Below you can find a selection of the short stories and poems we’ve translated within our collective that we haven’t published elsewhere. Some are from our early days as a student group, while others are more recent.

More of our work can be found in the Available Now and Journals pages.

Short Stories:

“Shipless” by Pelin Buzluk

“The Haunted House” by Nezihe Muhiddin

“Scrap Paper” by Yekta Kopan

“Estağfurullah Üstadım” by Aziz Nesin

“The Secret” by Murat Gülsoy

Poetry:

Selected poems by Gülten Akın from her collection Beni Sorarsan

“Shipless” by Pelin Buzluk

Pelin Buzluk (1984–) is a contemporary Turkish author from Ankara. Born in 1984, she is the youngest writer whose works we’ve translated to date, and her stories were already being published as early as 2002. This story, from her 2016 collection En Eski Yüz (“The Oldest Face”), is told from the perspective of two different narrators, and comes to an unexpected ending.

Seas don’t murder anyone

In fact, they don’t want anyone

– Arda Kemirgent

I can’t think of the sea without any ships. It stretches to the horizon, out of sight. I immediately place giant ships on it. My chest relaxes. Because I’m the one who drowns immediately, even in front of a picture of the sea without a ship. Flailing on the inside and eventually, of course, sinking. I’m the one whose hat gets blown away and dress gets soaked and heavy while looking at Repin’s painting, “What Freedom!” I’m the one who sinks to the bottom. The fear, the horror that makes the waters rise in my dreams, filling my lungs… Now all of it is here, wide awake. We’re on a rowboat.

They would say, “You will work until the job is done.” One time, it lasted over thirty hours. By then, I had started to hallucinate. A dark horse was wandering in the shipyard. I went after it. Hasan came after me and brought me back. He also saw it when I showed it to him, though. We tossed a ship out onto the sea once every three or four months. I was afraid if we kept up this pace, there would be no room left on the sea. The ships stretched out to the horizon. You couldn’t even see the sea. People were travelling by hopping from one deck to another. They didn’t even think of the water. In fact, in order to understand the sea, its surface should be utterly empty. Only foam. In order to understand the sea, you should forget about people. Only rowboats should be allowed. With their humble rocking. We’re on a rowboat now.

The songs that ring in the ears of those who set out in a rowboat are well-known. So that we can forget about the sea a bit. The sea turns into a landscape. Wine-coloured smoke surrounds us. We blend into the landscape. Landscape paintings are always the same and happy. Far from misfortune.

My father arranged the boat. He said, “Don’t draw attention to yourself.” They know you. He probably thinks we build rowboats in the shipyard. “Set out before dawn,” he said, as if setting out for fishing. I said, “Like sending a mermaid to her home.” My father said, “Send her away before she figures it out.” Before she figures it out… After all, it’s Hatice. How could she not figure it out? Our father thinks we’re blind and deaf. He picks his nose, farts in front of us. When asked how many people are in the household, he frowns for a moment to think.

I’d only ever seen water in a glass. We wouldn’t raise our eyes from the ground in the steppes. Before I was even used to the sky… The first time I saw the sea, I felt nauseous. Its ebb was pulling me, and then releasing me. It was not childlike like the blue on the maps. We’d only ever looked at it closely maybe once. After that, only my older brothers were made to learn about the sea. From our house, the sea is only visible when standing on a chair, as an ill-matched, dark-coloured patch below the sky. We would think to ourselves, “Let it stay far away.” Let it bubble away over there. Let it do anything but drown us. That’s why when my brother tied my hands, I began to tremble.

“First, learn how to swim,” my father said to me and Hasan. We learned how that week. We’d done everything he’d ordered us to do thus far. We did this right away, too. Out of shame, we’d go to the sea early in the morning. There would not be a single soul if we were to drown. Back at home on the satin duvets, we’d show the girls how we swam. Hatice would burst out laughing. My older sister would hide her smile with her kerchief, looking like my late mother. After a while, we befriended the fishermen. I wish we never left those boats. I wish we kept on fixing the nets clumsily. Settling with our share at the end of the day. Now in my rough palms are Hatice’s wrists, so thin that they could break. The fragile body of the rowboat on the sea.

I search his face to catch his eye. He doesn’t look at me. I open my mouth slightly, wheezing. He wipes my spit from his hand, the one gripping the rope. He holds my ankles and straightens my legs, which I had pulled under my body. He does so with no difficulty at all. It’s like I’m numb. He ties my feet tightly. “Brother,” I say. I can’t help trembling. The water is already welling up, rushing over my chest.

Last time, my father had said, “If she is going to study, the responsibility is yours.” We thought we would be providing her with an allowance. Hatice was very good at painting. One could go to school to study painting too, Hatice explained to us, and we to our father, with difficulty. He just didn’t get it. Why would she study something that wouldn’t earn her money. Hatice could be an art teacher. She would bring home some money. My father seemed reluctant, but when he heard about the money, he became excited about new financial opportunities, and he was convinced. But the responsibility was ours. We would give her an allowance. Taking turns, Hasan and I would buy her what she needed from the shops that smelled of paint. Hatice would hold a tiny list in her hand, rising on her toes in excitement.

He doesn’t turn his face toward me. I think he’s crying. Because I’m crying. If only I didn’t care about myself, my existence so much. Then maybe I could calm down. But I do care. I want to live, that’s the reason why I’m still alive. Maybe in a few minutes, I will face a shipless, rowboatless sea. I will blend into the sea. My fear will come to an end. First I will become a bubbly struggle, then an eternal silence. My hair will drift gently, my face will become sleepy in the water. I will be tickled by the fish nibbling at me. In the water, I will forget the sea.

Her fingers were stained with paint. They would still seem spotless to me. I remember the day she was born. You can’t see people as fully grown when you’ve seen them as babies. There was the memory of that baby in Hatice. She had misbehaved and made a mess of herself. And together, Hasan and I were spoiling her.

I can’t help thinking of the moment he will toss me out into the water. If he unties me and pulls me to the shore now, I will think of that moment for the rest of my life. Night after night, when I’m about to fall asleep, I will step into unknown waters. He lights a cigarette. His hand is smeared with tar. The type they say will not wash off. I would scrub his hands with paint thinner on the days he met with his girlfriend. His hair is spotlessly clean, with lines from the comb still visible. He looks as if he’s ready to go to work. I see his eyelashes from the side. His eyes are blinking rapidly. His eyelashes extend to the inner corner of his eyes. Thick and long. I still can’t find his eyes. Maybe he’ll throw me into the water soon. Yet I still find him beautiful. I love my older brother. The more he keeps quiet, the more imminent my death becomes. I feel like I’m going to pass out again. I hope I pass out. I’m weeping and wheezing. My trembling doesn’t stop. I’m suddenly afraid that he will gag my mouth.

The poor little thing is so afraid… What if I say I couldn’t… Then my dad will send her with Hasan. What if I say I threw her into the sea? What if he’s hiding on the shore and watching? Is this fear not enough? What if I toss her out at once? I’ve already waited too long. Even if we go back, she’ll carry the burden of this memory.

I look at the sea. For this is my last look from the outside. The sea wells up, overwhelming my eyes like the first time I saw it. Shimmering and shining… it’s burning. The sun has already risen quite high. Seabirds are flying over our heads. Looking for fish, looking for people. I turn around and look at my brother. This time, I catch his eye. As if I have one last chance. As if I have one last thing to say in this scene. That’s why the curtain isn’t coming down. “Brother,” I say, trembling. “At least talk to people about me. Show my paintings, tell them about me.” I speak, but how much of what I say can be understood through my wheezing… I turn my head away. I wait for his final sentence. I wait with all my body, with every bit of me alive for the last time.

I didn’t gag her mouth. Why bother… She can’t even speak. Once she touches the water, I’ll pull her out immediately. And in the evening, I’ll convince my damn father. I lift Hatice up. I raise my head toward the sky. I’m a brother lifting his wounded sibling and crying out toward the sky in a bombarded square.

The moment she touched the sea, the rope around her ankles became untied. Her shirt slipped off her back, her brassiere fell apart, and her breasts appeared. Her legs conjoined and became scaled. The scales quickly went up to her waist. Her secret was revealed, like that of Camsap1 as she touched the water. She turned around and looked at me one last time before diving deep into the water. I couldn’t move, I was petrified. I stood aghast with my hands open as if in prayer.

Hatice! With a slap of her tail, off she went… But that girl had lived in our home! A mermaid, as fishermen would call it… Now, I’ll go and tell my father. I couldn’t kill her, because she found a way to live. Let’s let her live, father. Let all of us be freed from this death. Our Hatice turned out to be a mermaid. She blended into the sea and disappeared. Yet my father will meet me with his typical reaction: “That bitch!”

