It doesn’t take a third eye to see that, at long last, Americans seem primed to turn on. If you’ve heard yourself utter the phrase “plant medicine” when what you mean is “shrooms,” if you’ve found yourself absently Googling “ayahuasca retreats” the way you used to look for beach getaways, if you’ve got a friend who flew across the country to take a “heroic dose” of psilocybin in the care of a shaman and you felt the sharp prick of jealousy…you are, well, hardly alone.

We’re talking senior citizens (“…psychedelics are wasted on the young,” author and mushroom mainstreamer Michael Pollan told AARP) and moms (“Magic Mushrooms Helped Me Cope With Postpartum Depression,” writes Good Housekeeping). We’re talking business executives looking for creative inspiration, and guys who wouldn’t be caught dead in a tie-dye searching for a little magic in their lives, be it a psychological breakthrough, a mystical experience, or just a mind-blowingly bananas weekend.

I’m one of those looking for a little magic. Twenty-five years ago I left my somewhat steady diet of mushrooms, blotter, and MDMA behind me (kids, career, fear I’d been pushing my luck). But lately, along with the rest of America, I’ve been itching to hop back on the psychedelic horse after years of looking longingly at the saddle.

And guess what? My time has come. But I’m not deep in the Peruvian jungle holding a feather and chanting in a language I don't understand. No, I find myself on a Santa Monica sidewalk, staring at a brick building—wedged between a hot-yoga studio and a clean-ish looking youth hostel—home to Reality Center, which offers hour-long psychedelic experiences.

But there’s the twist: The psychedelic experiences they offer are entirely without psychedelics. Which is to say without the drugs. Without the cow-shit taste of mushrooms. Without the what’s-actually-in-this? hand-wringing over a capsule of MDMA. Without the puke-fest of ayahuasca or the I’ll-get-back-to-you-in-12-hours dice-roll of LSD.

I am here to test-drive the Reality Center, but also to catch a glimpse of the coming storefront psychedelic revolution.

The Reality Center promises it can induce a psychedelic state digitally, flooding the senses with a deeply researched, personalized (and proprietary) recipe of synchronized light, sound, and vibrations. I’m skeptical but game. My press-shy friend, whom I’ll call Felicity, is along for the ride. The center’s mission statement reads, “To provide technology that facilitates positive change for humanity,” and speaking honestly, Felicity, who’s had a bumpy couple of years, would very much like this session to result in positive change, if not for all humanity then just for herself. She is more hopeful than I am.

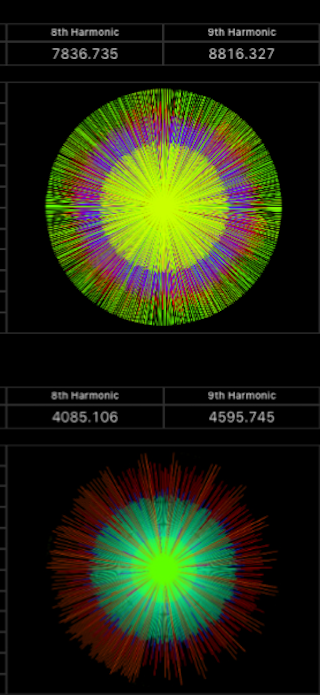

In we go. The space is soothingly darkish, lit by a large LED screen dancing with colors, shapes, and mandala-ish patterns. We’d been offered a couples session but had decided to explore on our own (the center charges $249 for an hour but discounts are available) and compare notes after. I go first and head into a smaller darkened room with a dentist-style chair and a luminous screen. This is the vocal analysis room, and I lay back as Tarun Raj, 41, Reality Center’s president and co-founder, speaks in the warm, comforting tones of my meditation app; after asking me to close my eyes and take the requisite three deep breathes, he suggests that I envision my “happy place.” As I describe my happy place (none of your business), my voice is being analyzed by some cool software, and the screen in front of me sparks to life with color-soaked bar charts that rise and fall as I speak.

