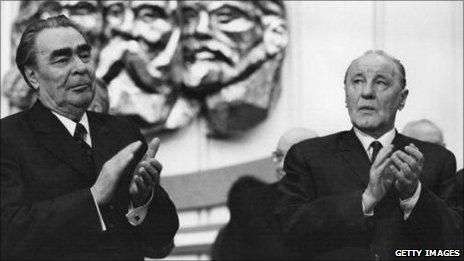

Hungary divided over Janos Kadar and his legacy

- Published

Hungary's last communist leader, Janos Kadar, is remembered fondly by some Hungarians and with loathing by others - which may be why his body was stolen from its grave three years ago.

The present-day chairman of Hungary's communist party, Gyula Thurmer, is effortlessly charming as he pours chilled mineral water, and settles down in his plush air-conditioned office to talk, in near-perfect English, about a controversial predecessor.

"Despite all the mistakes and problems," he says. "Everyone had work, everyone could learn, and all had opportunities. Janos Kadar is the symbol of this period."

Kadar (1912-1989) led the Communist Party and the country itself for 32 years, after the failed anti-Soviet Revolution of 1956.

He had originally supported the revolution, but turned coat after Soviet tanks rolled in. The "mistakes" to which Mr Thurmer referred include the reign of terror that Kadar presided over, in which more than 300 people were executed, hundreds more were deported to the Soviet Union, and around 13,000 were jailed.

'Goulash communism'

Here, however, is where the story gets complicated for some, and where the controversy surrounding Kadar and his era starts.

From 1962, the regime in Budapest started liberalising society and the economy, permitting (within strict guidelines) some freedom of speech and the freedom to trade on the open market.

Kadar also arranged substantial loans from the West, with the result that Hungarians enjoyed arguably the highest standard of living in the Eastern bloc.

The system was dubbed "Goulash communism", and Mr Thurmer says it deserves more praise than it generally receives.

"Goulash is a good thing - indeed, I often enjoy eating it myself!" he says.

"Communism is a decent system. Yes there were mistakes, and people ended up in jails, but we should not forget the positive aspects of this time.

"Millions were in work who would otherwise not have been. My father was from a poor background, and after World War II he was able to get a good job."

Bitterness

Whether or not Hungarians agree with this positive view of the party, few want to vote for it now that they have a choice - it has no seats in parliament.

The desecration of Kadar's grave three years ago, moreover, is a sign of the bitterness about the Kadar era harboured by some Hungarians.

Graffiti left at the scene said "Murderers and Traitors Shall Not Rest on Holy Ground 1956 - 2006".

"Kadar's grave is part of a section of the cemetery separate for great workers in history. Many think he has no place in such an area," says Dr Karoly Szerencses, a lecturer in History at Budapest's ELTE university.

"This is a very 'fancy' burial site. Several 1956 revolutionaries, however, were thrown into holes in the ground.

"Descendants of the 1956 revolutionaries find it unbearable for Kadar to be buried in such a way," he says.

Even in a graveyard, during the Communist era, some people were more equal than others.

The headstones of various key figures in the Communist Party are made of polished marble, with shiny lettering and the obligatory star at the top, while so many other tombstones seem to have been left to crumble.

'We cannot forget'

One man who cannot easily forget the Kadar era is Laszlo Ivan. Now the pensions spokesman for the centre-right Fidesz party (which in April swept to a landslide victory in Hungary's general election) the 77-year-old academic remembers the 1956 uprising only too well.

Professor Ivan showed me photos of a former university friend of his, Ilona Toth. The 24-year-old was executed in 1957 after a farcical show trial in which she was accused of the attempted murder of a policeman.

"The charges against her were ridiculous," he said, angrily. "Ilona was of the highest moral standards… She was hanged as a result of a false witness statement."

"The Communists still claim she was a killer," he says. "But there have been countless studies about Ilona's case showing her to be innocent."

"We cannot forget this phase of Kadar's life," says Professor Ivan. "Sure, he used his influence in the Soviet Union to make a more bearable society, but this period of retribution we cannot forget."

Debts and lies

There is, nonetheless, a sense that the country has yet fully to shake off its Communist legacy fully, thanks partly to the "good" side of Janos Kadar's policies.

"A direct economic effect [of the Kadar era] is a huge debt, and a lack of measures taken to solve economic problems," says Dr Szerencses.

Put simply, some Hungarians believe Kadar's other big crime was to persuade too many in the nation that they could have their cake and eat it - that they didn't need to worry about things like a huge foreign debt, augmented greatly by the generous pensions of the Communist era.

This in turn, goes the argument, has tempted many politicians in the country either to ignore its massive economic problems, or to lie about them.

This was brought to the fore most dramatically in the autumn of 2006, when full-scale riots broke out in Budapest after the then PM Ferenc Gyurcsany was caught on tape saying that he and his party had "lied, morning, noon, and night" about the national debt and other problems.

Reward

Peter Salas, a security expert at the Strategic Defence Institute, thinks the problem is deep-rooted in Hungarian society.

"Hungarians would, I think, like to have the best of both worlds: we want to receive money from the state, but we don't want to have to pay taxes," he says.

"This is the biggest problem. It is why our relationship to the past is many-faceted."

Kadar's skull and some bones are still missing three years after their disappearance, and the trail of the grave-robbers has gone cold.

It's not a priority for the Hungarian police, or the Hungarian media, Mr Talas speculates.

The state is willing to pay for results, however. A reward of two million forints (almost $9,000) is promised for information that identifies the culprits.