered a most important <strong>and</strong> significant fact - a fact<br />

later confirmed by additional studies made at the Carnegie Institute<br />

of Technology. These investigations revealed that even in such<br />

technical lines as engineering, about 15 percent of one's financial<br />

success is due <strong>to</strong> one's technical knowledge <strong>and</strong> about 85 percent is<br />

due <strong>to</strong> skill in human engineering-<strong>to</strong> personality <strong>and</strong> the ability <strong>to</strong><br />

lead people.<br />

For many years, I conducted courses each season at the Engineers'<br />

Club of Philadelphia, <strong>and</strong> also courses for the New York Chapter of<br />

the American Institute of Electrical Engineers. A <strong>to</strong>tal of probably<br />

more than fifteen hundred engineers have passed through my<br />

classes. They came <strong>to</strong> me because they had finally realized, after<br />

years of observation <strong>and</strong> experience, that the highest-paid personnel<br />

in engineering are frequently not those who know the most about<br />

engineering. One can for example, hire mere technical ability in<br />

engineering, accountancy, architecture or any other profession at<br />

nominal salaries. But the person who has technical knowledge plus<br />

the ability <strong>to</strong> express ideas, <strong>to</strong> assume leadership, <strong>and</strong> <strong>to</strong> arouse<br />

enthusiasm among people-that person is headed for higher earning<br />

power.<br />

In the heyday of his activity, John D. Rockefeller said that "the ability<br />

<strong>to</strong> deal with people is as purchasable a commodity as sugar or<br />

coffee." "And I will pay more for that ability," said John D., "than for<br />

any other under the sun."

Wouldn't you suppose that every college in the l<strong>and</strong> would conduct<br />

courses <strong>to</strong> develop the highest-priced ability under the sun? But if<br />

there is just one practical, common-sense course of that kind given<br />

for adults in even one college in the l<strong>and</strong>, it has escaped my<br />

attention up <strong>to</strong> the present writing.<br />

The University of Chicago <strong>and</strong> the United Y.M.C.A. Schools conducted<br />

a survey <strong>to</strong> determine what adults want <strong>to</strong> study.<br />

That survey cost $25,000 <strong>and</strong> <strong>to</strong>ok two years. The last part of the<br />

survey was made in Meriden, Connecticut. It had been chosen as a<br />

typical American <strong>to</strong>wn. Every adult in Meriden was interviewed <strong>and</strong><br />

requested <strong>to</strong> answer 156 questions-questions such as "What is your<br />

business or profession? Your education? <strong>How</strong> do you spend your<br />

spare time? What is your income? Your hobbies? Your ambitions?<br />

Your problems? What subjects are you most interested in studying?"<br />

And so on. That survey revealed that health is the prime interest of<br />

adults <strong>and</strong> that their second interest is people; how <strong>to</strong> underst<strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> get along with people; how <strong>to</strong> make people like you; <strong>and</strong> how <strong>to</strong><br />

win others <strong>to</strong> your way of thinking.<br />

So the committee conducting this survey resolved <strong>to</strong> conduct such a<br />

course for adults in Meriden. They searched diligently for a practical<br />

textbook on the subject <strong>and</strong> found-not one. Finally they approached<br />

one of the world's outst<strong>and</strong>ing authorities on adult education <strong>and</strong><br />

asked him if he knew of any book that met the needs of this group.<br />

"No," he replied, "I know what those adults want. But the book they<br />

need has never been written."<br />

I knew from experience that this statement was true, for I myself<br />

had been searching for years <strong>to</strong> discover a practical, working<br />

h<strong>and</strong>book on human relations.<br />

Since no such book existed, I have tried <strong>to</strong> write one for use in my<br />

own courses. And here it is. I hope you like it.<br />

In preparation for this book, I read everything that I could find on<br />

the subject- everything from newspaper columns, magazine articles,<br />

records of the family courts, the writings of the old philosophers <strong>and</strong><br />

the new psychologists. In addition, I hired a trained researcher <strong>to</strong><br />

spend one <strong>and</strong> a half years in various libraries reading everything I<br />

had missed, plowing through erudite <strong>to</strong>mes on psychology, poring<br />

over hundreds of magazine articles, searching through countless<br />

biographies, trying <strong>to</strong> ascertain how the great leaders of all ages had<br />

dealt with people. We read their biographies, We read the life s<strong>to</strong>ries<br />

of all great leaders from Julius Caesar <strong>to</strong> Thomas Edison. I recall that<br />

we read over one hundred biographies of Theodore Roosevelt alone.<br />

We were determined <strong>to</strong> spare no time, no expense, <strong>to</strong> discover every<br />

practical idea that anyone had ever used throughout the ages for<br />

winning friends <strong>and</strong> influencing people.

I personally interviewed scores of successful people, some of them<br />

world-famous-inven<strong>to</strong>rs like Marconi <strong>and</strong> Edison; political leaders like<br />

Franklin D. Roosevelt <strong>and</strong> James Farley; business leaders like Owen<br />

D. Young; movie stars like Clark Gable <strong>and</strong> Mary Pickford; <strong>and</strong><br />

explorers like Martin Johnson-<strong>and</strong> tried <strong>to</strong> discover the techniques<br />

they used in human relations.<br />

From all this material, I prepared a short talk. I called it "<strong>How</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Win</strong><br />

<strong>Friends</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Influence</strong> <strong>People</strong>." I say "short." It was short in the<br />

beginning, but it soon exp<strong>and</strong>ed <strong>to</strong> a lecture that consumed one<br />

hour <strong>and</strong> thirty minutes. For years, I gave this talk each season <strong>to</strong><br />

the adults in the Carnegie Institute courses in New York.<br />

I gave the talk <strong>and</strong> urged the listeners <strong>to</strong> go out <strong>and</strong> test it in their<br />

business <strong>and</strong> social contacts, <strong>and</strong> then come back <strong>to</strong> class <strong>and</strong> speak<br />

about their experiences <strong>and</strong> the results they had achieved. What an<br />

interesting assignment! These men <strong>and</strong> women, hungry for selfimprovement,<br />

were fascinated by the idea of working in a new kind<br />

of labora<strong>to</strong>ry - the first <strong>and</strong> only labora<strong>to</strong>ry of human relationships<br />

for adults that had ever existed.<br />

This book wasn't written in the usual sense of the word. It grew as a<br />

child grows. It grew <strong>and</strong> developed out of that labora<strong>to</strong>ry, out of the<br />

experiences of thous<strong>and</strong>s of adults.<br />

Years ago, we started with a set of rules printed on a card no larger<br />

than a postcard. The next season we printed a larger card, then a<br />

leaflet, then a series of booklets, each one exp<strong>and</strong>ing in size <strong>and</strong><br />

scope. After fifteen years of experiment <strong>and</strong> research came this<br />

