Scattered throughout western Crete lie eight exquisitely decorated fourteenth-century Byzantine churches. They inhabit different landscapes, and can be found tucked away in ravines, clinging to cliff sides, and nestled amongst the olive groves or betwixt the few homes of a small village. Through their late medieval fresco programs, these chapels offer an unparalleled glimpse into the lives of medieval peasantry who built them, but they also preserve the legacy of one of the few known, named Byzantine painters, Ioannis Pagomenos, who worked as an artist in Crete in the first half of the fourteenth century.

“Salvaging Crete” identified a representative sample of monuments based on their unique artistic significance, particularities of location, and distinct state of disrepair and/or conservation, and set out to thoroughly record their fragile architectural frame and painted decoration, as well as to generate a stable archive of integral value to Byzantine and Hellenic studies. The study’s churches include:

- George, Komitades, Sfakia, Chania, 1313–1314

- Nicholas, Moni, Selino, Chania, 1315

- Panagia, Alikampos, Apokoronas, Chania, 1315–1316

- George, Anydri, Selino, Chania, 1323

- Nicholas, Maza, Apokoronas, Chania, 1325–1327

- Archangel Michael, Kavalariana, Selino, Chania, 1327–1328

- Panagia, Kakodiki, Selino, Chania, 1331–1332

- Panagia, Prodromi (Skafidia), Selino, Chania, 1347

Small chapels such as these were the result of predominantly rural Byzantine communities and often formed the center of village life and ritual religious practice. In the fourteenth century, Crete was under Venetian rule, particularly visible in the coastal cities of Chania and Heraklion (medieval Candia), but the island retained a strong Orthodox Greek community throughout. While the interior decorative programs of village churches generally reflected Byzantine iconography, they also reveal the local residents’ immediate concerns. Communities reached out to artists to complete the interior fresco decoration and, while most of these artists’ names are lost to us, a few eastern Mediterranean painters in the late medieval period signed their work, including Pagomenos. These chapels’ decoration provides a wealth of insight into the stories, struggles, and anxieties of the lower strata of peasant society, but also into shifting perspectives on the status of the artist and the importance of painting between Byzantium and the emerging Renaissance in Italy. Located at a cultural crossroads in Crete, Pagomenos and his signed work shed light on a pivotal early moment in the artistic transition of the medieval period to the early modern Renaissance, during which painting asserted a place among the liberal arts and the artist claimed status as a creative and accomplished intellectual with individuality and personal style.

Documentation of Pagomenos’s work, and the monumental painting of Byzantine village churches more generally, lags behind that of the churches of medieval Greek cities. While Pagomenos’s images provide an unparalleled vantage point from which to explore Byzantine and early modern Greek art and culture, only very limited aspects of his remaining frescoes have been catalogued. Adding cause for alarm, the precious visual record that these churches contain is threatened by a lack of monitoring and resources to support conservation, as the elements continue to take their toll on these aging structures. In response, this project conducted a rapid assessment of the current state of conservation and management of the churches, as well as a documentation campaign. The team measured and photo-documented the architecture and decorative programs, with the aim of creating a record of Pagomenos’s contribution before the frescoes further deteriorate or are lost in entirety.

Over a period of three weeks, our interdisciplinary team worked closely with local heritage management authorities to complete the survey and data-gathering phase of this project. Documenting and mapping of conditions is the starting point for any conservation process, especially for heritage at imminent risk. Byzantine art historians, Dr. Cristina Stancioiu (William & Mary) and Dr. Naomi Pitamber (Pennsylvania State University), completed the photo-documentation of the decorative programs and architecture. Measurements, preliminary drawings, and current physical conditions were recorded by architect and conservator, Tiffin Thompson (HOK). Dr. Helen Human (Washington University in St. Louis), team anthropologist and cultural heritage management specialist, conducted semi-structured, open-ended interviews with local stakeholders to collect baseline data on site management and development and environmental pressures. These included conversations with representatives of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Chania, the state entity responsible for planning and executing conservation, restoration and promotion for monuments and archaeological sites, local clergy and residents, landowners, and individuals involved in local tourism and businesses.

