Cary Grant’s charm was legendary, but his best character was actually himself

Loading...

Alfred Hitchcock once remarked that likability was not something actors could fake. According to author Scott Eyman, the director added that there was “only one actor in the world so formidably skilled that he could fake a charm he did not in fact possess.”

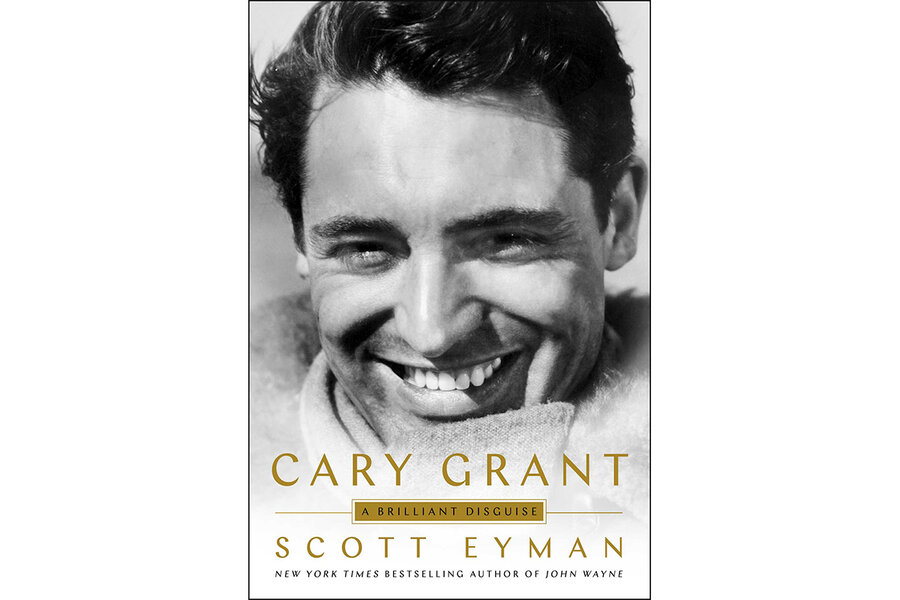

The star Hitchcock had in mind is the subject of Eyman’s richly entertaining new biography, “Cary Grant: A Brilliant Disguise.” The book offers ample evidence that many who knew Grant were convinced his charms were genuine. But Hitchcock’s piercing assessment jibes with Eyman’s thesis that the legendary leading man was, even more than most Hollywood stars, a pure invention. The actor admitted as much himself: “He’s a completely made up character and I’m playing a part.”

Grant was born Archibald Alexander Leach in Bristol, England, in 1904, the child of working-class parents. His early years were miserable. His alcoholic father had his erratic mother institutionalized when Archie was 11 and allowed the boy to believe she had died.

It’s remarkable that from this disadvantaged background the uneducated Grant came to be seen as the epitome of aristocratic grace. Part of the explanation lies in his dashing good looks. He worked hard to cultivate an elegant style and an acerbic wit, always with a slight air of detachment.

Eyman covers Grant’s films in lavish detail, sometimes too much detail (at more than 500 pages, the book is at least 50 pages longer than it needed to be). Beginning in the late 1930s Grant had an impressive run of hits whose highlights include “Bringing Up Baby,” “His Girl Friday,” and “The Philadelphia Story.” Some of his best work was with Hitchcock, who was able to draw out a darker side of the actor in “Suspicion,” “North by Northwest,” and “To Catch a Thief.” The two had a productive and friendly partnership, despite the director’s later harsh appraisal.

Referring to the actor’s public persona, Eyman describes “the essential duality of Grant’s character – ardently pursuing fame while resisting exposure.” This resistance appears to be just as true of his intimate relationships, which developed a pattern of frenzied pursuit followed by withdrawal. The actor was married five times. He did not become a father until late in life. He stopped making films and appeared to derive more pleasure and joy from parenthood than he ever had from acting, which had never failed to make him anxious.

Eyman writes in lively prose that benefits from his command of classic Hollywood. He treats his subject with compassion. Noting Grant’s insecurity over his performance in one of his final films, Eyman observes, “An actor’s life is emotionally perilous, right to the end.”

Grant was aware of two rumors that swirled around him throughout his life: that he was gay and that he was cheap. He denied both. Of the former, which centered around his relationship with actor Randolph Scott, his off-and-on housemate, Eyman notes that there is “plausible evidence to place him inside any sexual box you want – gay, bi, straight,” but the author comes to no firm conclusion.

The latter claim is easier to prove. Several friends recalled the wealthy Grant regularly sticking them with the check at restaurants; others spoke of his billing them for laundry and incidentals after they’d been his houseguest. Even the formidable Katharine Hepburn once after staying at his home “sent him a check for $1.81 to pay for the phone calls for which Grant obviously expected to be reimbursed,” Eyman writes.

She must have nevertheless found him charming. They remained friends until the end.