The Etherealization of the Eternal Feminine in Late 19th Century Art

The concept of the female as something immutable and pure, has often grown into apotheosis. Art from the late 19th century exemplified this in the form of the Ewig-Weibliche.

Benjamin Blake Evemy / MutualArt

Feb 12, 2020

The concept of the female as something immutable and pure, has often grown into apotheosis. Art from the late 19th century exemplified this in the form of the Ewig-Weibliche.

William-Adolphe Bouguereau, A Young Girl Defending Herself against Eros, 1880, oil on canvas, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Since the dawn of man’s artistic endeavors, the female form has been much celebrated, revered, and worshipped. From the Paleolithic Venus and the Sorcerer painted on the walls of the Chauvet Cave in southern France, to Man Ray’s 1924 photographic masterpiece Le Violon d’Ingres, the image of women has been deified and etherealized. Yet one particular period in art history archetypically exemplifies the eternal feminine: the late 19th century.

The term ‘eternal feminine’ (Ewig-Weibliche in German) was first popularized by Goethe, who mentioned the term in the second part of his tragic play Faust. This philosophical view of the female, depicting the sex as pure, delicate, celestial and immutable, was subsequently resurrected by Nietzsche in the latter half of the 19th century. This is one of the reasons why the philosophical principle became so prevalent among artworks produced during that period.

The concept of the female as something immutable and pure, has often grown into apotheosis. The female form not only being of immense aesthetical value and emotionally (or erotically) pleasing, but a subject of sacred transcendence. This exalted portrayal of the feminine was often viewed as something that lifted mankind to holier ground - something that set one on an honest, upright, and moral path.

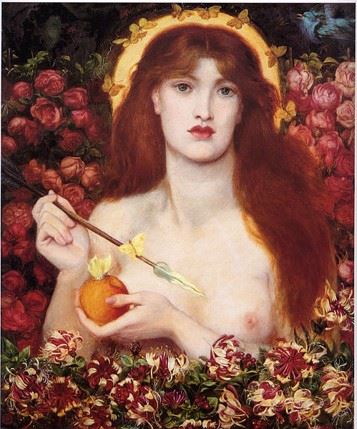

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Venus Verticordia, 1864-8, oil on canvas, Russell-Coates Art Gallery and Museum

This is exemplified in Rossetti’s Venus Verticordia. The title, derived from Latin, meaning ‘Venus, Changer of the Heart’, referring to the Goddess’s ability to set hearts toward virtue. Venus’s gilded halo, the soft shimmer in her eyes, the abundance of butterflies – an age-old symbol of resurrection. But as is typical with the eternal feminine, there is strong duality in this symbolism, as clearly laid out in the poem Rossetti penned to accompany his masterpiece:

“A little space her glance is still and coy;

But if she give the fruit that works her spell,

Those eyes shall flame as for her Phrygian boy.

Then shall her bird's strained throat the woe foretell,

And her far seas moan as a single shell,

And through her dark grove strike the light of Troy.”

The erotism is suddenly very clear: the infamous apple, Cupid’s arrow, the abundance of red roses and ripe honeysuckle; the distressed blue bird aflight in dense shadow.

John Atkinson Grimshaw, Midsummer night or “Iris”, 1876, oil on canvas, private collection

Perhaps the artistic tendency during this period - not just to portray, but to etherealize the eternal feminine, stemmed from society’s blossoming interest in the occult. Séances, Tarot card readings and esoteric orders had become almost common fare in Victorian-era England. John Atkinson Grimshaw’s Iris, being one pertinent example, in what at first glance could be misconstrued as nothing more than a beautifully crafted fantasy, is in fact something much more profound. Iris, messenger of Gods, twists in somnambulant flight amidst a woodland, dense and darkened. Again, the subject is depicted with a halo. But what is truly interesting, and makes for a good point of reflection, is that Iris herself has been interpreted as a form of ectoplasm. Whether Grimshaw held any significant personal interest in spiritualism or the occult, or if he was simply catering to the vogue of the period, is a subject of speculation, although in certain variants of the painting, the artist himself identified the figure as the spirit of the night.

In a period of primarily public prudence regarding sexuality, this ubiquitous etherealization and deification of the eternal feminine could have in part stemmed from erotic repression. The Victorian period was rife with metaphorical expression of sensuality and sexuality – whether subconscious or conscious: Dracula, subtly erotic art, death obsession, and floriography exemplify this. In art, the language of flowers and their feminine symbology at times blatantly surpassed pure metaphor.

Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, The Roses of Heliogabalus, 1888, oil on canvas, private collection

The Roses of Heliogabalus is an example of this surpassing of metaphor, and a painting in which the concept of the eternal feminine is copious. The ethereal tibicen playing amidst suffused light, the floral-chapleted women, the cascading rose petals covering the lovers in a writhing sea of ecstasy; it is a scene both erotic and celestial, in which lust and life are celebrated in all their opulent glory.

One extremely strong theme in the etherealization of the eternal feminine, is that of innocence becoming apotheosis. The eternal feminine is demure and virtuous, the height of man’s conjugal desires. She is so much so, that she takes on the role of the Madonna. A holy and sacred mother, both vestal and lifegiving. She has existed since the dawn of man, and who will be there at the end of his reign. She is Devaki, she is Venus, she is La maja denuda, she is Westerhouse’s Boreas, and Nabokov’s Lolita. She is eternal.

For more on auctions, exhibitions, and current trends, visit our Magazine Page