Sophie’s World in danger: Living as though everything centres on our time is just as naive as thinking the Earth is flat

Two decades ago, a history of philosophy by an unknown Norwegian teacher became a most unlikely phenomenon. But how has time changed the writer? And how might he change his book now, if he could? Jostein Gaarder takes up his own story

Do philosophical questions remain the same for all time? Yes and no. Many of the fundamental questions about the nature of the universe and our place in it have occupied our thoughts for thousands of years. There is something about our world which demands investigation by philosophers. Human beings will never cease to wonder about their own existence.

New questions may also emerge from radical changes to our surroundings. One example is artificial intelligence. Will a robot ever achieve consciousness or self-awareness? How does the human brain function? What is the difference between a human and a machine? Another example is modern natural science. Age-old questions, about what plants and creatures are made of, are well on their way to being answered. Today we ask: what was the Big Bang and how did it bring about the necessary conditions for life?

However, by far the most important philosophical question of our time must be this: how are we going to save our civilisation and the basis of our existence?

From time to time I am asked a question. If I had written Sophie’s World today, is there something important I would have added? Is there something I would have placed more emphasis on? The answer is a resounding yes. If I were to write a philosophical novel today, I would have focused a lot more on how we treat our planet.

Climate change comes down to greed. The destruction of biodiversity comes down to greed. But greed does not trouble the greedy

It is strange to look back after only 20 years and realise that Sophie’s World doesn’t really address this question. The reason may be that over the course of these 20 years we have gained an entirely new awareness of climate change and the importance of biological diversity.

An all-important principle in the study of ethics has been the golden rule, otherwise known as the reciprocity principle: do to others what you would like them to do to you. Over time, we have learnt to apply this rule more widely. In the Sixties and Seventies, people came to realise that the reciprocity principle must apply across national borders, both to the north and to the south.

But the golden rule can no longer just apply across space. We have begun to realise that the reciprocity principle applies across time, too: do to the next generation what you would like them to have done to you, had they lived on the planet before us.,

It’s that simple. Love thy neighbour as thyself. Obviously this rule must apply to the next generation and to everyone who lives on the planet after us. They are human beings, too. Therefore, we should not leave behind a planet which is less valuable than the one we have enjoyed. A planet with fewer fish in the sea. Less drinking water. Less food. Fewer rainforests. Fewer coral reefs. Fewer species of animals and plants… Less beauty. Less wonder. Less splendour and happiness.

The 20th century has taught us that people need conventions and obligations which go beyond national boundaries. An important breakthrough was the UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, which was perhaps the greatest triumph of all time for philosophy and ethics. Because human rights were not granted to us by higher powers. Neither were they snatched out of thin air. They marked a full stop to a millennium-long process of advancement – or perhaps a semi-colon.

The question we are left with at the beginning of the 21st century is: for how long can we claim these rights without accepting they come with fundamental obligations. The time is ripe for a Universal Declaration of Human Obligations. It no longer makes sense to think about an individual’s rights and freedoms without also thinking about the responsibility of individuals and individual states – not least our responsibility to safeguard the rights of future generations.

At this very moment we are experiencing the consequences of man-made climate change. They are dramatic. However, opinion polls indicate that the people of this world are not particularly concerned. One day in the future, global-warming denial may be considered one of the greatest conspiracies of all time.

The era we live in is exceptional in every way. On one hand, we belong to a triumphant generation, which can explore the universe and map the human genome. On the other, we are the first generation seriously to lay waste to the environment. Human activity is draining resources and destroying natural habitats. We are changing our surroundings to such an extent that people think of our time as an entirely new geological era.

Huge volumes of carbon are contained in plants, animals, the sea, oil, coal and gas. The carbon is just itching to be oxidised and released into the air. The atmosphere on dead planets such as Venus and Mars is mostly CO2, and that would also be the case here if the Earth’s processes didn’t hold the carbon at bay. But from the end of the 18th century, fossil fuels have tempted us like the genie in Aladdin’s lamp. “Release us,” they whispered. And we gave into that temptation. Now we are trying to force the genie back inside the lamp.

If all the remaining oil, coal and gas on this planet is extracted and burnt, our civilisation will not survive. But many people and many countries see this as their divine right. Why shouldn’t they use the fossil fuels on their land? Why shouldn’t countries with rainforests chop them down? What’s the difference? What difference will it make to CO2 levels or to biodiversity if one country stops while the rest carry on?

Over the past few centuries, most people here in Norway have been lifted out of poverty. The same is true in many regions of the world. We should not forget that. But this prosperity has come at a high price, a debt we are only now beginning to pay off. Before the Industrial Revolution, the atmosphere contained 275 CO2 parts per million. At the moment of writing, that figure is 400 ppm and it is still rising. Devastating climate change is unavoidable at this rate. Sooner or later we must attempt to return to pre-industrial CO2 levels.

In pictures: Changing climate around the world

Show all 15According to Dr James Hansen, considered by many to be one of the world’s leading climate researchers, we must – initially at least – get this level down to 350 ppm. Only then can we feel reasonably secure that we will escape the worst catastrophes for this planet and for our civilisation. But the figure is not going down. It is going up.

