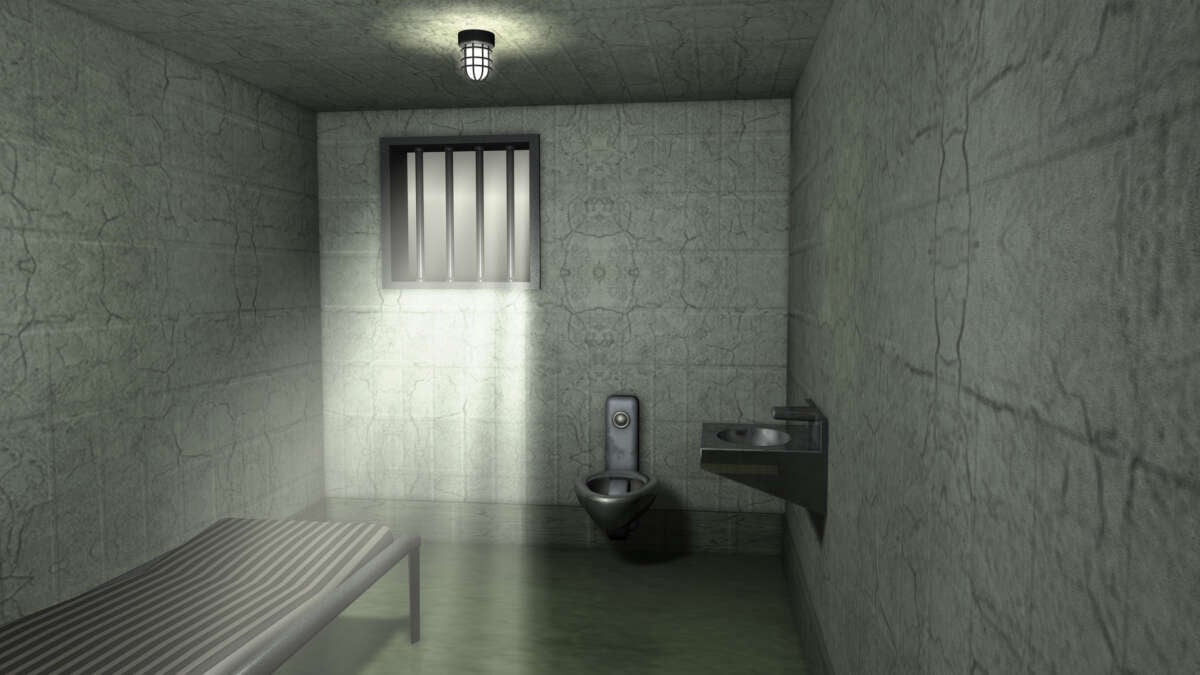

The morning quietly waits for the public address system to emit its familiar message. I am laying on my top bunk, eyes half-open, while an opaque light is streaming through a small, barred window, brightening the pale cinderblock walls, paint-chipped metal table, rusted basin and blue metal door of a room I’ve learned to call my home. In the amplified quiet, I can hear my cell-mate breathing as he sleeps on the bottom bunk. Thoughts of reflection and drowning images of a life long lived behind bars are fighting against my willingness to wake up.

Out of the many places on the planet, prison life is the least known to the United States public. The prison movies, scripted reality shows and prison documentaries (which tend to glorify violence, gang affiliation and a toughness persona) rarely denude the mental and emotional anguish a confined individual endures on a daily basis; rarely does the denigration of the prisoner’s dignity and self-worth take center stage to give us a clear picture of what confinement is really about.

Prisons are depressing places. They remind you of modern concentration camps. Their design and architecture somehow tend to hold a placid air of oppressiveness, swallowing all hopeful optimism. The perturbed loudness and human uneasiness — in tandem with the rigid rules and penal mechanisms enforced by the ruling captors mandating when to wake up, what to eat, when to take a shower, when to receive a visit, what books to read and even when to pray — are a constant reminder that you’re just a number without a name, without a life. And if you throw in the gangs (the Aryan Brotherhood, Mexican Mafia, Norteños, Black Guerrilla Family, Aztecas, Latin Kings, Nietas, Crips, Bloods, Gangster Disciples, Vice Lords and others), prisons generate tension and fear at gargantuan proportions.

I remember the first day I walked in through the non-revolving door of the U.S. penitentiary in Beaumont, Texas. The year was 1999. The picture of 40-foot granite walls topped with razor wire, enclosed steel fences upon fences, prison bars lining each window and eight gun towers overseeing the massive compound immediately told me about the encompassing, controlling measures of such a place.

