The Joys of the Gaff Rig

By Duncan Blair

The bisquine “Cancalise” flying nine sails. From Working Sail, by Luke Powell, the Dorset Press, Ltd. U.K. 2012

I have been giving a lot of thought to the gaff rig lately, partly because I recently bent on a new gaff mainsail to my new gaff sloop and also because much of my writing involves gaff rigged boats of different sizes doing different things in different environments.

I am interested in luggers, especially the big, two-masted “bisquines” of Brittany, but I am an American living in Florida where luggers have always been rare and gaffers have mostly been forgotten.

I am not so much interested in the origins and evolution of the gaff rig as I am interested in it’s history of use over the past 200–300 years, as well as its continuing use.

Tom Cunliffe, author of Hand, Reef and Steer, writes that “deep-hulled gaffers and their sail plans are at the end of a line of natural development that stretches back to the time of Christ.”

Historical perspective is always valuable.

While I realize that Tom Cunliffe has several more decades of experience with gaffers than I do, I will respectfully point out that the United States has a rich history of shallow-hulled gaffers, including scows, sloops and schooners used for fishing, oystering and hauling a wide variety of cargoes, including illegal booze during Prohibition. This wide spectrum of hull types shows just how adaptable to different circumstances and environments the gaff rig is; English Channel to the Gulf of Mexico, the Dogger Bank to the Grand Banks.

Here is a list, not intended to be exhaustive, of the characteristics that I find to be important in gaffers. None of them are unique to gaffers—what I find to be of interest is that so many of them are found in gaffers.

1. STRENGTH

Gaffers typically have masts that are shorter than modern, bermuda rigged boats. The masts are often solid wood and are heavily stayed. Apart from the beautiful but extreme gaff rigged racing yachts of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, most gaffers do not look like radio antenna towers requiring a cat’s cradle of wire rope rigging to do their job.

I find the inherent strength of solid wood, properly stayed where necessary, to be both attractive and reliable.

I also like the running backstays; the “Sticks and String” approach encourages situational awareness.

Having used them, I do not care for Highfield Levers.

2. BEAUTY

Beauty is almost always subjective, some people even seem to like reverse sheer lines.

In 2017 my wife and I were in Maine aboard a schooner in the Gulf of Maine, where we had a nearly spiritual encounter with a Herreshoff New York 30, a classic gaff sloop. When we first saw her we were at anchor and she was about a quarter of a mile away from us, upwind. She looked like a knife in the water, except for her very large mainsail. We watched as she dropped her foresail and came down toward us, headed for the anchorage full of boats moored to buoys. As she came closer we could read the number on her sail: NY2.

The captain of our schooner jerked out his I phone and began searching for her history. She quietly, gracefully, sailed down closer to us, then snaked through the field of buoys and moored boats like a Sunfish, then scandalized her peak as one person strolled forward from the cockpit.

The way came off of her, she just “kissed” her mooring buoy and she was secured. Presto! It was one of the most beautiful pieces of boat handling I have ever seen.

NEW YORK 30. Sail area 984 sq. ft. 30 feet on the waterline, 43 feet overall. classicyachtinfo.com

Designed by Nathaniel Herreshoff for the New York Yacht Club in 1905. Only 18 NY30s were built and only by the Herreshoff, coming out of his yard at the rate of one finished hull per week. I have read that 12 of them are still in service, re-built but just as beautiful. I believe that the price in 1905 was $14,000. There is one for sale today on the Internet for $390,000.

I am, emphatically, not a yachtsman, but the beauty, grace, agility and proportion of the NY30, especially her gaff mainsail, are awesome. Very few gaffers are as beautiful as the NY30, which, because she was a yacht, really did not have to “work for her living”.

But almost every gaffer, however old, beat-up or home made, exhibits the sensuous curves of her gaff sail, especially when the wind is on her quarter. Looking aloft, from wherever you are on deck, you are presented with a curvaceous spread of canvas, in multiple planes, the curves accented by the straight lines of the gaff, gaff span and peak halyard and accented as well by the vertical seams of the sail running parallel to the leech.

All of this is framed by the sky and possibly a burgee; hopefully a flag of Scotland, possibly a flag of Cornwall.

Bristol Channel Pilot Cutter EZRA, on the West Coast of Scotland. From Working Sail, by Luke Powell

3. POWER

Tom Cunliffe writes that “it would take considerable engine power to drive a 50 foot Bristol Channel Pilot Cutter at the 9 knots she can reach with her sails under ideal conditions.”