book.<br />

The rules we have set down here are not mere theories or<br />

guesswork. They work like magic. Incredible as it sounds, I have<br />

seen the application of these principles literally revolutionize the lives<br />

of many people.<br />

To illustrate: A man with 314 employees joined one of these courses.<br />

For years, he had driven <strong>and</strong> criticized <strong>and</strong> condemned his<br />

employees without stint or discretion. Kindness, words of<br />

appreciation <strong>and</strong> encouragement were alien <strong>to</strong> his lips. After studying<br />

the principles discussed in this book, this employer sharply altered<br />

his philosophy of life. His organization is now inspired with a new<br />

loyalty, a new enthusiasm, a new spirit of team-work. Three hundred<br />

<strong>and</strong> fourteen enemies have been turned in<strong>to</strong> 314 friends. As he<br />

proudly said in a speech before the class: "When I used <strong>to</strong> walk<br />

through my establishment, no one greeted me. My employees<br />

actually looked the other way when they saw me approaching. But<br />

now they are all my friends <strong>and</strong> even the jani<strong>to</strong>r calls me by my first<br />

name."

This employer gained more profit, more leisure <strong>and</strong> -what is infinitely<br />

more important-he found far more happiness in his business <strong>and</strong> in<br />

his home.<br />

Countless numbers of salespeople have sharply increased their sales<br />

by the use of these principles. Many have opened up new accounts -<br />

accounts that they had formerly solicited in vain. Executives have<br />

been given increased authority, increased pay. One executive<br />

reported a large increase in salary because he applied these truths.<br />

Another, an executive in the Philadelphia Gas Works Company, was<br />

slated for demotion when he was sixty-five because of his<br />

belligerence, because of his inability <strong>to</strong> lead people skillfully. This<br />

training not only saved him from the demotion but brought him a<br />

promotion with increased pay.<br />

On innumerable occasions, spouses attending the banquet given at<br />

the end of the course have <strong>to</strong>ld me that their homes have been<br />

much happier since their husb<strong>and</strong>s or wives started this training.<br />

<strong>People</strong> are frequently as<strong>to</strong>nished at the new results they achieve. It<br />

all seems like magic. In some cases, in their enthusiasm, they have<br />

telephoned me at my home on Sundays because they couldn't wait<br />

forty-eight hours <strong>to</strong> report their achievements at the regular session<br />

of the course.<br />

One man was so stirred by a talk on these principles that he sat far<br />

in<strong>to</strong> the night discussing them with other members of the class. At<br />

three o'clock in the morning, the others went home. But he was so<br />

shaken by a realization of his own mistakes, so inspired by the vista<br />

of a new <strong>and</strong> richer world opening before him, that he was unable <strong>to</strong><br />

sleep. He didn't sleep that night or the next day or the next night.<br />

Who was he? A naive, untrained individual ready <strong>to</strong> gush over any<br />

new theory that came along? No, Far from it. He was a sophisticated,<br />

blasй dealer in art, very much the man about <strong>to</strong>wn, who spoke three<br />

languages fluently <strong>and</strong> was a graduate of two European universities.<br />

While writing this chapter, I received a letter from a German of the<br />

old school, an aris<strong>to</strong>crat whose forebears had served for generations<br />

as professional army officers under the Hohenzollerns. His letter,<br />

written from a transatlantic steamer, telling about the application of<br />

these principles, rose almost <strong>to</strong> a religious fervor.<br />

Another man, an old New Yorker, a Harvard graduate, a wealthy<br />

man, the owner of a large carpet fac<strong>to</strong>ry, declared he had learned<br />

more in fourteen weeks through this system of training about the<br />

fine art of influencing people than he had learned about the same<br />

subject during his four years in college. Absurd? Laughable?<br />

Fantastic? Of course, you are privileged <strong>to</strong> dismiss this statement

with whatever adjective you wish. I am merely reporting, without<br />

comment, a declaration made by a conservative <strong>and</strong> eminently<br />

successful Harvard graduate in a public address <strong>to</strong> approximately six<br />

hundred people at the Yale Club in New York on the evening of<br />

Thursday, February 23, 1933.<br />

"Compared <strong>to</strong> what we ought <strong>to</strong> be," said the famous Professor<br />

William James of Harvard, "compared <strong>to</strong> what we ought <strong>to</strong> be, we<br />

are only half awake. We are making use of only a small part of our<br />

physical <strong>and</strong> mental resources. Stating the thing broadly, the human<br />

individual thus lives far within his limits. He possesses powers of<br />

various sorts which he habitually fails <strong>to</strong> use,"<br />

Those powers which you "habitually fail <strong>to</strong> use"! The sole purpose of<br />

this book is <strong>to</strong> help you discover, develop <strong>and</strong> profit by those<br />

dormant <strong>and</strong> unused assets,<br />

"Education," said Dr. John G. Hibben, former president of Prince<strong>to</strong>n<br />

University, "is the ability <strong>to</strong> meet life's situations,"<br />

If by the time you have finished reading the first three chapters of<br />

this book- if you aren't then a little better equipped <strong>to</strong> meet life's<br />

situations, then I shall consider this book <strong>to</strong> be a <strong>to</strong>tal failure so far<br />

as you are concerned. For "the great aim of education," said Herbert<br />

Spencer, "is not knowledge but action."<br />

And this is an action book.<br />

DALE CARNEGIE 1936<br />

----------------------------------<br />

Nine Suggestions on <strong>How</strong> <strong>to</strong> Get the Most Out of This Book<br />

1. If you wish <strong>to</strong> get the most out of this book, there is one<br />

indispensable requirement, one essential infinitely more important<br />

than any rule or technique. Unless you have this one fundamental<br />

requisite, a thous<strong>and</strong> rules on how <strong>to</strong> study will avail little, And if you<br />

do have this cardinal endowment, then you can achieve wonders<br />

without reading any suggestions for getting the most out of a book.<br />

What is this magic requirement? Just this: a deep, driving desire <strong>to</strong><br />

learn, a vigorous determination <strong>to</strong> increase your ability <strong>to</strong> deal with<br />

people.<br />

<strong>How</strong> can you develop such an urge? By constantly reminding yourself<br />

how important these principles are <strong>to</strong> you. Picture <strong>to</strong> yourself how<br />

their mastery will aid you in leading a richer, fuller, happier <strong>and</strong> more<br />

fulfilling life. Say <strong>to</strong> yourself over <strong>and</strong> over: "My popularity, my

happiness <strong>and</strong> sense of worth depend <strong>to</strong> no small extent upon my<br />

skill in dealing with people."<br />

2. Read each chapter rapidly at first <strong>to</strong> get a bird's-eye view of it.<br />

You will probably be tempted then <strong>to</strong> rush on <strong>to</strong> the next one. But<br />

don't - unless you are reading merely for entertainment. But if you<br />

are reading because you want <strong>to</strong> increase your skill in human<br />