The team’s documentation approach required the development of a process that would gather the data required by multiple disciplines—art and architectural history, conservation, architecture, and cultural heritage management. Additionally, recording techniques should match the needs, skills, and technology available to those ultimately responsible for managing and caring for sites (Percy et al. 2015).K. Percy, C. Ouimet, S. Ward, M. Santana Quintero, C. Cancino, L. Wong, B. Marcus, S. Whittaker, and M. Boussalh, “Documentation for Emergency Condition Mapping of Decorated Historic Surfaces at the Caid Residence, the Kasbah of Taourirt (Ouarzazate, Morocco),” ISPRS Annals of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, II-5/W3(5) (2015): 229–34. With this in mind, the team aimed to develop a low-cost, yet effective technique, with an eye towards creating a rapid recording approach that could be implemented widely in order to document the monumental painting of other Byzantine village churches where painted decoration is rapidly decaying. Prior to departure, the team prototyped a documentation process, and during fieldwork it was possible to test and refine this methodology.

A conservator from the Ephorate of Antiquities of Chania accompanied the team to each church site. Following geo-location, recording began with a 360-degree photograph of the interior of the church with its current assemblage of furniture and moveable religious objects in situ. While these sites are significant from a historical perspective, it is vital to remember that they are also sites of worship and pilgrimage. All of the churches in this study are, at least occasionally, used for religious services, festivals, or on saint’s name days. Thus, they form a part of the fabric of the lives of those who reside in the vicinity of these chapels.