1 Camsap is a character in Turkish author Murathan Mungan’s 1986 collection Cenk Hikayeleri (Valor: Stories), which is a collection of legends and mythical stories. He appears in the story “Shahmaran’s Legs,” where he reveals the secret that he has seen Shahmaran, a mythical half‐human, half‐snake figure that commonly appears in the folklore of Turkey’s southeastern provinces.

“The Haunted House” by Nezihe Muhiddin

Nezihe Muhiddin (1898-1958) was an Ottoman-Turkish journalist, writer, and women’s rights activist who fought for women’s political rights and advocated for the removal of legal codes implementing Islamic divorce and polygamy. She was the chief editor of the weekly magazine Kadın Yolu (Woman’s Path, 1924-1927), and was a remarkably prolific writer, with approximately 20 novels and 300 short stories, along with numerous plays, scenarios, and operettas, to her name.

It was forty years ago. Agop the pastırma seller from Kayseri had hired an apprentice, also from Kayseri, for his shop at the Istanbul Fish Bazaar. Having served his master for a total of eight years, it was time for the apprentice Istimat1 to return home.

Master Agop gave his apprentice twenty gold coins that were sitting in his drawer. “May God grant you a safe journey! May you spend the coins in good health,” he said as he bid him farewell.

Having kissed his master’s hand and received his blessing, Istimat set out on his way. He was hoping to open his own pastırma shop when he returned to Kayseri with the twenty gold coins he received in exchange for eight years of service and, for eight years now, he had been living with this dream.

But things didn’t turn out as he had hoped. The day Istimat set foot in Kayseri, he was married off to a young, beautiful girl named Angelika.

It dawned on him when over half of the money he’d saved in Istanbul had been spent on their wedding. By the time everything had settled, the rest was gone.

Istimat looked for a suitable job wherever he could, but all his efforts came to nothing. When poverty knocked on his door, he started longing for Istanbul. Should his old master take him back, he wouldn’t spend another day in Kayseri. His wife, Angelika, was a smart woman, and was also concerned that they were running out of money. Finally, she told her husband:

“Do not worry about us… If you find a job in Istanbul again, go without delay!” she encouraged him.

But where could Istimat go, leaving Angelika behind? His wife was three months pregnant. He felt terrified whenever he remembered that he would become a father in six months.

One day Angelika said:

“Istimat, it can’t go on like this. I suggest you write a letter to your master in Istanbul! Let him know that you will be there soon! Make it understood that we cannot make a living in Kayseri!”

Feeling desperate, Istimat followed his wife’s advice. He wrote a touching letter to Agop the pastırma seller at the Fish Bazaar in Istanbul, saying that he would come work for him since he couldn’t get a stable job in Kayseri.

Agop’s response arrived a week later. Istimat’s old master kindly informed him that he could return to Istanbul within five or ten days, but if he delayed much longer, he would not be able to wait for him and would hire someone else.

Just as Istimat was preparing for his trip, his wife got sick. Since he could not leave her alone, he set out a few days late.

When he arrived in Istanbul, it was too late; Agop had got himself a new apprentice some time earlier. Agop even lightly reproached his old apprentice:

“I made it clear in my letter that if you are coming, you must come quickly. You were supposed to hurry!”

This hope of Istimat’s too came to nothing, but fortunately, his master Agop was a merciful man. He made it up to Istimat by giving him five gold coins.

“This should be enough for you to get started. In the evenings when you return from work, you may sleep in the small room above the store with our helpers.” He said.

Istimat bought a small portable stand for himself with the five gold coins his master gave him. With a few kilograms of lakerda fish on his stand, Istimat started making his way around the bazaar. Since his stand was spotless and his lakerda was of good quality, he found many customers in no time.

But his profits were barely enough to make a living, and he could not support his pregnant wife back in his hometown. As Istimat was mulling over how to make this work with his limited earnings, he received a letter from Kayseri signed by his wife Angelika. After announcing the arrival of their baby boy, she wrote that they were on their way, and would arrive in Istanbul in one week.

Istimat felt his blood run cold with dread. He could barely feed himself in Istanbul, and now his wife and son would be an additional burden. Where could he provide shelter for all three of them?

He was so worried that he could not sleep.

Finally, his wife Angelika showed up one day with Vasili, their month and a half old son.

Istimat rushed to his old master Agop:

“So here’s what’s going on…” he explained, and asked for help.

Master Agop was annoyed.

“You cannot sleep in the room upstairs anymore! You must look for another room!” he said.

Istimat agreed with his master. After all, he could not bring his wife among all those single men.

“I am at your mercy, master… tell me what I should do”

Knowing that this was all about money, Master Agop reluctantly gave him five more gold coins.

“Take this money… Go wherever you can! And leave me alone, for God’s sake!” he said.

Istimat left his master’s side with his head hanging down. With the last five coins he had received, he bought several more pieces of lakerda. He spent the rest on rent for a single room. This was how he got by with his wife and child for a while.

Istimat, half-hungry and half-full, could not improve his prospects with the money he made.

It was right about this time that in Elmaruf, the neighbourhood between Istanbul’s Vefa and Süleymaniye districts, Şahinde Hanim – the beloved wife of Haci Muhsin Bey, who was rumoured to have assets worth a couple hundred thousand liras – died.

Haci Muhsin Bey was completely enamoured with his wife. This unexpected death drove him mad. The poor man stopped eating and drinking for months, and melted away like a candle:

“Oh… Şahinde!” he would say as tears flooded from his eyes.

His wife had never hurt him. It had only been a year since they were married. During this one year, they hadn’t had the slightest disagreement. Whenever Muhsin Bey thought about the good days with his wife, he felt like his brain would jump out of his skull. He had stopped coming home since the funeral. He would walk the streets, sometimes beating his chest, bitterly remembering his Şahinde. There was no doubt that Muhsin Bey was madly in love. Doctors and clergymen kept trying to cure him of this horrible illness, but it was to no avail. Muhsin Bey had let himself go.

One day, Muhsin Bey hurried out of his house yet again, and wandered all the way to Hocapaşa. He was about to turn into a narrow street, when… didn’t he see his wife in one of the windows? There was no doubt that it was his wife. His eyes widened in amazement as he stayed stuck in front of the window. He could not take a single step forward or back. Every so often he would come to his senses and remember that his wife was dead, but every time he looked at the woman sitting by the window, he would mutter to himself:

“No… No… she is not dead… There she is, right in front of me! If she were dead, what would she be doing here?”

Muhsin Bey went to the shop at the end of the street and, pointing with his finger, asked the clerk, “Whose house is this?”

“Are you asking about the haunted house?”

“Is the house haunted?”

“That’s what they say!… But there are no spirits or anything like that inside, it’s completely empty. Only Istimat and his pretty wife live in that small room.”

Muhsin Bey immediately rushed back home. Describing the house where he saw the woman by the window, he told his head housekeeper:

“You are to rent a house in that neighbourhood right away,” he ordered. “Ask around and find out who the woman I saw is.’’ The housekeeper disguised herself as an elderly seamstress, put on her veil, and dashed out of the house, taking two maids along with her.

What a coincidence it was that the adjacent house had been vacated two days earlier. The housekeeper rented the house without any bargaining, took the keys, and went back to the mansion. Muhsin Bey was waiting, with his prayer beads in his hand.

When he heard that the house had been rented, he immediately ordered:

“Send the girls to the house today. As soon as they settle in, they should find a way to meet the woman. Who is she? If she is married, who is the husband? What does the husband do? The girls should learn these things thoroughly.”

Packing a few household items, the housekeeper and three maids moved to the house in Hocapaşa. While shopping at Andon’s store on the corner, they found out who she was by asking Andon. The grocer was a chatty man, and explained when the housekeeper asked:

“They too have just moved in. The woman’s name is Angelika. Her husband, Istimat, is a pastirma vendor. They also have a newborn. It’s clear that they are poor… They only buy bread from me. They’ve amassed quite a bit of debt.

The housekeeper was pleased with this report. She and the maids started watching the woman closely through the window. The husband would leave early in the morning, leaving Angelika at home with the child. Pastirmaci Istimat had a bad habit. He would lock her in and then leave the keys with Andon. He didn’t feel threatened by Andon because he was sixty-five years old.

The housekeeper would sit by the window pretending to sew, all the while keeping her eyes on the beautiful Angelika. Slowly but surely, a connection was being forged among the women. They would greet each other every morning. After a while, they started exchanging pleasantries from their windows.

One day, Angelika saw the housekeeper putting on her veil.

“Oh, my dear, said Angelika, “it must be so nice to go out. I’m locked in the house like this all day.”

The housekeeper, taking advantage of the situation, asked:

“Would you like to join us?”

Angelika sighed from afar.

“Even if I wanted to, I couldn’t. I’m a prisoner in the room.”

“It’s no big deal. If you want to come with us, we’ll get the key from Andon and open the door for you. Once you’re out, we can lock the door again and return it to the shop.”

