Enter the Dragon, Exit the Stereotypes: Bruce Lee and the Most Influential Martial Arts Movie Ever (Preview)

by Jarek Kupść

In the opening fight scene of Enter the Dragon, Bruce Lee doesn’t just make an entrance—he explodes onto the screen. Lithe and lightning fast, clad only in black trunks, Lee cuts an instantly iconic figure. He arrives with a vengeance and exits with a smile. But that friendly duel with a fellow Shaolin monk (Sammo Hung) was the last scene Lee would ever film in his tragically short life. By the time Enter the Dragon premiered in America fifty years ago, Bruce Lee was already gone.

Regarded by many as the best martial arts film of all time, Enter the Dragon is certainly the most influential. Considering inflation, it remains the most profitable entry in the genre. Not only did Enter the Dragon spawn the Occidental fascination with martial arts cinema, but the film also helped to promote Asian culture at large. Perhaps most importantly, however, it gave the rest of the world its first modern Asian idol. The recent phenomenal success of Everything Everywhere All at Once would not be possible without Bruce Lee having shattered the glass ceiling with a flying kick in August 1973.

Box art for new 4K UHD + Blu-ray 50th anniversary release of Enter the Dragon.

The last time an Asian actor had been given top billing in Hollywood before then was a 1942 film, The Lady from Chunking, starring the Chinese American performer Anna May Wong. The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor rekindled the Yellow Peril sentiments, which hadn’t exactly been dormant in the United States since the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act (repealed only in 1943). During World War II, over 125,000 Japanese Americans were relocated to internment camps throughout the country.

In 1950, America engaged in the war between North and South Korea in support of the autocratic and U.S.-friendly South. Hollywood responded with a slew of Korean War films, mostly propagandistic, action-driven fare. It was nevertheless rare to see any “friendly” South Korean military personnel directly involved in screen combat. The mortal enemy of America on the cinematic battlefield was a Communist Asian.

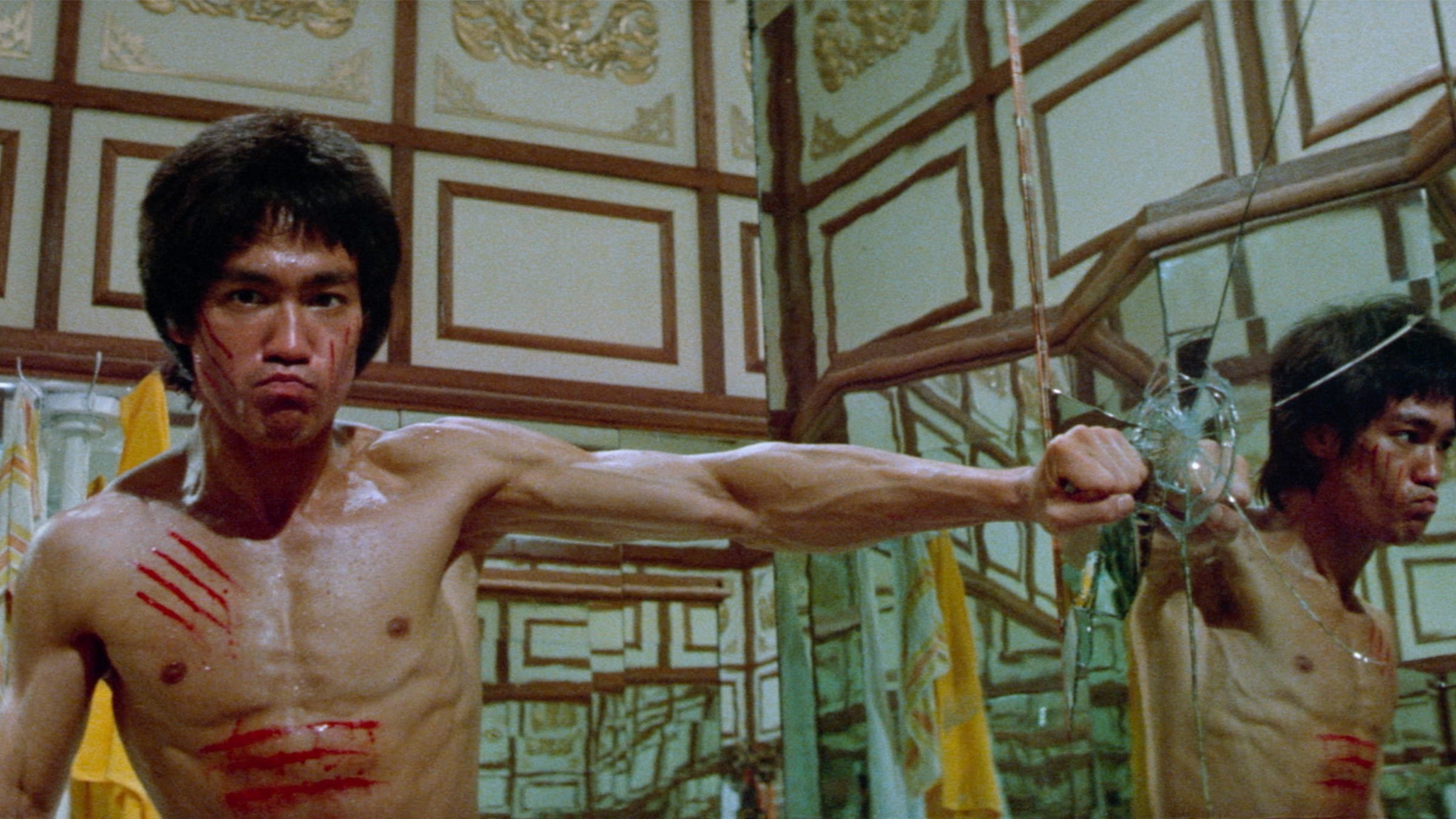

Bruce Lee in the climactic battle with the drug lord villain in Enter the Dragon.

