Listen to What Next:

Suzy Hansen loves Election Day in Turkey. “The amazing thing about Turkish Election Day is that it’s really like a jubilee. People love to vote here,” Hansen said. She lives in and reports from Istanbul. I spoke with her on Monday, the day after Turks went to the polls. The turnout was a stunning 92 percent. “It was incredible.”

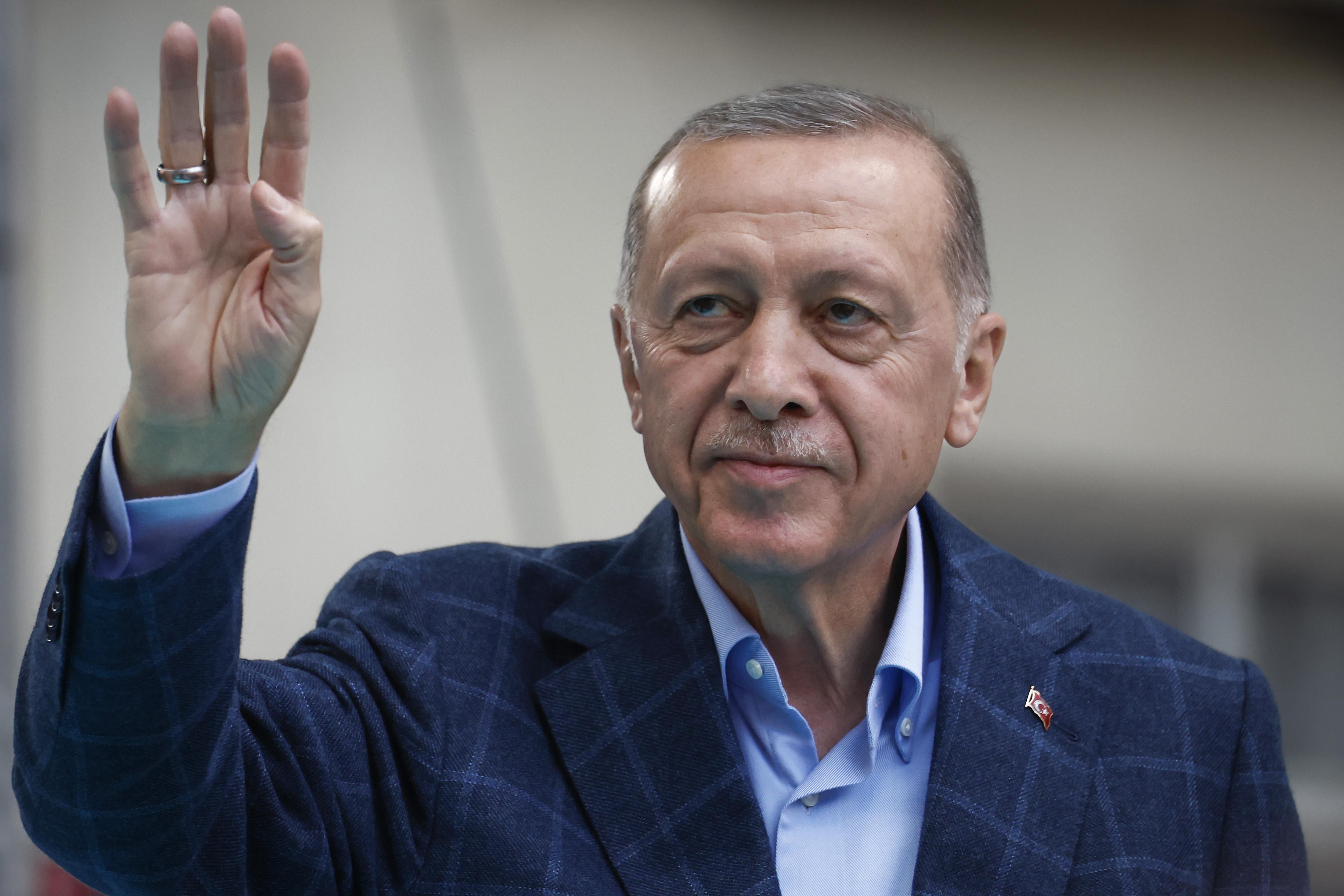

All 600 members of Parliament were on the ballot this weekend, but this election was mostly seen as a referendum on one man: Turkey’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan. He’s been in power one way or another for two decades. “It wasn’t clear this time what was going to happen. Turkey is experiencing a massive economic crisis. All you hear about from people is how much they are suffering,” Hansen said.