Angelika mulled it over. The housekeeper kept prodding her.

“Don’t worry about your husband. We’ll be back before he returns.”

“What about the child?”

“Don’t worry about the child either. Give him a soother. He’ll be fine well into the evening.”

She couldn’t resist the invitation, for she had been yearning to be out in the sun for months. She had every right to see a bit of the world while she was still young. Who knows where her husband wandered off to from morning to night?

Ending on this thought, she made up her mind:

“Alright, my dear. As you wish. Just make sure my husband doesn’t find out.”

“Leave that to us.”

While Angelika was getting ready, the housekeeper went downstairs to get the key from Andon. When the Karamanli2 shopkeeper seemed hesitant, the housekeeper pressed two coins into his palm:

“Take these for now. You will get hundreds of them from the master in the future,” promised the housekeeper. Andon’s face lit up immediately.

“As you wish, my lady. Don’t you worry… Even if Istimat shows up, I’ll handle it.”

Opening Angelika’s door, the housekeeper said, “Come on girl, let’s go.” Following the housekeeper, Angelika went outside. They left the key with Andon, reminding him to look after the child sleeping upstairs and to make sure no one noticed.

The housekeeper, with the beautiful Angelika and the two maids, arrived in Sirkeci. From there, they jumped into a car and set out on their journey.

Angelika, who had never seen Istanbul before, was looking around, fascinated by all the streets.

“Oh my lady… what is this place?” she kept asking.

Passing through Beyazit, the car headed towards Süleymaniye.

Angelika, clapping her hands and delighted as a child, kept saying, “My dear, this is so refreshing. If it were up to Istimat, he wouldn’t even show me Istanbul in my dreams.”

Finally the car stopped in front of an enormous mansion. The housekeeper, helping Angelika out of the car, lied, “We’ve arrived at our friend’s house. Let’s have a cup of coffee and rest a bit. And then we will head back.”

They went inside. A large, fully-furnished anteroom… Magnificent sitting rooms with ceilings inlaid with mother-of-pearl… Gilded palace furnishings everywhere… Chambermaids in brocade dresses, with necks ringed in gold like pheasants…

Angelika was so astounded by this scene that she didn’t even notice where she was stepping. A little while later, coffee was served in cups with golden cup holders on silver trays. Angelika relished the fragrant coffee imported from Yemen. And the raspberry şerbet that followed was unlike anything she had ever drunk in her life. Following the şerbet came a crystal platter laden with oranges, bananas, apricots, almonds, and other such treats.

While Angelika was peeling an orange, Muhsin Bey slowly entered the room. Seeing an unfamiliar man, the beautiful Angelika shrieked. Muhsin Bey, trembling with excitement, said:

“Do not be afraid, my lady.”

And then, looking into the woman’s eyes, he added:

“Wouldn’t you like to be the lady of this mansion? Everything I own would be yours. Fifty servants would be at your service, you wouldn’t have to wear your clothes more than once, you wouldn’t have to eat the same dish twice.”

Angelika didn’t know what to say, how to respond. Muhsin Bey was not yet forty, and was quite handsome, too.

The Rum3 girl from Kayseri didn’t have the courage to turn down the fortune that fate had granted her.

Muhsin Bey spoke a few final words to Angelika:

“You are the spitting image of my deceased wife. It’s as if God created you as a pair. When I saw you in the window, I thought the dead had been revived! This is why I’m drawn to you. However, I will not force you. If you don’t want to, you may go back to your husband. I’ll give you an hour… Think about it, mull it over… Then give me your answer.”

Once he finished, he left the room, leaving the woman alone. The housekeeper spoke with Angelika, and succeeded in captivating her heart. She told her that she wouldn’t be able to find such comforts in her husband’s house, and emphasized that Muhsin Bey was a truly wealthy man.

When Muhsin Bey came back, he received Angelika’s answer: “I accept. I will stay here.” He felt as if the entire world were his.

That evening, Istimat the pastırma seller returned home exhausted without having sold a single kilo. He entered Andon’s store to pick up the keys. Andon greeted him with a smile, saying:

“Come in, Istimat Efendi!. Did your right eye twitch today?”

Istimat didn’t understand what Andon meant.

“What do you mean, Master Andon?”

“What do you mean, ‘what?’ It’s a godsend!”

Andon handed Istimat a red pouch. “Open it and count what’s inside. There are exactly twenty-five gold liras!”

Without opening the pouch, Istimat asked, “Who sent this?”

“I dont know who sent this either, because the man who brought it did not say anything, he just said, ‘Give this to Istimat Efendi,’ and he left.”

As Istimat gladly tucked the money into his shirt, Andon added, as if he had just remembered, “By the way, your wife left early in the morning and has not returned.”

Istimat sensed that there was a connection between the bag of money and the disappearance of his wife.

Baffled, Istimat asked, “How can this be, Master Andon? Wasn’t the key with you?”

“It was with me, but the ladies next door dropped by, saying they would take her out for a drive and bring her back home before evening… And just like that, they were gone. Neither the ladies nor your Angelika have come back.

Istimat was about to say a few harsh words to Andon when the clinking of the coins in the bag at his chest stopped the words in his throat. After all, it was twenty-five gold coins! Istimat would have to work another eight years to make that much money!

As Istimat turned to leave with the key, Andon called out to him,

“The man who brought the money said, ‘Tell Istimat Efendi that every month, we will have 10 gold coins for him!”

Istimat, who couldn’t decide whether he should be happy or upset about the situation, went upstairs to his room, opened the door, and saw his son sleeping peacefully on the ground with a soother in his mouth. Father and son spent that evening curled up together. When the morning came, Istimat went out with the baby to go look for a wet nurse. They found him a lady with an abundance of milk for three lira per month. With the rest of the money, he rented a small shop in the Fish Bazaar, where he began selling meze dishes.

Three days before the start of the month, ten more gold coins were left at Andon’s by the same unknown hand. This was how, every month, Istimat grew his fortune by ten liras and expanded his business, which continued to grow. But he couldn’t forget his wife, either. But not out of love. He was just wondering where she was.

One day, he had errands to run in Süleymaniye. As he passed in front of a mansion, someone called out his name.

“Istimat Efendi… Istimat Efendi…”

“Yes…”

“We need four kilograms of your best pastırma…”

Istimat was taken aback. How could the people in this house know he was a pastirma seller?

The next day, as he was delivering the pastırma, the door opened slightly.

“Take this, Istimat Efendi. Money for the pastırma.”

And what did he see when he opened the bag on his way home, but twenty-five gold coins…

At that, he understood that his wife was living in that mansion. Every time he passed by that mansion, which was quite often, he would hand over a few slices of pastirma, receiving a bag of gold coins in return.

Once she settled into Muhsin Bey’s mansion, Angelika began to loathe her previous life. After a short while, she was drawn to Islam and converted. She changed her name to Emine Hanim.

Emine Hanim hadn’t forgotten the husband and son she had betrayed. She thought about helping them when she saw them the very first time and she secretly helped them whenever she could.

This continued for years. He became as rich as Croesus. He bought one of the biggest grocery stores in Beyoğlu and began managing it. Istimat Efendi is alive even today, and is one of the richest men in Istanbul.

From time to time, some nosy people would ask teasingly:

“Istimat Efendi! You became rich almost overnight… Not that I’m jealous or anything. Your story seems to have a woman’s touch.” Sighing, he would answer:

“Is there anything without a woman’s touch?”

He was terrified that he would run into someone who knew the real story. Thank God that Muhsin Bey and his wife Emine Hanim were not the kind of people who would give away secrets.

There was only Master Andon who knew the truth. And he had left this world a few years earlier.

Muhsin Bey became very happy with his wife, and they had several children together. Anyone who saw them would swear that they led contented lives. And they lived happily ever after…

1 The original Greek spelling of this name is Stamatis.

2 The Karamanli were a Greek Orthodox minority group in the Ottoman Empire. Although they were ethnic Greeks, they were Turkish speakers, and used the Greek alphabet to write in Turkish.

3 “Rum” is a primarily historical term that referred to Greeks living in the Ottoman Empire. Today, this term would only be used to refer to those Greeks still living in Turkey, not including those in former Ottoman lands.

“Scrap Paper” by Yekta Kopan

Yekta Kopan (1968–) is mainly known in Turkey as a voice actor and television presenter, although he has also published poetry, short stories, and children’s literature. His TV work is generally on culture-related topics such as cinema and art, while his voice acting credits include popular movies like “Ice Age.” Although his fame comes primarily from these avenues, his written work has also received praise – his 2009 short story collection Bir de Baktım Yoksun won the Yunus Nadi Award and the Haldun Taner Award.