relations, then go back <strong>and</strong> reread each chapter thoroughly. In the<br />

long run, this will mean saving time <strong>and</strong> getting results.<br />

3. S<strong>to</strong>p frequently in your reading <strong>to</strong> think over what you are<br />

reading. Ask yourself just how <strong>and</strong> when you can apply each<br />

suggestion.<br />

4. Read with a crayon, pencil, pen, magic marker or highlighter in<br />

your h<strong>and</strong>. When you come across a suggestion that you feel you<br />

can use, draw a line beside it. If it is a four-star suggestion, then<br />

underscore every sentence or highlight it, or mark it with "****."<br />

Marking <strong>and</strong> underscoring a book makes it more interesting, <strong>and</strong> far<br />

easier <strong>to</strong> review rapidly.<br />

5. I knew a woman who had been office manager for a large<br />

insurance concern for fifteen years. Every month, she read all the<br />

insurance contracts her company had issued that month. Yes, she<br />

read many of the same contracts over month after month, year after<br />

year. Why? Because experience had taught her that that was the<br />

only way she could keep their provisions clearly in mind. I once spent<br />

almost two years writing a book on public speaking <strong>and</strong> yet I found I<br />

had <strong>to</strong> keep going back over it from time <strong>to</strong> time in order <strong>to</strong><br />

remember what I had written in my own book. The rapidity with<br />

which we forget is as<strong>to</strong>nishing.<br />

So, if you want <strong>to</strong> get a real, lasting benefit out of this book, don't<br />

imagine that skimming through it once will suffice. After reading it<br />

thoroughly, you ought <strong>to</strong> spend a few hours reviewing it every<br />

month, Keep it on your desk in front of you every day. Glance<br />

through it often. Keep constantly impressing yourself with the rich<br />

possibilities for improvement that still lie in the offing. Remember<br />

that the use of these principles can be made habitual only by a<br />

constant <strong>and</strong> vigorous campaign of review <strong>and</strong> application. There is<br />

no other way.<br />

6. Bernard Shaw once remarked: "If you teach a man anything, he<br />

will never learn." Shaw was right. Learning is an active process. We<br />

learn by doing. So, if you desire <strong>to</strong> master the principles you are<br />

studying in this book, do something about them. Apply these rules at<br />

every opportunity. If you don't you will forget them quickly. Only<br />

knowledge that is used sticks in your mind.

You will probably find it difficult <strong>to</strong> apply these suggestions all the<br />

time. I know because I wrote the book, <strong>and</strong> yet frequently I found it<br />

difficult <strong>to</strong> apply everything I advocated. For example, when you are<br />

displeased, it is much easier <strong>to</strong> criticize <strong>and</strong> condemn than it is <strong>to</strong> try<br />

<strong>to</strong> underst<strong>and</strong> the other person's viewpoint. It is frequently easier <strong>to</strong><br />

find fault than <strong>to</strong> find praise. It is more natural <strong>to</strong> talk about what<br />

vou want than <strong>to</strong> talk about what the other person wants. And so on,<br />

So, as you read this book, remember that you are not merely trying<br />

<strong>to</strong> acquire information. You are attempting <strong>to</strong> form new habits. Ah<br />

yes, you are attempting a new way of life. That will require time <strong>and</strong><br />

persistence <strong>and</strong> daily application.<br />

So refer <strong>to</strong> these pages often. Regard this as a working h<strong>and</strong>book on<br />

human relations; <strong>and</strong> whenever you are confronted with some<br />

specific problem - such as h<strong>and</strong>ling a child, winning your spouse <strong>to</strong><br />

your way of thinking, or satisfying an irritated cus<strong>to</strong>mer - hesitate<br />

about doing the natural thing, the impulsive thing. This is usually<br />

wrong. Instead, turn <strong>to</strong> these pages <strong>and</strong> review the paragraphs you<br />

have underscored. Then try these new ways <strong>and</strong> watch them achieve<br />

magic for you.<br />

7. Offer your spouse, your child or some business associate a dime<br />

or a dollar every time he or she catches you violating a certain<br />

principle. Make a lively game out of mastering these rules.<br />

8. The president of an important Wall Street bank once described, in<br />

a talk before one of my classes, a highly efficient system he used for<br />

self-improvement. This man had little formal schooling; yet he had<br />

become one of the most important financiers in America, <strong>and</strong> he<br />

confessed that he owed most of his success <strong>to</strong> the constant<br />

application of his homemade system. This is what he does, I'll put it<br />

in his own words as accurately as I can remember.<br />

"For years I have kept an engagement book showing all the<br />

appointments I had during the day. My family never made any plans<br />

for me on Saturday night, for the family knew that I devoted a part<br />

of each Saturday evening <strong>to</strong> the illuminating process of selfexamination<br />

<strong>and</strong> review <strong>and</strong> appraisal. After dinner I went off by<br />

myself, opened my engagement book, <strong>and</strong> thought over all the<br />

interviews, discussions <strong>and</strong> meetings that had taken place during the<br />

week. I asked myself:<br />

'What mistakes did I make that time?' 'What did I do that was right<strong>and</strong><br />

in what way could I have improved my performance?' 'What<br />

lessons can I learn from that experience?'<br />

"I often found that this weekly review made me very unhappy. I was<br />

frequently as<strong>to</strong>nished at my own blunders. Of course, as the years<br />

passed, these blunders became less frequent. Sometimes I was<br />

inclined <strong>to</strong> pat myself on the back a little after one of these sessions.

This system of self-analysis, self-education, continued year after<br />

year, did more for me than any other one thing I have ever<br />

attempted.<br />

"It helped me improve my ability <strong>to</strong> make decisions - <strong>and</strong> it aided me<br />

enormously in all my contacts with people. I cannot recommend it<br />

<strong>to</strong>o highly."<br />

Why not use a similar system <strong>to</strong> check up on your application of the<br />

principles discussed in this book? If you do, two things will result.<br />

First, you will find yourself engaged in an educational process that is<br />

both intriguing <strong>and</strong> priceless.<br />

Second, you will find that your ability <strong>to</strong> meet <strong>and</strong> deal with people<br />

will grow enormously.<br />

9. You will find at the end of this book several blank pages on which<br />

you should record your triumphs in the application of these<br />

principles. Be specific. Give names, dates, results. Keeping such a<br />

record will inspire you <strong>to</strong> greater efforts; <strong>and</strong> how fascinating these<br />

entries will be when you chance upon them some evening years from<br />

now!<br />

In order <strong>to</strong> get the most out of this book:<br />

• a. Develop a deep, driving desire <strong>to</strong> master the principles of human<br />

relations,<br />

• b. Read each chapter twice before going on <strong>to</strong> the next one.<br />

