This interview ran in The Comics Journal #72 (May 1982)

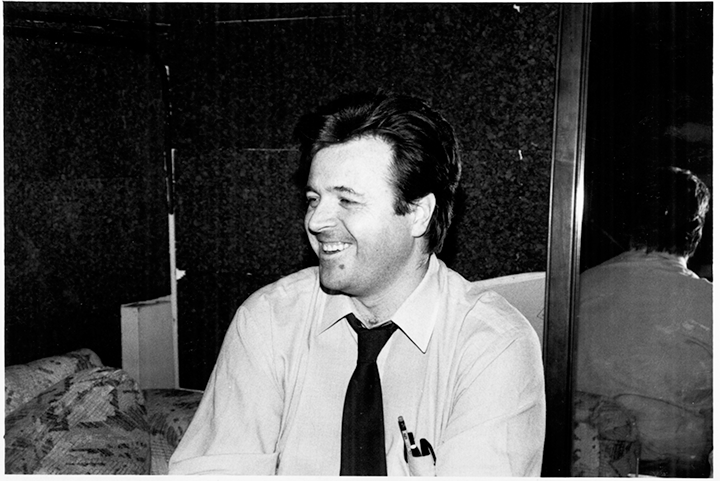

Neal Adams cannot be faulted for timidity. Adams’s influence on mainstream comics artists is still being felt, but aside from his public crusades — the Siegel and Shuster affair, the Comics Guild — little is known of his opinions, or even that he has opinions on practically everything, ranging from comic book artists like Don Perlin, Don Heck, and Dick Ayers) to world economy. (I predict his disquisition on why people don’t kill other people will become a classic.) At one point in the interview, Neal told me that taking people aback was standard practice for him. It must be. I was certainly taken aback a good many times in the course of the interview (his analysis of Hamlet springs immediately to mind), and looking over this interview, readers may be curious as to why I wasn’t more aggressive in nailing down Neal’s more outré ideas. The answer, in part, is that Adams is personally disarmingly reasonable-sounding, has a gracious and unflappable demeanor, and is not without considerable charm. But if the purpose of an interview is to reveal that part of an artist that his work does not or cannot reveal, this interview is a resounding success. Here is Neal Adams at his outspoken best, saying things I never thought I’d hear said, and seeing things in a way I never quite imagined possible. My thanks to Neal for our cover this issue and for his help and cooperation in assembling the visual material illustrating the interview. — Gary Groth

This interview was conducted on two separate occasions in Adams’s studio, Continuity Associates, in November 1981 and March 1982. It was transcribed by Gary Groth, copy-edited by Neal Adams, and edited by Dwight R. Decker.

GARY GROTH: Let’s start off by talking about what you’re doing in comics now, which is your series for Pacific Comics.

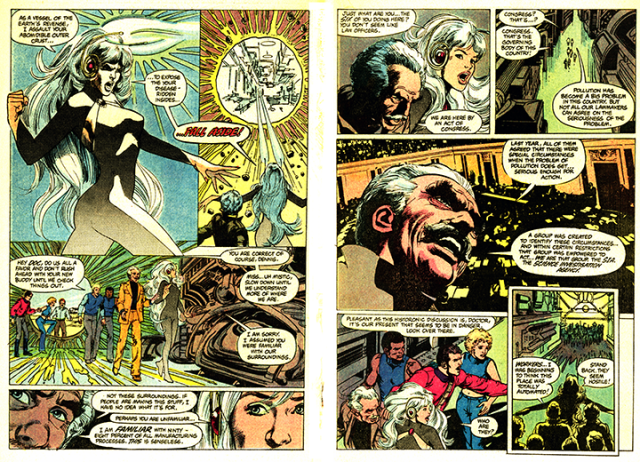

NEAL ADAMS: All right. I’m doing a feature called Ms. Mystic for Pacific that I was originally going to do with Michael Nasser. Mike thought it would be a good idea to do a female character, and I came up with all the concepts behind Ms. Mystic. We decided to do it together, but Mike has since deserted various forms of civilization in favor of living a very, very different life from what most of us live. So, until and unless he comes back and wants to join in, I’m doing Ms. Mystic for Pacific Comics on my own. It’ll be 12 bi-monthly issues. That’s about it. It’s a good character, an interesting character. It’s one of the five characters I created for a portfolio for Sal Quartuccio.

Had you drawn a Ms. Mystic strip prior to this?

No. Mike and I had worked on a strip for a while but it was put aside in favor of going our separate ways and doing other stuff. I finished it and it will be the first issue. Then I’ll be continuing to do stories for future issues.

Why did you go to Pacific instead of publishing it through Continuity?

I didn’t go to Pacific. Pacific came to me. The reason I agreed to do it with Pacific is that first of all, I don’t intend to be a comic book publisher. I intend to be a comic book — with the accent on book — publisher in that Continuity will do the graphic novels. Pacific Comics is interested in doing comic books, a field I still wish to be involved in. The reason I went with Pacific is because Pacific was willing to allow me to keep my character, not interfere with any other rights that I would have in the character, not give me a work-made-for-hire agreement and pay me a reasonable though not exorbitant amount of money for the right to publish it as a comic book. I felt it was a fair deal. In return, my job is to give them a comic book that will sell well and make money for them. It seemed incredibly fair compared to the deals that Marvel and DC offer.

Are you writing the strip as well as drawing it?

Yes.

Can you give me a little information as to what it’s about? Is it a superhero strip?

Ms Mystic is a superhero and her powers are the powers of the Earth and sky. She is or at least seems to be a witch. In her earlier incarnation, she was a witch and she was burned at the stake. And although she was burned at the stake, she survived by casting herself into another reality. However, she was trapped there. She could not leave that reality because she had used all her energy to get there and didn’t have the fare home. And not until today, when a group of people who work for a governmental agency that polices abuses in the ecology get together and do a “thing,” is she brought out of that reality. She sees that their fight for ecology is a valid fight. Now that she’s free from being burned at the stake for being a witch, she is able to make a contribution, which is based on her power and ability to draw elements from the Earth, the sky, the air, and the water to help her in her battle. She fights for Earth. She is a sort of very beautiful Mother Nature. That’s probably the best way to describe her.

An ecological superheroine.

An ecological superheroine. I think there are more problems on Earth than bank robbers, and if you want to deal with an Earth that bears some semblance to reality, you must recognize the problems of today. One of the problems is that we’re screwing up our planet. This is a character who, in an exaggerated form, fights for the Earth.

Will this ecology-consciousness run throughout the course of the strip?

Oh, yeah. That’s her purpose, that’s what she does. She doesn’t stop bank robbers, she stops people from polluting the air.

I understand you’re also involved, through Continuity, in publishing books by Wrightson, Michael Golden, Ed Davis, and yourself.. Could you talk about them?

We’re involved in a lot of books. The first is a Dracula-Werewolf-Frankenstein book I’ve done. It’s now complete and in the process of being colored. That book has been sold to Spain, where we will get our first color plates, and we’ll sell it to as many places in the world as we can. Another book that I had commissioned is a book called Freakshow. It was drawn by Berni Wrightson and written by Bruce Jones. Freakshow has been sold in Spain, and the color separations will be brought back to the United States and used in Heavy Metal. There’s also a book called Bucky O’Hare that’s written by Larry Hama, drawn by Michael Golden. Unfortunately, it’s not complete yet. It’s been held up because Michael had to move to Florida. There’ve been more delays than I would’ve hoped for in this book, but it’s so good that it’s worth waiting for. The book will appear eventually. Since its completion date is not yet known, it’s difficult to plan for it. However, the Belgian magazine Spirou has asked to run it. That may be the first publication.

Then there’s Cody Starbuck, which I commissioned Howie Chaykin to do. I’ve also purchased the rights to all the other Cody Starbuck stories, and they will start running in Spain and hopefully around the world. The first novel was printed in Heavy Metal and again will go to Spain with the other stories I purchased from Mike Friedrich. The whole idea is to consolidate all the Cody Starbuck rights so that we don’t find Cody Starbuck appearing drawn by someone else. It’s always been Howie Chaykin and it always will be Howie Chaykin drawing Cody Starbuck. If there’s ever the possibility of it growing into a greater property, it’s all consolidated and all under one head. Howard’s stuff is getting better all the time; he’s doing a wonderful job on Cody.