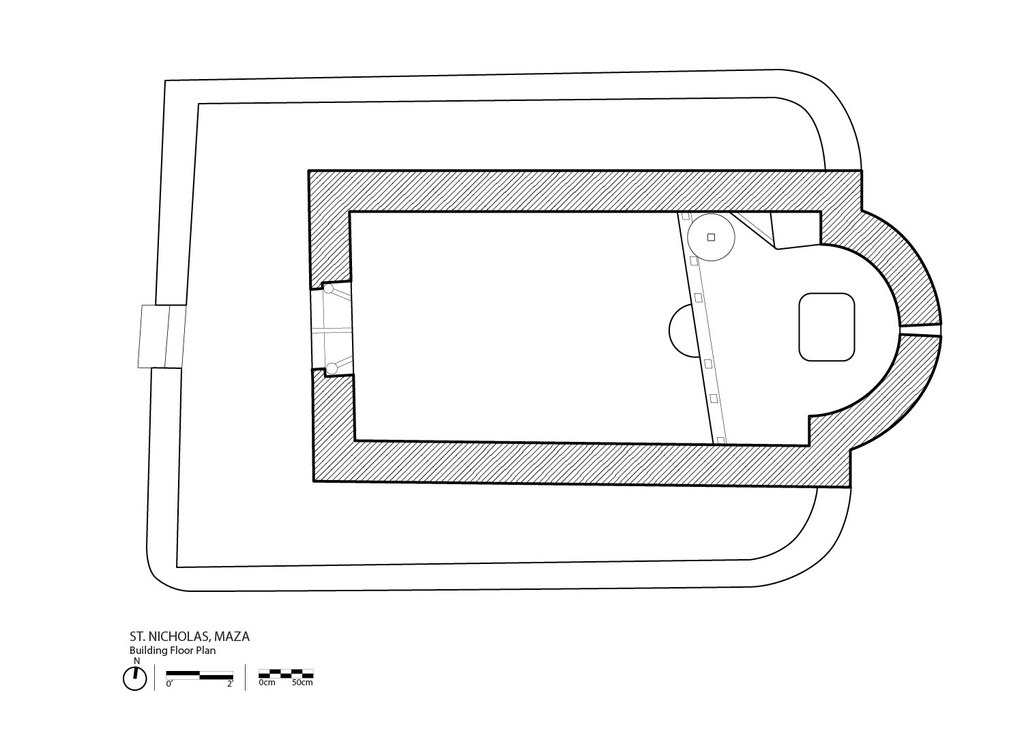

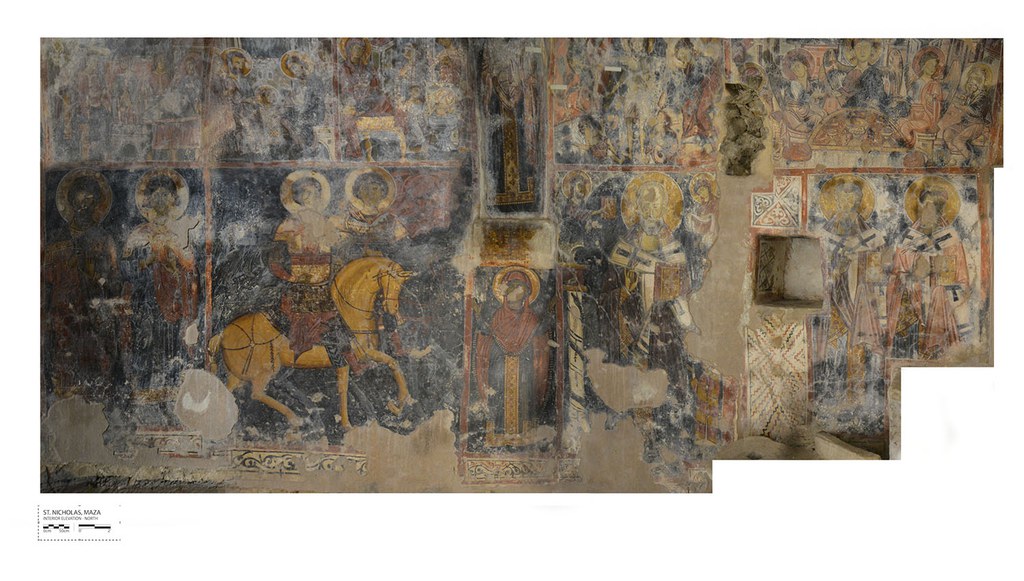

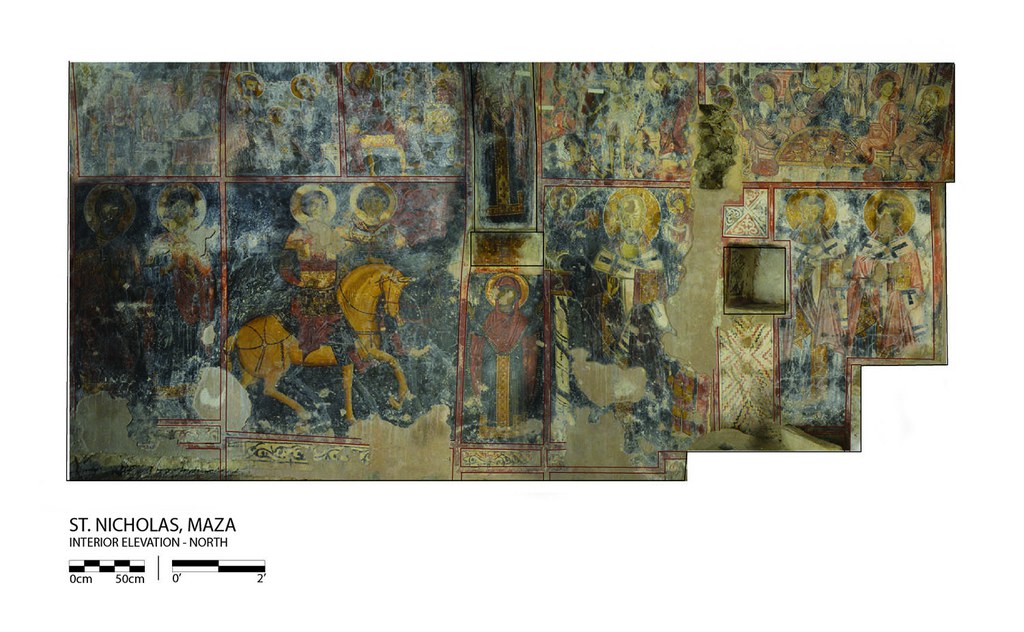

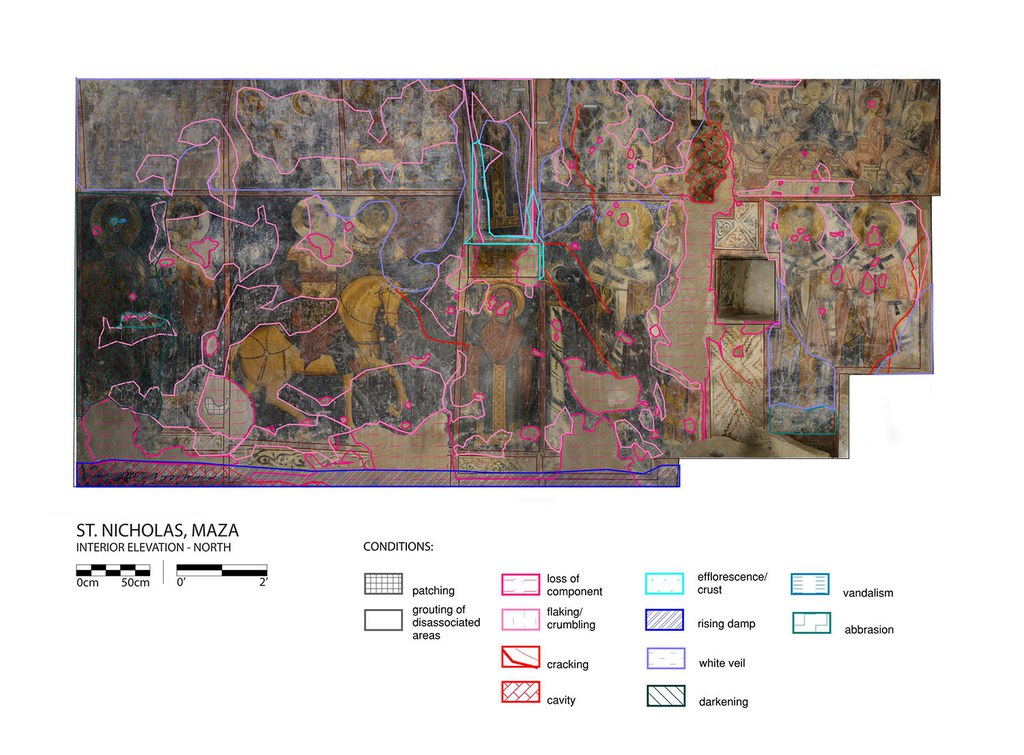

With permission, our team removed furniture and large icons resting on the fresco walls from the church. Art history photography of the frescoes then took place, while the team architect drew the interior and exterior elevations. Interior and exterior building measurements were then annotated on the elevation and plan drawings. Meanwhile, the team took interior measured photography—by far the most time-consuming aspect of the process. These images were taken at systematic intervals with a consistent step-back from the wall and camera leveled along three axes. In order to avoid distortion along the perimeter of the images, the team opted not to use an overly wide camera lens. Owing to the small scale of the churches, this meant a larger number of photographs were required in total. During post-processing, these images are being stitched together and form the basis for measured elevation drawings and for the mapping of conditions of the frescoes. Simultaneously with the measured photography, the team conservator noted conditions on the interior and exterior of the building and photographed the exterior of the building, including the roof. The team anthropologist photographed and surveyed the surrounding site area, engaged with local community members, and conducted semi-structured interviews. These conversations proved extremely useful for understanding some of the observed conservation interventions, as well as damage to the frescoes. Additionally, participant observation and interviews with conservators from the Ephorate and local business owners, residents, and priests helped to enlighten the functioning of the management system in practice. Upon completion of the documentation, the team returned all moveable objects to their original places within the church.

The survey revealed that exposure to water is the most pressing concern, with the majority of active conditions arising from wet/dry cycling, high humidity, and other water-related issues. All eight chapels are rubble masonry construction featuring a barrel vault ceiling and roof made from terra-cotta tiles. While all are intact, with roof and door