They fear they have only a 24-hour window left.

Nagi Ali and Arwa al-Abili are a young couple kept apart by 9,000 miles, a pending final visa interview, her Yemeni citizenship, and they will probably beplunged into indefinite limbo on Thursday when the president’s updated travel ban comes into effect.

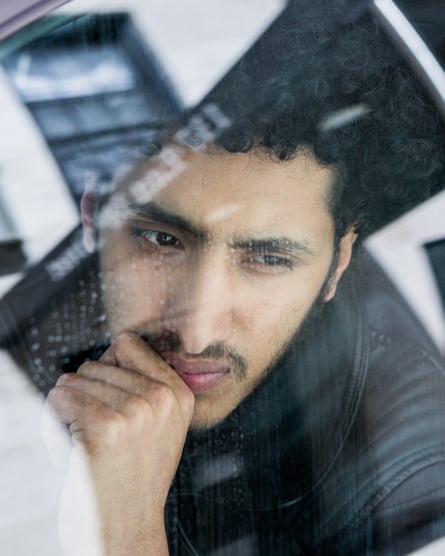

“It’s like you’re holding water,” says Ali, gazing out the window of a deli in East Harlem as the snow subsides, “and you’re hoping it won’t all slip through your fingers before it’s too late”.

Ali, a 22-year-old American citizen from Yemen, speaks on the phone to his fiancee for three hours every day, who is waiting in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. He checks the status of her visa online once every few hours too. The delay is agonizing and the hope for their wedding in New York is fading fast.

For her to get here, they will need either a last-minute court injunction against the new ban, or a swiftly scheduled interview at the US embassy in Kuala Lumpur, to unlock the final, procedural, stage of her visa application. If that does not work then their only hope would likely be a waiver determined later by a consular official. Their fear is that the president will effectively ban her from the country.

While advocates are not expecting the chaos inflicted by the first order due to new exemptions and a 10-day lead-in, thousands of people from the affected countries will still be caught up in the bureaucratic severity of the second ban. But fewer will be as tantalisingly close to reaching the US as Arwa Abili.

They had already done all the hard work. They completed a mountain of paperwork, presented documents and underwent security screening, all when the prospect of a Trump victory was something neither imagined could happen. The visa interview is merely “a rubber stamp” after their lengthy petition was approved in February, said their New York attorney Mohammad Saleem. “Frankly, they’ve done everything they need to do and we’re waiting for this last step. ”

It was August last year when Ali proposed to his 19-year-old sweetheart. He had travelled halfway around the world to Malaysia, to see her at a family wedding after years of estrangement.

They first met as teenagers in 2011, back in the Yemeni province of Ibb in the country’s south-west. Ali, visiting family, was lost in an unfamiliar city, and asked Abili for directions. He had never believed in love at first sight, but changed his mind after that day. “She was the only one on my mind since,” he says, cracking a smile. “She’s respectful. She’s patient. When she talks she has a lot of things in her head. She wants to be someone. She wants to help other people.”

By October, he had cobbled together the funds, working late nights and early mornings as an Uber driver, to pay for an immigration lawyer. He applied for a K-1 fiancee visa, which would allow her to enter the US for 90 days, for them to marry, and file an application for her residency. He placed a deposit on the venue for their ceremony, a hall in south Brooklyn, planned the menu for 100 guests and thought about their lives together and the children they would have.

But on 7 November, days after Ali sent the petition to the Department of Homeland Security, Donald Trump, who had pledged a “total and complete shutdown” of Muslims entering the United States, was elected president.

Ali received a frantic phone call from his fiancee. “Is he going to kick you out?” she asked. “Just come here to me. I don’t want a lot from you, I just want to be around you. We can live in Kuala Lumpur for the rest of our lives.” But Ali wasn’t ready to give up and still couldn’t believe Trump would follow through on his pledge. He was wrong.

Trump’s first travel ban, which triggered disorder at airports across America by barring those from seven Muslim-majority countries – even visas holders – from the US, was blocked by federal courts in January. The second, unveiled last Monday, contains exemptions for visa holders but again targets applicants from a group of Muslim-majority countries, including Yemen, and suspends the US refugee resettlement program.

“My heart was broken,” said Ali on hearing news of the second ban. “I woke up to the news and I couldn’t go to work.”

If her final approval does not come before 16 March, Saleem worries Abili might never make it to the US. The wording of Trump’s new order allows for the 90-day suspension of visa issuances to be extended indefinitely and the individual waivers contained within it are broadly defined and determined by a single consular official.

Even if the ban does indeed halt the interview proceedings and lasts for just the 90 days, Ali and Abili’s approved petition is only valid until 12 June. This is, two days before the ban will expire, meaning their entire application could be left redundant and they would have to start from scratch.

In an email sent to Saleem on 9 March, staff at the US embassy in Kuala Lumpur said they had not yet received Abili’s case file: “You may check back with us in two weeks,” it states. Saleem points out the embassy could schedule the interview without receiving the petition, but that appears increasingly unlikely.

“Now there’s no certainty,” says Saleem. “I can’t promise him anything and it has cast a big dark cloud over their future.”

Ali tries to stay optimistic. He talks about his dream of becoming an NYPD officer “it’s the greatest job you could do”, he says, and encourages Abili to think about applying to an American college to study dentistry. He can’t bear the thought of her returning to the civil war in Yemen.

“It’s too hard to believe you’re going to have to give up on your dream,” he says. “But we have to respect him [Trump] and his order. We will wait for justice.”

And what would he say to Trump, whose midtown tower he passes everyday during his Uber shifts?

“I would speak to him in a calm way for him to understand that the Muslim community is peaceful. If you ever had a chance to visit us you would see so many beautiful things.”

Additonial reporting by Mazin Sidahmed.