After the finale of The Sopranos’ first season had been shot, but before any of the episodes had aired, Edie Falco asked the show’s creator, David Chase, what was going to happen next. Would they be coming back? Chase was pessimistic. “I told her, ‘We did our thing, but this is it,’” Chase says. He pauses for a few seconds, and his eyes get misty. He recalls telling her, “I don’t know how to explain it to you, but it has something to do with the fact that we had too much fun.”

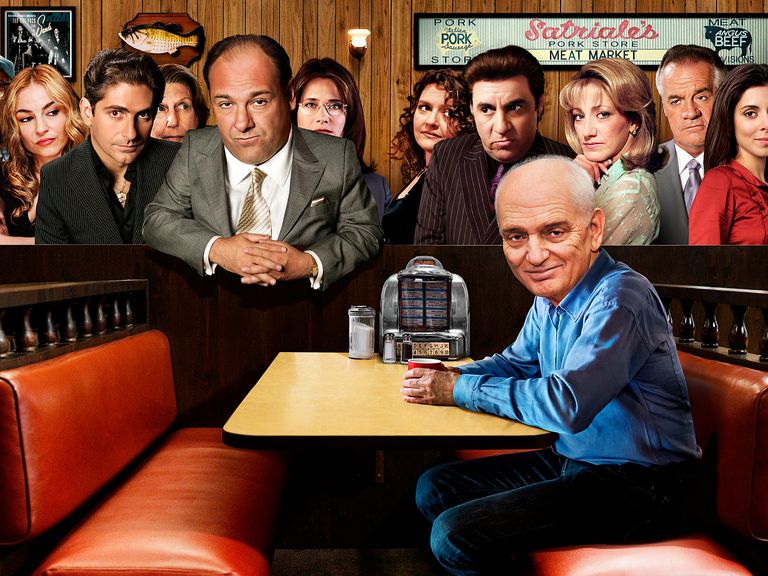

Chase never imagined that his show, about an anxiety-prone mob boss and his family, set in suburban New Jersey, would get picked up for a second season, let alone transform American television to such a degree that we’d still be talking about it 25 years after it premiered. The Sopranos, which ran for six seasons on HBO and went on to earn 21 Emmys, shredded the network television playbook. Storylines were left open-ended. (Whatever happened to the Russian?) Characters spoke in slang-filled, garbled half sentences and rarely expressed their true intentions. There were plenty of dream sequences, one of which involved a talking fish. The star of the show, the late James Gandolfini, was neither a household name nor an aspiring matinee idol. Yet his mobster with a troubled conscience captured the hearts of millions of viewers and ushered in a new golden age of television. Tony Soprano walked in his bathrobe so Walter White could run in his tighty-whities, Villanelle could sashay through a global killing spree, and Logan Roy could bark “Fuck off!” at anyone in his path.

And we’re still watching. Viewership of The Sopranos tripled in 2020 compared to prepandemic levels, and the trend doesn’t seem to be letting up. At the 2022 Super Bowl, Chevrolet seized the Sopranos moment with an ad featuring Jamie-Lynn Sigler and Robert Iler, who played the Soprano kids, set to the show’s iconic theme song and directed by Chase. Michael Imperioli and Steve Schirripa, who played Tony’s nephew Christopher Moltisanti and erstwhile brother-in-law Bobby Baccalieri, respectively, launched a popular podcast, Talking Sopranos that, as of December, can be streamed on Max, complete with clips from the show.

Before The Sopranos the domestic arena was considered a place where you could count on laugh tracks or corny conflicts that would be tied up in a bow by the time the credits rolled. Tony and Carmela Soprano, by contrast, fought bitterly—sometimes violently—and regarded each other alternately with contempt and compassion, often within the span of a single scene. Their children cursed, lied, sulked, and behaved like real, disrespectful teenagers. The drama within Tony’s suburban McMansion was treated with as much gravitas as the battles raging among members of his Mafia family. “Other modern shows weren’t really taking the gloves off in terms of how ugly it can get and how painful it can get” in families, says Terence Winter, a longtime writer on The Sopranos who went on to create Boardwalk Empire. For Falco, who played Carmela, the show felt like an experiment to see what audiences would make of an American family “with all of its ugly imperfections, only to discover that people are still lovable, maybe even more so, if you can see the ways they screw up, then wake up the next morning and try to do it all over again.” By the time the second season premiered (after Falco earned her first Emmy), HBO’s marketing team had a new advertising campaign: “Family. Redefined.”