“This pen never leaks ink. Look how I’m shaking it. I’m opening the cap. See? Not a drop. But you shouldn’t use any ink other than its own brand. The other day a customer returned one of these. Guess why? He said it was leaking. Did you fill it up? I did. With what? With a brand I don’t know. What did I tell you? Only with its own brand’s ink. If you use a random brand, of course it will leak. Do you know what it’s like? Let’s say you could only eat dishes prepared with sunflower oil. What if I made you eat something with corn oil? Your stomach would get upset. If it’s too sensitive, you might even have, well, you know. I mean, people should take care of their pens as they would themselves. But they just don’t get it.”

He shakes the pen as if he’s trying to poke it into the customer’s eye. The man gets annoyed by this aggressive gesture. He looks around. Suddenly, the snap-fastened pocket on the chest of his coat catches his eye. It was open. He tries to snap it shut. His nipple hurts as he presses on the flap of the pocket. He changes his mind about buying the pen. The salesman stops speaking. The few seconds of silence grow on the white walls of the shop; time disappears.

Someone must speak. They both know that such a silence is not innocent. The salesman, who parts his blond hair in the middle at least twenty times a day with the plastic comb from his left rear pocket, makes a final attempt: “Would you like me to show you a different model?”

The customer shakes his head in silence.

Two men. One of them has a fancy pen in his hand, the other looks pensive. They turn their eyes towards the stack of scrap paper sitting on the counter. They look at the scribbles left by the previous customer. There’s a name among the random lines, barely visible. A woman’s name. For a moment, they both imagine that woman.

The man turns his back without saying a word. As he leaves, he nearly bumps into a woman entering the shop. At the last moment, he catches the salesman crumpling and throwing away the topmost piece of paper.

A warm flow of ink fills his heart.

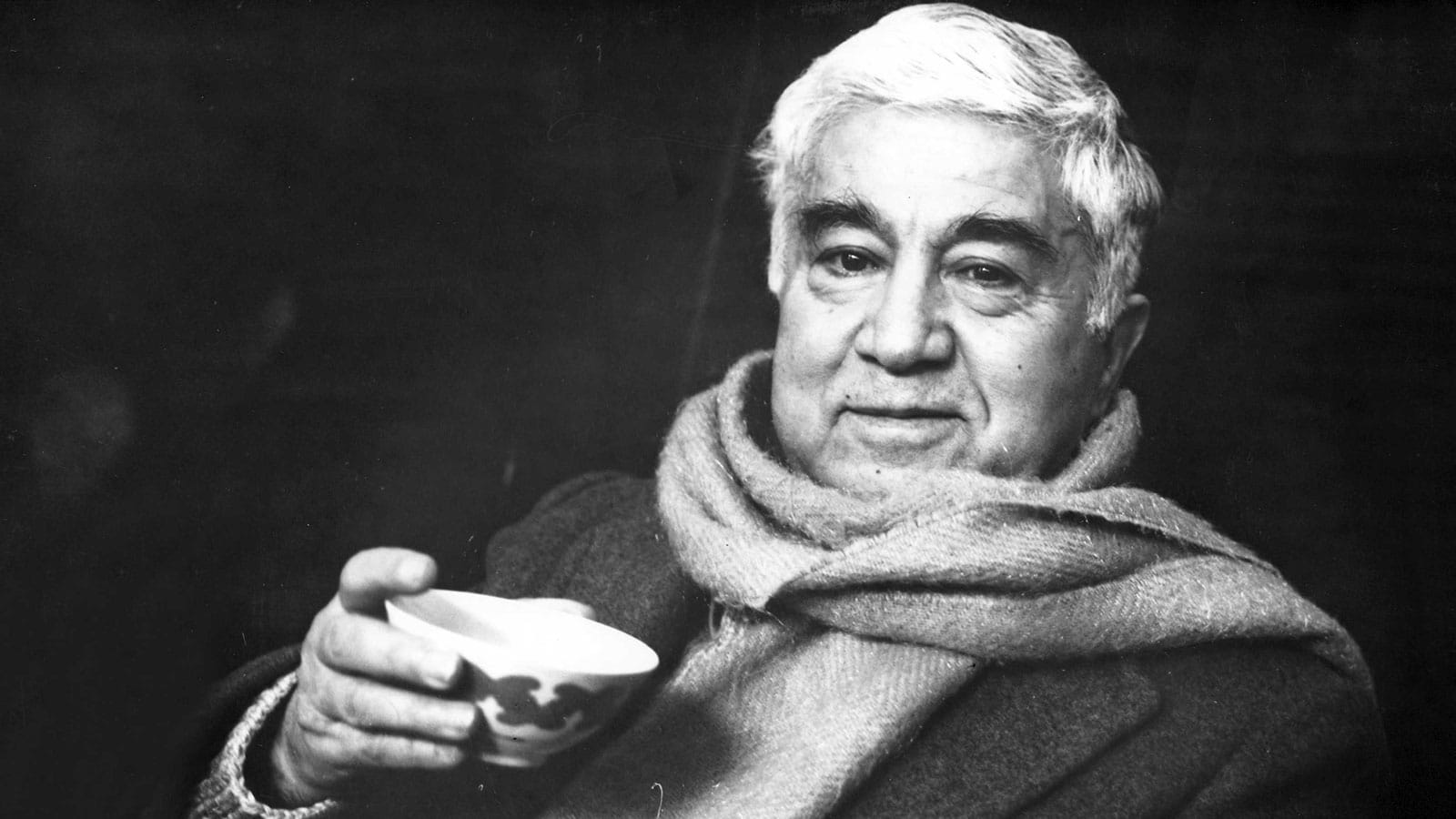

“Estağfurullah Üstadım” by Aziz Nesin

Aziz Nesin (1915-1995) was a popular and influential writer, particularly known for his satire. He was also an activist, and a leader who united creative intellectuals across the country in their criticism of the 1980 coup in Turkey. He was also critical of religion and spent the last years of his life confronting religious fundamentalism, which brought him into conflict with Islamic organizations. This tension was exacerbated by his translation of Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses into Turkish, which outraged those who believed it to be a blasphemous text. While he was attending a predominantly Alevi festival in Sivas in 1993, a mob set siege to the hotel where he and other attendees were staying, and set it on fire. Although most guests – including Nesin – managed to escape, 37 people were killed, including several prominent Alevi cultural figures.

Note: The two words in the title are repeated often throughout the story and are important to its plot, so we’ve opted to keep them as they are. Estağfurullah is an expression of politeness that is the equivalent of saying “You are most welcome” or “Not at all!” in English. Üstad is an honorific used to convey respect for someone due to their expertise and maturity, and together with the -ım suffix, can be translated as “my master.”

The renowned author was sixty-five years old, but, since famous people are often thought to be older than they are, his readers also believed he was much older. You know, as if he were living for no reason, leading a pointless life. The fact that he became famous at a young age also contributed to this illusion.

Famous authors are thought to be not only older than they are, but also richer. With such fame, how could one be without money! Who knows how beautiful his house is, how valuable his things are, his house must be full of antiques.

The public wasn’t being unfair in believing that the author in question was older than he was. Because like all those who live fast, he had aged poorly and looked tired. They weren’t wrong to think that he was rich either. His wardrobe wasn’t full, but his five pairs of suits – the newest of which was ten years old – still looked brand new, and since he had a sense of style, he exuded wealth. Even though he had only ten lira in his pocket, he generously and easily spent them as if he had ten thousand more. That alone was enough to make him look rich. In fact, for a long time now, he had been having trouble making ends meet. He was at a stage in his life where his fame wasn’t earning him money anymore. What was it? Maybe his time had passed? No one asked him for any magazine or newspaper articles anymore. And it had been a long time since the publishers had requested a novel from him. What could a person do at this age, who had done nothing other than writing, and who had lived by the pen for such a long time? He thought his star would always be bright. Had his star really faded away? These days people still knew his name, they whispered his name to each other as he passed by on the street, through the crowds, or on public transit.

He had worked in the newspapers for many years. But now, no one from his generation was in a management position at any newspaper anymore. If he had some old friends working at the papers, he would go ask them for a job. He didn’t know the staff or the editors working there now. Yet they knew the famous author, since wherever they saw him they greeted him with respect and used the honorific üstad.

Regardless, he had to visit the newspapers and remind them of who he was. It wasn’t wise to have let himself fall so far away from the publishing circles. If he were around, maybe they would remember him, and someone would request an article, a translation, or a serial from him.

That morning, he dressed more carefully than usual. First, he visited the newspaper with which he had had the closest relationship, and where a couple of his serials had been published. Where once he had walked freely into the office of the newspaper – the leading newspaper among the most established ones – this time, the doorman asked him, “Who are you looking for?”

Who was he looking for? Who was he supposed to look for? He told the doorman that he’d like to see the editor-in-chief.

“Who, may I ask, is looking for him?”

He told him his name. Even the doorman must have heard of him, since he stood up with respect, and said, “Yes, sir”.