• c. As you read, s<strong>to</strong>p frequently <strong>to</strong> ask yourself how you can apply<br />

each suggestion.<br />

• d. Underscore each important idea.<br />

• e. Review this book each month.<br />

• f. Apply these principles at every opportunity. Use this volume as a<br />

working h<strong>and</strong>book <strong>to</strong> help you solve your daily problems.<br />

• g. Make a lively game out of your learning by offering some friend<br />

a dime or a dollar every time he or she catches you violating one of<br />

these principles.<br />

• h. Check up each week on the progress you are mak-ing. Ask<br />

yourself what mistakes you have made, what improvement, what<br />

lessons you have learned for the future.<br />

• i. Keep notes in the back of this book showing how <strong>and</strong> when you<br />

have applied these principles.<br />

------------------------------<br />

A Shortcut <strong>to</strong> Distinction<br />

by Lowell Thomas

This biographical information about Dale Carnegie was written as an<br />

introduction <strong>to</strong> the original edition of <strong>How</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Win</strong> <strong>Friends</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>Influence</strong> <strong>People</strong>. It is reprinted in this edition <strong>to</strong> give the readers<br />

additional background on Dale Carnegie.<br />

It was a cold January night in 1935, but the weather couldn't keep<br />

them away. Two thous<strong>and</strong> five hundred men <strong>and</strong> women thronged<br />

in<strong>to</strong> the gr<strong>and</strong> ballroom of the Hotel Pennsylvania in New York. Every<br />

available seat was filled by half-past seven. At eight o'clock, the<br />

eager crowd was still pouring in. The spacious balcony was soon<br />

jammed. Presently even st<strong>and</strong>ing space was at a premium, <strong>and</strong><br />

hundreds of people, tired after navigating a day in business, s<strong>to</strong>od<br />

up for an hour <strong>and</strong> a half that night <strong>to</strong> witness - what?<br />

A fashion show?<br />

A six-day bicycle race or a personal appearance by Clark Gable?<br />

No. These people had been lured there by a newspaper ad. Two<br />

evenings previously, they had seen this full-page announcement in<br />

the New York Sun staring them in the face:<br />

Learn <strong>to</strong> Speak Effectively Prepare for Leadership<br />

Old stuff? Yes, but believe it or not, in the most sophisticated <strong>to</strong>wn<br />

on earth, during a depression with 20 percent of the population on<br />

relief, twenty-five hundred people had left their homes <strong>and</strong> hustled<br />

<strong>to</strong> the hotel in response <strong>to</strong> that ad.<br />

The people who responded were of the upper economic strata -<br />

executives, employers <strong>and</strong> professionals.<br />

These men <strong>and</strong> women had come <strong>to</strong> hear the opening gun of an<br />

ultramodern, ultrapractical course in "Effective Speaking <strong>and</strong><br />

Influencing Men in Business"- a course given by the Dale Carnegie<br />

Institute of Effective Speaking <strong>and</strong> Human Relations.<br />

Why were they there, these twenty-five hundred business men <strong>and</strong><br />

women?<br />

Because of a sudden hunger for more education because of the<br />

depression?<br />

Apparently not, for this same course had been playing <strong>to</strong> packed<br />

houses in New York City every season for the preceding twenty-four<br />

years. During that time, more than fifteen thous<strong>and</strong> business <strong>and</strong><br />

professional people had been trained by Dale Carnegie. Even large,<br />

skeptical, conservative organizations such as the Westinghouse

Electric Company, the McGraw-Hill Publishing Company, the Brooklyn<br />

Union Gas Company, the Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce, the<br />

American Institute of Electrical Engineers <strong>and</strong> the New York<br />

Telephone Company have had this training conducted in their own<br />

offices for the benefit of their members <strong>and</strong> executives.<br />

The fact that these people, ten or twenty years after leaving grade<br />

school, high school or college, come <strong>and</strong> take this training is a<br />

glaring commentary on the shocking deficiencies of our educational<br />

system.<br />

What do adults really want <strong>to</strong> study? That is an important question;<br />

<strong>and</strong> in order <strong>to</strong> answer it, the University of Chicago, the American<br />

Association for Adult Education, <strong>and</strong> the United Y.M.C.A. Schools<br />

made a survey over a two-year period.<br />

That survey revealed that the prime interest of adults is health. It<br />

also revealed that their second interest is in developing skill in<br />

human relationships - they want <strong>to</strong> learn the technique of getting<br />

along with <strong>and</strong> influencing other people. They don't want <strong>to</strong> become<br />

public speakers, <strong>and</strong> they don't want <strong>to</strong> listen <strong>to</strong> a lot of high<br />

sounding talk about psychology; they want suggestions they can use<br />

immediately in business, in social contacts <strong>and</strong> in the home.<br />

So that was what adults wanted <strong>to</strong> study, was it?<br />

"All right," said the people making the survey. "Fine. If that is what<br />

they want, we'll give it <strong>to</strong> them."<br />

Looking around for a textbook, they discovered that no working<br />

manual had ever been written <strong>to</strong> help people solve their daily<br />

problems in human relationships.<br />

Here was a fine kettle of fish! For hundreds of years, learned<br />

volumes had been written on Greek <strong>and</strong> Latin <strong>and</strong> higher<br />

mathematics - <strong>to</strong>pics about which the average adult doesn't give two<br />

hoots. But on the one subject on which he has a thirst for<br />

knowledge, a veritable passion for guidance <strong>and</strong> help - nothing!<br />

This explained the presence of twenty-five hundred eager adults<br />

crowding in<strong>to</strong> the gr<strong>and</strong> ballroom of the Hotel Pennsylvania in<br />

response <strong>to</strong> a newspaper advertisement. Here, apparently, at last<br />

was the thing for which they had long been seeking.<br />

Back in high school <strong>and</strong> college, they had pored over books,<br />

believing that knowledge alone was the open sesame <strong>to</strong> financial -<br />

<strong>and</strong> professional rewards.<br />

But a few years in the rough-<strong>and</strong>-tumble of business <strong>and</strong><br />

professional life had brought sharp dissillusionment. They had seen

some of the most important business successes won by men who<br />

possessed, in addition <strong>to</strong> their knowledge, the ability <strong>to</strong> talk well, <strong>to</strong><br />

win people <strong>to</strong> their way of thinking, <strong>and</strong> <strong>to</strong> "sell" themselves <strong>and</strong><br />

their ideas.<br />

They soon discovered that if one aspired <strong>to</strong> wear the captain's cap<br />