At the time she was cast as the matriarch of the Soprano family, Falco wasn’t married and didn’t have kids. She worried that “nobody is going to buy this.” Now the mother of two teenagers, she was recently called in to meet with officials at her son’s school. They wanted to make sure she was comfortable with the English curriculum’s inclusion of The Sopranos. Would her son mind? “I said, ‘If you don’t tell him I’m in it, he might not even notice.’ ”

On a late fall day Chase, now 78, is at his house in Los Angeles. He’s self-deprecating and introspective, with a dry sense of humor and an unusual commitment to accuracy. When asked whether he has watched The Sopranos since it aired, he says that apart from looking at clips featuring actors he was considering hiring, “I never watched after Sunday night,” the prime-time slot when the show aired. (This was back when appointment viewing was a big thing.) Then he stops and thinks. “That’s not true. I’ve watched the last episode a couple of times.” Later I ask him if fans’ enduring passion for The Sopranos ever gets old. “It does not,” he says, and then he wonders if perhaps that means he’s needy. Again he pauses, then concludes that must not be true either. “If I was really so needy, I would have been too scared to break rules.”

It’s Chase’s thoughtfulness, his tendency to contemplate what he’s going to say, that some colleagues say could be intimidating. “David is one of those people where, if you ask him a question, he actually thinks about the answer instead of just blabbing,” Winter says. “He will sit there for five seconds, and you’ll be thinking, Is he mad at me?” He can also be blunt. Costume designer Juliet Polcsa recalls an incident when they were shooting The Sopranos on a hot summer day and one of the actors demanded shorts instead of long pants. Polcsa eventually relented, but when Chase saw the shorts-clad actor on the monitor, he told Polcsa, “Just put her in the fucking pants.” A few weeks later Polcsa and Chase were waiting for the elevator at Silvercup Studios in Queens, where the show was filmed. “There was this awkward moment,” Polcsa says, “but then he turned to me and said, ‘Just put her in the fucking pants,’ and we both started laughing.”

For Chase, who grew up in North Caldwell, New Jersey (where the Soprano family house was located) in an upwardly mobile Italian-American family, The Sopranos was deeply personal. The foibles of Tony’s narcissistic mother, Livia—for example, her refusal to drive if there was even a chance of rain—were based on Chase’s own mother, Norma. Tony’s therapist, Dr. Melfi, was named after his paternal grandmother, Teresa Melfi. Meadow Soprano’s friend Hunter Scangarelo was played by Chase’s daughter Michele. There are subtle family tributes throughout the series, such as the moment in the finale when Tony is sitting in a car listening to the 1963 song “Denise,” which is the name of Chase’s wife.

It was Denise who inspired Chase to enter therapy in the early 1970s to unpack some of his own issues. “Being married made it obvious that I was going to be living with another human being, and that human being didn’t necessarily get what the fuck I was doing,” he says. Although psychological self-exploration is a deep theme of The Sopranos (the pilot opens with the first of many scenes set in Dr. Melfi’s office), Chase says it wasn’t therapy itself but “the reasons I went to therapy” that became his creative muse.

By the time Chase was pitching The Sopranos, he was in his fifties and had been working for almost 30 years as a writer on such network shows as The Rockford Files and Northern Exposure. Although he was successful, writing for television had never been Chase’s dream. He found just about every show insufferably predictable, with rare exceptions like David Lynch’s Twin Peaks. Having majored English at NYU before studying film, first at the School of Visual Arts and then at Stanford, Chase always envisioned himself making movies. He was inspired by directors like Fellini, Kubrick, and Buñuel, artists who created films that made you think.

After signing a development deal in 1995 with the production company Brillstein-Grey, Chase recalls being startled when the company’s co-founder, the late producer Brad Grey, said he was confident Chase had a great television series in him. As flattered as he was, Chase says, “I didn’t want to have a great series in me. I wanted to make movies.” Still, while driving home from that meeting, he thought about an idea he’d had for a film about a mob boss with a difficult mother. His agent had told him that, when it came to Mafia movies, fuhgeddaboudit. But maybe, Chase wondered, this concept could work for television?

