Mannequins: A Tool of the Artist's Workshop

«Long since forgotten, mannequins—also known as laymen or lay figures—were among the most essential but little-acclaimed tools of the artist's workshop from the Renaissance to the early 20th century. The mannequin pictured at left, a superb and rare surviving example, is a recent addition to The Met's study collection of historic artists' materials. This highly complex object was made in France, the center of mannequin production, and was sculpted of hardwood in the first half of the 19th century.»

Left: The Met's recently acquired 19th-century French mannequin. All object images courtesy of the author

Intended as a means of improving and refining the drawing or painting of figures, not as a substitute for working from the human model, mannequins were crafted to simulate muscle, flesh, and bone. Ours is a type known as mannequin perfectionée, a term denoting its elaborate internal structure and naturalistic finish. Its abstracted androgynous geometric form is imbued with a lifelike appearance evoked by its large scale (five feet, three inches), its skin-toned gesso surface, sharply honed face, torso, limbs, and wasp waist, and, not least, the fine bones of its feet and the creviced palms of its hands. Its blank stare, heavily lidded eyes, and enigmatic expression place it in an eerie space between human and nonhuman.

Unlike conventional sculpture that is carved and painted, or mannequins made for medical or fashion purposes, this avatar is fully articulated. The flexibility of its shoulders and arms, hips and legs, wrists and ankles allows it to be configured into any position possible of the human body; even each finger is easily manipulated to individually open and close. This remarkable agility was made possible by an intricate system of rotating wood ball-and-socket joints, numerous dowels, and an elaborate internal mechanism: a wood-and-metal armature, or "skeleton," that holds its parts in place. The artist could further stabilize the mannequin to defy gravity and allow it to hold its pose by dampening its mechanical joints to swell the wood. To gain a better understanding of how this figure was so successfully engineered, conservators plan to x-ray it in the near future.

Mannequins of this quality took about a year to craft and were extremely costly, but were in great demand from the late 18th to the mid-19th century. Always specially commissioned, each is believed to be the work of several artisans, but little is known about who made these highly individualized models. Many were passed down from master to student, or changed hands by sale, gift, or inheritance, and by the 19th century they could be rented from colormen—merchants of artists' supplies—or purchased second hand. Our example, long ago given the moniker Ottakar, came to us from a New York portrait artist who acquired it from his teacher, to whom it had been given many years earlier, dating our current history of the figure to about 1900.

Many treatises attest to the important role these proxy humans played for artists for their own work and as teaching tools; the earliest mention is by Filarette in his Treatise on Architecture (1461–64), with descriptions continuing beyond Denis Diderot's Encyclopédie (1763) and throughout the 19th century. Such books and manuals explain how to pose these realistically proportioned models for use in drawing, painting, and sculpture, and many offer instructions for constructing them in wax, cork, wood, or as figures stuffed with horsehair and hemp with papier maché heads.

Purportedly first used in Western art by Fra Bartolomeo, the workshops of such notable artists as Leonardo da Vinci, Correggio, and Luca de Cambiaso also employed mannequins. As is known from letters, memoirs, estate sales, and works of art, they were used by Rembrandt, Gainsborough, Thomas Sully, Sir Joshua Reynolds, and John Singleton Copley, among others, during the 17th and 18th centuries; by Frederick Leighton and his contemporaries in the 19th century; and by many modernist artists who had been trained in the academic tradition such as Courbet, Degas, and even Cézanne. Being merely studio apparatus, not surprisingly, artists only occasionally represented these mechanical assistants in drawings, paintings, or in scenes of the atelier—the latter, for example, depicted by Adriaen van Ostade (1610–1685) and Gustave Courbet (1819–1879).

The complete mobility of mannequins meant that they could be positioned naturally, allowing a convincing rendering of the body. Drawing the human figure was central to art education, but the primary value of these models until the late 19th century was not merely to depict the body but for drapery studies, an esteemed discipline that finds its source in the Neoclassical practice of copying casts of antique Greek sculpture.

