Blog Archives

Fungus Among Us

Fungi in the Forest

By Bruce Rottink, Volunteer Nature Guide and Retired Research Forester

The fungi (singular = fungus) at Tryon Creek State Natural Area (TCSNA) are endlessly interesting. They’re more than just the cute mushrooms along the side of the trail. They take on many forms, and have more diverse lifestyles and habitat preferences than we might imagine.

What do fungi look like?

When you say “fungus” most people think of either mushrooms, or that fuzzy stuff on the tomato you left on the counter too long. In truth, they can look like almost anything.

A hypha (plural = hyphae) is a single living “thread” of a fungus. Hyphae are the building blocks of every part of the fungus. Even mushrooms, the fruiting body of some fungi, are just a tightly packed bunch of hyphae. The fungus pictured below grew underneath the loose bark of a dead western redcedar (Thuja plicata) tree on the Big Fir Trail. The fuzzy white strands surrounding the solid central tan fungal mass are a good example of fungal hyphae.

Some fungi do something really different. The honey fungus (Armillaria mellea), for example, sometimes uses a huge number of hyphae to create a structure called a “rhizomorph”. Rhizomorph roughly means “root-like thing.” These rhizomorphs are essentially hollow tubes made up of many, many hyphae. They are typically 3 or 4 mm wide (about 1/8 of an inch). Rhizomorphs are created by the fungus to move water and nutrients from one place to another. It has been suggested that when the fungus starts running out of nutrients in one place, it uses the rhizomorph to “explore” for another good location, and then transports some nutrients to that location to jump start the next fungal infection. The rhizomorphs of the honey fungus are black and about the same dimensions as a shoelace. In fact, foresters refer to this species as “the shoelace fungus.” The rhizomorph frequently grows between the bark and the woody tissue of the tree. The photo below shows a log lying alongside Old Main Trail. Several rhizomorphs are clustered side-by-side to form the big black splotch in the middle. This rhizomorph became visible when the bark fell off the log.

What else might fungi look like?

One form of fungus that is common to the bigleaf maple (Acer macrophyllum), is powdery mildew that grows on the surface of the leaf. Mostly it just looks like a light coating of white fuzz or dust, but it is a fungus. Sometimes you may see black dots which are the spore-producing bodies of this fungus.

What do fungi like to eat?

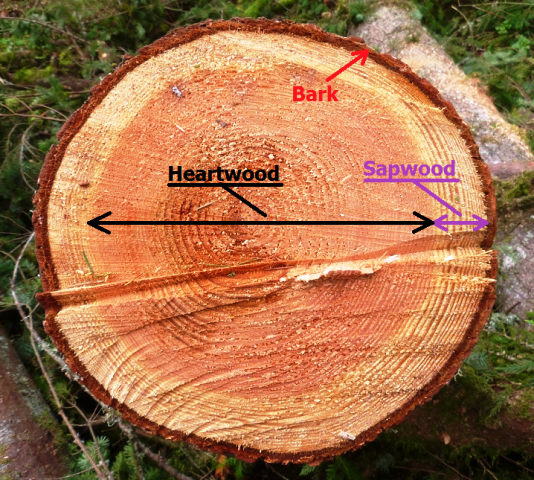

You might think that since fungi are mostly just “rotting stuff” that they would eat anything. However, certain fungi have definite food preferences. Take for example wood decaying fungi. In medium or larger woody plants, there are two distinct kinds of wood. In the cross-section of a Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) below you can see two different colors of wood. The peach-colored wood in the middle is the heartwood, while the pale wood around the edge is the sapwood.

For fungi, the heartwood and the sapwood are two different types of food.

Heartwood:

The bad news: It is loaded with chemicals (generically called “extractives”) which inhibit the growth of fungi. It contains very little easily digestible nutrients like stored starch.

The good news: There are no living cells to “fight back” against a fungal invasion.

Sapwood:

The bad news: There are lots of living cells which sometimes fight back against the fungi.

The good news: There are lots of easily digestible stored foods like starch and sugars.

As you might suspect, some fungi have evolved to favor the heartwood, and some fungi have evolved to favor the sapwood. One manifestation of these preferences was found on the end of a log at TCSNA on the ground near the Nature Center. The fungal fruiting bodies indicated by the red arrows are from a species growing in the sapwood. The fungal fruiting bodies indicated by the white arrows are of a species growing in the heartwood. The third fungus, indicated by the yellow arrow, is also growing in the sapwood. I have seen other examples of this kind of distribution, but this was the most dramatic. Please note that the lower part of the log is hidden by the dead leaves on the ground.

What parts of the wood are the fungi eating?

Not only do different fungi attack different parts of the tree, they also eat different chemicals in the wood. Wood is made up of two main chemicals. The first is cellulose, and the second is lignin. Cellulose is a simple molecule made up of a long chain of glucose (a type of sugar) molecules, and only glucose molecules. Each glucose molecule is bonded to the next glucose in the same way. Lignin, in comparison, is a very complex molecule. It is made up of a variety of molecules, which are linked together into a network, not a nice straight chain. In addition, the bonds between the molecules which make up lignin are extremely variable.

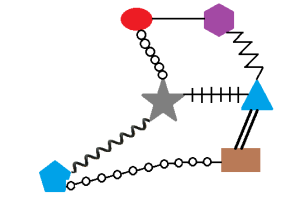

Fungi use enzymes to break down large molecules. Digestive enzymes usually have one very specific bond that they break. The bottom line is that cellulose is easier to digest than lignin. The diagrams below convey the idea of lignin being complex compared to simplicity of cellulose. The colored shapes are the component molecules of cellulose and lignin, and the black lines (or chains, or spirals) represent the diversity of bonds between those molecules.

In the real world, most wood appears to be light brown. Cellulose is pure white. Lignin is brown. So if a fungus eats all the lignin, the residue looks white. (Perversely, these fungi are called “white rot”, although the part of the wood they are eating is brown. Oh well!) My experience is that examples of white rot are less common than examples of brown rot. Pictured below is an example of white rot from a log near the Red Fox Trail.

The fibrous cellulose left behind by the fungus is chemically identical to cotton fibers. Just think, your next tee shirt could be made out of a tree!

The brown rot fungi that only eat cellulose, leave behind the lignin. This is quite common. A stump with the cellulose eaten out of it is pictured below.

After the wood is attacked by brown rot fungi, it tends to break into cubes. This leads to another name for this type of fungi, “brown cubical rot.” The lignin is not fibrous at all. This is seen in the picture below.

White rot, brown rot, heart rot, powdery mildew and more, the fungi of TCSNA are a diverse and interesting bunch. They play many important roles in our forest’s ecosystem. While their small size frequently makes them hard to find, keep your eyes peeled! The rains of fall have already started to bring out their fruiting bodies in all their glory.

Discover more about our Fantastic Fungi here!