At the time HBO was evolving away from its original mission, providing subscribers with movies and televised live events, and embracing original episodic programming. Liberated from the advertiser-appeasing constraints of network television, with its prohibitions on nudity and profanity and its formulaic storylines, HBO’s content chiefs, Chris Albrecht and Carolyn Strauss, didn’t care if characters weren’t likable as long as they were interesting. “Chris and Carolyn deserve unbelievable credit for understanding that the art of storytelling was not always about the hero but the antihero,” says Richard Plepler, a longtime HBO executive who served as co-president from 2007 to 2012, then as chairman and CEO from 2012 until 2019. In greenlighting The Sopranos, Plepler says, “HBO made one of the greatest decisions in its history. We put the keys in the hands of a master storyteller who created a transcendent piece of art—not just television, art—that will stand the test of time.”

And indeed it has. Plepler counts himself among the fans who rewatched the entire series during the early days of Covid (for him it was the fourth time), streaming two or three episodes every night. “I would call David after I rewatched every season and say, ‘It remains magic.’ ”

Falco and her close friend Aida Turturro, who played Tony’s sister Janice, also attempted to watch the series during the pandemic, but they couldn’t get past the fourth episode. “It was too evocative,” Falco says. “It felt like therapy.”

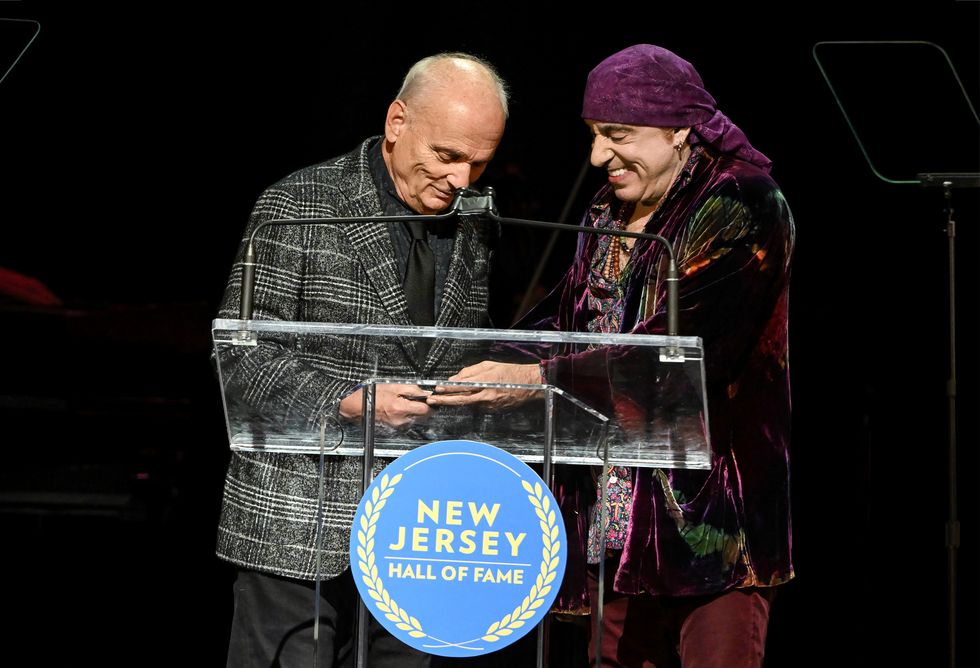

One evening last October, Chase, Falco, and several other members of The Sopranos cast were in Newark for Chase’s induction into the New Jersey Hall of Fame. Steven Van Zandt, who played Tony’s consigliere Silvio Dante, introduced Chase, praising him for taking television from the bottom of the entertainment industry’s hierarchy to the top, inspiring a creative renaissance. “Now that he’s accomplished this miracle, what does he want to do?” Van Zandt asked, waiting a moment to deliver his punch line. “He wants to make movies, the industry he singlehandedly made irrelevant.”

Chase has made two feature films since The Sopranos went off the air: Not Fade Away, a 2012 film that centered on a group of suburban teens in a 1960s rock band, and, more recently, The Many Saints of Newark, a Tony Soprano origin story released in 2021. Thus far the experience has been “not good,” Chase says. “I mean, I could say, ‘I got to make two movies.’ And everybody says you have to love the process, not the result—and I did love the process.” He’s currently working on a script for a third film, a collaboration with Winter, but despite rumors to the contrary, he’s leaving the world of The Sopranos behind. “It’s just enough already, you know?”

This story appears in the February 2024 issue of Town & Country. SUBSCRIBE NOW

Rachel Dodes is a freelance culture writer and co-author of the forthcoming novel, The Memo, to be published in June 2024.