We also have Riders To Galaxy’s End, which is being drawn by Ed Davis. Ed’s not too well known in comics, but he’s a brilliant artist. He’s done some comic book stories, though not many. He’s slipped by most people. Ed has stopped working on the strip and may not have an opportunity to finish it because he’s doing something for Uncle Sam in South America. I don’t know exactly what it is, but he’s been forced to leave for about six months. He’s about half into that now, so he’ll either be back in three months or will not be back and we may never get to see it. Or it may have to be finished by somebody else. But like all the other projects, which are so ambitious that they’re really worth raking the time to create them correctly, it’ll be done eventually. Whether it will be finished by Ed or not, I don’t really know.

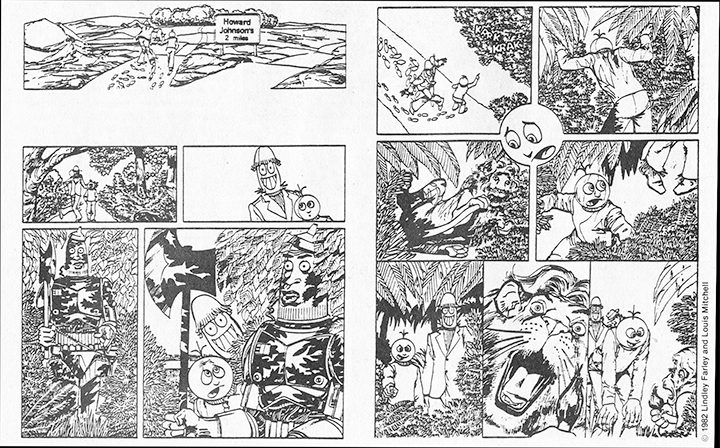

Finally, there’s a very strange strip called Tippy-Toe Jones, which was written by Lynley Farley, whom no one knows, and drawn by Lewis Michell, whom very few people know — he used to be Howie Chaykin’s assistant and he has a unique style. It’s very interesting, very different, and very strange. I’m rendering (inking) that story. It’s very hard to describe Tippy-Toe Jones. It’s a strange kind of book. It will stand on its own and people will either love it or hate it. It’s that kind of a thing. When I first read the story, I didn’t understand it. When I don’t understand something and it seems to be fairly well-done, I assume that that’s a mark of quality. So, I decided to go ahead with that project. I really don’t know what’s going to happen to it.

If you don’t understand it, how do you gauge if it’s well-done?

Well, you can cell whether or not it’s written well, and whether or not the person has a grasp of what he’s trying to do. Sometimes you can listen to a person’s conversation and realize they’re obviously in left field; they talk like they know what they’re talking about but they really don’t. I’ve also been around a lot of talented and creative people and there are many, many earmarks beyond what I just mentioned that show a person’s quality. Lynley, the writer, is a strange character. But in his own way, he’s very creative. And it’s hard to understand that kind of magic when it comes out of somebody, but when it’s there it really becomes obvious. It certainly becomes obvious to me. On the other hand, I have sometimes missed recognizing that magic, which makes me fallible, and this is no surprise to anyone. But I think of myself as a normal person, and if something tickles my funny bone, I figure it’s going to tickle somebody else’s funny bone.

You said all of these books are ambitious. Ambitious in what way?

Well, they’re ambitious in that they’re longer than most American comic book stories, so the artist has to have much more patience to do them. When you get into the habit of drawing 17 or 23-page stories, it becomes hard to draw 46-page stories. It also is a little more difficult to put more into each page, which is what the European standard demands. It’s tedious because each page has to be of a certain quality. It can’t go below that quality, and it has to be of that quality from the writing to the art to the color. Now, when I say, “to the color,” that leaves out an awful lot of American artists because most or them don’t concern themselves with color. When they do, they very often fail in their attempts to create a finished package. I think there are some American artists who have tried to do finished packages and have fallen short either because of an incompatibility of color art or the fact that it was done sloppily. An example of this is that thing that John Buscema recently did.

Weirdworld.

Which was colored and drawn very well, but somehow the combination of elements didn’t come together properly and people got tired of it very quickly. The thing is, when you’re dealing with that number of quality standards — writing, art, coloring, consistency — it becomes difficult to create a whole package. It’s tedious, it becomes more or a job, and it can very easily go wrong. So, it’s a harder thing. It’s harder because we’re not used to it.

You once said something to the effect that you at least think of color as an integral part of storytelling. And, of course, you like to have control over the coloring of your material.

Because we have not had control of color, we think it’s okay not to have control, but we still go to movies and watch TV where Mother Nature creates color and it’s augmented by camera, and lighting people. So, our audience is trained to accept color as being part of what they view, and they’re interested in seeing or hearing a story. I’m not so sure their imagination sees in color, but certainly their eyes see in color. So, for us to keep up with the times, color has to be part of what we do. It doesn’t have to be, but in my opinion, the less it does, the more we fail. It doesn’t make any sense to me to take the attitude that color is not important. It definitely is important, and if a person wants to take the opposite attitude, he makes a large mistake.

On the other hand, it’s difficult to control so many elements and still turn out a story. But after all, we are competing in the modern world and we have to create stories that compete with other forms. We have to compete with Raiders of the Lost Ark, Star Wars, and all the other good movies that are coming out with all the technical tools available to us. If we don’t think we’re competing with that stuff, then we’re making a very big mistake. I have a tendency to want to do the whole job, so it becomes much easier for me in particular to compete on that level. Someone may say that that’s a self-serving statement. Because I’m interested in it, therefore it’ s important to do. I think it’s just luck that I’m interested in it and that it is important to do.

So, you’re saying that because of audience expectation, color is superior to black-and-white?

Superior to black and white? I don’t think you can say a thing is superior or not superior. I think people expect to see color, and if you don’t give it to them, they won’t like it. See, it’s a tough world out there. If people expect to see something and they don’t see it, they don’t buy it. If they don’t buy it, you don’t make money. If you don’t make money, you can’t do it a second time. So, if you want to do it a second time, then you’d better do it right the first time. And I don’t mind living in a world like that. I think that’s fine.

You don’t view that as a compromise?

Not at all. I view that as competition, and competition is always a matter of compromise. But it’s a standard ingredient. It’s like making a take without using flour. It’s possible, I think, to make a take without flour, but it’s part of the ingredients, so why not do it?

In life you make choices for anything that you do. In other words, in the next five minutes or the next day, you have 500 different things that you might want to do. You make a choice and do one specific thing. When you do that one thing, you can’t do the other 499 things. You’ve compromised. Under those circumstances, it’s very hard to call it a compromise. You shoot for an average; you shoot for a percentage. I’m always shooting for a percentage. I’m always saying to myself, “Well, do I want to do this more than I want to do that?” And then I say, “Well, how much more?” And if it’s enough more, then it really is worthwhile to go ahead and do it. You don’t ever get 100 percent on anything because you’re always making sacrifices. So, you look for the best compromises. The idea is to make the fewest possible compromises and get the best possible percentage.

So, you do think these considerations of commercial competition should be the concern of the artist?

They have to be. If the artist presumes to be part of the world — which he doesn’t necessarily have to be (he can always go off and do it by himself) — he has to take the world into consideration. And once you take the world into consideration, you start making compromises. You don’t have to make compromises, but if you go off and decide to paint or draw by yourself, aren’t you making a compromise by giving up the rest of the world? That’s a pretty big compromise to me. So, from the point of view of creating something, if you are going to accept reality and society and the way things are, then you might as well go into it hip-deep and slug it out with everybody. You can’t decide to become part of The Machine and not accept certain aspects of the machine. You either accept it all and fight it out or reject it all and go off by yourself.

I think a lot of us tend to go off and be by ourselves for part of our time in order to lick our wounds when we get beaten badly around the ears. I think that’s part of dealing with society. After a while, it becomes too much and we go off, lick our wounds; and refuse to deal with it. After we get to feeling better, we come out and compete again. It’s a cycle, and everybody deserves and needs that time of going off and feeling sorry for ourselves so we can come back and fight again.

To get back to these albums you’re doing, will they be published first in Europe?

Yes.

And then will they be brought over here?

Yes.

Will they be published as albums?

Yes, they will be published as albums here.

Will Continuity publish them?

Possibly. I don’t like to say I’m going to do something if I don’t have solid plans to do it; that would be idle speculation. I think if Continuity can do the best job, then Continuity will do it. But my first responsibility is to the product property and the best deal it can possibly have. I’m not going to let Continuity deal with something that it can’t deal with properly.