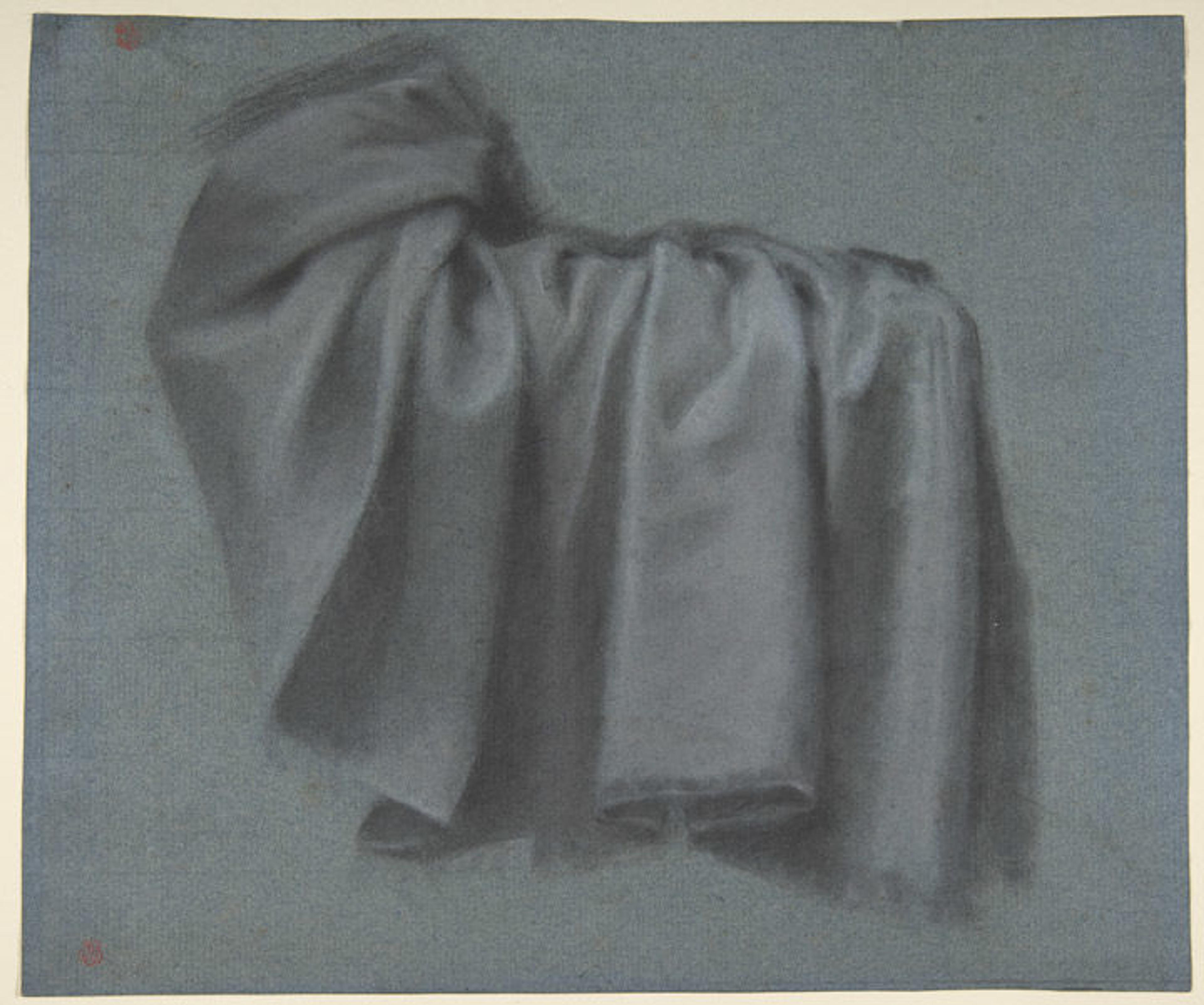

Pierre Paul Prud'hon (French, 1758–1823). Study of Drapery, ca. 1813. Black and white chalk with stumping on blue paper; 10 1/16 x 10 1/4 in. (25.5 x 26 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Guy Wildenstein Gift, 2008 (2008.44)

Life-size lay figures such as ours, rather than small-scale mannequins, were used to plan compositional arrangements and were particularly suited for this purpose. Fixed in place, the ample folds, weight, and sweep of the cloth registered a naturalistic effect by echoing the movement of the body; its volume further enhanced by chiaroscuro, the measured distribution of light and shadow, as seen in the Study of Drapery by Pierre Paul Prud'hon (1758–1823). To study the figure, the mannequin thus served as an ideal aid for the artist, allowing him to exercise the most important principles of his profession.

Never needing to take a break or a breath, the muted compliance of the mannequin also underlays its usefulness. Capable of holding a pose far longer than could be endured by a human model, these reliable stand-ins were of great value to portraitists. Serving as surrogates for the sitter, they allowed the artist to repeatedly draw, correct, and perfect his draftsmanship or brushstrokes, while for the patron they relieved the tedium of long posing sessions. To this end, the mannequin was often clothed in the attire of the sitter, one example being the coronation gown of Queen Victoria portrayed by Thomas Sully (1753–1872) in his painting of the monarch, in which her sumptuous attire was arrayed on a layman, a procedure to which he refers in his diary.

Right: Thomas Sully (American, 1783–1872). Queen Victoria, 1838. Oil on canvas; 94 x 58 in. (238.8 x 147.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Lent by Mrs. Arthur A. Houghton Jr. (L.1993.45)

To facilitate dressing and undressing, many lay figures, ours included, have detachable heads. While the readily positioned head with varied twists and turns served to convey the expressiveness of the body, its schematic countenance was of little interest to portraitists. The intent of their efforts was to capture the likeness and liveliness of the sitter directly from the living model, thus requiring the face to be painted in a separate session from the clothed body.

This mannequin was acquired by The Met in 2015 thanks to a partial gift from Ronald N. Sherr and leading gifts from Gregory Callimanopulos, Karen Cohen, Margaret Civetta, Marc and Rochelle Rosenberg, Marc Plonskier, and Jan and Marica Vilcek.

Related Link

Now at The Met: "The Body Hidden, the Body Revealed: Neoclassical Drapery Studies" (September 21, 2015)

Marjorie Shelley

Marjorie Shelley is the Sherman Fairchild Conservator in Charge of the Department of Paper Conservation.