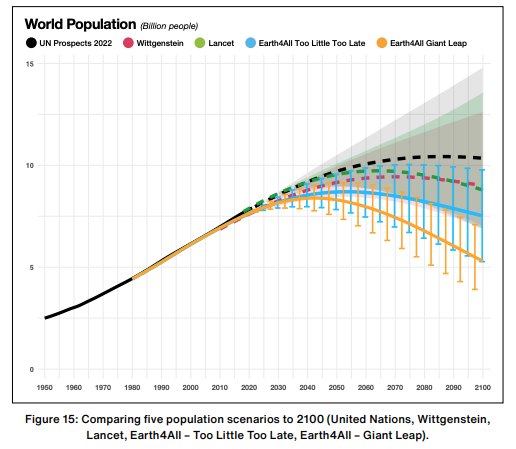

The United Nations projects the world’s population will grow by about 2 million people over the next 30 years to reach a high of around 9.7 billion people by 2050, and perhaps peaking at 10.4 billion by the mid-2080s—all before humanity’s growth begins to shrink in a stunning reversal. Eventually, Earth’s population could decline to between 6 and 7 billion people by the 22nd century, according to population researchers.

One reason for the projected shift is the declining average number of births per woman, especially among more developed regions with more educated women. In fact, the global fertility rate is around 2.3 children per woman, or half of what it used to be more than 60 years ago. Population growth rate (which takes births, deaths, and migration into account) is currently 0.9 percent—still increasing slowly—but by the year 2100, it is projected to be -0.1 percent.

Some potential positives can come with this: amid the human-led climate changes, rampant pollution, and mass species extinctions of today, perhaps Earth could recover some of its ecological and climate balance with a smaller, more manageable human population. We could benefit too, because presumably food and resources will be in greater supply for all.

But could population shrink also pose problems?

“We know rapid economic development in low-income countries has a huge impact on fertility rates. Fertility rates fall as girls get access to education and women are economically empowered and have access to better health care,” Per Espen Stoknes says in a press release. She’s the director of the Centre for Sustainability Energy at Norwegian Business School and project lead for Earth4All, a collaboration of economists and environmental scientists who model world economic and climate factors to understand how we can better support our global population.

Loud protests from some, like Elon Musk, interject that we need more people—not fewer. In 2018, the World Economic Forum tweeted: “Even as birth rates decline overpopulation remains a global challenge.” Musk tweeted in response that “Population collapse is an existential problem for humanity, not overpopulation!” He has also tweeted that “this is a serious problem. Ratio of retirees to workers is tracking towards unsustainability in many countries. An upside down demographic pyramid is unstable.” As the population ages and fewer babies are born to make up the difference, the proportion of people working will be less, and the young may have to shoulder a bigger chunk of health care and pensions for elderly folks.

Yet, a March 27 Earth4All non-peer-reviewed paper about “Sustainable Population Scenarios and Possible Living Standards” concludes that neither a high nor a low population size would break the planet. What’s disturbing the world’s natural climate and economic stability is the disproportionate material footprint of the world’s richest 10 percent, the paper’s authors say.

“Humanity’s main problem is luxury carbon and biosphere consumption, not population. The places where population is rising fastest have extremely small environmental footprints per person compared with the places that reached peak population many decades ago,” Jorgen Randers, one of leading modelers for Earth4Al, says in the press release.

The paper explores two scenarios for economic growth or collapse, depending on measures the world hypothetically implements to alleviate poverty by 2100. The first scenario, “Too Little Too Late,” assumes that the world continues to develop economically as it has since 1980, with similar rates of material consumption, carbon footprint, and income. In this case, some of the very poorest countries escape extreme poverty, and the world population falls to 7 billion. The long-term impact on general worldwide wellbeing, economic health, and the environment will be negative.

📈 Putting Human Population Growth Into Perspective:

• From the years 50,000 B.C. to 1 C.E., humanity grew slowly, from an estimated 2 million to just 300 million. After the Industrial Revolution, the next significant jump saw us break a billion by 1850, up from 795 million in 1750.

• By 1900, the human population had ballooned to 1.66 billion, thanks in part to more food and better medicine. The rate of growth over about the next 120 years only increased—and from 1950 to 2021, our numbers roughly tripled, from 2.5 billion to 7.91 billion.

• Today, Earth holds close to 8 billion people, with India and China in the lead. China has more than 1.4 billion people, with India trailing at just under 1.4 billion. With far fewer folks, the United States is third on the list, with a population of around 335 million. In the future, Nigeria’s population is expected to surge ahead, reaching 379.25 million by 2047.

So what will it take to ensure a more positive outlook for humanity? In the second proposed scenario, “Giant Leap,” nations invest heavily in education and health to alleviate poverty. They also model novel policy changes to ensure food and energy security, as well as gender equity and other social equalities. Researchers estimate that these actions would result in a slightly lower population peak and a count of 6 billion people by 2100. In this case, extreme poverty would be eliminated—totally—by 2060, and opportunities for future economic security will increase.

If everyone gets an equal distribution of resources, including food, shelter, and energy, everyone could escape extreme poverty, according to the report. “A good life for all is only possible if the extreme resource use of the wealthy elite is reduced,” Randers says in the release.

The interaction between human population and quality of life, with its dependence on natural resources and a healthy climate, is complicated. Certainly, more people has meant more demands on the planet. But maybe how we live is more important than how many of us are born in the future.

Before joining Popular Mechanics, Manasee Wagh worked as a newspaper reporter, a science journalist, a tech writer, and a computer engineer. She’s always looking for ways to combine the three greatest joys in her life: science, travel, and food.