The subject of a lifetime: Glenside artist Zenos Frudakis has been sculpting MLK since ’80s

Morning Edition host Jennifer Lynn speaks with a local artist about creating sculptures of Martin Luther King Jr. since the 1980s.

Listen 6:45

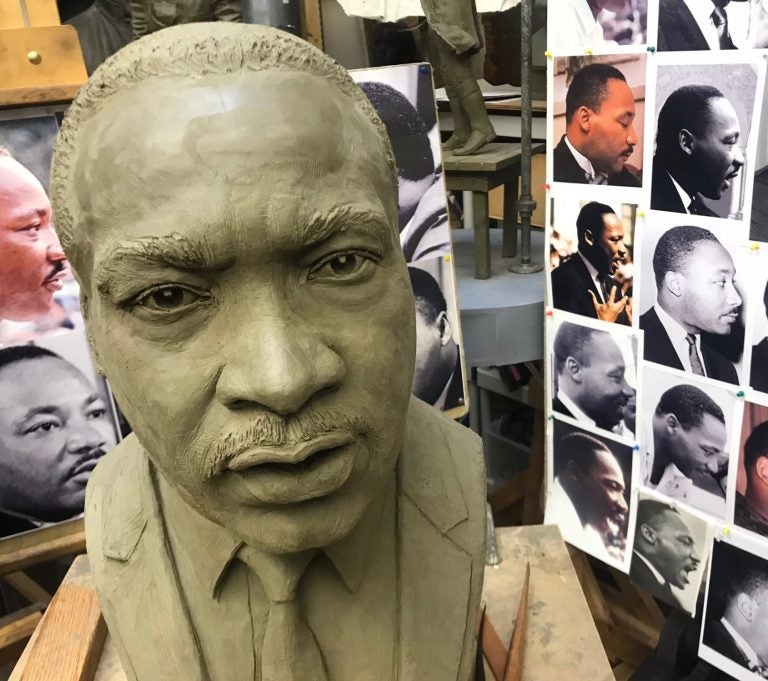

A sculpture of Martin Luther King Jr. by Zenos Frudakis is destined for a sculpture garden where it will join likenesses of Nelson Mandela and Mahatma Gandhi. (Scott Grote/WHYY)

On the 50th anniversary of Martin Luther King Jr.’s death, his voice still resonates. As for King’s image, it’s indelible — preserved in old photos, film, and sculpture.

Montgomery County artist Zenos Frudakis has had a hand in that. He’s been creating lifelike sculptures of King since the 1980s. They include one in Chester City, another in South Africa, and a new one destined for a sculpture garden at an unannounced location abroad. There, the likeness of King will hold court with those of Mahatma Gandhi and Nelson Mandela.

If you’re from the Philly area, you’ve probably seen Frudakis’ work. He created the Freedom Sculpture at 16th and Vine that shows the human form incrementally emerging from a wall. He’s pairing a miniature version of the sculpture with his newest rendition of King.

Morning Edition host Jennifer Lynn spoke with the artist about his latest study of King at Frudakis’ studio in Glendside.

–

Would you please look at this study [of King] that you’ve created and just tell me who he is?

You see all these photographs, and these are only some of them. There are many down there on the floor, and I set them up so I could almost have him standing here from this profile, looking at the right side of his face, moving around to the three-quarters, to the front of his face, and to the other profile on the left.

So we’re in like this panorama of photos of Martin Luther King right now.

It’s almost like wallpaper. It’s all the way around. But what I’m trying to get a sense of, him standing here next to me, which I would have if he were alive. And I would walk around him, and I would turn him so I could see him from all directions.

What I love about these pictures is he almost always looks like he’s about to speak or he is speaking. And then when I look at the sculpture study that you’ve made, I have the same feeling. You can see his eyebrows are pressed down, his eyes are wide open, he’s looking like he’s formulating a statement. Is that important to what this looks like?

It is, and you have to make decisions, constantly there are aesthetic decisions. You get to that road, and you decide, do I take this one to the left or do I take this one the right? And each road leads you to another road, and you get further to where you want to go with it. It’s kind of intuitive, but you can see in some of the pictures there is more of a frown. Some of them you don’t see it as much, some of the pictures are probably touched up, so you can’t trust that altogether. All the pictures are done with one eye. I’m working with two, and I’m aware of the distortion, there’s always a little distortion.

You have to make him three dimensional, you have to bring him back to life.

That’s what I’m trying to do. I’m trying to bring him back to life, though I know in some ways it’s futile. If I can bring him back to life, then maybe for some people who see him — especially where the sculpture is eventually going to go, and especially for people who didn’t know him, younger people — it gives them a sense of what he was like a little bit, I hope. If it has life, it gives them a sense of him as a living person.

There’s a tone to this sculpture, tell me about that.

Well, I’m trying to get a sense of intensity in his eyes, an intelligence. That history kind of found him in Montgomery, Alabama, with the bus boycott and everything, and he grew into the historical moment. If that hadn’t happened, I don’t know who he would have been. You get the sense of how a person can be at the right place at the right time, and it doesn’t just make him, he makes the history. And I wanted to get a sense of that. I wanted to get a sense of his eyes, they kind of go up at the ends a little bit. And he has these little ears. Do you see them?

I never really noticed his ears before.

And they pinch right there. When I look at this, it’s almost like me walking over a landscape. Even though there are words for some of this, you know the nasal bone and the maxillary and the zygomatic bone, and all of that — it’s not the words, it’s the shapes. It’s almost like you have to walk over this landscape. And I’ve walked it.

What is he saying?

Depending on who sees, he’ll say something differently to them. But for me, when I look at it, he’s talking about the struggle for freedom. He’s talking about a struggle for people who don’t have as much freedom as others because you can see the pathos in his face, but also see the strength. And you see some sensuality. I think there’s all of that in his face. There’s a kind of animation, there’s an intelligence, bright eyes, shiny black eyes. You can see those eyes are very, very bright.

How hard is it to do eyes?

Eyes are very difficult. You know we’re very judgmental of eyes because we look at each other in the eyes. And so, if that’s not right, people notice that right away usually.

What would he say?

What would he say? I would like to think that he would be pleased to be remembered, if not just for himself, not for an ego reason, but because of what he stood for and what he died for, what he lived for and what he died for.

I see a couple of pictures in this sort of surround-sound scape of photos everywhere on the walls here of Dr. Martin Luther King. There are maybe two where he actually has a slight look of levity on his face. I’ve never seen him portrayed like that in your work. Is that something you wish you could capture in him?

I’m probably too serious. As an artist, you project some of yourself, and when you sculpt someone, it’s part of you and part of them. There’s kind of an intersection between the two of you, and that’s where the art is. Whatever experience it is, you’re painting a landscape, a landscape is there, you’re here, and where you overlap, that’s the piece, that’s the painting, and that’s what these are. This is my impression, my my experience of him through my senses.

So this is King and you, this piece?

And everyone else who experiences it, brings themselves to it.

We spoke on the phone briefly before we set up this interview and you said working on King is one of the hardest things for you.

King has been the most difficult person I’ve ever had to sculpt. There’s a subtlety about his face. And maybe because you don’t have the great voice to go with it — and the presence that you see in video and in photographs, it’s very, very difficult. I think that after all the Kings I’ve made, I think this last one, this is my best. I finally feel like I’m getting to know him.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.