He called the editor-in-chief, and then he said, “Please come in, sir, he’s waiting for you.”

He entered the editor’s room. He knew him, but not well.

The editor greeted him with respect. Standing up, he walked towards the door, shook his hand, and showed him the chair. He asked what he’d like to drink, what would he like?

“I’d like to have a coffee with a little bit of sugar.”

What if the editor asked him, “May I ask the purpose of your visit, sir?” No, he wouldn’t ask him that way. He treated him so respectfully that at worst he’d ask, “How may I be of service to you, sir?” What would he say then? He couldn’t say that he’d come to ask for a job, could he? In order to avoid such a question, he said,

“Sir, I like your articles very much, I admire them.”

“That’s very kind of you, üstadım…”

“I enjoy reading your editorials every day.”

“Thank you, üstadım…”

“I was just passing by, I thought I’d better pay a visit.”

“You’re so kind, üstadım…”

“I hope I’m not keeping you…”

“Estağfurullah, üstadım, I’m honoured.”

The coffees were finished, the small talk was over. So? What now? Surely the editor would understand why he had come. After all, the man who hadn’t visited this newspaper for so many years wouldn’t show up for no reason. He would understand, and then he’d say, “I wonder if you have a novel ready, sir, if you would be so kind to publish it in our newspaper.” And he’d say something along the lines of, “I don’t have anything ready, but I have two that I’m currently working on, one of which is almost finished.”

Their conversation didn’t go in that direction at all. For the sake of conversation, he said, “You’re active in politics, you’d know. What do you think of the prime minister’s latest speech?”

He wasn’t listening to – or didn’t understand – the editor’s thoughts. He’d been sitting there and they’d been talking for quite a long time, but the editor hadn’t requested an article, a novel, or an op-ed.

“Well, I should go now. I’ve taken too much of your time.”

“You’re most welcome, üstadım, I’m glad you stopped by. Please come see us again, üstadım.”

As he climbed down the stairs, he was thinking: He’d said, “Please come see us again, üstadım.” What did it mean? The editor was clearly inviting him. He couldn’t request an article from him on his first visit, could he? It’d be disrespectful. But it was obvious that he’d certainly do so on his second visit. Maybe it wasn’t his job to request articles.

He visited another newspaper. This time, he was going to see the owner. He knew his late father very well, he’d been friends with him. They’d talk about him and their memories of him, so there’d be no trouble in finding a subject to talk about.

“Who are you looking for?”

He wanted to see the owner of the newspaper, but the man was currently in Europe. Rather than going away, he lingered for a moment. Then he said, “Can I see the editor-in-chief, then?”

“Who, may I ask, is looking for him?”

He said his name.

He talked to the editor of that newspaper about similar things that he had talked about with the editor of the previous newspaper. Unlike the previous editor, he told this one that he once wrote op-eds for newspapers, hoping he’d request one from him.

“You might not remember those days.”

“Not at all, üstadım. Of course I remember. I used to read your op-eds every day. There are pieces of yours that I had cut out and kept, and still haven’t forgotten.”

“Journalists these days… Well, I don’t know how to put it. It’s a different thing to write a proper op-ed. It’s a hard job.”

“My dear üstadım, whatever happened to those op-ed writers of your time?”

He thought of saying, “Are you blind? One of them is here, right in front of you!” But he couldn’t. It would be inappropriate.

As he left, the editor had said, “You’re most welcome, üstad, please come see us again.”

He spent the entire week visiting one newspaper or magazine after another. He met with the owners, editors, columnists, secretaries. To some, he mentioned translations and commentaries, he talked about novels. Wherever he went, they saw him off with, “Üstadım, we hope to see you again soon.” “Üstad” went to the places hoping to see him again a second or third time, but nobody offered him any job or requested an article. Maybe they were being hesitant out of respect. Or maybe they assumed that the renowned author was well off, and that he didn’t need to work. Eventually, he decided to ask for a job outright. From his experience working in newspapers when he was young, he knew very well that there was fierce competition between the editor-in-chief, columnists, management, and staff responsible for technical issues. They wouldn’t hire him for such positions. Granted, he wasn’t interested in any of these positions. An insignificant job that would help him make ends meet would suffice.

Again, he started making the rounds of the newspapers and magazines. By calling him üstadım, dear üstadım, they were pouring so much respect over him that he could not tell them he was having a hard time making ends meet. But he could tell them other things: he got so bored of sitting at home doing nothing… He was not that old, after all… He was at an age where he could still work and be useful… He was bored of not having a job… If only there was a small job for me…

Suddenly, the editor-in-chief said:

“But üstadım, estağfurullah, how could it be possible? Estağfurullah… I would be ashamed to even mention it. There is no job worthy of you in this paper. Estağfurullah… How could a small job be good enough for you? Even the big ones are not worthy of you. Estağfurullah… ”

As he was leaving, the editor-in-chief said, as before:

“Please come visit again, üstadım.”

He went to another newspaper. This time, without coming up with any excuse like boredom, he told them straight away that he was having a hard time making ends meet. Was there any job for him, something like proofreading, something that they would think of hiring him for?

The owner of the paper said:

“Forgive me, üstadım, how could that be? How could proofreading be a job worthy of you?

He got his hopes up. If not proofreading, another job would do.

“Forgive me, üstadım, we wouldn’t dare think of it. We would be ashamed. Estagfurullah…”

He went to another newspaper. There, he spoke more openly. He hadn’t been able to pay his rent for the last three months, he was in debt. Any suitable job, he was ready to do anything, he had to. Over the years, he had worked in every area of journalism.

“Out of the question! You don’t mean to insult us, üstadım, do you? Estağfurullah… Unthinkable! How could it be? Someone like you…”

He went to another newspaper. He had to speak even more openly. He had to speak the truth as it was. He was in a bind. He had even sold all his suits except for the one he was wearing. What else could he say? He wanted a proofreading job, even on the night shift…

“Forgive me, üstadım. Estağfurullah… How could it be? For you? For a famous, established author like you. My God! This would be an insult to you. Estağfurullah…”

At first, he had even taken pride in hearing “Estağfurullah, üstadım.” But he gradually came to understand that all this flattery was an excuse to get rid of him. Even though he understood this and knew that they wouldn’t offer him a job, he still visited the newspapers and magazines to ask for work because he liked to hear “Estağfurullah, üstadım” and because he wouldn’t hear such praise anywhere else.

“Estağfurullah üstadım!” they said.

His only solace was in hearing these words.

“The Secret” by Murat Gülsoy

Murat Gülsoy (1967–) was born and raised in Istanbul, where he also attended university. He completed his doctorate in biomedical engineering in 2000, but has been publishing short stories and essays since 1992. He has written 18 books to date, including 8 novels – several of which have won prestigious literary awards.

Taking a deep breath, I knock on the door. It’s eight o’clock. I’m right on time. I’m terrible at being late.

“Nur. Welcome, sweetheart.”

As Zerrin Hanım gives me a quick peck on each cheek and lets me inside, I notice there is no one in the room.

“Am I early?”

“Early? Not at all! Don’t you know these people? None of them ever comes on time. I will tell Hasan to make a round.”

That’s true – as if it isn’t the same every time, as if every condo meeting could ever be a fresh start. I show up at the door with my computer and printouts right on time. Zerrin Hanım opens the door with the bell ringing like birds chirping merrily and I deliver the same lines. Curvatures in space-time appear before my eyes, with Zerrin Hanım and me standing face-to-face in the doorway at different times. In most of them, I’m wearing the same jeans, sneakers, polo shirt, dressed like a man, but Zerrin Hanım is different in almost all of them. Only the reading glasses hanging from her neck are the same. She’s definitely wearing one of her dresses from her days as a bank manager. There must be so many of them; they never run out. But it seems that she has a hard time fitting into some of them. This is our fifth year in this condo. Our first home, the one where Selim carried me over the doorstep. Happy and seductive in my white wedding gown, Selim had lifted me like a feather with his strong arms. We crossed the threshold into married life with him stepping with his right foot; the angels of love, in the form of chubby babies, clapped their hands with joy over our heads! Selim and strong arms – ha! Don’t make me laugh. I can’t help but make ridiculous jokes on my own. It’s a strategy for survival.

After glancing at the empty chairs in the room, I sat at the table and turned on my computer. That’s my place. The pictures inside the glass china cabinet, the main piece of the sitting room furniture set, have not changed. The family members are all in place: the enlarged and framed picture of the son wearing a cap with a victorious smile taken for the yearbook; the mother and father of Zerrin Hanım at a wedding party or in a seafood restaurant, in black-and-white, from the glamorous 1950s; young Zerrin Hanım with a pompadour hairstyle; and my favourite, the picture of Baha Bey taken while fishing on a boat, looking happy, energetic, healthy. The right-hand side of the cabinet, however, holds the pictures that I don’t like much. The pictures taken of Baha Bey with politicians and businessmen at various parties. When I look at this side, I feel the same kind of pity that I feel for restaurant owners who find joy in hanging pictures of celebrities that came to eat at their place. But I don’t feel the same compassion towards the Baha Bey in these pictures. I don’t like the way he is in the world of the filthy rich.