By the time the United States officially entered the Vietnam War in 1964, the racial situation had only worsened. The age-old tradition of Caucasian actors in yellowface portraying Asian characters reached its nadir with Mickey Rooney cast as a Japanese landlord in Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961). Bruce Lee, who had been born in America to Chinese parents in 1940, was brought to Hong Kong as an infant. He returned to the States in 1958, after a career in film as a child actor, to finish high school and attend college in Seattle. It was there where he reportedly watched Breakfast at Tiffany’s with his future wife, Linda, and grimly realized that his ethnicity was hardly an asset in the Land of the Free.

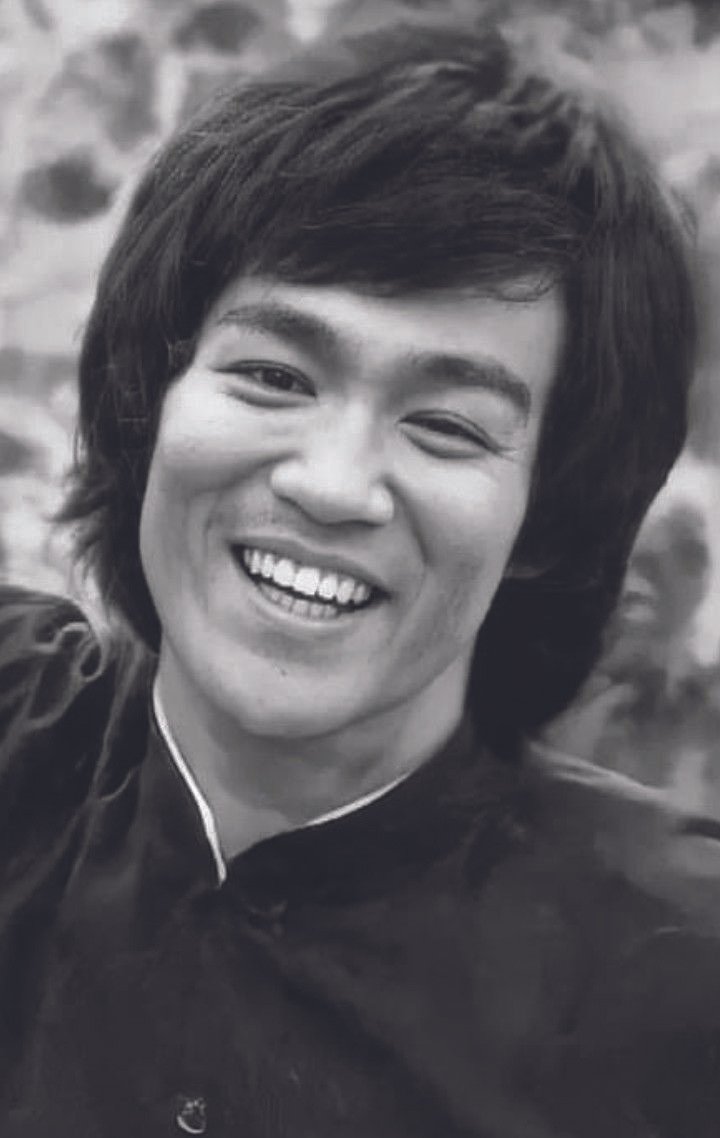

Bruce Lee in a more relaxed mood during a break in filming Enter the Dragon.

For Bruce Lee, fulfilling his dual ambition as a martial arts expert and a film star was an arduous journey. He gained local fame as a Chinese martial arts instructor and author, publishing Chinese Gung Fu: The Philosophical Art of Self-Defense in 1963. A string of spectacular martial arts exhibitions followed, eventually leading Bruce to Hollywood. Finally, in 1966, he landed the part of Kato, Green Hornet’s Asian sidekick, in the nationally syndicated superhero television series. He clashed with producers over the character’s “manservant” label, turning Kato into more of a partner instead. The Green Hornet was canceled after one season. A few guest appearances followed, but Lee felt that his career was stagnating. The final insult came when a television series similar to the one he had been developing under the title The Warrior went into production as Kung Fu. The Caucasian actor David Carradine was cast, in yellowface, as the now Chinese American hero. According to future Enter the Dragon producer Fred Weintraub, Bruce Lee auditioned for the part but was deemed “too authentic” by the series executive.

Reluctantly, Bruce Lee went back to Hong Kong. There, to his surprise, he learned that The Green Hornet was referred to as The Kato Show. As a preeminent representative of Chinese culture in Hollywood, Lee was predictably embraced in Hong Kong as a local hero. A top Hong Kong studio, Golden Harvest, immediately offered him a deal. The ensuing Big Boss (1971), Fist of Fury (1972), and The Way of the Dragon (1972) broke box-office records across Southeast Asia and turned Bruce Lee into a regional superstar. He was already in production on his next film, Game of Death (released in a nearly unrecognizable form in 1978), when American producers finally sensed a gold mine in the young action star…

To read the complete article, click here so that you may order either a subscription to begin with our Fall 2023 issue, or order a copy of this issue.

Jarek Kupść is a Polish American filmmaker, a lecturer in cinema at the Warsaw Film School in Poland, author of The History of Cinema for Beginners, and a contributor to Little White Lies, The Guardian, and The Observer.

Copyright © 2023 by Cineaste Magazine

Cineaste, Vol. XLVIII, No. 4