You said the books are ambitious in terms of length; are they ambitious in terms of content?

Nah. They’re comic books. They’re good comic books, I would say. I really don’t expect them to be more than that. I don’t expect them to have any great message or preach anything, but I do expect them to be good comic books. If they’re not good comic books in my eyes, they have failed. And, as a matter of fact, if and when they’re completed — and several of them are — if they fail in the eyes of the reader, they deserve whatever disgrace is laid on them. In my opinion, the best work that the artist can do is in those comic books. There’s no excuse for any falling down on the job. A reasonable amount of money was paid for them, enough time was given, and they will be paid even more if they are good work. If they’re not good work, it’s a failing that I’ll be willing to take total responsibility for, and I’ll be willing to lay it onto the other people involved. “We screwed up.”

Is your criterion for a good comic book essentially superior craft across-the-board, or is it anything more than that?

No, it’s not more than that. Anything that a person adds beyond craft has to do with his personality. I’ll go to Berni Wrightson to get a book because he does have something above craft. But the thing I demand from Berni is craft, at least. Beyond that, whatever else he puts into it is up to him and his desire to add something to it. So, the Berni Wrightson story is not a story that doesn’t have a story. The story was written by a good writer, it’s clear, the words are not in unreadable type, the coloring is easy to understand, it’s not hindered by an artistic desire to create a new, super-involved type of graphic novel. It’s clear, simple storytelling, and anything Berni adds to it, he’s adding to it above and beyond that in his style, not destroying anything having to do with comic books.

Since comics have been almost chronically adolescent throughout their history –

Whew! Chronically adolescent! That’s an interesting phrase.

Do you disagree, or have any thoughts on that particular phrase?

It’s an interesting phrase. I’ll roll it around in my head a little bit. But go on, ask the question.

Have these albums broken any ground in terms of content or story quality?

Chronically adolescent. It sounds, at the first hearing, like it comes from a comic book reader who feels he’s finally grown up and maybe outgrown comics. That’s interesting.

Hmmm.

By that same view, James Bond movies are chronically adolescent, Hamlet is chronically adolescent. Why is Hamlet chronically adolescent? (So is Romeo and Juliet.) If you remove the flowery speech (which was the normal speech pattern in its day), then the story is very simple and easy to understand: it has to do with a family bullshitting each other, and it has to do with sword-fighting, cutting people, using poison, and stuff like that. So, all the elements are very plot-solid and easy to understand. There is very little subtlety and very little interreaction of a deep, psychological level. The emotions are very clear and easy to understand, usually: anger, jealousy, and rage, and not a whole lot more than that. [Address letters to Gary Groth.] Introspection to some extent. Full of thoughts that have been true since (and probably before) Aristotle.

I think that almost all good entertainment — and I separate entertainment in a lot of different ways — But good solid basic entertainment is adolescent. In other words, it appeals to the adolescent side of our nature. There are certain entertainments that don’t appeal to that side, and usually the adolescent in us finds them fairly boring. A person can be entertained by reading Freud, to a certain extent; a person can be entertained by ballet, by opera. (A person is usually entertained more easily by opera if he doesn’t know the story because almost all opera stories are really foolish.) I think because entertainment appeals to the adolescent side of our nature, the old man in us, which perhaps develops over a period of time, is not so much in need of adolescent entertainment. He’s more in need of quiet nights by the fireside or watching the sun set or reading a book in his own field that gives him information. But even he will go out and watch a James Bond movie and be entertained.

So, I would say, no, probably none of these stories are breaking new ground outside of appealing to the adolescent entertainment side of our nature. Tippy-Toe Jones, on the other hand, appeals to the devilish side of our nature, the nutty, the humorous side. I think it’s difficult talking about Tippy-Toe Jones because Tippy-Toe Jones is really a humor thing, but on a very strange level. So, perhaps one could say that, because it’s a humor thing and there are very few humor comic books, it could be breaking new ground. But I don’t really think so.

Your question excludes most forms of entertainment because of its basic assumption. Let’s deal with whether or not any of the comic books breaks any new ground: no. [Laughs.] But they’re pretty good at breaking up the old ground.

The last time I heard somebody breaking new ground was Byron Preiss.

Uh-oh.

[Laughs.] And it’s true that Byron broke some new ground. I find a certain amount of difficulty with people trying to break new ground before the end of the old ground is in sight, before the potential in comic books has been reached. I think there is so much potential in comic books that the idea of going off in some other direction at this point is really a waste of time. We don’t really know the extent of that potential.

Can that potential be reached unless we break new ground?

We’re having a problem with semantics here. I don’t think comic books have seen their greatest day, so if breaking new ground means turning it into another form, I think we have to wait until we finish with this form. That seems to me to be a long way off: The potential of comic books is the potential of the human imagination more than any other artform that I’ve ever seen in my life.

When you talk about the potential of the imagination being the end result, you’re talking about movies and comic books in the same breath. The only new ground that can be broken is experimentation within comics. If you’re talking about experimentation within comics, within the form, then anything that is new is different. I would say that, given that as a criterion, Ed Davis comes the closest to breaking new ground. I would say that, by comparison, mine and Berni’s are mundane, and Davis’s and the Tippy-Toe Jones thing are the closest to come to breaking new ground.

By breaking new ground, I was speaking entirely in terms of content, not form and packaging, if that clarifies things.

Yeah. I think we both came to the same conclusion at the same time, and based on that, Tippy-Toe Jones and Ed’s strip would be the closest. I really, honestly, don’t have the desire to break new ground. It has been said that I’ve broken new ground in comics. I would have to disagree with that because all I’ve done is drawn comic books a little bit better, but I’ve done comic books. I’ve stretched the medium a little, but I haven’t really broken new ground. I haven’t done anything that wasn’t already done. I just did an exaggerated form of it — nothing really new. If I do, I’ll let you know. I think that Corben may have broken new ground. [Pause.] It’s so hard to say, it’s such a nebulous concept, breaking new ground. What does that mean?

I think we need a new metaphor.

Let he who is without sin break the new ground … without sin? What does that mean?

Well, when I think of someone who’s done something extraordinary in the medium, I think of Kurtzman and his EC war books, which legitimized the dramatic form in comics. That’s more in terms of what I’m talking about.

Yeah. I think you could say Kurtzman has broken new ground. On the other hand, Will Eisner did it too, only Eisner did what Kurtzman copied. To a certain extent everybody’s breaking new ground. Everybody’s feeding everybody else ideas. It’s so hard to be so clear-cut and to make such big, sweeping statements like “you’ve broken new ground,” because every artist knows his own origins, every artist knows that he owes what he is doing to somebody else, or to 15 different other people, and there’s very little new that’s happening. It’s like cooking: you just put the ingredients together a little different. l think the guys who broke new ground are Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster. After what they did, it’s really hard to find people who’ve broken new ground because Jerry and Joe created a concept, visualized superheroes, visualized humans beyond what they are. That was an incredible concept. And I’m sure they didn’t create it. They just visualized it and made it possible for us to jerk around with it.

Do you still think that superheroes are a vital concept?

Sure. Superheroes are terrific. Superheroes are totally stupid postulations that could never exist in real life but are fun to play with. It’s like playing with toys. When we’re little kids, we play with toys, we think of things for them to do, and we use our imaginations. Some of us have gone on to have gigantic toys of incredible potential to play with.

Ridiculous things: there could not be a Superman. If there was a Superman, there wouldn’t be a World War II, right? There wouldn’t be a Viet Nam if there was a Superman. There wouldn’t be all kinds of stuff. He would end up King of the World and that would be it. He would seek power sooner or later, he would achieve it, and he would be the King of the World until he died — or until Luthor saved the world by destroying Superman, and then Luthor would be King. It’s ridiculous, but it’s fun to play with. It’s wonderful mental exercise.

To be philosophical about it for just a moment, the thing that men do that makes them greater than they are is their creation of new things. How does a man or woman — let’s not leave women out of this — get into the habit of putting aside all of the things he knows in order to delve into his imagination for things that he doesn’t know? And thus comes up with the concept that perhaps if you dropped something that weighed 50 pounds and you dropped something that weighed one pound, they would both reach the Earth at the same time? Since it’s obviously an illogical concept, what would make a person’s imagination come up with such a concept? What would make a person ‘think that the world could be round, and people not fall off of it? It takes a certain exercise of imagination, so exercise of imagination has in its own way made all the things that man has become, and with it he entertains himself as well.

