Everyone knows ducklings: yellow fuzz, big flat bills, big flat feet, cute little waddles all in a line after Momma, and superpowers.

What, didn’t you know that last part?

Death-defying leaps!

Several duck species nest high above the ground in tree cavities. This is safer than nesting on the ground, predator-wise, but it also means that the ducklings hatch very, very high up. And then they have to get down.

When they hatch, the ducklings weight very little, which helps: the less you weigh, the less you are hurt by falling. Terminal velocity—the fastest that gravity will make you fall—depends on weight, so small creatures are essentially safe from falling no matter how far they fall. The cushiony leaf litter on the ground helps the ducklings too. And notice how they flatten out, spreading their little legs out behind and their wing stubs out front, their bodies as spread out as possible: they are gliding—albeit not as well as a true glider like a flying squirrel, but nevertheless slowing their descent so that they can land safely.

Want to see that again? I thought so:

–

Epic journey of the adorable orphans

Ducklings, like other precocial and nidifugous baby birds, can walk around and feed themselves soon after they hatch. Mom is therefore not so much a provider as she is a sheepdog, herding the ducklings toward safe places and defending them from predators. This is still a very important role: anyone who has watched local duck families over the course of a season knows that the number of ducklings tends to diminish rather rapidly, so that a flotilla of twelve new-hatched ducklings may become a group of four by the time they start to grow in their adult feathers. It’s a scary world out there for small, delicious birds, and they need Mom’s protection.

Nobody’s getting at these Common Goldeneye ducklings without going through Mom first.

Photo by Geir Friestad*

But what if they don’t have that protection and guidance?

In 1988, researchers studying Mallards captured a female, banded her, and attached a radio transmitter. They monitored her as she nested, laid seven eggs, and incubated them. After the ducklings hatched, the researchers attached individually-numbered web tags (little metal tags attached to the skin between the bird’s toes) to each duckling, as well as radio transmitters to two of the ducklings. So far, so normal.

That night, a red fox killed the mother duck. The ducklings, still in the nest, somehow escaped the fox’s notice. They waited in the nest until late afternoon the next day; then, they left. Ducklings should be led by their mother from the nest to the relative safety of water soon after hatching. These ducklings didn’t have Mom to lead them, but apparently they still had an idea of what they should be doing.

Not the same ducklings, but these ones got trapped in a storm drain and had to be rescued, so they had an adventure too.

Photo by Rona Proudfoot*

What follows, described in professionally dry language in the paper by Krapu et al. (1991), must have seemed like a journey on par with a fantasy epic to the ducklings. They all stayed together: ducklings imprint on their brood mates and like to stick together. Apparently unable to sense where the water was, they didn’t manage to head towards the closest water. They spent the night on dry land, vulnerable to foxes, squirrels, mice, rats, weasels, and other such terrors. The next morning, they had to climb a steep hill. Then one of the transmittered ducklings was killed by a Swainson’s Hawk. When the surviving ducklings finally reached water that afternoon, their trip had lasted ten times longer than the normal nest-to-water trip for Mallards.

Still, alone and not yet three days old, they made it.

Getting tagged while still inside the egg

This one might be more a superpower of some clever researchers than of the ducklings, but it’s still pretty cool.

Ducklings are often marked with web tags to distinguish individuals, similar to how I mark the juncos with leg bands. I have the luxury of being able to band junco chicks any time over a few days, since there is some time between when a junco chick is big enough to band and when it is ready to leave the nest. Ducklings, however, are ready to leave the nest within a few hours after hatching, making it very hard for researchers to tag them before they disappear into the underbrush.

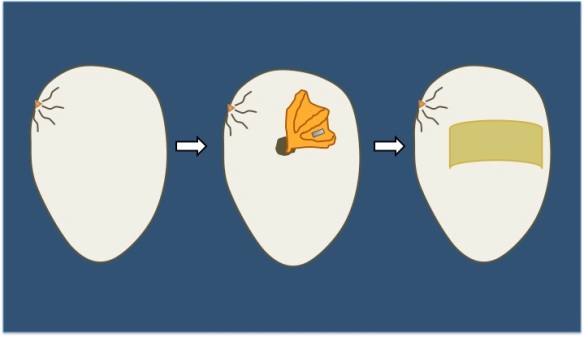

One solution? Tag the ducklings before they hatch. Alliston (1975) found that, since ducklings always take up the same posture inside the egg, and since the two ends of the egg can be distinguished (one is slightly pointier), it was possible to figure out exactly where in the egg a foot should be. First you wait until the ducklings pip—make a little hole in the shell with their bill—since that tells you where the head is, and also that the duckling is fully developed and about to hatch. Then you can figure out where a foot should be, cut a little hole in the egg there, pull the foot through, tag it, tuck it back into the egg, and cover the hole with masking tape.

Tagging an unhatched duckling. The tag is the little metal thing on the foot. After Fig. 1, Alliston 1975.

The duckling hatches normally, pre-tagged.

I wish you could do this with juncos—mostly because the egg with nothing but a little foot sticking out looks so funny.

Leaping stairs in a single bound

Well, eventually.

–

Some conferring with my colleagues yields a split between calling these baby Common Mergansers “ducklings” or “mergoslings,” but I’m including them anyway.

Photo by Liz St. Jean Photography*

*Photos obtained from Flickr and used via Creative Commons. Many thanks to these photographers for using Creative Commons!

References:

Alliston, GW. 1975. Web-tagging ducklings in pipped eggs. The Journal of Wildlife Management. 39(3):625-628.

Krapu GL, Dwyer CP, Luna CR. 1991. Orphaned Mallard brood travels alone from nest to water. The Condor 93(3):779-781.

Just love this post! For the past few years I’ve watched a few Canada geese who have taken over eagle nests 100 feet up. Not surprisingly, I’ve never managed to be there when the babies jump out. Maybe some day! (Enjoyed the ducklings and the steps video – it’s like some sort of perverse video game.)

Thanks for the comment, I had no idea that geese sometimes nest high up too! I hope you do get to see them jump sometime. It looks from the videos I can find that the goslings all jump pretty quickly, so you’d need to have pretty excellent timing to see it.

As always, fascinating

You made ducklings seem new again! I loved reading this, you have a great style :)

Thanks!