Think about the last time you had hiccups. How did you cure them? Did you drink water very slowly, or hold your breath? Some swear by eating a spoonful of peanut butter.

Ideas for the best hiccup cures are as old as human civilization. Yet, scientists still find hiccups a bit of a mystery.

The Anatomy of a Hiccup

All mammals experience hiccuping, and we tend to agree that this involuntary reflex is annoying. It’s clear what a hiccup is: a reflexive spasm of the diaphragm, a curved sheet of muscle that’s crucial to breathing, located below the lungs and above the abdomen. Normally, inhaling and exhaling through the diaphragm is a smooth, uninterrupted motion. But sometimes, something irritates specific nerves connected to the lower diaphragm, triggering a cascade of actions that keep recurring in a loop.

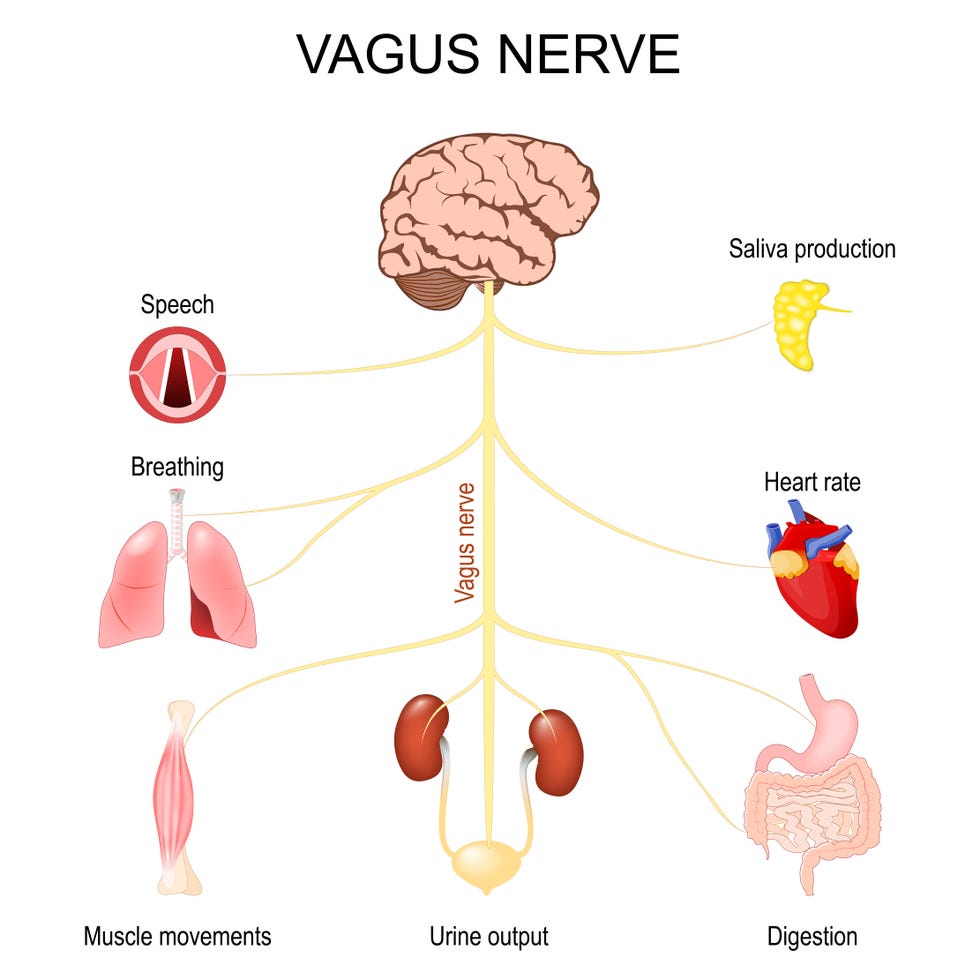

Here’s how the hiccup cycle starts: Say you eat something spicy. First, chemicals in that spice alert the phrenic nerve, an important nerve that winds its way around both your stomach and respiratory system. It also signals your diaphragm to expand and contract. Unfortunately for you, the brain center for the phrenic nerve happens to sit so close to the vagus nerve—which plays an important role in controlling your heart, throat muscles, and breathing— that the electrical activity jumps over. Now the vagus nerve sends its own signal, straight to the glottis—the middle part of your voice box—causing it to snap shut suddenly. Normally, your glottis gets the signal to close while you swallow, so that you don’t choke. But when this erroneous order comes down from the brain, you can’t help but make that characteristic “hic!”

The problem is, your phrenic nerve will keep screaming signals to your brain, repeating the cycle and making you hiccup repeatedly, until an irritation dissipates.

Generally, these triggers stem from spicy food, alcohol or carbonated beverages, but they can also come from acid reflux (heartburn). More serious conditions, such as some cancers or a stroke, can also cause hiccups.

Why Hiccup at All?

The human body is a machine that works partly on reflex. When something irritates your nasal passages, you sneeze. When something irritates your throat, you cough. Yet, hiccups are not so simple.

Dr. Daniel Howes, a professor of emergency medicine and critical care at Queens University in Ontario, Canada, proposed a likely hypothesis for hiccups in a 2012 paper published in Bioessays. He noted that when you hiccup, in addition to your diaphragm contracting and your voicebox snapping shut, your lower esophageal sphincter—which is normally closed to prevent food from your stomach backsliding into your esophagus—relaxes during the hiccup. “It must be to bring something up into your chest. And really the only thing that makes much sense is air. So in other words, it’s a burping reflex,” Howes says.