Comic books are like training and exercising your imagination and they can lead to all kinds of good things. (Yes, they can lead to a lot of bad things too.) But it seems to me we have found a way to exercise our imagination in very, very safe ways. I would bet that there are an awful lot of inventions and concepts that are created by people who read comic books a lot when they were kids.

You’re saying as a result of their reading comic books?

As a result of reading comic books. As a result of somebody giving them a way of exercising their imagination. If you’re not thinking in terms of things that are impossible to do as being commonplace, then why should you accept the idea that a thing that seems impossible may actually be possible? After all, all new ideas spring from one mind, are disagreed with by everybody else, and are finally accepted by everybody with the statement, “How could we possibly have thought it was any different?” For an individual to think that way, he has to have exercise.

You’re not just going to suddenly come up with a totally new idea and then defend it with your life. You have to have other people creating and assuring you that it’s okay, other people mucking with concepts that seem crazy but are defendable on a certain level, in order for you to exercise your imagination. The exercise of the imagination is a difficult thing to describe because it doesn’t seem like a real thing. How do you exercise imagination? You exercise imagination by doing things that seem impossible. If you can’t do it yourself, you let somebody else do it. Read comic books so you’re willing to accept the irrational and the impossible as being possible. In Eastern philosophy, it’s part of the attitude that anything can be possible. In our system that sort of attitude doesn’t exist. We have to prove everything exists. So where do the new ideas come from? New ideas can only come from our imagination or some accident somewhere in a laboratory, but basically from our imagination, and for us exercising our imagination is not that easy. We need somebody to show us how.

Fortunately, we have somebody to show us how. We have comic books, movies, and science fiction. Those three things give every one of us an incredible freedom of imagination. Without them, I doubt if we would come up with a whole lot of new things.

Do you think it might be unhealthy to be constantly looking for novelty and new things!

Unhealthy?

Yes.

I think there are so few people in the world percentage-wise that really do look for new things that it’s hard for me to imagine that it could be unhealthy. Maybe if everybody switched over to trying to come up with new concepts, it might be unhealthy because there would be nobody there to run the farms and build the factories, but I don’t see that as a danger. In fact, I can’t think of anything about it that would be dangerous.

I’m talking about the fact that our consumer culture is constantly looking for new things, novelty, fashion, and trends to jump on.

What about it?

You just said very few people are looking for new things. But obviously we’re a nation of 240 million people who are constantly, endlessly searching for new things with which to occupy our time.

We are indeed, to a certain extent. I think what happens is that we’re being trained to look for and to need those new things. I don’t think it’s to the detriment of society, certainly. The desire to see new things is not as pervasive as it might seem. In some ways, it needs to be a great deal more pervasive than it is for it to even be a recognized concern.

You see, in my opinion, man’s function was to survive. And it wasn’t until modern times that man needed to be entertained as much as he does today, which makes survival so much more fun. It’s the entertainers of a society who make life seem better than it is. It’s the comic book artists, the movie-makers, the dancers, the singers, the writers, and the entertainers who make the hard work or what it is you do through the day seem better than It is because they do something for you. The entertainer has no function outside of that. He doesn’t plant food; he doesn’t make clothing. He really lives off society. He has no valid, useful function for survival. Instead, he pleases and satisfies the inner man that seeks to be entertained, that thing inside of you that seeks to expand your imagination. He appeals to that; that’s his function, that’s his job. That’s not a real function, that’s a created function. In a difficult situation, that person is useless. I don’t kid myself that I am a useful commodity in civilization. I’m not. I live off society.

The artist as parasite.

I’m definitely a parasite. If l were forced to survive, I would know how to survive along with everybody else, but I have been given the rare privilege of being a parasite off society and I enjoy that role very much. but I don’t kid myself that it’s not my role. It’s what I do.

We are given an incredible freedom nowadays to exercise that privilege to a greater extent than we ever have in the history of man. There are even many untalented people who are put into the position of being that kind of parasite because there is so much affluence, so much extra money, so much need to be entertained. We are no longer entertaining on a mass level. We can entertain 10,000 people and make a living from it. We have magazines that appeal to tiny segments of our society. We used to sell comic books on the news-stands and we’d sell them by the millions. Now we can sell comic books in “comic book stores” and actually make a living from it. There are people who go to that score and buy nothing but comic books, and that alone can support an industry. That is incredible. And it leads to wonderful freedoms. So, the artist in this day and age, has an amazing ability to do whatever he wants to do. The parasite has become King because he is able to express himself as much as he wants to. It’s a wonderland for a parasite. There’s no stopping him. He can do whatever he wants. He doesn’t have to paint pictures of the King, he doesn’t have to carve statues of Aman Ra, he doesn’t have to paint paintings of the leathercrafter’s guild. He can do anything he wants and somebody will give him money for it. What a concept!

What you’re saying is that we live in an age when everyone can be published and everyone can be appreciated.

That ‘s right.

Do you think that’s necessarily good?

Who knows? Society is hell-bent for its own end, whatever that end will be. I mean, I live a very good life and a very happy life because I don’t presuppose there’s a great destiny for mankind. I don’t believe that there is an ultimate, wonderful destiny that I must help to achieve, so l don’t run into the problem of wondering what the hell it is. I know what it’s all about. It has nothing to do with achieving anything. It has to do with the road to achievement. I’ve never met anyone who was as satisfied once he got where he was going as he was on the trip getting there. The job of mankind in life is to get to wherever it’s going, and the faster we get there, the more fun it is. The more speed we pick up on the trail, the more enjoyment we’ll get out of it. In the end, we might end up blowing ourselves off the planet and out of the universe …but we’ll get there anyway, sooner or later; we’re going to do it. Or we may have some wonderful destiny that I can’t imagine. I don’t know.

All I know is that it’s a good idea as long as we’re doing it to make it good because you can get a lot of satisfaction out of it. I’m curious about what the end will be of mankind, but I don’t know whether I’d really like to be there to experience it. Maybe I’d like to be there to experience it for about five minutes just to get the rush and then cease to exist. But after that, what have you got? So, my goal in life is to make a good race of it, to discover as much as l can, o do as much as I can, to find out as much as I can, to express myself as much as I can, and have a good time with other human beings communicating. But that’s the goal. The goal is the race.

You’re making a movie now, aren’t you?

Yes. The title is Nannaz. Nannaz is short for bananas. That’s my son’s name for this doll that’s been in the family for two years. Other people in the movie are Larry Hama, Ralph Reese, Denys Cowan, Gray Morrow, J. Scott Pike, Dave Manak, Moses Figerowa, Hank Ridley … I’m going to forget some people.

You wrote this movie?

I wrote it.

You directed it?

Directed it? I am directing it.

How long a film will it be?

Full-length, 90 minutes.

How do you go about distributing a movie like this?

That’s a good question. I have no idea. I assume a distributor will distribute it if he likes it. I have inquiries from two Grade B movie distributors at the moment. I think probably what I’ll do is take it around to the best people first and ask them to take a look at it and as they say no, I’ll go down lower and lower until somebody says yes. It’s not a concern of mine at the moment.

It all started this way: I had been working on some movies as a designer, and it occurred to me that I’d like to make some movies. I had seen how some movies are made and it struck me that not a tremendous amount of conceptual work is done by the people involved in movies. Many movie-makers wanted to be comic book artists but went off in other directions and decided to make movies.

They have never been trained as a comic book artist or as an artist: they have been trained as a movie producer or a director. I wondered how would it be for a person who was trained as a comic book artist to make a mid-career shift over into movie directing? I thought, that’s something I’d like to do, and from my observations it wouldn’t interfere all that much with creating comic books — because in many ways it doesn’t take anywhere nearly as much time, although it does take certain concentrated periods of time.

So, I thought, well, how would I go about making movies? Here I am, about to be 40 years old, which I have since become and passed this year, and what should l do if I want to make movies? If l want to be a director, it would take a long time. It would take years, and I don’t really have years. I’ve already done my time. Well, I thought, how about a production designer? I’II become a production designer. They seem to want my stuff. I can join the union and become a production designer. That doesn’t sound like me. Not the joining the union part; I’m in favor of organized labor, but just somehow my going out to Hollywood and doing production design for movies is not quite what had in mind. Beyond that, I’ve already done some of it and I sort of like it but it’s not very satisfying. Not only that: they tend not to do the stuff. You do a lot of work and they don’t make it. So, I thought, what about being a producer? Well, then I’ll learn to be an accountant and that’s all well and good, but I don’t know if I want to be an accountant. I thought, what the hell is left to do? It kind of leaves me out.

I thought, what about just making movies? What if I want to make movies? Then I should make a movie. In other words, to do the whole ball of wax and establish myself as a moviemaker. That sounds a lot better, that makes a lot of sense. How do you make a movie? Well, I guess you learn how to make movies. So, I took some classes at NYU and New School at night. I had one class on Mondays and one class on Thursdays, and they were pretty good classes. One was a lecture class and one was a practical class, a studio class. I absorbed the theoretical stuff, then I took the stuff to the practical class and I put it to use. I immediately went out filming, made a couple of shorts. They’re pretty good; they’re not great, but they’re pretty good. We did some nice effects; we got some good tension, some good drama. Some nice stuff. I showed two of them we did at the last Creation Con. Got a good reaction, everybody liked them a lot. Maybe they were being nice. Then, at the end of the class I decided I would make a full-length motion picture, which took my teachers aback. but that’s standard for me.

Taking people aback?

Yeah. “What? You can’t do that!” But I’d already gone far beyond the class. We had done color stuff and some adventurous techniques. So, I thought, “Well, I’ll make a movie,” but by then I learned that you can’t make a movie, that it’s impossible to make a movie. Impossible doesn’t sound too difficult to me. Impossible: I like that word. So, I thought, impossible, how can I deal with impossible? What do you need if you’re going to make a movie? You need a budget. Well, how much money am I going to need? If l think about that, I thought, I’ll never make a movie. I mean, first I’ll have to be like a producer and collect money from people and sell them this bill of goods. What if I don’t do that? What if I just decide to make a movie? Just go and make it. And I do it week by week, and as I run into financial difficulty I put it off and I just continue. And what if I plead and beg with people? Begging and pleading is not necessarily my nature, but I can do it when put to the test, so begging and pleading became part of what I did. So, I got people to work for free, I got people to give me equipment for free for a week here, a couple of weeks there. There are certain things you can’t get free, but you can actually do it if you know enough people and fancy yourself to be a good writer, and I fancy myself to be a pretty good writer.

So, I thought, what I will do is call upon the writer side of myself to provide me with a script that does not cost a lot of money. You see? I will write it and give this writer, who I am going to hire for nothing, information like there’s an apartment in Soho we can use for as long as we need it. There are the streets of Soho, there are people we know who would make good characters who would be willing to work for free. There’s this and chat. I gave this writer all the elements that were available that didn’t cost anything with the idea that he could concoct a story out of those elements rather than create a story that I would then have to pay for. He was very cooperative. He provided me with such a story. And we have started to film that story.

The big advantage to doing a story that way is that it ends up not looking like you were working with no budget. All of the things that were there were actual things, places that existed, people that existed, and it ends up looking like it cost a good deal of money. but it really cost very little money. When I say very little money, I’m at the point now of having spent $30,000. Now, a moviemaker recently went to a small house with a bunch of different people and made a movie in that house for $70,000. I guess I’m ahead of him because I have 10 minutes to go and it isn’t going to cost me another $40,000 to do it.

So, I’m doing what I’m told is impossible. The movie is actually happening. The goal of this movie is to show people that I know how to make movies. This is my first movie and there will be things wrong with it. But I think it will be entertaining and fun. I will try to sell it and I think I will sell it. And the people who were nice enough to help me will receive a portion of whatever it is I make on it and I will pay them back in some way, and I will begin making movies.

This sounds like the way John Cassavetes goes about making movies.

Perhaps. It seems to me that’s the only way people do get to make movies. They just decide to do it. It’s like becoming a comic book artist. You decide you’re going to do it and you go ahead and do it. I mean, you can’t let people stand in your way. If you have an ambition to do something, you’ll never get it done if you listen to other people. So, I just tend not to listen to too many people.

Can you give me a gist of what the movie’s about, the narrative thread?

There is a man who has two children, and he has been working on a piece of engineering gear for the last three years. The company that he works for has its home office in New York. He’s finished the project. He brings it to New York and stays over the weekend in an apartment of a friend of his. The following Monday, he will deliver this piece of equipment. That Sunday night, he tells his children (as they have been asking for a couple of years now) that he’ll allow them to babysit themselves for the first time. They are respectively 13 and 12 years old. He figures it’s fine. It’s a secure building. (The upstairs neighbor is an old friend and will look in on them from time to time.) No problems. They know where he’s going. And he goes out to dinner (his wife having died two years previous).

The kids are left alone with their doll Nannaz, who they have both agreed will be in charge, and a little valise that carries this piece of electronic gear. As it turns out, unknown to the father, that valise, the piece of electronic gear, has attained a value on the open market in the area of industrial espionage of approximately four million dollars. It’s unknown to him because he just-made the damn thing. It doesn’t mean anything to him, he just built it. He’s just being paid a salary, so he doesn’t understand the value of it. He has no conception of it.

But there are people who work for other corporations, and they will be paid a good deal of money if they can get their hands on it. Industrial espionage is a very mean business. If they steal it and they’re seen, they’ll be arrested and put in jail. If they steal it and they’re not seen, they’ll have four million dollars. There are three companies that are aware of this equipment. They know the family is staying in Soho, but they don’t know where. Each group has a different type of personality. One group is sort of street-punks, another is very dressed-up, very conservative, and the third group is a regular bunch of guys. They know that if they get this piece of equipment and they’re seen, whoever sees them will have to die. But each group is bound and determined to get that piece of equipment and to make that four million tax-free bucks, with which they’ll be set for the rest of their lives. The story is about them trying to acquire this case.

The two kids’ lives are endangered from the first, and their doll Nannaz will save them… we think. That’s his job. He’s been given this as an assignment by their dad: “You take care of that case, Nannaz.” And Nanna, does, without ever doing anything. Very mysterious little doll.

What film courses did you take?

The film course at New School is given by Arnold Eagle, who is a documentary film photographer. The film course at NYU is a lecture course given by Jim Manilla, who is a director and producer.

What were the courses about, specifically?

They were preliminary and basic courses in filmmaking. The first one by Manilla was a lecture, a three-hour lecture course once a week. The second by Arnold Eagle was a preliminary film course, which we disturbed by turning it into an advanced film course. Drove poor Arnold crazy. We went from black-and-white to color, then to sound almost immediately. He has three levels of courses. And a lot of the people in the class went along with us, because we formed a group and we rapidly went from beginner to advanced in the same course. We drove the poor guy crazy. He sat at the end of the course talking to us, saying, “This is the first class I’ve ever had that by the end of the course I discovered a group of my students was making a full-length motion picture, with sound. I’m going to have to revise a certain number of techniques.” “I don’t quite understand how this happened.” It was a lot of fun. Felt like a kid again.

I have the impression you were very interested in films before you took these courses.

Yes, true. I guess I’ve been interested in films for as long as everyone else has been interested in films, since everybody seems to be interested in films and filmmaking. It’s become part of our everyday conversation.

Did you grow up watching movies as a kid?

As opposed to what? Growing up in a convent?

Were they an integral part of your youth?

I read comic books and I went to movies as much as any other kid. My big thing, my interest in all of these things, is storytelling. I like to tell a story. I like to mold people’s emotions; I like to affect people. I get a charge out of it. It’s part of that entertainment aspect. I don’t like to go up on a stage and tap dance, but I do like to tell stories to people and get a reaction.

Did taking those film courses affect your approach to comics, alter your perception in comics in any way?

I don’t think so. I’ve had a very cinematic attitude towards my comics stuff anyway. That’s not my opinion, that’s everybody else’s opinion, so I suppose I have to agree with it. I don’t know quite what that means, but that’s what everyone else says …

How is it possible not to have a cinematic approach?

