When the dust had cleared from the devastation of World War I, the San Remo Conference of 1920 divided he remains of the broken Ottoman Empire. The conference recognized a British Mandate for Jordan-Palestine and Mesopotamia, a British Protectorate in Egypt, and a French Mandate for Syria. Consequently, European and American interest in archaeology in the Middle East was reinvigorated by eased access, for archaeologists could now bypass the formerly stringent control of the Ottoman government. What was once the purview of Osman Hamdi Bey in Istanbul passed to the British Director of the Department of Antiquities in Jerusalem. For the first time, it became possible for foreign buyers to purchase excavated objects or for them to be divided between interested institutions abroad, at the discretion of the Director of Antiquities. Fresh cultural debates about the meaning of archaeological evidence for knowledge of the Bible motivated excavations in these newly accessible areas, and accordingly artifacts from the Biblical-era late Bronze to early Iron Ages (roughly 1500–600 BCE) were prized above artifacts from all other historical periods. Parallel to these debates, popular interest in archaeology surged, witnessed by growing attention in the press. In the course of these developments, Clarence Fisher from the University of Pennsylvania requested permission to begin excavations at Tell el-Husn, a few kilometers south of the Galilee on the west bank of the Jordan River. Fisher had worked in Palestine before, with George Reisner in Samaria (1908–1911), and had made friends with the British authorities by offering his services as an architect during the British survey and restoration of the Dome of the Rock, begun in 1917. Tell el-Husn was once one of the private properties of the Sultan, and had never been excavated, although it had been identified in the massive 1882 Survey of Western Palestine as the ancient city of Beth Shean, or NysaScythopolis, well known from the Bible and classical sources.

When the dust had cleared from the devastation of World War I, the San Remo Conference of 1920 divided he remains of the broken Ottoman Empire. The conference recognized a British Mandate for Jordan-Palestine and Mesopotamia, a British Protectorate in Egypt, and a French Mandate for Syria. Consequently, European and American interest in archaeology in the Middle East was reinvigorated by eased access, for archaeologists could now bypass the formerly stringent control of the Ottoman government. What was once the purview of Osman Hamdi Bey in Istanbul passed to the British Director of the Department of Antiquities in Jerusalem. For the first time, it became possible for foreign buyers to purchase excavated objects or for them to be divided between interested institutions abroad, at the discretion of the Director of Antiquities. Fresh cultural debates about the meaning of archaeological evidence for knowledge of the Bible motivated excavations in these newly accessible areas, and accordingly artifacts from the Biblical-era late Bronze to early Iron Ages (roughly 1500–600 BCE) were prized above artifacts from all other historical periods. Parallel to these debates, popular interest in archaeology surged, witnessed by growing attention in the press. In the course of these developments, Clarence Fisher from the University of Pennsylvania requested permission to begin excavations at Tell el-Husn, a few kilometers south of the Galilee on the west bank of the Jordan River. Fisher had worked in Palestine before, with George Reisner in Samaria (1908–1911), and had made friends with the British authorities by offering his services as an architect during the British survey and restoration of the Dome of the Rock, begun in 1917. Tell el-Husn was once one of the private properties of the Sultan, and had never been excavated, although it had been identified in the massive 1882 Survey of Western Palestine as the ancient city of Beth Shean, or NysaScythopolis, well known from the Bible and classical sources.

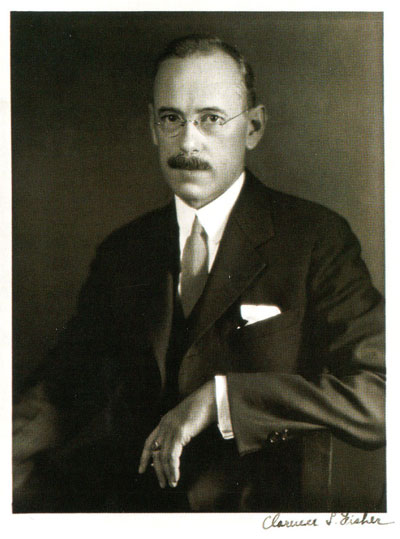

Clarence Fisher was “the ablest field archaeologist in America” according to his contemporary, William F. Albright, the founder of American Biblical archaeology. Hailed by one of the first manuals of archaeological method as the inventor of the Reisner-Fisher “American Method” of excavation, Fisher avoided the vertically oriented trench-excavation of contemporaries like Flinders Petrie—and his Penn colleagues at the earlier excavations at Nippur — in favor of horizontally oriented, open-area excavation that emphasized the relationship between architecture and artifacts. Albright’s praise came only after Fisher had been forcibly removed from his position as director of the Beth Shean Expedition by the Penn Museum in 1923, ostensibly because his “mental and physical health had deteriorated,” due to “an infirmity [that] began to express itself in malice,” as he explained in a letter to Alan Rowe. Fisher was dismissed from the Penn Museum in 1924. During those days of Prohibition in the United States, alcohol use may have been a factor. Nevertheless, Fisher was highly productive in the decade after his dismissal, taking a position at the American Schools of Oriental Research (ASOR) in Jerusalem and publishing results from excavations he co-directed at Megiddo and Gerasa. Fisher’s tendency to quit projects after a few years, followed by his composition of a formal statement of ASOR’s research program and methods in 1932, had the result of spreading his excavation methods. If his relationship with Penn Museum officials was stormy at times, Fisher was nevertheless a keen and creative administrator, an innovator in the practice of excavation, and an influential spokesperson and promoter of archaeology to the public.

Beth Shean was to be the first major excavation in the Near East after World War I. Fisher’s three seasons at Beth Shean (1921–1923) began the work of cutting into the medieval and classical strata of the tell’s high southern platform, where he uncovered evidence of an Ummayadqasr-type (palace or mansion) walled enclosure, an unusual Byzantine round church, and seven Byzantine houses. Due to Fisher’s early departure, these finds were published only later, and somewhat cursorily, by his successors Alan Rowe (1925–1929) and Gerald M. Fitzgerald (1930–1938). They continued Fisher’s work, cutting even deeper into the Iron and Bronze Age levels on the tell. By 1930, due to the Penn Museum’s dwindling enthusiasm for an expensive project that was not returning significant museumquality, Biblical-period objects, Rowe and Fitzgerald expanded investigations to include a necropolis and Byzantine monastery near the city’s northern edge, from which came many of the artifacts currently on display.

Penn Museum’s Beth Shean excavation was distinct from its pre-war predecessors in the area because it was directed by a museum rather than by a private foundation such as the Palestine Exploration Fund, or a colonial government like the British, which worked at the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, or the French, which worked at Byblos in Lebanon. With as much as $14,000 annually in funding (equivalent to $180,000 in 2013), Fisher’s excavation was able to set new standards for scale and rigor in documentation. All the same, the directors at the Penn Museum expected more than a return in knowledge for their investment. Letters record the intense negotiations that followed each season, as the Penn Museum directors and the British authorities determined which objects would return to Philadelphia and which were to go to Jerusalem or London. The Museum wanted Egyptian and Biblical period artifacts that were increasingly important as part of broader cultural debates concerning the Biblical past and, insofar as they created new “facts on the ground” through archaeological interpretation, the future of the Near East. Although liberal German scholars suggested that the Old Testament should be studied as literature, more conservative (and often Protestant)Anglo-American scholars led by W. F.Albright insisted that archaeology vindicated scripture as a historical document. Clearly, the Penn Museum team fell into the second group.

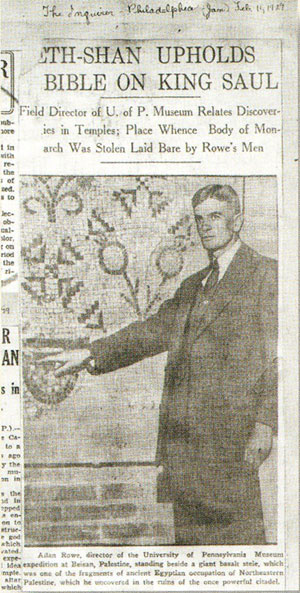

Fisher was skilled in crafting a message and attracting an audience, as is evident in regular coverage of his excavation in the New York Times. Even before excavations began, the Times reported that Fisher’s goal was the recovery of the iron chariots used to prevent the children of Israel from conquering Beth Shean from the Canaanites (May 20, 1921). Fisher later claimed in another Times article that his discovery of Egyptian commemorative stelae of Seti I and Ramesses II proved (counter to claims made by Albright), that Merneptah was pharaoh during the Biblical Exodus of the Israelites from Egypt (December 3, 1923).

Despite impressive discoveries from later periods, Beth Shean’s popular appeal came from its connection to the Biblical past: for the press, it was “one of the most important cities of the past, a spot over which no less than nine civilizations have lived and struggled,” the site of “the first reference to the Israelites,” place of “the last appearance of King Saul” (April 24, 1921), and a “repository of the ancient secrets of the Holy Land” (December 16, 1923). A single article in the Times gave attention to Late Antique discoveries—the Round Church in particular — but these were important only insofar as they connected to the Biblical narrative, essential for the creation of a Judeo-Christian map and appropriate pre – history for the fledgling state of Israel (September 3, 1922).

A nationalist narrative was also facilitated by the misidentification or neglect of Islamic artifacts in many of the Mandate and post-Mandate period excavations. The Times could even blame the demise of Beth Shean on the Turks, “who left a blight wherever their feet have trodden.” Islam was viewed as a foreign, destructive force, its arrival in the 7th century a marker of the end of life in the Byzantine city. The native Arab population was easily overlooked. This biased perspective has been discounted by recent archaeology, notably the excavations by the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. While clarifying many aspects of the Byzantine settlement, careful study of the lower city demonstrates the transition to Umayyad rule to have been peaceful, and the city prospered until the earthquake of 749. With the continuing vitality of the Late Antique city of Beth Shean clearly evident, the rich remains that were revealed, if unfortunately underplayed, by the Penn Museum excavations of 1921 to 1933 must now be reconsidered.

For Further Reading

Abu El-Haj, N. Facts on the Ground: Archaeological Practice and Territorial Self-fashioning in Israeli Society . Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001.

Davis, T. W. Shifting Sands: Rise and Fall of Biblical Archaeology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Holod, R., and R. Ousterhout eds. Osman Hamdi Bey & the Americans: Archaeology, Diplomacy, Art. Istanbul: PeraMüzesi, 2011.

Kersel, M. M. “The Trade in Palestinian Antiquities.” Jerusalem Quarterly 33 (2008): 21–38.

Walmsley, A. Early Islamic Syria: An Archaeological Appraisal. Duckworth Debates in Archaeology. London: Duckworth, 2007