The technology used by Reality Center was developed over the course of some four decades by Don Estes, a self-taught researcher, inventor, and high-tech tinkerer who used to pal around with Timothy Leary, Ram Das, and John Lilly, the neuroscientist and psychonaut (and dolphin researcher!) upon whom the film Altered States was based. Estes, 73 years old and the center’s chief science officer and co-founder, tells me that after his own first psychedelic experience, he “wanted to live in that space every day” but realized it wasn’t feasible, so, he says, “I devoted my life to coming up with a way to achieve that state without having to pop the pill.” In the years that followed, Estes developed his theory of Sensory Resonance: When the senses are hit with exactly the right levels of synchronized light, sound, and vibration, a person’s brainwaves can be nudged into a meditative, even psychedelic state, and the person’s autonomic nervous system can be “reset.”

And the reason my voice is being analyzed? Because the voice, Estes tells me in his calming Georgia drawl, holds the key to “what your body needs.” Those charts and mandalas are graphic representations of my emotional strengths and “needs.” In a moment, this data will be shared with the technology in the next room and the lights, sounds, and vibrations washing over my senses will be specifically calibrated to respond to those needs. “If you wanted to tune up a musical instrument,” Estes explained later, “you’d start twisting the wires with a tuner until you got them in line. For us, it’s a matter of separating the voice into frequencies so that we can actually see what’s going on within a person. Then we use the technology to help balance that. We’re not really finding what's wrong and fixing it,” he says. “We’re identifying what's right and enhancing it.”

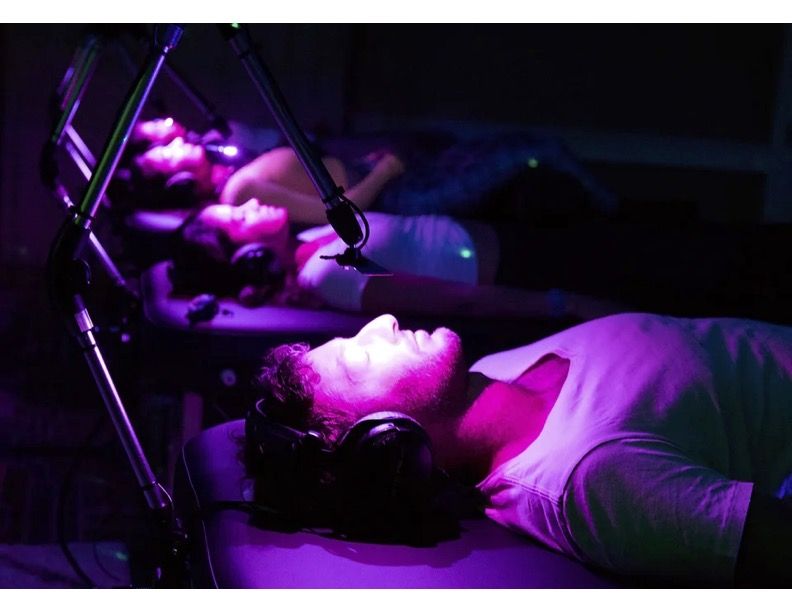

I’m led into the next room by 41-year-old COO and co-founder Jonathan Chia, and then onto the WaveTable, where I will pass the next hour. The Vibrasound™ Vibrotactile WaveTable ($19,999) is a remarkable instrument in its own right: Filled with a liquid mineral substance that, Chia says, “mimics human tissue fluid,” the WaveTable allows you to feel as if you’re both floating and supported at the same time. The bed vibrates at rates ranging from half a hertz—a hertz being one on-off cycle—to 250 hertz per second. I slip the headphones on. Close my eyes. “The deeper you breathe,” Chia says, “the higher you fly.” So I breathe really, really deep. And then it begins.