Yeah, you’ve got to wonder about it. “That’s very cinematic.” As opposed to what? I’ve done a lot of that — even in the commercial studios we have here, we’ve done a lot of storyboard work for commercials. And the truth of the matter is, it’s very frustrating not seeing the thing carried out, or seeing other people carry out your work. And I’ve gotten close enough to it that I really want to carry it out myself. It doesn’t seem to be getting in the way of doing my comic book stuff. but it does seem to be a rare opportunity to translate some of this stuff that I’ve had ideas about or even produced books about into movies. My Dracula-Frankenstein-Werewolf I would very much like to see as a movie. I think it would make a terrific movie. I would like to see even Superman vs. Muhammad Ali made into a movie. I think that would be a terrific movie. You see, they’re doing the Batman movie, and I’ll be goddammed if I think anybody in the world could do a better Batman movie than I could. I would love to write and direct the Batman movie. Somebody else is going to do it. Well, if somebody bought that right a year from now, I want them to know they should’ve contacted me. But next year they’ll be able to because I’ll be making movies. I don’t like to see that stuff slip away. If somebody does it wrong, I’d like to be there to do it right, either on that same character or on another character. I just have so many damn opinions that I’m not able to express, and I really don’t like sitting around telling people how I would do it. It galls me to do that. I’d just rather make the movie and show them.

When you talk of how to do a movie, you’re talking from a director’s point of view?

I think so. A writer’s point of view, too. There are a lot of areas of imagination that movie writers don’t understand. We’re getting a rash of movie writers who are actually able to write with imagination these days and it’s a surprise and a delight to see. But most of them don’t. When you turn a character like Batman over to a regular movie writer, how he could possibly, from his background, create a Batman movie is beyond my understanding.

Even someone like John Milius, who is probably one of the better writers, created a Conan that none of us recognize. I look at Arnold Schwarzenegger, I look at the photographs, and I don’t see Conan. I know what Conan looks like. Conan looks like what Frank Frazetta paints. Or Neal Adams draws. I mean, I know that guy, I know what he looks like. I’ve certainly got a general impression. Arnold looks like something else; he doesn’t look like that guy. For all I know, it may be a terrific Conan movie, but I have a feeling that it won’t be Conan. I think the only way you’ll be able to like it is by accepting that it’s not Conan, that it’s some other interpretation of a Conan-like character but not really Conan. And it galls me to see that happen, it really does.

So, I figure, rather than express that gall and get it out of my system, I’ll make movies and get it out of my system. I’m having a lot more fun doing that. I don’t like to bitch a whole lot. If you bitch a whole lot, that means you’re really not doing what you should be doing. I don’t think people have a right to bitch as much as they do. I think it’s a matter of put up or shut up. I don’t like people bum-rapping comic book artists who really try to do a good job, and it’s a shame to bum-rap people who aren’t doing a good job. I think it might be valid to bum-rap attitudes, but how can you say anything bad about Jack Kirby? You can say he’s not handled well. You can say he perhaps should be given a little less editorial freedom.

You’ve seen Captain Victory?

Yes, I’ve seen Captain Victory. But how can you bum-rap him? I mean, for Christ’s sake, it’s Jack Kirby. My attitude is, go out and do it better. You do it better. I’ll listen.

Gil Kane, for example, really has a right to say most of the things he has to say. He does perhaps say more than he might, but he’s earned the right to say a lot of that stuff, so you have to think, “He’s got the right to say it.” He’s earned the right to say it. He can show it on paper. So, it’s all right. There are other people I could say mouth off who really haven’t earned the right to do it. But that’s the way of the world.

Who are some of the directors who impress you the most?

I don’t really know directors too much. I’m not aware of names.

Or movies. I’m trying to find out what kind of moviemaking appeals to you.

My kind. I don’t spend a lot of time thinking of other people’s work. If a good movie comes along, then I like the movie. I’ll read the credits, then I’ll forget. When someone says, “What do you think of John Milius?” I’ll say, “Gee, I don’t know, what’s he done?” and they’ll remind me and I’ll say, “Oh, yeah, that was good, that’s fine.” I’m not an aficionado of any of this stuff. It’s just entertainment to me. When I stop entertaining, then I’m one of the entertained. I’m not a critic. My taste generally goes along with the general public’s taste. l like Star Wars, Raiders of the Lost Ark, Jaws, and movies like that.

But you must view things critically.

[Pause.] No, not really.

I keep making these silly assumptions.

Yeah. Things have to be really bad or really good for me to say anything about them. Most of my answers are nyah-nyah. Like, yeah, sure, what the hell. Y’know. Very few things are so bad that they’re just sludge, and very few things are so good that they make you glad you’re a human being. And if you ask me about one of those things, I’ll say, “Wow, that’s really great,” or I’ll say, “Yeah, that’s a piece of shit,” but all the stuff in between doesn’t concern me very much.

Could you have drawn the film you’re making as a comic book?

I would say I could’ve drawn an unsuccessful comic book of it.

Why do you say that?

Because it doesn’t deal with the realms of the imagination. That’s because of the budget problems. See, I understand the comic book audience; the comic book audience is not entertained by the same thing that entertains a TV audience. You don’t do a soap opera in a comic book because it’s so much better to watch it on television. The only areas we can really survive in as comic book artists are areas that are almost impossible to create in movies and in television. In some ways, people like George Lucas should’ve scared the hell out of us because he’s actually able to produce a lot of that stuff on the movie screen.

But for example, when you reduce Star Wars to a comic book, the truth of the matter is that the Star Wars book is not as interesting as The Avengers or The Fantastic Four. It still hasn’t gotten to that area of imagination. So it’s those areas where we can be successful, where we really extend our imagination out so far that it’s to the breaking point. Clearly it’s not to the breaking point [now] and won’t be to the breaking point for a long time.

But for me to make a movie, I have to make it on the level that’s within my ability. In some ways this is a very restrictive movie because it’s made for the budget that l have, which is nothing. If I were put to it, I think I could figure out a way to make Nannaz into a comic book that people would buy. But I would really have to be clever. It couldn’t be typical. It couldn’t just be drawn. I would have to add some stuff to it. I would have to add some fantasy in sideways to make something interesting out of something that was really not meant for a comic book. It’s like … [snaps fingers] what’s that movie about the husband and wife who have a kid … ?

Kramer vs Kramer?

Yeah. Nobody wants to read a Kramer vs. Kramer comic book, but Kramer vs. Kramer is a good movie. That’s the kind of thing that I mean. Not that Nannaz is anything like Kramer vs Kramer. Nannaz is more like Walt Disney and Alfred Hitchcock put together. [Laughter.]

That’s an interesting…

Well … if you think in terms of — what is it? — Journey to Witch Mountain?

You mean Bambi gets murdered in the shower or something like that?

[Laughs.] Sort of like that. In this movie, it operates on three levels of concern. The first level is the concern of the little girl, who feels that her brother is taking her on an adventure and that she’s having a good time. The concern of the brother is that somebody is possibly trying to steal this thing and that there’s a danger here from the thief, or maybe it’s a mugger. But his attitude is that the danger ends if he decides that, if the guy gets too close, all he has to do is turn around and give it to him. That’s the second level. The third level is the danger that the audience realizes: if the kids give up this thing, they’ll die. You see? Up to the point where the brother is concerned about the danger, that’s Walt Disney. Beyond that is Alfred Hitchcock. That’s what I mean. It’s truly a deadly situation, but the children can’t think of it that way. Not only can’t they think of it that way, but the little boy has to convince his sister that it’s just a game. And he needs Nannaz to help him do this because he’s a little bit worried about this situation.

I have the feeling that you’ve been using the word imagination as a synonym for fantasy when, in fact, this film you’re making probably requires an imagination but a different kind of imagination.