She watched results come in from a neighborhood that has historically been a stronghold for Erdogan. But while she’d hoped for some kind of decisive result, she didn’t get it. “People felt as if this could be a really stunning election defeat of Erdogan. And that’s not what happened.” Now, a runoff looms in just a couple of weeks. And Hansen knows that in a situation like this one—with limited time and lots of uncertainty—to some, Erdogan will feel familiar, safe. “This man has been in power since 2003. He controls all of the media. He controls all of the state institutions. Everybody here knows he’s going to most likely win that runoff.”

On Tuesday’s episode of What Next, I spoke with Hansen about how Recep Tayyip Erdogan became a seemingly unstoppable force. Our conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Mary Harris: Recep Tayyip Erdogan has been president or prime minister of Turkey since 2003, which is a long time. So I’m wondering if we can start out by explaining who he is and how he amassed so much power in the first place. He was mayor of Istanbul in the ‘90s, right? What kind of leader was he then?

Suzy Hansen: When Erdogan became mayor, it was also a shock. In Turkey, most of the political parties showed a conservative but centrist and secular line, and very religious Muslims were usually shut out. Now, that doesn’t mean that some of the political parties were not conservative, that people did not pray, but explicitly Islamist parties did not usually gain a lot of power. And Erdogan, who grew up in a poor neighborhood to religious parents—they were migrants from the Black Sea—joined these political parties that were basically the Islamist parties. And he came up through these political networks that he had been forming over the decades. So, from the bottom up, like a community organizer, he started amassing power, and he empowered even religious women in these neighborhoods. And they came out for him.

So, then he becomes mayor in 1994. And the thing is, the Islamists had been threatened by military coups, by the secularist state for a decent amount of time at that point. What he did was he said, “OK, I have this huge disadvantage, but I’m going to work really hard.” And he did. He cleaned up the city; he improved the social services. He was actually making things better in terms of actual real life. And a lot of the other political parties, the ones that had been in power and grown a little bit lazy, they hadn’t been providing for the poor. They hadn’t been improving people’s lives. And Erdogan got to work. And many people started to believe, OK, this guy, he’s doing something for us. Even people who might not vote for him could recognize that he was doing a good job.

The largely secular Turkish state was still suspicious of Erdogan, though. After he gave a fiery speech some claimed incited hate, he was sent to jail. It was part of an anti-Islamist crackdown in the country. But then: There was an earthquake. This was back in 1999.

When the earthquake happened in February, everyone who knows Turkey woke up thinking about the 1999 earthquake, and the fact that that had helped bring Erdogan to power. And now it was possible that an earthquake would bring him out of power, because in 1999 there was a massive earthquake. It was in the Marmara Region, which is where Istanbul is, and 17,000 people died. Because it was such a proof of failure that the country had not prepared its buildings for earthquakes, which they should have been doing, it discredited a lot of political parties at the time. They were seen as a failure. And soon after that, there was a massive financial crisis, which definitely was because of the corruption in political parties and the mismanagement of the economy. So, all of a sudden Erdogan gets out of jail and these two things are happening. And he comes back with a new political strategy. And that strategy is to form a political party that is not Islamist. It’s pro-EU, it’s pro-democracy, it’s pro–human rights, it’s kind of pro-Western, it’s pro-business—this being the most important thing—and people started getting excited. They said, “We’re going to clean up the country. We’re going to get rid of the mafias and the corruption, and we’re going to change this country for the better.”

It’s important to note how popular Erdogan initially was with the West. You laid out some of the reasons right there, which is he’s very pro-business. He sounds like a Western leader when you’re talking about making things more open economically like that.

This is the early 2000s. This is when privatization, when neoliberal policies were in vogue. And a country like Turkey was seen as one that was poor and corrupt and just needed to get with the global marketplace. And so Erdogan pledged to privatize the state companies, privatize the water company, privatize the electric company, and to make Turkey friendlier to Western markets.

How did that work out for the people of Turkey, all this rapid privatization?

In the beginning he was improving the economy. He was improving people’s lives. He was lifting people out of poverty. All of this money was flowing into Turkey as a great investment place. We saw museums going up and buildings being renovated. There were a lot of improvements. But in the background, and this is the key, the corruption was already starting, particularly in the construction industry.