“How is Baha Bey?”

Zerrin Hanım took a deep breath.

“There was another attack recently. They have become more frequent these days.”

“What does the doctor say?”

“Nothing. He is almost 90.”

“Is Baha Bey that old?”

I was truly surprised. He didn’t look his age at all.

“Our age gap is quite large. Baha turned 87. His blood vessels have swelled like boiled pasta, of course. On top of that, they’re clotted. Blood thinners can only help so much. When there’s a lack of blood flow to the brain, attacks occur. By attacks, I mean minor strokes.”

“How is he now?”

“Good, he’s taking a nap. He should wake up soon. He’ll watch tennis tonight.”

I had completely forgotten about Nadal’s match. Tennis is our favourite sport to watch. We do our best not to miss any matches even though neither Selim not I have ever held a tennis racket. I felt sorry for Baha Bey, even more now that we had something in common. I felt uneasy because of all the negative thoughts I’d had a moment ago, and immediately glanced at the picture taken while he was fishing. Where was it taken? The boat seems so steady that it could not be the Bosphorus. Maybe Büyükada… It’s almost evening, and the weather is partly cloudy, like the sun in August…

“Should we perhaps meet another evening?”

Zerrin Hanım put one platter filled with cookies she bought from Gezi Patisserie (I shouldn’t eat, I shouldn’t eat…) on the coffee table and another on the dining table, and wrinkled her forehead.

“No, no, we’d better get it over with. I can’t change my schedule because of Baha. Tea, coffee, something cold? What would you like to drink?”

“Please don’t trouble yourself… I can get it myself.”

The words I uttered out of politeness quickly dissolved in Zerrin Hanım’s wind. As if she would allow others in her kitchen.

“It’s no trouble at all. I’ve just started making the tea. Thinking they’ll probably be late anyway. It should be ready soon. But if you like, I can also make coffee. The water is ready.”

Them. I was also one of them until I stepped through that door just a moment ago. I fidgeted uneasily. In order to get rid of this feeling, I turned on my computer. I checked the wireless signal strength. Our router—CaptainPicard—showed one bar, weak but good enough, better than nothing. The computer connected automatically. Zerrin Hanım’s router signal is strong, but I don’t know the password and I don’t want to ask. One neighbour needs another neighbour’s wireless… but it’s impolite to ask. The rules of etiquette of the new world have yet to be defined. You’re not funny at all, Nur. Be serious. Zerrin Hanım sat on the most commanding chair in the room and crossed her legs. Maybe you should take some cues from her. A director’s way of sitting. Distinguished. A respectable form of existence that brings men to their knees with a magnetic look or sophisticated words, and makes you feel like you’re dealing with a professional. I tried to imagine myself in her shoes. Nur Kılınç Arbaş, in the bank, behind her desk, her hair styled, a paisley scarf around her neck that matches her dress, with natural-looking makeup and high heels. Adding Selim’s surname to my maiden name resulted in this oddity. It’s horrible! I can’t think of myself as a director anywhere. I only have two pairs of high heels. I’d bought one of them for the wedding, and the other on a silly whim. How many times have I worn them anyway? Zerrin Hanım, on the other hand, was born in them; they were created to continue the elegant curves stretching from her legs to her toes. Stilettos… Looking at the way she sits, her posture, the way she watches the smoke of the cigarette with misty glances, no one could guess that she is a woman looking after a paralyzed husband twenty years older than herself. “The woman of curves” looked with contempt at the set of objects on the table, including the record of meeting minutes, the receipts, a calculator, and folders of expenses. All those files, clients, branches, and accounts that I’ve dealt with all my life… She placed a cigarette in her cigarette holder. I can run circles around all of you. You can do it, Zerrin Hanım. You’d knock spots off anyone but alas, you’re chained to this house, to this life, by your elegant ankles. I, on the other hand, plunge into the modern city life in my sneakers, blue jeans and with my tomboy haircut. I float freely all day, and then… And then, of course, I return home. To my home, located at the same coordinates as yours.

“Let’s have a smoke before they come. Otherwise, they’ll be bothered by it…”

In fact, I don’t smoke either, but in order not to be included among “them” I try not to give myself away. It occurred to her after she lit up.

“Oh, you don’t smoke, do you?”

“No, I mean, occasionally.”

I started to blush again.

“Better not to smoke at all, but I only have this one pleasure. You are doing the best thing, sweetheart. I didn’t smoke at all until Doruk was born. But you know the working life: at some point you feel obligated. It was like that back then. How is business at your company?”

“Good. Not bad.”

“So, what exactly does your company do again?”

I repeat my answer to the question she asks every year, but she can never remember the answer, or doesn’t feel the need to remember.

“Information technology. We set up computer hardware and operating systems for big companies.”

The doorbell rings before I can finish my words. The button was pushed so hard that the canary sang over and over. Zerrin Hanım stands up and walks towards the door; she’ll ask the same question next year. I was left alone in the room. In the sitting room, not in the family room. This is the largest room, the +1 of the apartment that would be advertised as 3+1. I start to stare at the landscape print hanging on the wall, which was originally painted by God knows who and had been reproduced a million times. To be honest, it’s very beautiful. A cabin built next to a lake or a stream, with wispy smoke coming from its chimney, snow-capped mountains in the distance, the crimson colours of sunset… We all want to be there, don’t we? I’d seen it in a documentary. I remember Atatürk, sick in bed, looking at a landscape painting in front of him and saying, “We will go there one day, won’t we, child?” and I can’t hold back my tears. The touching voice of narrator Can Dündar shattered my innocent soul, which was just going through adolescence. We watched it as a family; trying not to show that I cried, I went to the kitchen and drank some water.

I hear Madame Anjel’s and Ferhan Bey’s voices. They arrived at the same time. Turning my head, I see that they’ve entered the room. Ferhan Bey wore a loose white linen shirt and wrinkled, cream-coloured summer pants. Madame’s hair is tied back. She lays her eyes on Zerrin Hanım. The bags under Madame’s eyes were even more swollen than last time. She’d applied green eye shadow, not caring about her age. Good for her! She greets me gracefully.

“Good evening, efendim.”

“Good evening, how are you?”

Madame doesn’t speak without the honorific efendim. She gives me the impression that she’s from another era. Parallel universes. We may live in the same building, she may be 40 years older than me, but how much of a difference is it relative to history, anyway? There’s an analogy that goes like this: “If the time that has passed since the beginning of the world were to be represented as the Empire State Building, then the time since the emergence of humans would be equivalent to a postage stamp placed on the antenna at the top of the building.” Human history is so recent… If Selim heard this, he’d ask whether the stamp lay flat or stood upright. İlhan would object by saying, “Does a stamp stay upright?” and they’d argue about it until the next morning. We haven’t grown up yet. We refuse to grow up. Everything we do is tainted by confusion and clumsiness. So, what am I doing here? Maybe I’m trying to get away from them. From Selim, from İlhan, from that whole boys’ world. From the smell of the cafeteria in the engineering faculty that clings to me. Meanwhile, Madame prepares to give a dramatic answer to the question I asked just for the sake of conversation.

“How else could we be? With things the way they are, how else…?”

Deep sighs. I’d never seen Madame this sad. Ferhan Bey also lives in another time. As if he were enchanted, he walked towards the balcony door as soon as he entered the room, slowly pulled one side of the curtain open, and, rising on his tiptoes and turning his head to both sides, looked outside. I don’t know how he knew that I was looking at him, but to satisfy my curiosity, he began to explain:

“We could see the sea from here before Iron Estate was built. The historical peninsula was right in front of us. Scoundrels… It’s no Iron Estate, it’s an Iron Stake.”

The same old talk for the last five years. The threads dangling from the hems of Ferhan Bey’s pants catch my eye. This must be what growing old alone looks like. For a man. For an alcoholic man. Would Selim turn into a man like this after I’m gone? But he doesn’t drink much. Only coke could make a hole in his stomach. Most importantly, Selim won’t inherit apartments from his family and he doesn’t have any money in the bank, and it’s highly unlikely that he ever will, so he has to work. Ferhan Bey sits down forlornly by the cookies. He nibbles on them without even realizing it. This is awful, I feel like I’m witnessing my future with Selim, who’s waiting for me to return home to watch Game of Thrones. Stop eating, Ferhan Bey, stop eating. Meanwhile, Madame continues her grumbling.

“This is not good, not at all. The porter is not around. Even if he were, what good would it do? They’ve gotten out of control again. It’ll be us paying the price, it’ll be us.”