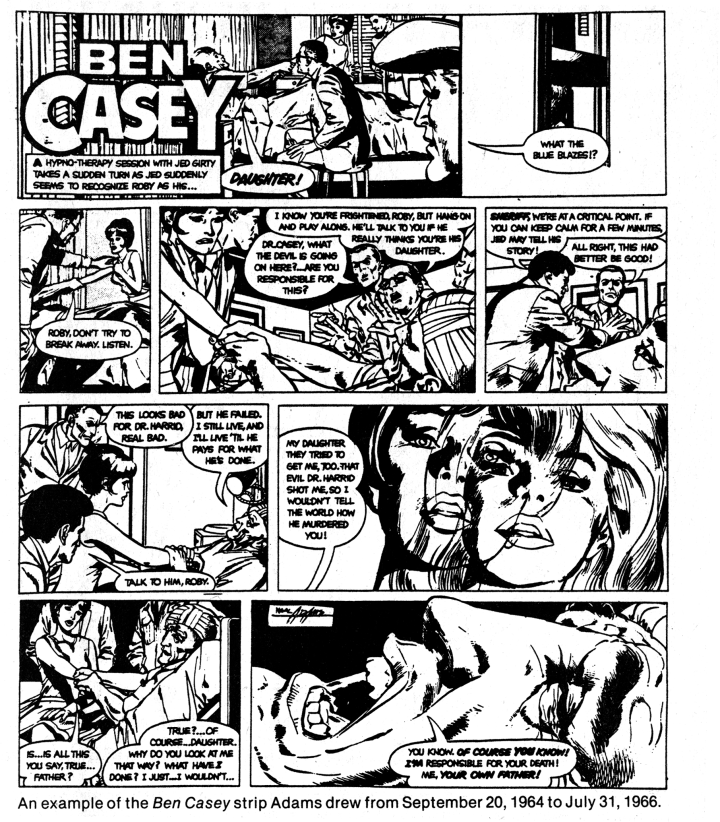

Nah. I haven’t been using it for fantasy, but it’s a good point. No. When I said that I could have done Nannaz so that it could sell as a comic book, I meant that I could do it by using a little bit more imagination than I did in writing the script, but I still wouldn’t turn it into a science fantasy or anything like that. There are ways of doing it, there are ways of expressing your imagination. Remember, my career started, as far as it being felt, doing a syndicated strip called Ben Casey, which competed with all the other strips and did very well. When I did it, it was a very popular strip and sold as well as any other realistic strip at the time and better than most. The reason for that was that I added things to It that went above and beyond the soap opera aspect of it, things that you don’t necessarily expect to find in a syndicated strip. You’d have to examine it carefully to note those things. One of the things I added was that I told a story every day, in three panels. And even though it was part of a continued story, there was a little story within those three panels. So, it was an exercise in imagination. That I consider an exercise in imagination. Comic books are an exercise in gross imagination: incredible, gross imagination. So, when I use the word with regard to comic books, I really mean imagination in every possible way. It just happens that comic books just tend to be very fanciful.

I really think Nannaz shows a great deal of imagination despite the lack of a budget. I still consider it a good movie, and I hope people will talk about Nannaz the way they talk about the first Green Lantern/Green Arrow story, as something that was wonderful for what it was. I hope they forgive it for its sins, but I also hope that it will be good enough that people will really like it.

You said you couldn’t make Kramer vs. Kramer as a comic book…

But you could! But you could. See, that’s sort of like … how can I put this gently … I don’t think Sal Buscema could necessarily make it into a comic book. I think Michael Golden might be able to.

Or Neal Adams?

Or Neal Adams. Neal Adams … l don’t like to use Neal Adams as a basis for comparison because, first of all, I’m Neal Adams. So, it’s just unfair to begin with. Everybody thinks they’re capable of doing anything. Most of us are not. I know for a fact that Michael Golden would be able to because he’s not Neal Adams and I can say more about him than I can say about Neal Adams.

You think very highly of Mike Golden.

I think he’s probably one of the three most intelligent young comic book artists around today. I exclude the old guys because they’ve been pared down to such a concentrated broth that we have the Jack Kirbys and the Will Eisners who will never be touched in their own realms. But in the new group we have the Frank Millers and the Michael Goldens. Then, we have the middle group (chronologically speaking), the Chaykins, and the Wrightsons and the Walt Simonsons.

I have a feeling we’re going to see some brilliant work by Walt Simonson soon. He seems to have turned out a lot of solid stuff and I think he’s on the verge of doing something fantastic.

What do you think are Simonson’s best qualities as an artist?

His best qualities as an artist? They used to be design, and a lot of people have come along to do Walt Simonson’s design. I think that when you distill out the design, it has to do with storytelling. Not storytelling necessarily as facial expression, but as body movements and placement of figures and movement, moving through a panel. I think that sometimes if you’re the only guy out there creating design, people tend to think that that’s the only thing you do. So, there was a lot of concentration on design. Then other people came along that did a lot of design work, and Walt’s stuff tended to look not-quite-so-spectacular because of the other people. Because there were more people. I don’t know if Walt recognizes it himself, or if it’s just my speculating and laying it on him, but I suspect that underneath it all the good storytelling is really the thing that counted for more and the design is secondary. Now with more people corning along, he might concentrate a little bit more on that. I think that the Alien book, for example, is a good example of storytelling and less design, considering what Walt has done in the past.

Can you explain what you mean by design?

Well, design is about a three-hour lecture. I don’t think we should get into it.

I just wanted a condensed version.

I wish I could condense design.

Would you say design is the most important element of comics?

No, not at all. l don’t think there is a most important element of comics, just the same as there isn’t a most important element of life. I once did an animated sequence for Donna Gillespie that was never aired because it was semi-pornographic and had allusions to lesbianism. Right near the end — it was a thing I’m quite proud of in it — there’s a very tight close-up of a girl’s face, perhaps from her lower lip to her hairline, a profile, in animation, done in line. Then, in color, a tear comes our of her eye and runs down her cheek. Donna Gillespie’s face comes in from the other side in animation, goes over to the girl’s face, and licks the tear off the girl’s cheek very slowly, onto her tongue, and pulls it into her mouth. It’s very sensual, but it’s done very subtly for animation. You don’t see that kind of subtlety in animation; that’s the reason I did it. And the most important thing in that whole thing was the tear. Now, you say, well, what about design, what about storytelling, what about these grand things? No. The tear, which doesn’t fit into a category. It’s a thing. It was the most important thing, and all of your concentration was on it. The way it was done was important, everything else was important, but the most important thing was the tear. So, someone might look at that as all of art and ask, what is the most important thing in art? You would say, the tear, and everybody would look at you a little funny. So, in each given circumstance it has to do with the values that are being presented and accepted. It becomes a very difficult question.

People who do not respect design, though, tend not to create good stories. There are a lot of people who have a natural design sense. For whatever I may have said about Sal Buscema, Sal Buscema has a natural composition and design sense. One of the things you can always count on in his stories is that every panel is always well-designed. It’s almost like the nature of the beast: he always designs it well. Whether he designs it great is a matter of debate, but whether he designs it well is not a matter of debate. He always designs it well.

John [Buscema] does the same thing. His is a little more erratic, Sal’s is a little more consistent.

Does design by itself mean anything if there’s no content underlying it?

Design by itself…

In other words, you were talking about Sal Buscema, and I’m thinking of the things he does for Marvel — The Hulk and things like that, which are essentially devoid of content.

[Pauses and whistles.] What I’m trying to say to you and failing is that I don’t have a right to comment on that. But the way you phrased the question implies that I clearly must have an answer, but I truly don’t. What I mean by that is, yes, of course, it is not possible just to have design and to tell a good story or whatever it is you’re trying to achieve. That is clear almost by definition if you accept that. Art is many things.

On the other hand, it is possible to express yourself in simple and pure design, as our museums will tell us. But you won’t tell a story about the Hulk. Whether or not the Hulk has content I think has more to do with whether or not you’re a seven-year-old or a 20-year-old. I think most seven-year-olds would say the Hulk has content, but they probably wouldn’t know what they meant when they said it.

I am not critical of the stories Sal Buscema tells because it is just slightly outside of the area in comics that I’m concerned about. What Sal Buscema does is what Marvel refers to as good, solid comics. And I think he does it very well. It’s the Sal Buscemas who are the mainstay of the industry. So, it’s difficult to talk about it from the point of view of creating your own definition and then judging it based on that definition. I would refuse to create my own definition. I think you are incorrect in saying that it does not have content. It has content for what it is supposed to have content for. It does not have content from the point of view of a Swamp Thing or a Green Lantern/Green Arrow or almost any Michael Golden book. But it does have substance that is valid for a kid and for some adults. But taking it one step further, Sal Buscema, for those of us who have actually paid a little bit of attention, has in some issues done more than he used to do. And there are some stories having to do, not with the Avengers, but another group… Do you know what the other group is?

The Defenders?

The Defenders. He has actually done some stories that have surprised me. I think a lot of us have put Sal Buscema aside and then don’t read him assuming he’s continuing to do the same thing, but there were a couple of Defenders stories that surprised me because they were actually quite different and highly charged with emotion. And that goes beyond what I said before about it being for a seven-year-old.