The shorter, heavy masts and stays mentioned above enable gaffers to spread a large sail from an easily supported mast. The relative shortness of the gaffer mast, compared to the modern high aspect ratio bermuda rig causes less strain to be transmitted to the gaffer’s hull.

Best of all, the quadrilateral gaff sail carries more sail area up high than the modern bermuda rig. It is a known fact that the wind aloft is “cleaner,” has less turbulence, than the wind alow, which interfaces with the water’s surface.

The gaffer’s ability to utilize this clean wind is one of many reasons for its popularity as a work boat.

Bristol Channel Pilot Cutter TALLULAH, going like a freight train under working sail; 9.5–10 knots.

A lot of ink, possibly some blood and certainly a lot of beer has been spilled arguing that high aspect ratio, triangular sails can consistently drive vessels to windward at a higher angle than gaff rigged sails do, or can.

I do not dispute that, it is true beyond a doubt.

However, like many things in this world, it is not that simple. Here are some other relevant facts about the reality of pointing up to windward.

“Gaff sails are demonstrably more powerful once the wind is beyond 60 degrees from the bow.” Tom Cunliffe

To me, 60 degrees off the bow is a close reach.“Because of their low aspect gaffers are less prone to “stalling” i.e., falling into irons, if oversheeted, than something taller and narrower.” Tom Cunliffe.

It is not, or at least it should not, be the case that pointing high is the only criterion for windward performance.

As stated in #2 above, pointing high, if “over sheeted” is counter productive.

Gaffers point up at a lower angle, but can go faster than some high aspect ratio rigs, so when working to windward greater speed over the ground arguably compensates for pointing lower.

Remember also that a gaffer can rig a gaff vang to reduce mainsail twist, can fly a topsail and multiple headsails, including a jib topsail.

Two important points seldom addressed in the pointing up to windward controversy are:

The number of crew members required to trim and tack.

The question—Apart from racing around buoys, how much time and effort are normally spent beating to weather as compared to running, broad reaching, beam reaching and close reaching?

4. VERSATILITY

My recent efforts rigging our gaff sloop have made me even more aware of the straight forward approach and logic underlying traditional forms of rigging.

Everything is out in the open; blocks, belaying pins, rope that be easily spliced, steering with a simple, no mechanical linkage tiller bar, heavy loads lifted with multiple purchases, no winches and no winch handles, less deck clutter.

It is no more than personal opinion to say that I prefer this level of simplicity over the contemporary approach that is based on stainless steel gizmos (not really all that stainless), many of which are made in China and all of which are expensive if they are even available when you need them.

SOME EXAMPLES OF GAFF RIG SIMPLICITY.

Joshua Slocum’s circumnavigation of the planet, done over 100 years ago, was made on an elderly gaff rigged oyster sloop given to Slocum as a gift. Photos #5, 6 and 7 all refer to that sloop, called Spray. She was 39 feet, 6 inches overall; 14 feet, 2 inches in beam; with a draft of 4 feet, 2 inches.

Spray hauled out in Devonport, Tasmania 1897. Note her hull depth and generous beam. From A Man For All Oceans by Stan Grayson, Tilbury House Publications, 2017

Spray in the harbour of Sydney, Australia, sailing with a flowing sheet; this is often described a “the most iconic” of Spray photos. From A Man For All Oceans