I tried to explain why the protests triggered by the Gezi Park events were an appropriate response. Madame Anjel shrugged, dismissing every word of what I said.

“They go wild and then provoke others to get involved. People take to the streets because of them.”

“My dear Madame, it isn’t as you think. The president has pushed people to such extremes. He called them looters, can you believe it? Enough was enough, the nation has come here. The people have taken a stand…”

I wasn’t sure if Madame Anjel understood what I had just said. She was staring ahead in front of her, talking to herself in a murmuring tone.

“The public… You can’t trust the public. It’s impossible… They can chop anyone into pieces, then throw them into a pit for their own benefit. We are all heading towards yet another event like that of September 6th and 7th.1 Everything came to an end in one night, one single night… They brought in men from Anatolia in large trucks. They burned everything down, smashed it to the ground. Now it will be repeated all over again…”

“What does all that have to do with this? This is a very different thing. They have no connection whatsoever. Those who support the Gezi movement are trying to prevent such destruction. They want to preserve the park as it is. They don’t want anyone to meddle in their lives. They advocate for democracy; they want people to live their lives as they wish, as they believe fit. They don’t want anything else.”

“How do you know? Do you know who those people are?”

I was losing my temper.

“The people who support the Gezi movement are the same ones who attended Hrant Dink’s funeral.2 They are risking their lives, even dying, for what they believe.”

I couldn’t recognize my voice as I was saying these things. It rang out shrilly, like the voices of those women who jabber naively when a microphone is extended to them during street interviews on TV. Madame Anjel glared at me.

“What do you know, huh?”

There was something dark in her gaze that I couldn’t understand. As if she were hiding a terrifying secret. It was as if she had long forgotten the words to tell the secret, as if the secret were stuck slamming against the walls of her mind like a trapped pigeon.

“Do you know what Gezi Park used to be?”

We fell silent when Zerrin Hanım walked into the room carrying a tray with the first tea of the evening. Of course I knew what it used be, so I stayed silent. But Madame did not.

“It used to be an Armenian cemetery. Underneath any stone you move in this country is an Armenian grave.”

My face turned red. Madame Anjel was living in one time, and I in another. Ferhan Bey took his tea and to change the subject, he lavished Zerrin Hanım with compliments. Meanwhile, there was a knock on the door. The other neighbours finally showed up. My mind stayed on Madame. This whole struggle, this game of tag with the police, the pepper spray, the tweets, the solidarity, the democratic discussions where we became one single body… she saw something else when she looked out at the street. I remembered the body of Hrant Dink lying dead on the street. My eyes filled with tears. (That photo. God damn it. What a cursed, dark country this is! But it’s not only filled with murderous souls; we are here too… Okay, maybe we’re not the majority, but we still exist. We’re the ones who started tagging the subtitles of the pirated version of Game of Thrones with #resistgezi, the ones who marched the streets chanting, “We’re all Hrant, We’re all Armenians,” the ones who painted the stairs in the colours of the rainbow, and the ones who sat at on the ground at tables a hundred meters long every evening at iftar. Indeed, we are not the majority, but the minority. Just like you, we are also the minority in this country. Yet the whole world said, “Good Job!” when they saw the way we resisted…) When I realized that I was ranting in my head in response to Madame Anjel, I felt ashamed. I was getting angry in vain with one of the last remaining members of a community who had been ripped like weeds from the soil on which they had lived for thousands of years. What right do I have to tell her how to think? To distract myself, I texted Selim: “You start watching, don’t wait for me.”

Somehow, all the residents were there. Zerrin Hanım welcomed everyone to their seats, served them tea, and took her place at the head of the table. I was sitting next to her as her assistant and was sharing the details of the report. Two issues were at the forefront. The first one was brought up by our handsome, well-to-do neighbour, Hakan Bey, who asked, “Shall we have them rebuild the whole building as part of the urban transformation?” and the second one was the new father Burak Bey’s problem with cats. ecause Hulya Hanım couldn’t attend at the last minute due to a migraine, the cat issue couldn’t be discussed. Ferhan Bey was the strongest opponent to giving the go-ahead to the contractor for rebuilding. And this was understandable. After all, it had been built to house only one family, but over the years it turned into our circus of five unrelated families. Besides, once rebuilt, the size of the units would get smaller, the ceilings would get lower, and the whole building would lose its originality. Madame also sided with Ferhan Bey. She said her only wish was to die in this house. When Sevinç Hanım, who kept checking Instagram on her phone throughout the meeting, also opposed the idea, the issue was dropped. And the residents left one by one. Only Madame Anjel, Ferhan Bey and I remained.

I was going over my notes one last time. I think it was right when Zerrin Hanim asked if anyone wanted another cup of tea. We heard a sound come from inside, a sound of something hitting the floor. Startled, Madame Anjel and I looked at each other. Baha Bey was the only one inside. Something had happened! Something bad!

As Zerrin Hanım ran inside, yelling “Baha! Baha!” I sprang up after her without thinking. As I passed through the hallway darkened by brown and green shadows, I realized that I was seeing the photographs showing the happy moments in Zerrin Hanım’s, Baha Bey’s – and of course, Doruk’s – lives for the first time. Since the guest washroom was right next to the sitting room, I hadn’t stepped into this part of the apartment before. This was a journey into the secret parts of the Zerrin-Baha family’s life… It felt as if I were in a mind that was not my own. As I walked on the navy and red carpet in the hallway, I thought of how soft it was. All the while, Zerrin Hanım’s heart-wrenching cry was ringing in my ears. “I’m here, Baha… I’m here…” My stomach began to ache as it always did whenever I became nervous or panicked.

The first thing I noticed when I entered the room was the smell: of lemon kolonya and of the sick, old man. The acrid smell of rotting meat. Bad breath. Maybe he was also soiling his pants. No matter how many times the bed was cleaned, the sour smell of urine persisted… I felt sick to my stomach. This room corresponded with the large room that opens to the balcony in our apartment upstairs, which Selim and I use as an office.. A calendar showing three months at a time was hanging above the single bed, right next to a clock and a calligraphic Basmala3 framed by marbled paper. On the flat-screen TV on the wall across from the bed, Nadal was about to serve. The soft light of the pomegranate-coloured bedside lamp, which must have come from an ornate bedroom set, reluctantly illuminated the body of Baha Bey lying motionless on the floor. He had clearly tried to stand up, lost his balance, and fell.

He was dead.

My nausea was almost out of control. I tried not to look at Baha Bey, but no matter what I did, his thick, yellowed toenails stayed within my view.

Was this really a corpse now? Baha Bey’s lifeless body?

Zerrin Hanım was in tears, bending over the corpse lying face-down on the floor in pajamas, trying to do something. I was thinking that her efforts were vain, and came to my senses when I heard her call, “Nur! Hurry, get me his pills. Quick. He’s having an attack.” The small coffee table in front of the TV was full of pills. While I was trying to pick the right one, Zerrin Hanım was struggling to turn Baha Bey over onto his back with a superhuman effort. Madame Anjel was also bent over, helping her and shouting, “Ferhan!” Zerrin Hanım was trying to turn the old man’s heavy body towards her with unexpected strength, with one of her shoes having almost fallen off, its long heel broken. There was a run in her stockings where her knee met the floor. Her foot must have been hurting, but she didn’t seem to feel it. Finally, she managed to turn Baha Bey onto his back, his head was now resting on her lap. I could see his chest heaving. He was not dead, but he had a blank look on his face. He was bleeding from his forehead. His dark blue and khaki striped pajamas didn’t have a collar, and had quite a modern cut, but his face seemed swollen. The image of the self-assured, permissive, vigorous father in the photographs was gone, leaving behind a sick man close to death. Madame Anjel went to the kitchen to bring some ice. I admired her composure when dealing with such a tragic situation. I decided to be a cool woman like Madame when I get older, but I wasn’t sure that I could even do it… So then, would I leave Selim on the floor like this, believing he’s dead? Would I, really? What would I do? Would I call his family and tell them, ‘Your son is dead, come get him’? I think I would be expected to cry. I would cry.

My hand was shaking as I handed the pills to Zerrin Hanım. She broke the capsule under his tongue. Her manicured fingers, which not long ago had been elegantly holding a cigarette, were now occupied with pill capsules. I was telling myself to learn these things, to learn how to be feminine. Madame Anjel returned with ice cubes wrapped in a napkin. As she dressed the wound on Baha Bey’s forehead, she yelled to Ferhan Bey – who was taking his time – “The man is dying, all hell is breaking loose, where are you?” Ferhan Bey looked as if would throw up from the vodka he had drunk, with his watery eyes and his forehead covered in sweat. A thought crossed my mind that the whole situation would be complete if he had a heart attack, but he proved me wrong. He approached like a man who knows what he’s doing, gently went behind Baha Bey, and lifted the old man onto the bed. Baha Bey closed his eyes. Zerrin Hanım took his hand into hers. I asked apprehensively:

“Is he okay now?”