<strong>and</strong> navigate the ship of business, personality <strong>and</strong> the ability <strong>to</strong> talk<br />

are more important than a knowledge of Latin verbs or a sheepskin<br />

from Harvard.<br />

The advertisement in the New York Sun promised that the meeting<br />

would be highly entertaining. It was. Eighteen people who had taken<br />

the course were marshaled in front of the loudspeaker - <strong>and</strong> fifteen<br />

of them were given precisely seventy-five seconds each <strong>to</strong> tell his or<br />

her s<strong>to</strong>ry. Only seventy-five seconds of talk, then "bang" went the<br />

gavel, <strong>and</strong> the chairman shouted, "Time! Next speaker!"<br />

The affair moved with the speed of a herd of buffalo thundering<br />

across the plains. Specta<strong>to</strong>rs s<strong>to</strong>od for an hour <strong>and</strong> a half <strong>to</strong> watch<br />

the performance.<br />

The speakers were a cross section of life: several sales<br />

representatives, a chain s<strong>to</strong>re executive, a baker, the president of a<br />

trade association, two bankers, an insurance agent, an accountant, a<br />

dentist, an architect, a druggist who had come from Indianapolis <strong>to</strong><br />

New York <strong>to</strong> take the course, a lawyer who had come from Havana<br />

in order <strong>to</strong> prepare himself <strong>to</strong> give one important three-minute<br />

speech.<br />

The first speaker bore the Gaelic name Patrick J. O'Haire. Born in<br />

Irel<strong>and</strong>, he attended school for only four years, drifted <strong>to</strong> America,<br />

worked as a mechanic, then as a chauffeur.<br />

Now, however, he was forty, he had a growing family <strong>and</strong> needed<br />

more money, so he tried selling trucks. Suffering from an inferiority<br />

complex that, as he put it, was eating his heart out, he had <strong>to</strong> walk<br />

up <strong>and</strong> down in front of an office half a dozen times before he could<br />

summon up enough courage <strong>to</strong> open the door. He was so<br />

discouraged as a salesman that he was thinking of going back <strong>to</strong><br />

working with his h<strong>and</strong>s in a machine shop, when one day he<br />

received a letter inviting him <strong>to</strong> an organization meeting of the Dale<br />

Carnegie Course in Effective Speaking.<br />

He didn't want <strong>to</strong> attend. He feared he would have <strong>to</strong> associate with<br />

a lot of college graduates, that he would be out of place.<br />

His despairing wife insisted that he go, saying, "It may do you some<br />

good, Pat. God knows you need it." He went down <strong>to</strong> the place<br />

where the meeting was <strong>to</strong> be held <strong>and</strong> s<strong>to</strong>od on the sidewalk for five

minutes before he could generate enough self-confidence <strong>to</strong> enter<br />

the room.<br />

The first few times he tried <strong>to</strong> speak in front of the others, he was<br />

dizzy with fear. But as the weeks drifted by, he lost all fear of<br />

audiences <strong>and</strong> soon found that he loved <strong>to</strong> talk - the bigger the<br />

crowd, the better. And he also lost his fear of individuals <strong>and</strong> of his<br />

superiors. He presented his ideas <strong>to</strong> them, <strong>and</strong> soon he had been<br />

advanced in<strong>to</strong> the sales department. He had become a valued <strong>and</strong><br />

much liked member of his company. This night, in the Hotel<br />

Pennsylvania, Patrick O'Haire s<strong>to</strong>od in front of twenty-five hundred<br />

people <strong>and</strong> <strong>to</strong>ld a gay, rollicking s<strong>to</strong>ry of his achievements. Wave<br />

after wave of laughter swept over the audience. Few professional<br />

speakers could have equaled his performance.<br />

The next speaker, Godfrey Meyer, was a gray-headed banker, the<br />

father of eleven children. The first time he had attempted <strong>to</strong> speak in<br />

class, he was literally struck dumb. His mind refused <strong>to</strong> function. His<br />

s<strong>to</strong>ry is a vivid illustration of how leadership gravitates <strong>to</strong> the person<br />

who can talk.<br />

He worked on Wall Street, <strong>and</strong> for twenty-five years he had been<br />

living in Clif<strong>to</strong>n, New Jersey. During that time, he had taken no<br />

active part in community affairs <strong>and</strong> knew perhaps five hundred<br />

people.<br />

Shortly after he had enrolled in the Carnegie course, he received his<br />

tax bill <strong>and</strong> was infuriated by what he considered unjust charges.<br />

Ordinarily, he would have sat at home <strong>and</strong> fumed, or he would have<br />

taken it out in grousing <strong>to</strong> his neighbors. But instead, he put on his<br />

hat that night, walked in<strong>to</strong> the <strong>to</strong>wn meeting, <strong>and</strong> blew off steam in<br />

public.<br />

As a result of that talk of indignation, the citizens of Clif<strong>to</strong>n, New<br />

Jersey, urged him <strong>to</strong> run for the <strong>to</strong>wn council. So for weeks he went<br />

from one meeting <strong>to</strong> another, denouncing waste <strong>and</strong> municipal<br />

extravagance.<br />

There were ninety-six c<strong>and</strong>idates in the field. When the ballots were<br />

counted, lo, Godfrey Meyer's name led all the rest. Almost overnight,<br />

he had become a public figure among the forty thous<strong>and</strong> people in<br />

his community. As a result of his talks, he made eighty times more<br />

friends in six weeks than he had been able <strong>to</strong> previously in twentyfive<br />

years.<br />

And his salary as councilman meant that he got a return of 1,000<br />

percent a year on his investment in the Carnegie course.

The third speaker, the head of a large national association of food<br />

manufacturers, <strong>to</strong>ld how he had been unable <strong>to</strong> st<strong>and</strong> up <strong>and</strong><br />

express his ideas at meetings of a board of direc<strong>to</strong>rs.<br />

As a result of learning <strong>to</strong> think on his feet, two as<strong>to</strong>nishing things<br />

happened. He was soon made president of his association, <strong>and</strong> in<br />

that capacity, he was obliged <strong>to</strong> address meetings all over the United<br />

States. Excerpts from his talks were put on the Associated Press<br />

wires <strong>and</strong> printed in newspapers <strong>and</strong> trade magazines throughout<br />

the country.<br />

In two years, after learning <strong>to</strong> speak more effectively, he received<br />

more free publicity for his company <strong>and</strong> its products than he had<br />

been able <strong>to</strong> get previously with a quarter of a million dollars spent<br />

in direct advertising. This speaker admitted that he had formerly<br />

hesitated <strong>to</strong> telephone some of the more important business<br />

executives in Manhattan <strong>and</strong> invite them <strong>to</strong> lunch with him. But as a<br />

result of the prestige he had acquired by his talks, these same<br />

people telephoned him <strong>and</strong> invited him <strong>to</strong> lunch <strong>and</strong> apologized <strong>to</strong><br />

him for encroaching on his time.<br />

The ability <strong>to</strong> speak is a shortcut <strong>to</strong> distinction. It puts a person in<br />

the limelight, raises one head <strong>and</strong> shoulders above the crowd. And<br />

the person who can speak acceptably is usually given credit for an<br />

ability out of all proportion <strong>to</strong> what he or she really possesses.<br />