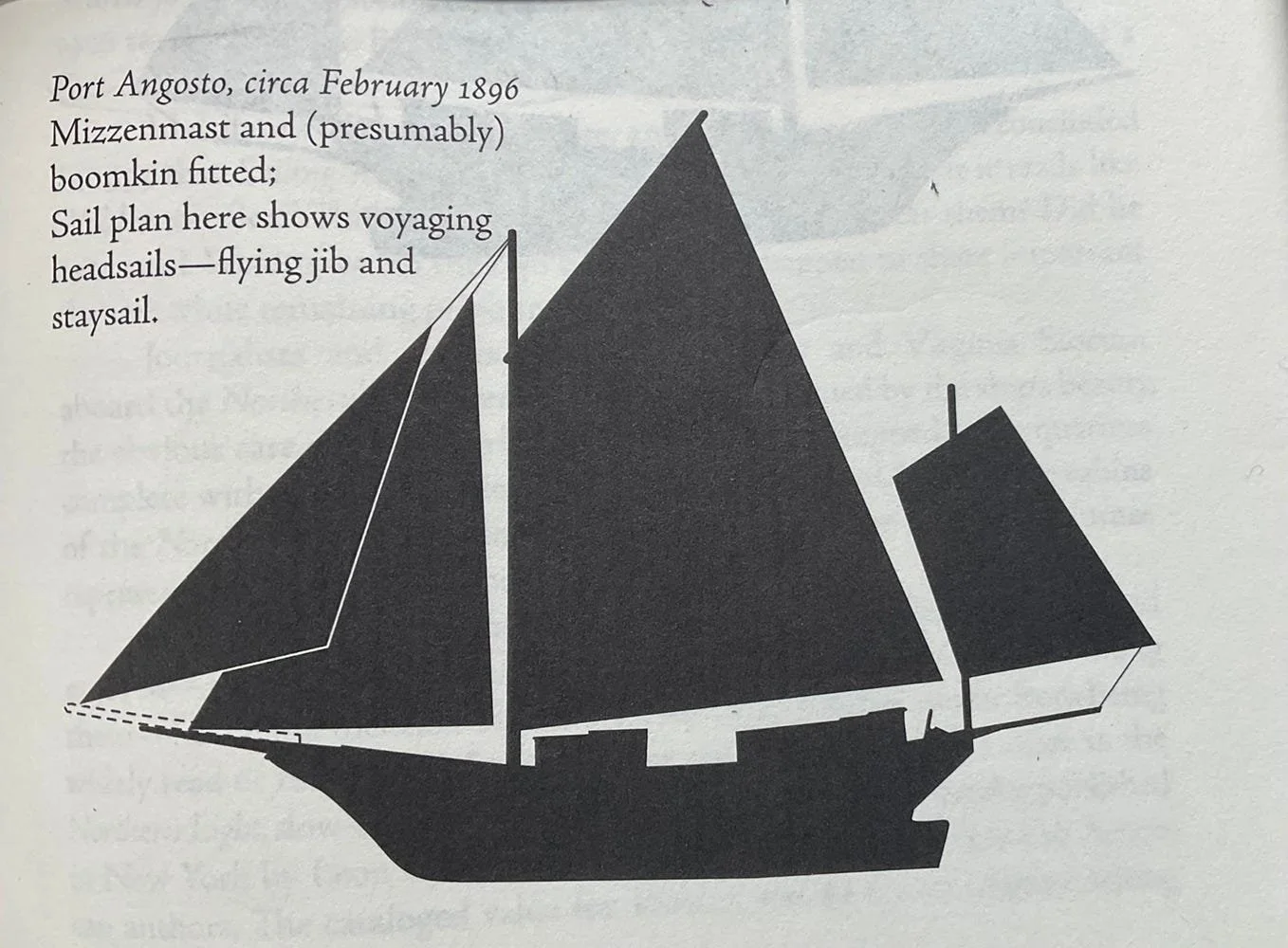

Spray’s final sail plan, one of many, showing the lug sail mizzen (jigger) added by Slocum in Port Angosto, Chile. From A Man For All Oceans

Because Spray came to Slocum as an oyster sloop she had a main sail with an area of over 700 square feet, necessary to pull the oyster dredge. A mainsail this big required the boom to extend out over Spray’s transom. After deciding to add the lug sail jigger Slocum took a handsaw and cut off the end of the boom so as not to hit the new mizzen, which was “a hardy young spruce, discovered on the beach.” This resulted in the mainsail area being reduced to an area of 604 square feet.

The addition of a lug sail mizzen was interesting, possibly the result of Slocum’s life experience in working sail; something useful, powerful, easily repaired or replaced.

A final point to be made about the versatility of the gaff rig is its ability to allow you to “take your foot off the gas”, without loosing forward motion, by scandalizing the peak. (This is what we saw the NY30 do in Maine.)

Scandalizing is the term used to describe loosening the peak halyard enough to drop the gaff to the horizontal, thereby reducing some, but not all, of the power of the sail. This is practical—when you understand what needs to be done—and easy to do, but it is not even an option for high aspect ratio rigs.

Terrapin Schooner design by Reuel Parker—a turtle fisherman’s workboat adapted as a yacht. Built about 20 years ago, with a Bateau type hull made of laminated, cold-moulded plywood, with an epoxy/fabric top layer. Topsides and deck 5/8 inch plywood. 34 feet overall, 10 feet of beam, 2 feet, 3 inches draft. Sail area 600 square feet, spars are solid Douglas fir. Photo shows run of the hull, centerboard and rudder.

TOMFOOLERY, the Terrapin schooner “sailing with a flowing sheet.”

This image says it all!

PAU

As always, all ideas and opinions stated above are mine alone.

Duncan Blair

Duncan Blair’s Traditional Sail Website can be found HERE