The wonderful thing about this industry is that it constantly surprises us. And if we become too critical of it, we tend not to look for the surprises. All of a sudden, Dick Ayers is off Sgt. Fury and goes over to DC Comics, where he starts producing very interesting comic books, some of them the better ones of the DC line. That’s because he’s not inking them himself and a certain amount of attention is given to him. All of a sudden we discover Dick Ayers is alive. Then there’s Don Perlin, who was over at Charlton producing relatively bad stuff. I spoke to him at an Academy meeting once. I looked at his work and I said, why is this guy working at Charlton and why isn’t he getting stuff? He’s not getting stuff because people ignore what seems to be mediocre stuff and don’t look for what’s underneath it. Now, I’m not saying Don Perlin produces the best comics in world but by God, he works at his craft and he tries to do a good job. And it took a certain amount of desk-pounding to get the people at Marvel to realize this, but once they got Don in there, they had a valid addition to their staff. And it was a surprise. It was like, Don Perlin? Don Perlin does those terrible things for Charlton. All of a sudden, Don Perlin is turning out good comic books: good story, good content, well-composed. What’s this all about! It’s a surprise. That kind of a surprise causes me to look with a jaundiced eye at people who are so anxious to criticize what’s going on or what seems to be going on, because all of a sudden somebody will do something …

Sam Glanzman. There are some things that Sam Glanzman did that are great, I mean just great! Most of his stuff I don’t like a whole lot, but by God, at some of those things I go, “Wow! Where did this guy come from? These little stories he’s telling are great!” I never like to take a negative attitude about it in general. Again, that’s one of the reasons I take the safe path. If something is terrible, really really rotten-terrible, it’s terrible. And if something is good, fantastically good, I’ll comment. But all the middle-ground stuff I leave alone because you never know when something will surface.

Are you saying that the story content can raise the standards of the artist drawing the story?

More than that. In every artist who’s doing what we call mediocre work, there’s the desire to do good work. A lot of times it just has to do with the situation, a lot of times it has to do with personalities. Look, everybody says bad stuff about Don Heck. I’ll say this about Don Heck. This has been a long time coming and I gotta say it. Don Heck produced some of the best early Marvel Comics ever: Ant-Man, Iron Man. Some of that Iron Man stuff was terrific. Whether he worked with Kirby or he didn’t work with Kirby, the stuff was really good comic books. l got off on it. Don Heck lost his wife. When she died, he fell apart. Only people who knew about it knew and understood what happened to Don and his work. I didn’t find out about it until three or four years ago. His work really went to hell. But the man lost his wife. He was just surviving. He was hanging on by his fingernails. And it took a lot out of him. Here’s an artist who has really been down, not a guy who never did anything, but a guy who did good stuff, and we know it was good stuff, and then he got shot down by life. And he’s tried to work his way back up, but it’s been really tough on him. Now, nobody’s letting him come up. Everybody’s ready to dump on Don Heck. The same potential he had when he was doing that stuff he has now. And I say this now: Don Heck is going to turn everybody’s face around. Remember, Don Heck did a job after I did my X-Men that everybody thought I did. Maybe Tom Palmer saved a lot of it, but Don Heck did a lot of that work. If people get off Don Heck’s ass and he’s given the right opportunity, Don Heck is going to show everybody that he is a major comic book artist.

In an interview you gave a couple of years ago, you said: My feeling about newspaper strips is that they should reflect the newspaper’s attitude. If a person is working on a syndicated strip, he should be working as a newspaper man. If he is doing a syndicated strip, he must become a newspaper man. He must take the newspaper’s attitude. His meat is information, the thing he presents is controversy, and the things a newspaper represents… Certainly a strip like On Stage has no real reason for existing, because it fulfills none of those functions. Wouldn’t that narrow and pragmatic an approach, if applied to earlier strips as it’s being applied more and more to today’s strips, have meant that strips like Krazy Kat and Segar’s Popeye and McCay’s work would not have been allowed space in newspapers?

Remember that when Herriman did Krazy Kat, the complexion of the world was very different. There wasn’t that much entertainment, so when you were doing a syndicated strip, the newspaper asked you to be entertaining. In other words, that’s how you could sell newspapers: by being entertaining. If it were true now — if all the televisions, radios, and movies were destroyed, or our economy got in such a slump that all we could do was buy the newspaper — then it would be the job of the newspaper to be entertaining. Since we have all those other things, it’s ridiculous for the syndicated strip to be entertaining because it’s outclassed everywhere it turns. There’s no way to be entertaining except to make a laugh. You can make a laugh, but even then there are comedians on television every night telling jokes. It’s just all over the place. So, if that is taken away — and it is taken away — if the ability to entertain is taken away by other media competing, then what is there left to do?

Krazy Kat would never be done now. It’s just not as entertaining as Saturday morning television for kids or the television shows or movies are for adults. That’s why it would never be done. We’re in a different time.

Do you consider that to be unfortunate?

No, not at all. Again, it’s a matter of percentage. You give up this so you can have that. But if you know that this has a greater value than that, you give that up and you try to give it up willingly without shedding a tear. I shed my tear and walk away. But I can’t say, “Gee, I’d like to have it back” or “Let’s try to save it.” It’s beyond saving, let’s close down the buggy-whip factory, it’s time to go. We have horseless carriages now, I’m not sorry that we don’t have blimps flying in the air. It would be nice to look up and see the Hindenburg, but it’s a waste of time.

Beyond that, there are much better things for a comic artist to do, like create a comic book or create an album. To put all of that energy in one place in full-color — how much better that is! Things don’t really go backwards. It’s just that people cling to the little things of the past, Not that they were better, but because in the past they were important. I’m not trying to laugh at them, I’m only saying that from an objective point of view — if such a thing exists — if I had my choice of doing a whole bunch of daily strips, I’d rather do the album. It’s so much more fun to do and see someone read the whole thing. I got a certain amount of joy doing my strip, but I didn’t get as much joy as I now get out of doing the stuff I do now.

Before Ben Casey, did you draw a Bat Masterson?

I worked as a background artist, as an assistant on the Bat Masterson strip for Howard Nostrand.

Was that a rewarding experience?

It was a rewarding experience because I worked in a studio that had an illustrator, two retouchers, and Howie Nostrand, and all of these guys had experiences to share with me from the commercial industry. They were really a great cross-section of the commercial art field and I learned so much about the potential of what was out there. That was more important than the work. Beyond that, Howie was trying to turn out a good strip. He introduced me to artographs and he taught me how to use the tools of the trade. So, it was an incredibly valuable experience.

You must have been in your teens.

I was 18.

And after Ben Casey you worked on a strip by Lou Fine?

No.

Peter Scratch?

I think that was during Ben Casey. It might have been after. I did a couple of weeks of dailies of

Peter Scratch for Fine, that’s all.

Did you actually work with Fine?

No, no. He had personal problems and I just did some fill-ins. That was at a very low point in Lou Fine’s career. He had many, many, many personal problems. His artwork had declined in many ways from the life that it had originally, to being a well-drawn, dull style, and it reflected the life that he lived.

You went from Ben Casey to comic books. Was Deadman the first comic book character you worked on?

No, I did some war stories for Bob Kanigher and some stories for Creepy for Archie Goodwin. The first character I did was the Spectre. Actually I did one short Elongated Man story. It was terrible, an atrocious story. Then I did some Spectre stories, then I did some Deadman stories. Burst upon the comic book scene! [in sensationalistic tone] It was strange because nobody at that time expected somebody to show up with so many new ideas or what seemed like new ideas. I took everybody by surprise. As far as I was concerned I was around for a long time. It was just that I wasn’t doing comic books and my entrance into the field caused a lot of uproar and mixed up even more a bowl that had already been mixed by Jack Kirby and other people, and just caused it to go crazier.

It was a lot of fun, but I couldn’t understand why everybody was taken aback by all of this stuff. l thought that’s what comic books were all about and that it would actually be a temporary excursion into comic books for me. I thought I would go into illustration and when I found that I enjoyed comic books more than illustration, I stayed in comic books.

You enjoy them more because of the continuity, the story?

The story. A lot of people have preconceived notions of what an artist is; they think of an artist as a thing that is born with talent and somehow becomes an artist through magic. The first incorrect thing about that is that I never met anybody who could say they were born with talent; they all developed it and worked on it. Some of them seem to have more facility than others.