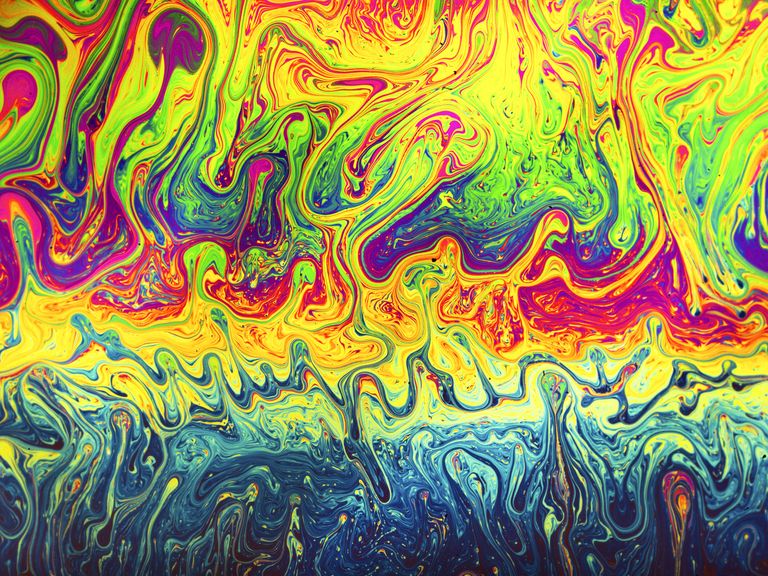

Light hits my eyelids. It pulses faster and faster, and what I see on the inside of my lids reminds me of those marching brooms in Fantasia. Unlike with, say, mushrooms or LSD, there is no stare-at-your-hand moment of wondering whether the drug is kicking in. It’s like a light switch: Suddenly, my entire visual field washes Rothko yellow then purple, and then, just as suddenly, everything fractures and fractalizes. It’s fucking gorgeous. The light keeps flickering (up to 40 hertz per second) and, as the “sound bath” engulfs me, I feel like I’m walking through the kaleidoscope I had as a child, surrounded by colors so crisp and clear and close they feel touchable. At this point, I might be a minute or two in; soon, I will completely lose track of time.

A funny thing happened in the years since my youthful drug-addled adventures: Psychedelics have become legit medicine. The research pouring out of name-brand universities is clear on this. Psychedelics can create connections between areas of the brain that don’t usually “talk” to each other while also disrupting the sometimes circular, repetitive thinking that can lead to, say, paralyzing anxiety. By “rewiring” the brain, psychedelics can help with alcohol addiction, depression, OCD behaviors, anxiety, and trauma, and can even calm the existential fears of terminal patients.

“The culture is finally catching up with us,” says Estes, who had his own a-ha moment in 1972 while tripping atop a stack of Marshall amps at a concert. With cannabis dispensaries destigmatizing over-the-counter weed buying, the Reality Center stands at the forefront of the storefront psychedelic tripping trend. Referring to itself as a mainstream-friendly “state-of-the-art sensory wellness center,” it’s easy to imagine the psychedelically curious wandering in during a lunch break. “A lot of our clients,” Estes says, “are people who want to try psychedelics but are afraid.” The center allows them to safely dip their toe into the swirling waters of the mind, then grab a hummus wrap and head back to the office.

In addition to catering to the curious masses, the center focuses on helping former soldiers ease their PTSD. So far, some 350 veterans (from wars in Afghanistan, Iraq and Vietnam, even a 93-year-old WWII vet) have received treatments, most at no charge. Chia himself served a 15-month tour as a machine-gunner in Iraq. “I lost 16 friends over there,” he told me, “but many, many more than that when we got back, due to drug overdoses or suicide.” While there are no studies or hard numbers, Chia tells me that, anecdotally, Reality Center treatments have proven extremely helpful for veterans.

The visuals intensify, an incredible, unpredictable lightshow playing on the endlessly deep movie screen of my visual field. When the sound of tom-toms begins galloping into the headphones, I’m gifted a shade of blue I’ve never seen before, so pure, so unique it defies description. The colors and shapes shatter, reassemble, morph from one intricate pattern to the next. At one point—by now the concept of “time” has vaporized—I feel like I’m deep in a churning tie-dye sea, washing this way and that until the patterns turn into coral which then turn into the crenulations of a brain. Maybe my brain. Then Zwooosh!! I’m streaming through space as if Han Solo had just smashed the lightspeed button.

And yet. And yet while the visuals are indeed exquisite, I’ve always felt there was more to a psychedelic experience than eye candy. I find myself missing the mental knee-buckle that occurs during a peak mushroom moment when one’s long-held assumptions about how the world works bend back on themselves in a way that makes you see something from entirely new perspective. Like, say, the instantaneous understanding that the shaft of golden light you’ve been staring at is actually filled with time. I miss the snowstorm of weird ideas, the swell of four-dimensional emotion.