A movement for adult education has been sweeping over the nation;<br />

<strong>and</strong> the most spectacular force in that movement was Dale Carnegie,<br />

a man who listened <strong>to</strong> <strong>and</strong> critiqued more talks by adults than has<br />

any other man in captivity. According <strong>to</strong> a car<strong>to</strong>on by "Believe-It-or-<br />

Not" Ripley, he had criticized 150,000 speeches. If that gr<strong>and</strong> <strong>to</strong>tal<br />

doesn't impress you, remember that it meant one talk for almost<br />

every day that has passed since Columbus discovered America. Or,<br />

<strong>to</strong> put it in other words, if all the people who had spoken before him<br />

had used only three minutes <strong>and</strong> had appeared before him in<br />

succession, it would have taken ten months, listening day <strong>and</strong> night,<br />

<strong>to</strong> hear them all.<br />

Dale Carnegie's own career, filled with sharp contrasts, was a striking<br />

example of what a person can accomplish when obsessed with an<br />

original idea <strong>and</strong> afire with enthusiasm.<br />

Born on a Missouri farm ten miles from a railway, he never saw a<br />

streetcar until he was twelve years old; yet by the time he was fortysix,<br />

he was familiar with the far-flung corners of the earth,<br />

everywhere from Hong Kong <strong>to</strong> Hammerfest; <strong>and</strong>, at one time, he<br />

approached closer <strong>to</strong> the North Pole than Admiral Byrd's<br />

headquarters at Little America was <strong>to</strong> the South Pole.

This Missouri lad who had once picked strawberries <strong>and</strong> cut<br />

cockleburs for five cents an hour became the highly paid trainer of<br />

the executives of large corporations in the art of self-expression.<br />

This erstwhile cowboy who had once punched cattle <strong>and</strong> br<strong>and</strong>ed<br />

calves <strong>and</strong> ridden fences out in western South Dakota later went <strong>to</strong><br />

London <strong>to</strong> put on shows under the patronage of the royal family.<br />

This chap who was a <strong>to</strong>tal failure the first half-dozen times he tried<br />

<strong>to</strong> speak in public later became my personal manager. Much of my<br />

success has been due <strong>to</strong> training under Dale Carnegie.<br />

Young Carnegie had <strong>to</strong> struggle for an education, for hard luck was<br />

always battering away at the old farm in northwest Missouri with a<br />

flying tackle <strong>and</strong> a body slam. Year after year, the "102" River rose<br />

<strong>and</strong> drowned the corn <strong>and</strong> swept away the hay. Season after season,<br />

the fat hogs sickened <strong>and</strong> died from cholera, the bot<strong>to</strong>m fell out of<br />

the market for cattle <strong>and</strong> mules, <strong>and</strong> the bank threatened <strong>to</strong><br />

foreclose the mortgage.<br />

Sick with discouragement, the family sold out <strong>and</strong> bought another<br />

farm near the State Teachers' College at Warrensburg, Missouri.<br />

Board <strong>and</strong> room could be had in <strong>to</strong>wn for a dollar a day, but young<br />

Carnegie couldn't afford it. So he stayed on the farm <strong>and</strong> commuted<br />

on horseback three miles <strong>to</strong> college each day. At home, he milked<br />

the cows, cut the wood, fed the hogs, <strong>and</strong> studied his Latin verbs by<br />

the light of a coal-oil lamp until his eyes blurred <strong>and</strong> he began <strong>to</strong><br />

nod.<br />

Even when he got <strong>to</strong> bed at midnight, he set the alarm for three<br />

o'clock. His father bred pedigreed Duroc-Jersey hogs - <strong>and</strong> there was<br />

danger, during the bitter cold nights, that the young pigs would<br />

freeze <strong>to</strong> death; so they were put in a basket, covered with a gunny<br />

sack, <strong>and</strong> set behind the kitchen s<strong>to</strong>ve. True <strong>to</strong> their nature, the pigs<br />

dem<strong>and</strong>ed a hot meal at 3 A.M. So when the alarm went off, Dale<br />

Carnegie crawled out of the blankets, <strong>to</strong>ok the basket of pigs out <strong>to</strong><br />

their mother, waited for them <strong>to</strong> nurse, <strong>and</strong> then brought them back<br />

<strong>to</strong> the warmth of the kitchen s<strong>to</strong>ve.<br />

There were six hundred students in State Teachers' College, <strong>and</strong><br />

Dale Carnegie was one of the isolated half-dozen who couldn't afford<br />

<strong>to</strong> board in <strong>to</strong>wn. He was ashamed of the poverty that made it<br />

necessary for him <strong>to</strong> ride back <strong>to</strong> the farm <strong>and</strong> milk the cows every<br />

night. He was ashamed of his coat, which was <strong>to</strong>o tight, <strong>and</strong> his<br />

trousers, which were <strong>to</strong>o short. Rapidly developing an inferiority<br />

complex, he looked about for some shortcut <strong>to</strong> distinction. He soon<br />

saw that there were certain groups in college that enjoyed influence<br />

<strong>and</strong> prestige - the football <strong>and</strong> baseball players <strong>and</strong> the chaps who<br />

won the debating <strong>and</strong> public-speaking contests.

Realizing that he had no flair for athletics, he decided <strong>to</strong> win one of<br />

the speaking contests. He spent months preparing his talks. He<br />

practiced as he sat in the saddle galloping <strong>to</strong> college <strong>and</strong> back; he<br />

practiced his speeches as he milked the cows; <strong>and</strong> then he mounted<br />

a bale of hay in the barn <strong>and</strong> with great gus<strong>to</strong> <strong>and</strong> gestures<br />

harangued the frightened pigeons about the issues of the day.<br />

But in spite of all his earnestness <strong>and</strong> preparation, he met with<br />

defeat after defeat. He was eighteen at the time - sensitive <strong>and</strong><br />

proud. He became so discouraged, so depressed, that he even<br />

thought of suicide. And then suddenly he began <strong>to</strong> win, not one<br />

contest, but every speaking contest in college.<br />

Other students pleaded with him <strong>to</strong> train them; <strong>and</strong> they won also.<br />

After graduating from college, he started selling correspondence<br />

courses <strong>to</strong> the ranchers among the s<strong>and</strong> hills of western Nebraska<br />

<strong>and</strong> eastern Wyoming. In spite of all his boundless energy <strong>and</strong><br />

enthusiasm, he couldn't make the grade. He became so discouraged<br />

that he went <strong>to</strong> his hotel room in Alliance, Nebraska, in the middle of<br />

the day, threw himself across the bed, <strong>and</strong> wept in despair. He<br />

longed <strong>to</strong> go back <strong>to</strong> college, he longed <strong>to</strong> retreat from the harsh<br />

battle of life; but he couldn't. So he resolved <strong>to</strong> go <strong>to</strong> Omaha <strong>and</strong> get<br />

another job. He didn't have the money for a railroad ticket, so he<br />

traveled on a freight train, feeding <strong>and</strong> watering two carloads of wild<br />

horses in return for his passage, After l<strong>and</strong>ing in south Omaha, he<br />

got a job selling bacon <strong>and</strong> soap <strong>and</strong> lard for Armour <strong>and</strong> Company.<br />

