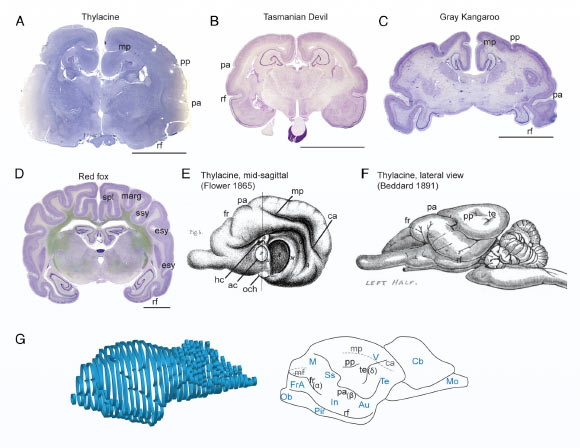

The thylacine (Thylacinus cynocephalus) is the largest of modern-day carnivorous marsupials and was hunted to extinction by European settlers in Australia. Its physical resemblance to eutherian canids, such as foxes and wolves, is a striking example of evolutionary convergence to similar ecological niches. However, whether the neuroanatomical organization of the thylacine brain resembles that of canids and how it compares with other mammals remained unknown due to the scarcity of available samples. Scientists from the University of Queensland gained access to a century-old hematoxylin-stained histological series of an adult thylacine brain kept at private collections in Germany, digitalized it at high resolution, and compared its forebrain cellular architecture with 34 living species of monotremes, marsupials, and eutherians.

Haines et al. found that the brain of the thylacine (Thylacinus cynocephalus) was typical of carnivorous/scavenger marsupials and did not resemble that of canids, despite external body similarities. Image credit: University of Melbourne.

The thylacine was the largest of modern-day carnivorous marsupials, commonly known as the Tasmanian tiger, or Tasmanian wolf, because of its distinctive stripes and canid resemblance, and the island they inhabited by the time of British settlement in Australia.

Thylacines were distributed throughout New Guinea and continental Australia over 3,000 years ago, but human intensification, competition with dingoes, and climate change likely led to their mainland disappearance.

In Tasmania, their numbers had already reduced substantially by the 19th century with the introduction of farming, a hunting bounty, and disease, with the last recorded thylacine dying in Hobart Zoo in 1936.

Despite anecdotal accounts in historical records, very little is currently known about thylacine biology.

Such knowledge could help better understand the causes of their demise, refine conservation strategies of endangered species including extant carnivorous marsupials, and provide clues about general evolutionary processes.

The endocranial volume of 18 thylacine skulls was estimated at 51 mL and, assuming a body mass of 28.5 kg, an encephalization quotient of 0.454 was calculated and discussed to be substantially smaller than eutherians of similar size.

However, this might be an underestimate due to body mass calculation artifacts; and more recent analyses of 93 museum specimens instead indicate a thylacine body mass of 16.7 kg, suggesting an encephalization quotient of 0.67.

However, rather than encephalization, overall brain size has been found to correlate with cognitive ability in primates, and in marsupials the best predictors of brain size include litter size, weaning age, and metabolic activity.

Given the remarkable heterogeneity in structure and function across brain regions, cytoarchitectural details within and between brain regions can offer additional insights into the drivers of brain evolution.

Macroanatomy of the thylacine brain compared to other representative species. Image credit: Haines et al., doi: 10.1073/pnas.2306516120.

“We analyzed high-resolution microscope slides of a brain taken from a thylacine after its death at the Berlin Zoo in Germany in the late 19th century,” said University of Queensland researcher Rodrigo Suarez.

“We compared the slides with the brains of 34 species of mammals including monotremes like echidnas and platypus, marsupials like kangaroos and quolls, and placentals like mice and humans.”

“The cellular organization of the thylacine forebrain is similar to that of other carnivorous marsupials.”

“We also saw that the thylacine’s cortical folding — which gives the brain its wrinkled appearance — is bigger than in their related marsupials but much smaller than in canids such as foxes and wolves.”

“The study showed that thylacine brains had enlarged olfactory and higher-order cognitive areas than other carnivorous marsupials, giving the species an increased sense of smell for its scavenging and hunting lifestyle.”

The findings demonstrate that brains and bodies can change in different ways throughout evolution.

“Brain adaptations made thylacines distinct from other carnivorous marsupials,” Dr. Suarez said.

“This research gives us a clearer picture of the nature of a long-gone species and provides benchmarks to both better understand other extinct and vulnerable marsupials and assess the future success of de-extinction efforts.”

The results were published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

_____

Elizabeth Haines et al. 2023. Clade-specific forebrain cytoarchitectures of the extinct Tasmanian tiger. PNAS 120 (32): e2306516120; doi: 10.1073/pnas.2306516120