If we are to save biodiversity, we need to revolutionise our thinking. Living as though everything centres on our time is just as naive as thinking the Earth is flat. Our time is no more significant than future times. It is only natural that our time is the most significant to us. But we cannot live as though our time is also the most important one for those who come after us. We must respect future times as we respect our own time.

In relationships between individuals and between nations, we have emerged from our “natural state”, characterised by the survival of the fittest. But when it comes to the relationship between generations, unbridled lawlessness still reigns.

Everyone has the right to practise their beliefs, and everyone has the right to hope that our planet can be saved. But that does not guarantee that there will be a new heaven and a new earth awaiting us. It is unlikely that supernatural forces will bring about a Judgement Day. But it is inevitable that we will be judged by our descendants.

Climate change comes down to greed. The destruction of biodiversity comes down to greed. But greed does not trouble the greedy. History is our witness. But were we to live by the principle of reciprocity, we would only use non-renewable resources if we could pave a way for future generations to have the same quality of life without those resources.

The ethical question is not difficult to answer – what is difficult is living by the answer. But if we forget our descendants, they will never be able to forget us.

The question of how widely we should apply the reciprocity principle comes down to identity. What is a human being? Who am I? If I were merely myself – that is, the body sitting here writing – I would be a creature without hope. But my identity goes deeper than my own body and my own short time on Earth. I am a part of – and I take part in – something which is bigger and greater than myself.

Humans tend to have a local and short-term sense of who they are. We used to have to scan our surroundings, wary of dangers and prey. That gives us a natural tendency to defend ourselves and protect our own. But we do not have the same natural tendency to protect our descendants, not to mention species other than our own.

Favouring our own genes lies deep within our nature. But we don’t have the same instinct to protect our genes four or eight generations down the line. That is something we must learn – just as we had to learn to respect human rights.

Ever since our species emerged in Africa, we have fought a determined battle to prevent our branch of the evolutionary tree from being cut off. That battle has been successful, for we are still here. But we have become so prosperous that we are threatening the basis of our own survival. We have become so prosperous that we are threatening the basis of every species’ survival.

As clever, vain and inventive as we are, it is easy to forget that we are simply primates. But are we really so clever if we put our cleverness and inventiveness ahead of our responsibility for the future of the planet?

No longer can we think only about one another. The planet we live on is an essential part of our identity. Even if our species is destined to die out, we still carry an important responsibility for this unique planet and for the nature we leave behind.

Modern humans think we are almost entirely shaped by our cultural and social history, by the civilisation which produced us. But we are also shaped by our planet’s biological history. There is a genetic heritage as well as a cultural one. We are primates. We are vertebrates.

It took billions of years to create us. Billions of years to create a human being! But are we going to survive the next millennium?

What is time? First we have the horizon of the individual, then of the family, of culture and of literary culture, but there is also geological time – we come from tetrapods that crawled out of the sea 350 million years ago – and finally, there is cosmic time. Our universe is almost 13.7 billion years old.

But in reality, these periods of time are not as distant from one another as they may seem. We have reason to feel at home in the universe. The planet we live on is precisely one third of the age of the universe, and the class of animals to which we belong, the vertebrates, has existed for a mere 10 per cent of the time our solar system and life on Earth have existed. The universe is no more infinite than that. Or conversely: our roots and our kinship are intricately and deeply woven into the universal soil.

Human beings may be the only living creatures in the entire universe who have a universal consciousness. We have a staggering sense of the immense and mysterious cosmos we are part of. Therefore, not only do we have a global responsibility to save our planet. We have a cosmic responsibility.

This is the foreword to the 20th anniversary edition of ‘Sophie’s World’ (Weidenfeld & Nicholson, £8.99) published 8th October 2015. Translation © Paul Russell Garrett 2015 is published 8th October 2015.

Sophie's World: the unlikely bestseller

By John Walsh

As fiction aimed at a global young adult audience go, it’s hardly up there with The Hunger Games, is it? You’d think only unusually sober-minded teenagers would rush to buy Sophie’s World: A Novel about the History of Philosophy. Yet the thick, 518-page tome with the dismayingly flat chapter headings (“The Pre-Socratics”; “Descartes”) was the world’s biggest-selling novel in 1995. Since then it’s sold 40 million copies and been translated into 60 languages.

