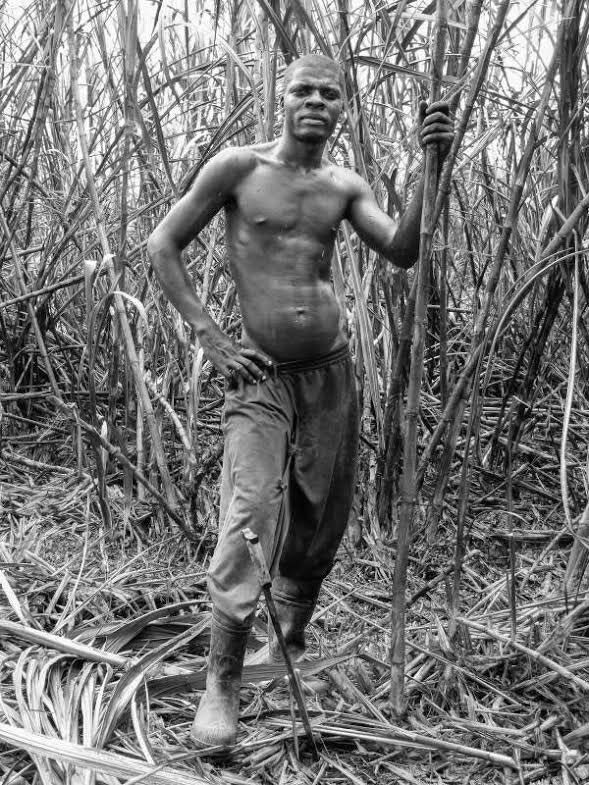

Cane cutters in the Dominican Republic. Photo by author. All rights reserved.

"We are like slaves in freedom, we work and we do not earn any money, we work for nothing ... we cannot even buy shoes, a shirt, a pair of pants ... we are like slaves in freedom because we are free to leave the job, we know that there are other places to go and work. We can leave, so we are free. But when one does this job he is like a slave, a prisoner, because without money he can't go wherever he wants. He has to stay and pay debts at the shop ... and then the job has to be finished."

With these words, Junior, a 22-year-old Haitian labourer, described to me his condition and that of many of his fellow migrants. They had left Haiti – the poorest country in the Americas – in search of better life opportunities, and now find themselves working under conditions of severe exploitation in the sugarcane fields of the Dominican Republic.

Cane clippers remain at the mercy of a reckless logic that decisively binds daily work with the ability to feed oneself.

They live in small, invisible migrant communities not far the heavenly beaches that attract thousands of tourists to the Dominican Republic every year. Known as bateyes, they are non-existent places on most of the country's geographic maps. Designed and built to accommodate sugarcane workers only during the harvest season (December to June), the bateyes have become real social communities inhabited by whole families of men, women and children. Some data suggest there are approximately 425 bateyes in the Dominican Republic, with a combined population of over 200,000 individuals. These, however, are rough estimates, as there is no official census and most residents are in the country irregularly.

In the bateyes, labourers and their families are housed in dozens in crumbling cabins without the most elementary services – running water, electricity, a toilet – and they spend up to 12 hours a day in the fields. Without protective equipment, and without health insurance and social security, cane clippers remain at the mercy of a reckless logic that decisively binds daily work with the ability to feed oneself, day after day.

Wages are paid per ton of cut cane, but workers do not have access to the weights and the amount received is quite arbitrary, often determined by clientelism and corrupt practices. Moreover, a minority of plantations still require workers to purchase primary goods from company-owned stores, where products are sold at increased prices. Wages paid in vouchers instead of cash to keep the system running, a system which creates vicious circles of debt that are very difficult to break.

The creation, and manning, of a sugar economy

Like all his fellow labourers, Junior comes from the first country to abolish slavery in the Americas; a slave revolt in 1804 gave birth to history's first black republic. Prior to independence, Haiti – then Saint-Domingue – had been the richest colony in the world, the source of three quarters of all the sugar consumed globally. The abolition of slavery and independence from the French motherland began a process of still-unchecked ruinous economic decline in Haiti, mainly due to the diplomatic isolation imposed by the international community on the new sovereign state.

The Dominican Republic saw an opportunity to fill the gap in the world sugar supply, and as industrial production came online it looked primary to its fledging neighbour state for cheap labour. A century later, starting in the 1950s when Haiti’s François Duvalier and the Dominican Republic’s Rafael Trujillo were in power, this necessity turned into a genuine official trade of workers between the two states. For almost 35 years, first Trujillo and then the Consejo Estatal of Azucar (CEA) recruited around 10,000-15,000 Haitian labourers each season directly from the government.

Cane cutters in the Dominican Republic. Photo by author. All rights reserved.

Haitian migratory flows in the Dominican Republic continued to be promoted, stimulated and institutionally facilitated by both states until at least the mid-1990s, when a crisis in the international sugar market put a brake on the demand for agricultural labour. In 1999, following the approval of a public enterprise reform law, most Dominican sugar plantations were sold to private investors through 30-year lease contracts. As several studies have highlighted, as well as the numerous testimonies I collected directly from workers who experienced this transition to private management, the privatisation process has led to a serious deterioration of life and work conditions on the plantations as well as a rise in new forms of exploitation.

The high availability of unskilled labour and the low level of demand combine to create a highly recyclable labour market. The large concerns running the plantations exacerbate labourers’ already disadvantageous position by using pre-existing factors like irregular migratory status alongside certain management policies to further bind labourers and their families to the plantations. Prohibitions on gardening and the raising of livestock on company property are two such policies, as is preventing cutters from monitoring how their output is weighed. To ward off protests and strikes, private management organises work shifts into brigades of constantly changing labourers so that no two workers spend too much time together. It is no coincidence that there are no free trade unions, especially when – as many workers reported to me – all signs of dissent are silenced with the threat of dismissal.

Pursuing new lives, despite the obstacles

As a result of declining employment opportunities and the progressive deterioration of working conditions on the plantations, many labourers have begun to look for jobs outside the rural and agricultural context of the bateyes. One path has been to return to the main urban and seaside resorts of the country to engage in various activities in the informal economy. For some this has proven a good way forward, and especially second and third generation Haitians in the Dominican Republic have sometimes found ways to fit fully into Dominican civilian life.

Until recently that transition was helped along by the acquisition of citizenship by ius soli (birth right citizenship). Not all appreciated this shift, though, and the government instrumentalised the increasing urban presence of Haitians to aggravate racial prejudice against the entire Haitian population. This turned into a controversial constitutional reform that retroactively eliminated the right of ius soli all the way back to 1929, effectively revoking the nationality of more than 200,000 people, many of whom have already been deported.

Paradoxically, this has indirectly transformed the bateyes – which have always been seen as isolated socio-economic ghettos, almost geo-political enclaves – into relatively safe places for Haitian migrants. They serve as shelters for those threatened by the spectre of forced repatriation. Yet, even more than before, the Haitian migrant population of bateyes remains an extremely exploitable labour reserve, willing to accept any condition imposed on it. Even more than before, to use the words of Junior, the labourers are "like slaves in freedom."

This Guest Week presents the results of research carried out by the team of ERC GRANT, ‘Shadows of Slavery in West Africa and Beyond (SWAB): a Historical Anthropology’ (Grant Agreement: 313737). The team has researched in Tunisia, Chad, Ghana, Madagascar, Morocco, Pakistan and Italy under the leadership of Alice Bellagamba. The team has invited Joanny Belair, Raúl Zecca Castel, Irene Peano, and Layla Zaglul Ruiz to participate in the discussion.

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.