to shield from direct contact with the elements, problems with drainage at the foundation, roof run-off, and major and minor cracking in the walls allow for water intrusion and extensive fresco loss. Active conditions observed include capillary moisture in the walls (otherwise known as rising damp), salt crystallization damage, flaking of paint, calcite deposits that form a white veil, crumbling, water staining, and the disassociation or detachment of the fresco from the wall. Conditions observed that relate to usage include abrasion from chairs, icons, and other furniture rubbing against the walls, soiling due to smoke exposure, isolated vandalism of figures, and loss due to the replacement or introduction of an iconostasis. Bio-growth, such as the growth of broad-leaved plants, lichens, mold, and fungi and insect infestation, was also observed to contribute to loss. Foundation settlement is a compounding factor at many of the sites. Caused by poor soils, climate, inadequate drainage at foundation, and poor soil compaction, foundation settlement contributes to cracking and water infiltration.

Repair and conservation work to consolidate the frescoes has been carried out to some extent at every structure included in this study. The churches of St. Nicholas at Maza, the Panagia at Alikampos, St. Nicholas at Moni, and the Panagia at Prodromi have seen previous conservation campaigns during which the walls appear to have been cleaned of soiling and calcite buildup, undergone desalination treatment, areas of loss had been edged with mortar, and areas of fresco detachment were consolidated with grout or glue. Without these preservation efforts, the state of conservation of the churches would be much worse.

“Salvaging Crete” demonstrates the importance and feasibility of a truly interdisciplinary, digital humanities project aimed at bringing awareness to a neglected corpus of incalculable historic value, reassessing cross-cultural and pan-Mediterranean cultural developments, examining current cultural heritage and preservation practices, and developing international collaboration.

Our results demonstrate the usefulness of a documentation process that can be implemented inexpensively and within a limited timeframe, especially for the recording of small-scale decorated spaces.