His terri<strong>to</strong>ry was up among the Badl<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong> the cow <strong>and</strong> Indian<br />

country of western South Dakota. He covered his terri<strong>to</strong>ry by freight<br />

train <strong>and</strong> stage coach <strong>and</strong> horseback <strong>and</strong> slept in pioneer hotels<br />

where the only partition between the rooms was a sheet of muslin.<br />

He studied books on salesmanship, rode bucking bronchos, played<br />

poker with the Indians, <strong>and</strong> learned how <strong>to</strong> collect money. And<br />

when, for example, an inl<strong>and</strong> s<strong>to</strong>rekeeper couldn't pay cash for the<br />

bacon <strong>and</strong> hams he had ordered, Dale Carnegie would take a dozen<br />

pairs of shoes off his shelf, sell the shoes <strong>to</strong> the railroad men, <strong>and</strong><br />

forward the receipts <strong>to</strong> Armour <strong>and</strong> Company.<br />

He would often ride a freight train a hundred miles a day. When the<br />

train s<strong>to</strong>pped <strong>to</strong> unload freight, he would dash up<strong>to</strong>wn, see three or<br />

four merchants, get his orders; <strong>and</strong> when the whistle blew, he would<br />

dash down the street again lickety-split <strong>and</strong> swing on<strong>to</strong> the train<br />

while it was moving.<br />

Within two years, he had taken an unproductive terri<strong>to</strong>ry that had<br />

s<strong>to</strong>od in the twenty-fifth place <strong>and</strong> had boosted it <strong>to</strong> first place<br />

among all the twenty-nine car routes leading out of south Omaha.<br />

Armour <strong>and</strong> Company offered <strong>to</strong> promote him, saying: "You have<br />

achieved what seemed impossible." But he refused the promotion<br />

<strong>and</strong> resigned, went <strong>to</strong> New York, studied at the American Academy

of Dramatic Arts, <strong>and</strong> <strong>to</strong>ured the country, playing the role of Dr.<br />

Hartley in Polly of the Circus.<br />

He would never be a Booth or a Barrymore. He had the good sense<br />

<strong>to</strong> recognize that, So back he went <strong>to</strong> sales work, selling au<strong>to</strong>mobiles<br />

<strong>and</strong> trucks for the Packard Mo<strong>to</strong>r Car Company.<br />

He knew nothing about machinery <strong>and</strong> cared nothing about it.<br />

Dreadfully unhappy, he had <strong>to</strong> scourge himself <strong>to</strong> his task each day.<br />

He longed <strong>to</strong> have time <strong>to</strong> study, <strong>to</strong> write the books he had dreamed<br />

about writing back in college. So he resigned. He was going <strong>to</strong> spend<br />

his days writing s<strong>to</strong>ries <strong>and</strong> novels <strong>and</strong> support himself by teaching<br />

in a night school.<br />

Teaching what? As he looked back <strong>and</strong> evaluated his college work,<br />

he saw that his training in public speaking had done more <strong>to</strong> give<br />

him confidence, courage, poise <strong>and</strong> the ability <strong>to</strong> meet <strong>and</strong> deal with<br />

people in business than had all the rest of his college courses put<br />

<strong>to</strong>gether, So he urged the Y.M.C.A. schools in New York <strong>to</strong> give him<br />

a chance <strong>to</strong> conduct courses in public speaking for people in<br />

business.<br />

What? Make ora<strong>to</strong>rs out of business people? Absurd. The Y.M.C.A.<br />

people knew. They had tried such courses -<strong>and</strong> they had always<br />

failed. When they refused <strong>to</strong> pay him a salary of two dollars a night,<br />

he agreed <strong>to</strong> teach on a commission basis <strong>and</strong> take a percentage of<br />

the net profits -if there were any profits <strong>to</strong> take. And inside of three<br />

years they were paying him thirty dollars a night on that basis -<br />

instead of two.<br />

The course grew. Other "Ys" heard of it, then other cities. Dale<br />

Carnegie soon became a glorified circuit rider covering New York,<br />

Philadelphia, Baltimore <strong>and</strong> later London <strong>and</strong> Paris. All the textbooks<br />

were <strong>to</strong>o academic <strong>and</strong> impractical for the business people who<br />

flocked <strong>to</strong> his courses. Because of this he wrote his own book<br />

entitled Public Speaking <strong>and</strong> Influencing Men in Business. It became<br />

the official text of all the Y.M.C.A.s as well as of the American<br />

Bankers' Association <strong>and</strong> the National Credit Men's Association.<br />

Dale Carnegie claimed that all people can talk when they get mad.<br />

He said that if you hit the most ignorant man in <strong>to</strong>wn on the jaw <strong>and</strong><br />

knock him down, he would get on his feet <strong>and</strong> talk with an<br />

eloquence, heat <strong>and</strong> emphasis that would have rivaled that world<br />

famous ora<strong>to</strong>r William Jennings Bryan at the height of his career. He<br />

claimed that almost any person can speak acceptably in public if he<br />

or she has self-confidence <strong>and</strong> an idea that is boiling <strong>and</strong> stewing<br />

within.<br />

The way <strong>to</strong> develop self-confidence, he said, is <strong>to</strong> do the thing you<br />

fear <strong>to</strong> do <strong>and</strong> get a record of successful experiences behind you. So

he forced each class member <strong>to</strong> talk at every session of the course.<br />

The audience is sympathetic. They are all in the same boat; <strong>and</strong>, by<br />

constant practice, they develop a courage, confidence <strong>and</strong><br />

enthusiasm that carry over in<strong>to</strong> their private speaking.<br />

Dale Carnegie would tell you that he made a living all these years,<br />

not by teaching public speaking - that was incidental. His main job<br />

was <strong>to</strong> help people conquer their fears <strong>and</strong> develop courage.<br />

He started out at first <strong>to</strong> conduct merely a course in public speaking,<br />

but the students who came were business men <strong>and</strong> women. Many of<br />

them hadn't seen the inside of a classroom in thirty years. Most of<br />

them were paying their tuition on the installment plan. They wanted<br />

results <strong>and</strong> they wanted them quick - results that they could use the<br />

next day in business interviews <strong>and</strong> in speaking before groups.<br />