Zerrin Hanım shrugged.

“I don’t know. With each attack another part of his brain gets ruptured or dies. Or something like that. The doctor said no one can tell when these attacks will come, or what damage they’ll do. The blood vessels get clogged. The blood doesn’t reach the brain. Then the brain slowly dies. Slowly… If someday it happens in a vital place… Then…”

She began to cry. Ferhan Bey took Zerrin Hanım’s other hand into his with a gentleness I never expected from him.

“Don’t cry. If you give up, he will too. People in these circumstances feel it…”

He was mumbling. Were these the deceptive feelings of drunkenness? Madame Anjel agreed, “You must be strong. While there’s life, there’s hope.”

This sentence, which I remembered from old Turkish movies, didn’t sound strange to me at all now. Zerrin Hanım wiped her tears.

“Everyone thinks I have a hard time looking after him. No… No, I can’t live without him. 38 years… Easier said than done. I don’t even remember who I was before him.”

My eyes also filled with tears. Madame Anjel poured a glass of water and gave it to Zerrin Hanım. Ferhan Bey stood up, left the room, and started walking slowly down the hallway. He was going back to the sitting room, probably to drink the last bit from the bottom of the bottle. Madame started talking with a gravelly voice.

“The one who spins the thread of destiny is the one who knows when we will go. When it’s over, there’s nothing you can do. However much is cut, that’s what we will live. Not a centimetre more or a centimetre less.”

I wanted to give in to the soothing effect of this way of thinking, but I couldn’t. If it was a hundred years ago, there wouldn’t be these pills, or anything else like that… Both Baha Bey and Zerrin Hanım, and even I, would be dead. Many years from now, we’ll say, “Poor thing, they were so young.” about those who die at a hundred. I wanted to say, “We keep adding to the thread of destiny, my dear Madame,” but …

As my heart rate slowed down with my quiet train of thought and my mood returned to normal, Baha Bey’s eyes opened. He began to speak, but it wasn’t clear what he was saying. It was like the meaningless gibberish of those who talk in their sleep… Then I realized that he was murmuring something like a lullaby. In another language… I heard Madame Anjel say something in an astounded voice. She brought her hands to her chest. “He’s speaking Armenian,” she said. Her voice was strained. Zerrin Hanım was shaking her head from side to side. I didn’t understand what was going on. Curious, I asked Madame Anjel:

“What’s he saying?”

“He’s singing a lullaby… ‘Sleep, my little lion, sleep. It is almost morning. Your dad is watching us. Sleep, my little lion, sleep.’”

Enchanted, we all listened to Baha Bey’s lullaby for a while. Madame Anjel held Baha Bey’s hand and said something to him in Armenian. I don’t know if Baha Bey understood her, but his lullaby gradually faded away. He closed his eyes and fell asleep. His breathing was back to normal.

Madame felt the need to explain to us, “I said, ‘Sleep, my son, your mother is here.’”

I only realized that Zerrin Hanım was crying when I saw her wiping her tears. Those tears were brought on by a different kind of sorrow.

“Madame, Nur, can we keep this between us?”

This? Something to remain between us… Madame sighed deeply. Zerrin Hanım continued, “Nobody knows. Not even Doruk… Especially not Doruk.”

Then I understood what she was talking about. I blushed with embarrassment. I couldn’t look at Madame Anjel’s face. Zerrin Hanım explained that Baha Bey’s family was Turkified long ago, but when he was a child, they would speak Armenian at home. Oddly, Baha Bey was now reliving those days after each attack. His mind wavered, and he sometimes did these sorts of things, like speaking Armenian, singing nursery rhymes… Agitated, Zerrin Hanım said all this hastily. In her movements, there was the rush of someone caught red-handed. She kept bringing up Doruk’s name. Doruk should never learn that his father was an Armenian convert. He wasn’t ever supposed to know. As a matter of fact, no one should know. Yes, it was a lie, but a white lie that wouldn’t hurt anyone. The whitest of all lies. We nodded our heads in sympathy. Trying not to step on her broken heel, Zerrin Hanım stood up. Her mascara had left black lines on her face. The nail of her pinky finger had broken. Her appearance made everything seem more dramatic than it was. Madame Anjel tenderly patted Zerrin Hanım’s back. She said something that brought tears to my eyes, something that wouldn’t have moved me if I had heard it under different circumstances:

“We’re all human.”

Leaving Baha Bey in the arms of a peaceful sleep, I took a deep breath as we returned to the sitting room that smelled of jasmine perfume. I felt relieved, as if I had walked outside into the open air. Ferhan Bey had passed out on the couch. Zerrin Hanım spread a blanket over him. Madame Anjel was sighing deeply as if she were praying. Now this sitting room, this house, the photographs, Madame Anjel, everything looked different to my eyes. I felt a knot growing in the pit of my stomach as I looked at Doruk’s photograph where he was standing next to his parents, smiling to the camera on his graduation day. He would never know the past. Baha Bey’s secret had penetrated the reality that was surrounding us and torn it to pieces. A black hole had formed. Everything was being snatched into the vortex around it, swirling into it. I felt awful for having argued with Madame Anjel earlier in the evening. There was another world behind the one we see. The hidden history of the oppressed. All those things that were denied, that couldn’t be talked about, that were unexpressed, that were unremembered, were wrapped around us without our noticing, leaving us still and breathless. Rotting away from the inside out… All that history, which I had found unnecessary to think about until that moment, manifested in front of me in the form of Zerrin Hanım’s life. I wanted to apologize to Madame Anjel, but my eyes were drawn to the ground like small balls of lead, and I couldn’t turn my gaze to her. It was as if I were in a dream. I popped one of the tiny dill pastries that were on the coffee table into my mouth. They were from Gezi Patisserie, salty and greasy as always. This familiar taste, which would upset my stomach in two hours, was calling me back to the present moment. There we were, once again in Zerrin Hanım’s sitting room. Baha Bey had been restored to being a sick man who suffered from recurring strokes. Zerrin Hanım took a bottle of liqueur from the cabinet. “Homemade,” she said. She poured it into small, elegant crystal glasses. We each drank a glass in silence.

1 The events of September 6th and 7th, commonly known in English as the Istanbul Pogrom, were a series of mob attacks directed primarily at Istanbul’s Greek minority in 1955, resulting in many casualties and extensive property damage. The events were triggered by a series of false news stories igniting hypernationalist sentiments and by the economic crisis in the country.

2 Hrant Dink was a Turkish-Armenian journalist and peace activist who was assassinated in Istanbul in January 19 2007 by a Turkish nationalist. He was a prominent member of the Armenian minority in Turkey.

3 “Basmala” or “Bismillah” (written in Turkish as “Besmele”) is an Arabic phrase meaning “In the name of God.” As it is often recited when undertaking everyday activities, especially prayers, it is one of the most commonly used phrases in Islam. In the Arabic calligraphy art form, religious phrases like this one are quite popular, and works of calligraphy are used to decorate homes. The narrator in this story is referring to such a piece – “Basmala” written in ornate Arabic calligraphy surrounded by marbled paper for decoration – on the wall in Baha Bey’s room.

Selected poems by Gülten Akın from her book Beni Sorarsan

Gülten Akın (1933–2015) was an influential poet who enjoyed a long career spanning almost her entire life, publishing 13 collections of poetry from 1956 to 2012. Some of her poems were turned into songs, most famously “Deli Kızın Türküsü,” which was first recorded by Sezen Aksu. We translated several of Gülten Akın’s poems from her final collection, Beni Sorarsan, to contribute them to a special issue of Turkish Poetry Today dedicated to this last book. Some of our translations can be found in that issue, and the others are here.

IF YOU’RE WONDERING HOW I’M DOING

If you’re wondering how I’m doing,

Winter is here

The days of the heart’s grief have come

The world has withdrawn into homes, into itself

Between the yellow jasmines and the roses

Between the purple spring of the mountains

And the fog

Between the sea and the lake

Cats, birds by my side

I’m wandering out of my thoughts

Although I have no love for power,

Girls could somehow grow up

Calm, well-behaved, waiting for death

Smashing and crashing

Under the power of the woodstove

Old age

Did they become giants, the others

Coming and coming at them, fearless

They are testing their strength

US

Better than the freedom that you granted

is the prison that you put us in

the world will blossom for good

when we rebuild it.

the hope you give

kills the deer that drinks it, the fish that swallows it

POETRY

Poetry is my old partner-in-crime

Whatever we did, we did it together

BERLIN

They think that rain does not erode stone

But it did

Does the other one stay the same?

The city I used to visit, now

Berlin is like any other place

It was time itself, and time eroded it.

FAREWELL

I’m tired, I’m leaving

You choose your own worries