The spotless, tiled floor inside the lobby — a wide, window-filled room, furnished with sofas, counter tables, plants and vases — appeared out of place as three prison guards led me in. I was shackled and fettered with an attached chain mid-waist, moving at a snail pace due to the ankle restrains biting into my flesh, as the guards demanded, “Step it up! We ain’t got all day.”

As we entered the last door leading inside the prison, a fearful feeling came over me followed by a shortness of breath. Something to do with the visibility of armed guards, prisoners in similar attire and steel and concrete all around.

I was led into a multi-purpose room. The guards rapidly unshackled me. They asked me to remove my jumpsuit. They asked me to show them my hands, the bottom of my feet, the inside of my mouth, the bottom of my scrotum and testicles, and to bend over and spread my cheeks so they could see up my anus to make sure I wasn’t carrying any contraband — although I had already been subjected to such a demeaning process three times over on the way to the big house.

In no time, I was photographed and fingerprinted, dressed in prison greys and thrown into the prison general population holding a blanket roll under the crook of my arm and a small bag filled with cheap soap, a toothbrush and toothpaste, and a prison guide booklet, ready to embark a never-ending journey of prison life.

The first few months in prison are the hardest. You have to stay on your toes due to the unexpected violence which can explode at any given moment over the pettiest things; ‘disrespect’ the prisoners and the gangs call it. You have to adapt to the few hours of visit from your family (if you have one willing to drive hundreds of miles to come see you) on the weekends. You have to learn to prioritize the 15-minute phone calls from a 500-minute monthly allowance. You have to learn to enjoy the few channels on television. You have to buy the overpriced food items in the prison commissary and eat the non-nutritive prison meals. You have to rely on bare-minimum health care. You have to forcefully use the limited exercise equipment out on the recreation yard; and of course, willingly submit to your captors telling you what do, when to do it and how to do it.

Despite these perpetual limitations, a lot of prisoners still find ways to overcome the drowning dilemma of everyday sameness. Some choose to work in the kitchen preparing the meals for the other prisoners. Some work in the recreation yard or in the chapel or other prison departments under the guidance and supervision of prison guards. Others work in the textile factory sewing military pants for pennies on the dollar. Others educate themselves through prison education programs, firmly believing education will enable them to stay out of prison once released. And still others, more than a few, wind up caving in to the punishing routine of prison life (sleeping and watching television) and are quick to tell you, “We are killing time,” when in reality, time is killing them.

And then there is the secret emotional turmoil the prisoner refuses to talk about. The emotional and mental anguish that pounds on him day and night like a hammer driving a nail into the depths of his soul; the tears he cries late at night in the darkness as he lays down on his metal bunk staring at the wall feeling shame, guilt and regret, thinking of a family he once knew, a life he once had; the immense longing he has for the affection of a woman, the laughter and joy of youngsters playing and all of those little things the world takes for granted (your own food, your own clothes, your own life choices).

Finding himself troubled by his inner tremors and the neglect of his human desires, more than one prisoner relies on his faith — the ever-sustaining comfort that he’s not yet dead, the transcending belief, paraphrased from Psalm 139:8, that, “If he ascends unto heaven, God is there. If he makes his bed in hell, God is there.”

For without such deflating mechanisms, the prisoner’s heart becomes hardened, his emotions deadened, driven by a dormant rage ever-ready to strike against his captors or fellow prisoners at the slightest provocation; against a society that has designed a penal system to eviscerate his self-esteem and self-worth under extreme psychological duress — depriving him of his freedom, family ties, desires and dreams, and an opportunity at redemption — as he makes penance for breaking man’s law.

Dawn has arrived. The public address system has made its familiar message, “Count is clear. All prisoners accounted for. Begin normal operations.”

“Morning,” I say to Donnie. “You slept alright?” My cell-mate is sitting up on the side of his bottom bunk, too sleepy to answer. Our cell door swings wide open. A prison guard asks if we’re still alive. His usual morning routine.

A half hour later, breakfast is called and we’re both fully awake, dressed and ready to start another humdrum day in the belly of the beast. After breakfast, Donnie heads to the textile factory to fulfill his eight-hour prison job. I start my own job in a warehouse-looking building, sweeping, mopping the floor, wiping down table surfaces and rails for the 8,760th time. After 25 years I’ve become an automaton conditioned by a regimentation of prison life… my world evermore.