Wasn’t that exactly what Erdogan said he was going to clean up?

Yes. But a leader like Erdogan, who knew he was under threat from the secular state who hated him, needed to amass his own wealthy business class

He needed friends, fast.

Yes, exactly. And he did this primarily through privatization bids, by giving all of these state contracts to his own businessmen and through building tons of apartment buildings. And he gave a lot of that development also to his own cronies.

If the first 10 years of Erdogan’s rule were about making Turkey into a neoliberal dream, the next 10 were about consolidating power, by any means necessary. In 2013, protests from outside of Erdogan’s party—and dissent from within—caused him to crack down on any whiff of opposition. And just three years after that, Erdogan put down a military coup. Hansen was living in Turkey during that coup; she says, it was terrifying.

They would release these announcements on the official gazette of the government on the internet at midnight. It would just be lists of people who were being purged from their jobs, whether in the state or at universities. You never had any idea what was going to happen to anyone, any day. The repression was really at a new level.

What do you attribute Erdogan’s longevity to, given all of this? Clearly he threatened the population. He expelled people who disagreed with him. Why has he lasted as long as he has?

Erdogan managed to create this wealthy business class that was profiting so much off of his rule. He was also able to take those kickbacks and those bribes and create this incredible party machinery. And he was able to give jobs to the poor and distribute money through these religious charity networks. So what you have then is such a stable of devoted voters. It’s not just about the ideology. It’s not just about religion, or because they saw Erdogan as a hero, although he is a charismatic hero. We have to keep in mind they were benefiting greatly financially from this man’s power. At that point, repression of the people who do not benefit from this power and who are opposing him becomes somewhat easy, because the people who are benefiting—it’s as if they didn’t mind.

As he also started facing threats from within and threats from without, he became more and more paranoid. I don’t think that we can underestimate the role of paranoia for a man like him, because he was never supposed to become this powerful in this country. A man like him never had that chance. He was kind of this trailblazer. And he always feared that he was going to be thrown out.

There had always been this residual sympathy for Erdogan because he was such an underdog. And the West was sympathetic to him for a very long time. But at this point, the state of this country is his creation. And what happened during the earthquake, what has happened with this economy and many other things are because of Erdogan’s vengefulness and cruelty.

If there was ever a time Erdogan would lose power, it would be now. Turkey has been dealing with crisis after crisis. Earlier this year, the country suffered two massive earthquakes, one after another. Tens of thousands—maybe even hundreds of thousands—of people died. And Erdogan’s government fumbled the response—badly.

They were very disorganized. They did not deploy the Turkish military. That would have been the most capable organization that could have immediately deployed people to these places and were trained in search and rescue. They failed to coordinate search and rescue within their own state organizations and with foreign rescue teams that were flying in at the drop of a hat. In some parts of the country, people were left alone for 48 hours. And in an earthquake, you have to get there immediately.

But Erdogan had centralized power around his own office, which means other offices could not work independently. They were waiting for a word from the president’s office first. What he saw happened was anger and fury and desperation on Twitter. I can’t look at the tweets from that time now without almost having a PTSD reaction because it’s so awful. It was all tweets from people either in the rubble or outside of the rubble who were saying, like, “Where is the state?” “My whole family is under the rubble.” “It’s a mother and her three kids and this and that. And they’re inside, and they’re screaming, and nobody can get to them.” It was so, so awful what these people went through. And it’s snowing in the north and it’s raining in the south. And Erdogan realized what a disaster this was. And he gave this really angry speech where he said, “Those of you who are spreading lies on social media, we’re going to write down your names and we will take care of you later.”

And then they shut down Twitter for, I think, 12 hours.

Do you think Erdogan now recognizes any part of the government response to the earthquake was a misstep?

They issued some apologies, but honestly, they were awful in those first weeks. They were defiant. They didn’t look very sympathetic. They were immediately releasing these crazy propaganda videos of bulldozers, basically implying they’re going to rebuild. I mean, people were still under the rubble. No one resigned. Some of their own people suffered, obviously, but I didn’t see sympathy.

On top of the earthquake, Erdogan has also been wrestling with crushing inflation and an economic nosedive. And everyone is talking about it.

Every single young man I spoke to, whether in a taxi or in a shop—all of them were talking about how they can’t survive financially. And I really mean that when I say that. I’m not talking about like, Oh, things are bad. I mean, they can afford to get married. They can’t afford to buy meat. I heard so many men talking about wanting to save all their money for a flight to Mexico and then go across the American border. You don’t hear Turks talk like this.