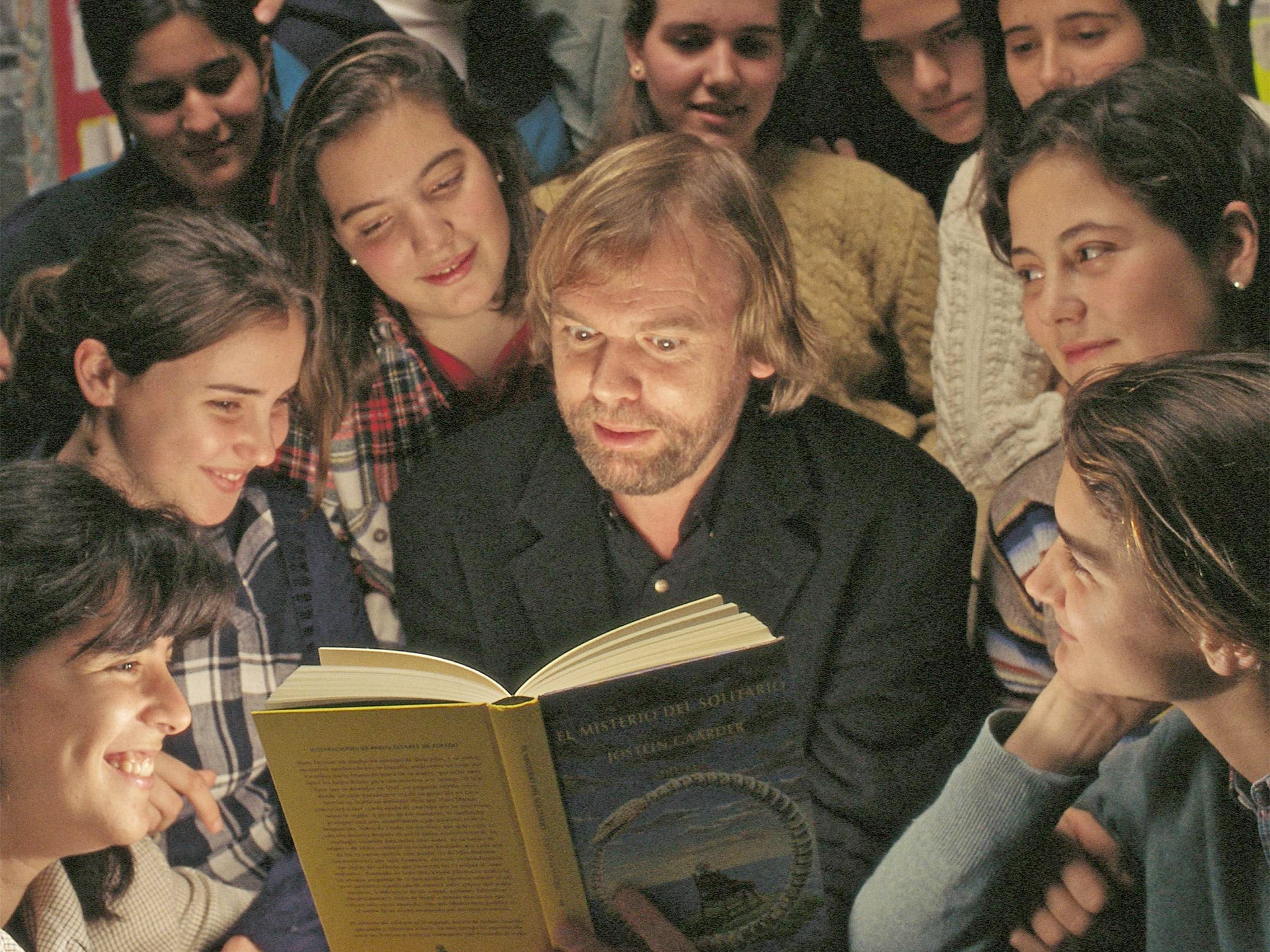

Its author, Jostein Gaarder, was an unknown, 43-year-old Norwegian high school teacher in the town of Bergen, with a wife called Siri and two sons, when he hit the jackpot with his third book for children (the previous ones were called The Solitaire Mystery and Through a Glass, Darkly). He told the press he’d expected to appeal to a specialist readership – schoolkids who know their categorical imperative from their logical positivism. He was wrong.

The book starts with 14-year-old Sophie Amundsen returning from school to find two letters for her. Each asks a question: “Who am I?” and “Where does the earth come from?” An unusual Scandanavian pubescent, Sophie feels a stirring in her brain as she contemplates the world of philosophy. She also finds in the mailbox a letter from one Albert Knag, addressed to his 15-year-old daughter, Hilde Moller Knag. Sophie has no idea who they are. While puzzling over the day’s mysterious post, she finds a course in philosophy in a wad of papers and starts taking philosophy lessons, from Socrates to Sartre, from a professor called Alberto Knox.

Many reviews wondered how young readers would endure the screeds of opaque jargon in which some chapters were couched, and some book-world cynics attributed the success of Sophie’s World to parents hoping to give their teen offspring a fast-track education in thought. The BBC screened a version of the book by Paul Greengrass (later to direct two of the Bourne films) starring Jim Carter (later more famous as Carson in Downton Abbey) as Alberto Knox, and Twiggy as Sophie’s mother.

Gaarder himself became increasingly politicised. He campaigned for environmental causes (the main preoccupation of his new Introduction) and, in 1997, established an annual $100,000 Sophie Prize for individuals or foundations which promote sustainable development. In the next 15 years, it awarded $1.5m in prize money. More controversially, Gaarder wrote polemical articles in the Norwegian press in 2006, about the plight of Palestinian refugees. He called Judaism “an archaic national and warlike religion” and was attacked for anti-Semitism. But 20 years after he first startled the book world, Gaarder is introducing a whole new teen generation to something more lastingly important than Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone. Namely, the philosophers.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments