The man who can't feel pain

In The Curious Cases of Rutherford and Fry: A World of Pain, presenters Adam Rutherford and Hannah Fry meet a man with a rare genetic condition that means he doesn't feel pain at all.

Steve Pete went nine months before realising he'd fractured his back

Three years ago the 37-year-old from Kelso, Washington, experienced tingling in one of his limbs. “I started to have a weird sensation in my left arm,” says Steve. “It was kind of numb over by my shoulder blade.”

Months went by and eventually Steve decided to get it checked out by a doctor. “The specialist looked at my x-rays and asked, ‘have you been in a car wreck recently?”

Steve had three fractured vertebrae – an injury that could only have been caused by some form of extreme physical trauma – and yet it took Steve a year to work out what had happened: “I remembered that we were out in the snow… I went running down this hill with this inner tube and I jumped on to it and I did a scorpion where my legs went up over the back of my head. That’s probably what did it to me.”

Despite the severity of the potentially crippling injury, Steve felt nothing because he was born with a rare physical condition: congenital insensitivity to pain.

When Steve was a baby, doctors held a Bunsen burner by his skin until it blistered

Steve was just a baby when his parents noticed there was a serious problem. Going through the teething process, he had “chewed off a pretty significant portion” of his tongue. “That alerted my parents that something was definitely wrong with me.”

It was 1981 and genetic testing wasn’t available. So to test his pain receptors the doctors held a Bunsen burner close to his tiny foot, until Steve’s skin started to blister. But his parents were surprised when even this extreme event didn’t make their baby cry. When he was sent for further testing and showed no reaction to needles being run up and down his spine “they were fairly certain that what I had was congenital insensitivity to pain.” Steve was just six months old.

What is congenital insensitivity to pain?

In Radio 4’s The Anatomy of Pain: Knowing Pain, the neurologist Prof. David Bennett explains the cause of this very rare condition.

Each one of us is born with a group of sensory neurons that are designed to detect tissue injury, says Bennett, and “they’re only activated when there is some kind of stimulus.” That might be a burn, chemical damage or a mechanical injury like a broken back. In people suffering from congenital insensitivity to pain, those neural circuits don’t develop properly, and so they can’t feel pain in the same way as others.

“Historically these people didn’t really get to adolescence”

Pain researcher Professor Irene Tracey explains how sufferers of CIP were often enrolled as freaks at circus shows, performing all sorts of death defying stunts for money: “Of course what happened was they didn’t get that ‘good alarm’ body warning pain.” Unable to feel their injuries, and protect the damaged tissue, they would get infections: “First thing they knew they had a temperature, often sepsis and then death.”

Steve has broken around 80 bones in his body

Because those suffering from Steve’s condition don’t feel that acute pain, they often experience lots of fractures.

“Acute pain – this pain from a burning hot stove or putting your limb in an extreme position where you might break it – is incredibly important to avoid injury,” Prof. Bennett explains. “Because those suffering from Steve’s condition don’t feel that acute pain, they often experience lots of fractures, particularly when they’re toddlers and when they’re growing up.”

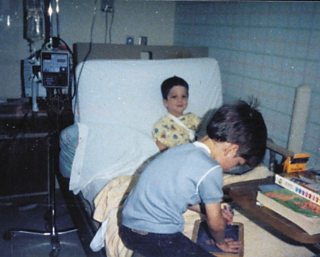

This was certainly the case for Steve. A lot of his childhood was spent in hospital, with his longest stay lasting 14 months. “The hospital staff there were very well acquainted with us,” he says.

Did his inability to feel pain make him more of a risk-taker?

“Definitely. As a child you don’t really care about the long-term effects of injuring yourself… You don’t think that far ahead.”

“Jumping on a bicycle and just taking off down a steep hill with no safety equipment on” or “trying to hit a wooden ramp” were risks that Steve would take readily as a child. He recalls how he would jump out of trees, or place mattresses on the ground and launch himself from the roof of their house. “Jumping off from high places is probably the most damage I’ve done to my body when it comes to broken bones.”

Steve had to establish a new “alarm system”

As Steve grew up he learned not to touch the stove and to always slice food away from himself –habits that most people pick up instinctively, but that he had to be taught.

In the absence of pain, Steve has also had to learn other pieces of evidence that reveal his body has been damaged. The last bone he broke was in his foot and he could tell something was wrong the next day because it was swollen and abnormally warm. He’d also been able to “feel tingling that wasn’t normal”. And although Steve can’t sense the pain of burning his skin, he can feel if something is dangerously hot and knows to move away from it.

“There’s quite a lot of downsides to not feeling pain”

For chronic sufferers, a life without pain might sound like heaven, but it has brought enormous amounts of suffering to Steve and his family.

“You don’t want to see your children in pain, but you also don’t want to see them injuring themselves and not knowing it.”

Although he doesn’t feel pain, Steve can sense uncomfortable pressure in his body, and the healing process can be very taxing: “It depletes my energy to where I’m just constantly fatigued,” he says.

He’s got a bad left knee, which he’s been dealing with since he was 16 years old, and it’s getting progressively worse: “I can’t walk for long distances like I used to.”

And then there’s the constant vigilance. “You just have to assess risks constantly, although over time that just becomes second nature. You kind of know what you should and shouldn’t do.”

Despite everything, Steve wouldn’t choose to feel pain

Steve’s brother Chris also suffered from the genetic condition and found it very difficult to live with. An outdoorsman, he enjoyed hunting and fishing – but doctors informed him that he had only a year before a back injury would leave him reliant on a wheelchair. “That, compounded with everything else, was just too much for him,” Steve explains. He took his own life ten years ago.

Thankfully, Steve’s daughters don’t suffer from the congenital condition – a source of immense relief for their dad. “You don’t want to see your children in pain, but you also don’t want to see them injuring themselves and not knowing it.”

Despite all of this, Steve says he wouldn’t choose to feel pain himself. “I’ve had so many injuries throughout my life, and I’ve got arthritis in my joints – I would just be in constant pain if I were to suddenly feel it,” he declares. “You couldn’t pay me enough to feel pain!”

You can hear more of Steve Pete’s interview in The Curious Cases of Rutherford and Fry – “A World of Pain.”

More from Radio 4

-

![]()

The Curious Cases of Rutherford and Fry

Science Sleuths investigate everyday mysteries.

-

![]()

Ten thing you've always wanted to know about yourself

Science has the answer.

-

![]()

Seven quirky documentaries to make boring journeys go faster

Featuring salamanders, cyborgs and pigeon whistles.

-

![]()

Eight tips for improving your sense of direction

Do you struggle getting from A to B?