These are the exact circumstances that brought Erdogan to power, a financial crisis and an earthquake.

Absolutely. But here’s the difference: The opposition parties don’t necessarily have the track record of improving an economic situation and improving people’s lives. So, you still have people thinking, Well, Erdogan fixed this place once. It’s probably only him who can do it again.

Erdogan’s opposition has made a real effort to reach the Turkish people and change their minds. The president’s main political rival is an economist named Kemal Kilicdaroglu. During the campaign, he’d tweet out these videos of himself at a kitchen table, complaining about the high cost of onions, a staple of the Turkish diet. In the end, six opposition parties all threw their weight behind him Kilicdaroglu.

That doesn’t happen. And also, the Kurds were mostly behind that collection of parties, and many of them are conservative or right-wing nationalists. But they couldn’t necessarily maybe coalesce around the opposition candidate, Kemal Kilicdaroglu, who hasn’t really been as successful in elections in the past and was seen as some people as a weak leader and who is also a member of a Muslim minority sect.

The opposition, they had been doing pretty well these last weeks, but Sunday night they really didn’t get ahead of things and show strength. So, people are feeling pretty demoralized about them. Of course, we’re still in the midst of this. We’re still processing it. So who knows what will happen. But I don’t hear a lot of very optimistic people.

You seem pretty certain that Erdogan’s going to win this runoff. Can you explain why?

Well, first of all, because that’s what all of the Turkish people are saying, and I always defer to them. But I would say even though he lost votes, he did do better than he and his party expected. A lot of voters who might have been undecided or who voted for the third-party candidate might look at the situation right now and say, “Look, Erdogan’s party maintained the power in the Parliament. That’s a sign that power is behind him. The wind is at his back.” And when it comes down to Erdogan and Kilicdaroglu, people are going to say to themselves, “Well, we don’t actually know how this coalition is going to govern. And we do know these things about this man. Yeah, maybe he’s made some mistakes, as they say, but probably only he, both domestically and on the world stage, is strong enough to fix it.”

And my understanding is that a small but significant percentage of the electorate cast their ballot for another person who ran who was actually more conservative than Erdogan. And that might influence what happens next, too. Those people wouldn’t be voters who would necessarily go with someone who is a more liberal candidate.

Well, what they are is right-wing nationalists. It’s very anti-Kurdish. It has mafia connections. That’s the party that this man, Sinan Ogan, comes from. And he uses the most virulent anti-Syrian rhetoric. His demand is that all refugees are sent away. He’s also talking very tough about the Kurds. It’s unclear right now if he’s really the kingmaker. I always kind of think that the only kingmaker is the king. But some people are speculating about where his 5 percent of the vote will go. Will he signal to his voters in one direction or another? But most of us assume they’re going to go to Erdogan right now.

I feel like Erdogan is like a cat. He’s got nine lives. There’s been a coup attempt. He’s been jailed. The international community is not thrilled with him right now because he’s making moves at NATO, trying to get concessions for stuff like letting Finland in. I can see why it’s hard for you to think anything’s going to change with the upcoming runoff.

Look, what Erdogan has managed to do on the international stage is pretty fascinating. He’s both on the side of Ukraine. He’s on the side of Russia. But frankly, every country in this region plays a two face. The people who aren’t used to that are the Americans, who are like, “You’re either with us or you’re against us.” But at the same time, Turkey is a NATO country. The Americans need them to a certain degree. The Russians need Turkey. Everybody needs him a little bit.

Subscribe to What Next on Apple Podcasts

Get more news from Mary Harris every weekday.

So in the next two weeks, with this runoff looming, what are the stories you want to tell?

Honestly, I don’t know right now because I’ve been covering this country for 15 years. We have a financial crisis. We had a devastating, devastating earthquake. We’ve had years of repression. And he’s still coming out on top. More work is probably needed to be done, as it always was, in the communities who actually vote for him and who actually still love him. And also the ones who claim that they’re not voting for him but actually are. To some degree, what I think has been misunderstood is the extent of how much his voters favor him, but also maybe the extent to which Turkish voters are right wing. I don’t know the answer to that.

It’s just people got hopeful, that’s all.

Do you think they’re still hopeful?

Not today. No.