So he was forced <strong>to</strong> be swift <strong>and</strong> practical. Consequently, he<br />

developed a system of training that is unique - a striking combination<br />

of public speaking, salesmanship, human relations <strong>and</strong> applied<br />

psychology.<br />

A slave <strong>to</strong> no hard-<strong>and</strong>-fast rules, he developed a course that is as<br />

real as the measles <strong>and</strong> twice as much fun.<br />

When the classes terminated, the graduates formed clubs of their<br />

own <strong>and</strong> continued <strong>to</strong> meet fortnightly for years afterward. One<br />

group of nineteen in Philadelphia met twice a month during the<br />

winter season for seventeen years. Class members frequently travel<br />

fifty or a hundred miles <strong>to</strong> attend classes. One student used <strong>to</strong><br />

commute each week from Chicago <strong>to</strong> New York. Professor William<br />

James of Harvard used <strong>to</strong> say that the average person develops only<br />

10 percent of his latent mental ability. Dale Carnegie, by helping<br />

business men <strong>and</strong> women <strong>to</strong> develop their latent possibilities,<br />

created one of the most significant movements in adult education<br />

LOWELL THOMAS 1936<br />

------------------------------<br />

Part One - Fundamental Techniques In H<strong>and</strong>ling <strong>People</strong><br />

1 "If You Want To Gather Honey, Don't Kick Over The Beehive"<br />

On May 7, 1931, the most sensational manhunt New York City had<br />

ever known had come <strong>to</strong> its climax. After weeks of search, "Two<br />

Gun" Crowley - the killer, the gunman who didn't smoke or drink -<br />

was at bay, trapped in his sweetheart's apartment on West End<br />

Avenue.

One hundred <strong>and</strong> fifty policemen <strong>and</strong> detectives laid siege <strong>to</strong> his <strong>to</strong>pfloor<br />

hideway. They chopped holes in the roof; they tried <strong>to</strong> smoke<br />

out Crowley, the "cop killer," with teargas. Then they mounted their<br />

machine guns on surrounding buildings, <strong>and</strong> for more than an hour<br />

one of New York's fine residential areas reverberated with the crack<br />

of pis<strong>to</strong>l fire <strong>and</strong> the rut-tat-tat of machine guns. Crowley, crouching<br />

behind an over-stuffed chair, fired incessantly at the police. Ten<br />

thous<strong>and</strong> excited people watched the battle. Nothing like it ever<br />

been seen before on the sidewalks of New York.<br />

When Crowley was captured, Police Commissioner E. P. Mulrooney<br />

declared that the two-gun desperado was one of the most dangerous<br />

criminals ever encountered in the his<strong>to</strong>ry of New York. "He will kill,"<br />

said the Commissioner, "at the drop of a feather."<br />

But how did "Two Gun" Crowley regard himself? We know, because<br />

while the police were firing in<strong>to</strong> his apartment, he wrote a letter<br />

addressed "To whom it may concern, " And, as he wrote, the blood<br />

flowing from his wounds left a crimson trail on the paper. In this<br />

letter Crowley said: "Under my coat is a weary heart, but a kind one<br />

- one that would do nobody any harm."<br />

A short time before this, Crowley had been having a necking party<br />

with his girl friend on a country road out on Long Isl<strong>and</strong>. Suddenly a<br />

policeman walked up <strong>to</strong> the car <strong>and</strong> said: "Let me see your license."<br />

Without saying a word, Crowley drew his gun <strong>and</strong> cut the policeman<br />

down with a shower of lead. As the dying officer fell, Crowley leaped<br />

out of the car, grabbed the officer's revolver, <strong>and</strong> fired another bullet<br />

in<strong>to</strong> the prostrate body. And that was the killer who said: "Under my<br />

coat is a weary heart, but a kind one - one that would do nobody<br />

any harm.'<br />

Crowley was sentenced <strong>to</strong> the electric chair. When he arrived at the<br />

death house in Sing Sing, did he say, "This is what I get for killing<br />

people"? No, he said: "This is what I get for defending myself."<br />

The point of the s<strong>to</strong>ry is this: "Two Gun" Crowley didn't blame<br />

himself for anything.<br />

Is that an unusual attitude among criminals? If you think so, listen <strong>to</strong><br />

this:<br />

"I have spent the best years of my life giving people the lighter<br />

pleasures, helping them have a good time, <strong>and</strong> all I get is abuse, the<br />

existence of a hunted man."<br />

That's Al Capone speaking. Yes, America's most no<strong>to</strong>rious Public<br />

Enemy- the most sinister gang leader who ever shot up Chicago.<br />

Capone didn't condemn himself. He actually regarded himself as a

public benefac<strong>to</strong>r - an unappreciated <strong>and</strong> misunders<strong>to</strong>od public<br />

benefac<strong>to</strong>r.<br />

And so did Dutch Schultz before he crumpled up under gangster<br />

bullets in Newark. Dutch Schultz, one of New York's most no<strong>to</strong>rious<br />

rats, said in a newspaper interview that he was a public benefac<strong>to</strong>r.<br />

And he believed it.<br />

I have had some interesting correspondence with Lewis Lawes, who<br />

was warden of New York's infamous Sing Sing prison for many years,<br />

on this subject, <strong>and</strong> he declared that "few of the criminals in Sing<br />

Sing regard themselves as bad men. They are just as human as you<br />

<strong>and</strong> I. So they rationalize, they explain. They can tell you why they<br />

had <strong>to</strong> crack a safe or be quick on the trigger finger. Most of them<br />

attempt by a form of reasoning, fallacious or logical, <strong>to</strong> justify their<br />

antisocial acts even <strong>to</strong> themselves, consequently s<strong>to</strong>utly maintaining<br />

that they should never have been imprisoned at all."<br />

If Al Capone, "Two Gun" Crowley, Dutch Schultz, <strong>and</strong> the desperate<br />

men <strong>and</strong> women behind prison walls don't blame themselves for<br />

anything - what about the people with whom you <strong>and</strong> I come in<br />

contact?<br />

John Wanamaker, founder of the s<strong>to</strong>res that bear his name, once<br />

confessed: "I learned thirty years ago that it is foolish <strong>to</strong> scold. I<br />

have enough trouble overcoming my own limitations without fretting<br />

over the fact that God has not seen fit <strong>to</strong> distribute evenly the gift of<br />

intelligence."<br />

Wanamaker learned this lesson early, but I personally had <strong>to</strong> blunder<br />

through this old world for a third of a century before it even began<br />

<strong>to</strong> dawn upon me that ninety-nine times out of a hundred, people<br />

don't criticize themselves for anything, no matter how wrong it may<br />

be.<br />

Criticism is futile because it puts a person on the defensive <strong>and</strong><br />

usually makes him strive <strong>to</strong> justify himself. Criticism is dangerous,<br />

because it wounds a person's precious pride, hurts his sense of<br />

importance, <strong>and</strong> arouses resentment.<br />

B. F. Skinner, the world-famous psychologist, proved through his<br />

experiments that an animal rewarded for good behavior will learn<br />

much more rapidly <strong>and</strong> retain what it learns far more effectively than<br />