Why do we need this kind of burping reflex? Humans already burp.

It’s because all mammals nurse at birth, creating an evolutionary need to coordinate drinking and breathing at the same time. No matter how well honed this innate skill is, babies do end up inevitably swallowing some air. But expelling that air regularly could help an infant pack in as many calories as possible—about 30 percent more, Howes says. “Potentially, this makes a really big difference to their survival. This also explains why the reflex is actually far more common in babies than it is in adults,” he says.

Ali Seifi, a professor of neurosurgery and neurocritical care at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, thinks hiccuping is more common in babies and kids because the younger you are, the weaker your diaphragm is and the more susceptible that muscle is to spasms.

A New Treatment for Hiccups

Long-term or acute hiccups may be indicative of some medical condition and require drugs to treat them, but in general, hiccups don’t seem to have a surefire cure. Seifi wanted to change that.

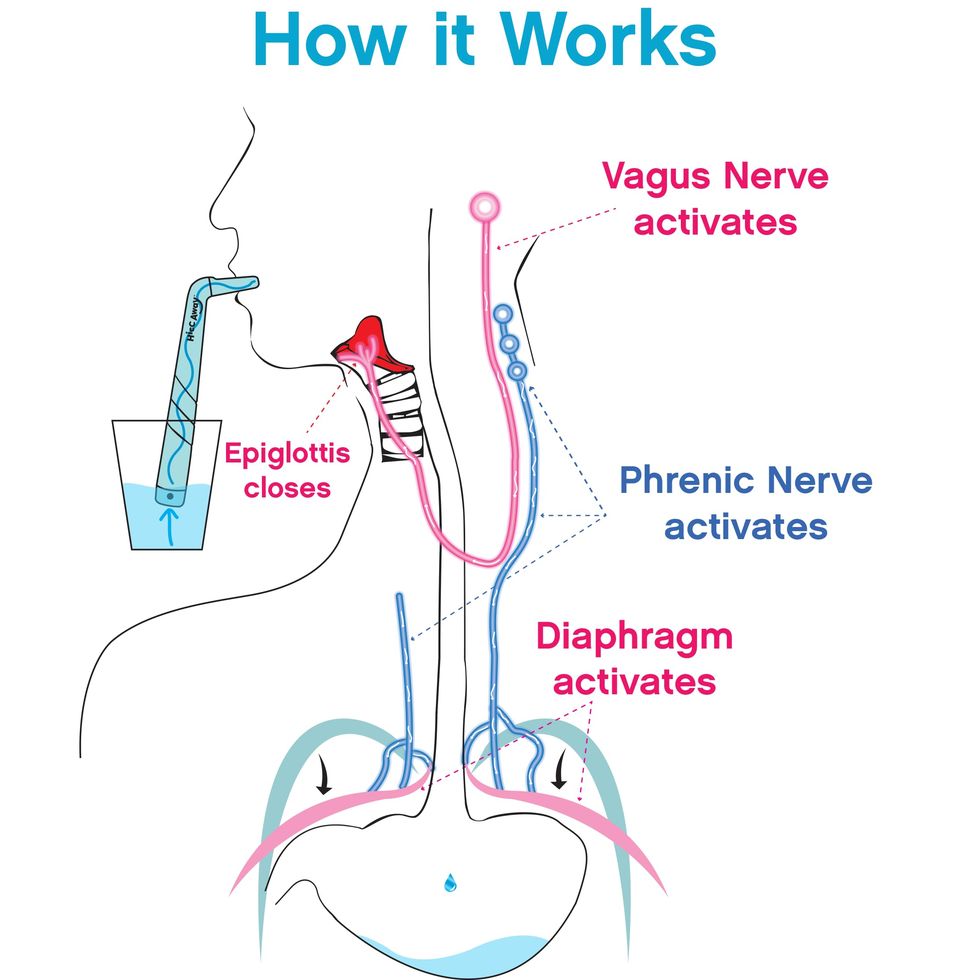

During his initial research, Seifi discovered that the diaphragm muscles exert a pressure equivalent to the pressure of water 100 centimeters deep (about half the length of a twin size bed) when they spasm during a hiccup. Over time, he developed the FISST, or the Forced Inspiratory Suction and Swallow Tool, with a research team. It’s a rigid tube with a pinprick hole at the bottom that lets in very little liquid. This tiny inlet valve means each sip of water through the tube requires forceful suction. When Seifi and his team had people with frequent hiccups take the tool home and test it, 90 percent of 249 people who responded to a survey reported that it worked, according to the study published in JAMA Network Open in June 2021. Users also found the tool more effective than home remedies, and they had no adverse reactions.

Later, Seifi parlayed the tube into the HiccAway, a product he presented on the TV show Shark Tank, and the hiccup straw is now a product on Amazon.

It works because water entering the straw from the tiny valve follows the laws of fluid dynamics. The amount of suction FISST users need to exert requires hard work, like drinking a very thick milkshake. In fact, FISST was designed to require the right amount of suction to override the 100-cm pressure of a spasming diaphragm.

Next time you hiccup, hopefully you’ll keep the hiccup cycle and the behavior of your vagus and phrenic nerves in mind to get rid of them—whether you use the HiccAway, or not.

Before joining Popular Mechanics, Manasee Wagh worked as a newspaper reporter, a science journalist, a tech writer, and a computer engineer. She’s always looking for ways to combine the three greatest joys in her life: science, travel, and food.