Felicity wraps a few minutes after I do and meets me in a sort of “morning after” room where we have a post-game debrief with Estes, Raj, and Chia. We say our goodbyes, leave the ho-hum brick building, and walk into the touristy wilds of Santa Monica.

Out on the street, colors seem richer, objects more defined, and I feel lighter—mentally but also physically. My stride has a little float. Felicity says she enjoyed the experience and, like me, feels as though her nervous system is now simultaneously revved and relaxed. “It reminded me of Pink Floyd laser shows back in high school,” she tells me. “It’s gorgeous and totally immersive but once the lights come on, it’s over. I don’t feel a big realization living within me.” She’d been hoping for something, in her words, “more profound, more transporting, more transforming.” This may have been an unfair ask for a single, hour-long session without the talk therapy, not provided by the center, that often accompanies longer-term treatment, but Estes tells me that people frequently report more dramatic “trips” than Felicity and I experienced, with positive effects rippling gently through their lives for a few days. In fact, Chia, the Iraq vet, was so deeply transformed after a single session that he was inspired to join the company. “I’ve experienced so much trauma,” he told me. “Even though I wasn’t at war any more, my body was stuck in fight-or-flight mode. I’d forgotten how to turn it off. [After that first session], the ego and anger I had went away. And I finally felt at peace.”

While Felicity and I stroll Santa Monica’s sun-soaked streets, I find myself thinking about the Reality Center’s place in the new culture building around psychedelics. What, I wonder, are the upsides and downsides of the mallification of psychedelics? Felicity, more sensitive and evolved than I will ever be, likes the fact that a mind-expanding experience may soon become as accessible to your average person as an Auntie Anne’s pretzel. The more people helped, the better. No stigma. Nothing illegal. What’s wrong with feeling amazing during your lunch hour and then returning to work a little more chill, a little more inspired?

She’s right. Nothing wrong with that. But it also strikes me that when a psychedelic experience starts to look more like drop-in massage therapy, maybe something—something special—is lost. For me, a key aspect of a psychedelic trip was that you were committing to a journey, one with an unknown destination, unknown route, and unknown intensity. That leap of faith, in and of itself, was both part of the ritual and part of the growth.

I was curious to find out what Jesse Jarnow thinks about all this. Jarnow wrote the book “Heads: A Biography of Psychedelic America,” which traces how psychedelics have moved in and out of the culture. He was quick to point out that the relatively recent “reframing of psychedelics as a healing thing, as a wellness thing” has made them more respectable in a good way, giving people the feeling that, in the hands of a pro, “you're not going to fall out of the roller coaster and die.” At the same time, as someone who’s studied the underground culture, economy, and folklore that evolved around psychedelics, he dreads their coming corporatization and “enshittification.”

With respect to the type of experience offered at the Reality Center, which Jarnow has not yet tried, he says, “Drugs are an easy reference point, I get it. But psychedelics are still the most powerful way to have a psychedelic experience, so maybe frame this experience as something different, something newer.” That felt spot-on but it’s a bit of a high-wire act: Yes, if Felicity and I hadn’t been expecting a true psychedelic experience, we’d have been ecstatic with our hour dance among ferociously beautiful visuals…and yet, to be honest, if the center hadn’t advertised it as a psychedelic experience, we might not have shown up in the first place.

Now standing with Felicity on the bluffs high above the silvery Pacific Ocean, I get a vivid flash of memory and it’s like I’m looking through time itself: Down there, on that wide sand beach, I once took a hit of Blue Unicorn blotter with a few of my closest high school friends. It was the summer after senior year and I recall our laughter and that someone handed me a tropical fruit Life Saver that tasted better than anything ever had and that we spent a ridiculous amount of time trying to figure out how many grilled cheese sandwiches we’d have to sell to get to Philadelphia. But as the sun began to slip below the horizon line, our inane chatter stopped and the four of us silently fixated on the long, anthropomorphic streaks of pink and red that, all these years later, I can still remember whispering the secret of the universe to us, and us alone.