Key concepts

Temperature

Heat

Perception

Sensory nervous system

Introduction

Have you ever tried to guess the temperature of the water in a swimming pool? On a hot day the water might feel chilly at first, but once you're immersed in the water you don't notice its temperature as much. On a cool day, though, the pool water that is the same temperature might feel quite comfortable from the very start. Is our body equipped to tell absolute temperature? Or is it all relative?

These questions might make you curious about how our bodies collect information about our environment, process it and form our perception of the world. Do this activity, and the next time you jump in the pool on a hot summer day you will be able to understand why you're about to feel so chilly!

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Background

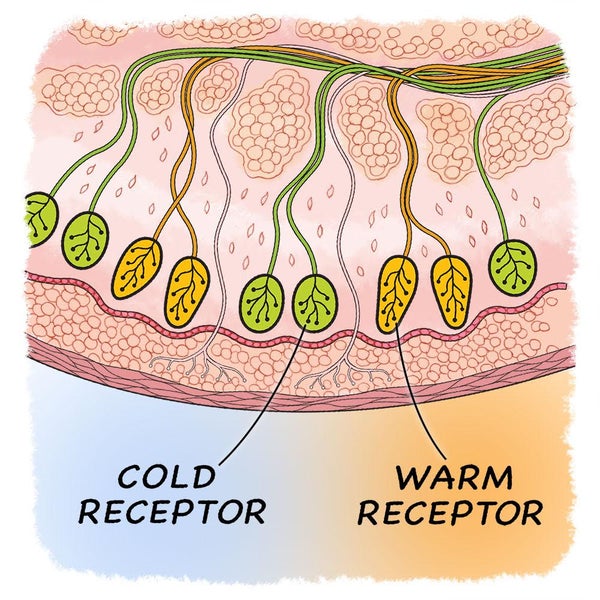

Our hands—especially our fingertips—are well equipped to collect sensory information from the environment surrounding them. They contain an immense number of sensory receptors. External circumstances, such as temperature, texture and touch prompt these receptors to produce electrical signals. The signals travel via a sensory nerve along the arm to the brain where they are processed, compared to past experiences and finally labeled.

Each receptor is triggered by a specific stimulus. Thermoreceptors detect temperature changes. We are equipped with some thermoreceptors that are activated by cold conditions and others that are activated by heat. Warm receptors will turn up their signal rate when they feel warmth—or heat transfer into the body. Cooling—or heat transfer out of the body—results in a decreased signal rate. Cold receptors, on the other hand, increase their firing rate during cooling and decrease it during warming.

Something interesting happens when your expose receptors to a specific sensation such as heat for a long time: they start to tire out and decrease their activity, thereby you will no longer notice the sensation as much.

Could this desensitization also alter our sensitivity to what we feel next? Try this activity and found out!

Materials

Three pots, all large enough in which to submerge both hands

Warm water (Do not make it too hot; test the water before you put your hands into the pot. If you still experience any discomfort from the warm—or cold—water, let your hands adjust to room temperature and start over using water at less extreme temperatures.)

Room-temperature water

Cold water (or ice cubes to add to room-temperature water)

Towel to protect your work surface

A clock to time yourself

Preparation

Prepare a work surface that can get a little wet by laying down a towel and removing any objects that should not get wet.

Fill one pot with very cold water. (You can also use room-temperature water and add a couple of ice cubes to cool the water in this pot.)

Fill a second pot with room-temperature water.

Fill a third pot with warm water. Be sure not to make the water too hot; you need to be able to comfortably have your hands in this water for a little while.

Procedure

Submerge your right hand in the pot with cold water. How would you classify the temperature of the water—cold or very cold?

Put your left hand in the pot with warm water. How does this water feel?

After having you hands in the pots for about a minute or two, pay attention to the temperature of the water in each pot again. Does the cold water still feel as cold as it initially did? What about the warm water? If it feels differently, do you think the actual temperature of the water in the pots changed considerably during this short time or has your perception of the temperature changed?

Now, simultaneously remove your hands from the pots with ice-cold and warm water and place both hands in the pot with room-temperature water. How would you label the temperature of the water in the pot? Does it feel hot, warm, lukewarm, cold or very cold? If it is hard to say, pay attention to what you would say if you felt only with your right hand and what would you say if you felt only with your left hand? Do your hands agree or disagree about the temperature of the water?

Extra: Instead of using two hands, give your index finger a warm bath and your middle finger of the same hand a cold bath. The sensory signals created by the thermoreceptor in this test run along the same sensory nerve up your arm to your brain. Would you still be able to say one finger feels cold and the other finger feels warm? Would you still get confusing messages when after a minute, you put both fingers in water at room temperature? Now try with a fingertip touching an ice cube and a warm cloth at the same time. Are you still able to say that half of the tip is warm and the other half is cold? Are you still confused when you put the fingertip on a room-temperature object?

Extra: In this activity the water in the hot and cold pots are different temperatures. What if you put your hand in contact with objects that feel cold or warm but are at the same temperature, such as a metal door knob or pot and the carpet or a wool sweater? These objects are all at room temperature but they appear to be different in temperature because they conduct heat differently. Let your whole hands touch these objects. Do you still get confusing messages if, after awhile, you put your hands in contact with a third material, such as glass?

[break]

Observations and results

Did the right hand feel as though the room-temperature water was hot, whereas the left hand experienced it as chilly?

When you initially placed your right hand in the cold water, cold thermoreceptors in your hand fired creating signals that, after being processed in the brain, enabled you to label the water as "cold." As the left hand was put in hot water, warm thermoreceptors initiated signals, allowing you to identify the water in this pot as "warm."

After awhile the thermoreceptors in your hands quieted down. They became desensitized and the water in the respective pots did not feel as cold or as warm anymore.

When you placed both hands in a pot of room-temperature water, however, your brain got confused. Your right hand entered with desensitized cold thermoreceptors and active warm thermoreceptors. The heat flow into the cold hand fired the warm thermoreceptors. Your brain interprets these as coming from a warm environment. You perceived the water with your right hand as warmer than it really was. A similar process happened in your left hand, which entered with desensitized warm thermoreceptors and experienced heat flow from the warm hand to the room-temperature water. Your left hand felt as though the water was colder than it really was.

As your hands perceived the water in the room-temperature pot differently, you got confused. Your brain returned conflicting information about the temperature of the water in the room-temperature pot. This experience shows that your perception of temperature is influenced by the previous environment.

More to explore Why Does the Floor Feel Cold When the Towel Feels Warm?, from Scientific American How Animals Stay Warm with Blubber, from Scientific American Somatosensation: Pressure, Temperature and Pain, from Boundless.com

This activity brought to you in partnership with Science Buddies