In this essay, Veronika Molnar writes about the Hungarian Roma artist Omara (1945-2020) whose diverse practice challenged the status quo of Hungary’s contemporary art scene. The essay also highlights the importance of the RomaMoMA project, which offers a transnational approach to presenting and contextualizing the works of Roma artists inside and outside the framework of established art organizations.

I paint the story of my life and my opinion about the world

If you frown: do it after me . . .

But your eye be removed as well—and you be a gypsy . . .

Be deeply humiliated everywhere you go from childhood to this day

Otherwise, I’m not interested in your opinion . . .

—Omara, “If you have taken the time to see Omara’s scribbles,” 2011

It took a simple gesture for Omara (Oláh Mara, 1945–2020) to transcend the category of “naive gypsy painter,” as she liked to call herself, and become an internationally recognized contemporary artist: handing over her glass eye to Hungarian American businessman and philanthropist George Soros at the opening of the First Roma Pavilion at the 52nd Venice Biennial in 2007. Or at least, that is the moment that curator and art historian Tímea Junghaus has deemed pivotal in reframing Omara’s artistic practice, in which “actions, media presence, and performances” became an integral part.1Tímea Junghaus, “Az egyszemlátó Omara ékszerei” (“The Jewelry of One-Eyed Omara”), exindex, November 6, 2011, https://exindex.hu/flex/az-egyszemlato-omara-ekszerei/. During her lifetime, Omara relentlessly worked on carving out space for herself and other Roma artists in contemporary art institutions, which have historically refused to represent the voices of the Roma, even though the Roma are the biggest ethnic minority in Europe. Omara fought for artistic agency through painting, public appearances, and actions both inside and outside of art institutions—from exhibiting her work in a Hungarian prison2Omara, “Omara, Oláh Mara börtönben kiállít és beszél,” Omara addressing the inmates of the prison in Tököl, posted April 27, 2017, YouTube video, 5:19, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y0LsksLMZUA. to creating the first Roma gallery in 1993 in her apartment.3“Életrajz” (“Biography”), Omara’s website, http://www.omara.hu/eletrajz.html. Her works were recently presented at Documenta 15 in Kassel, Germany, by RomaMoMA—a transnational, collaborative project of OFF-Biennále Budapest and the European Roma Institute for Arts and Culture (ERIAC).

“Hungary—the—Gypsy—woman—at the—Venice—Biennale—2007.VI.7. Mara on the Lido of Venice. Now—you can—mock—me—whether—I’m—a—painter—or—not?—Omara”

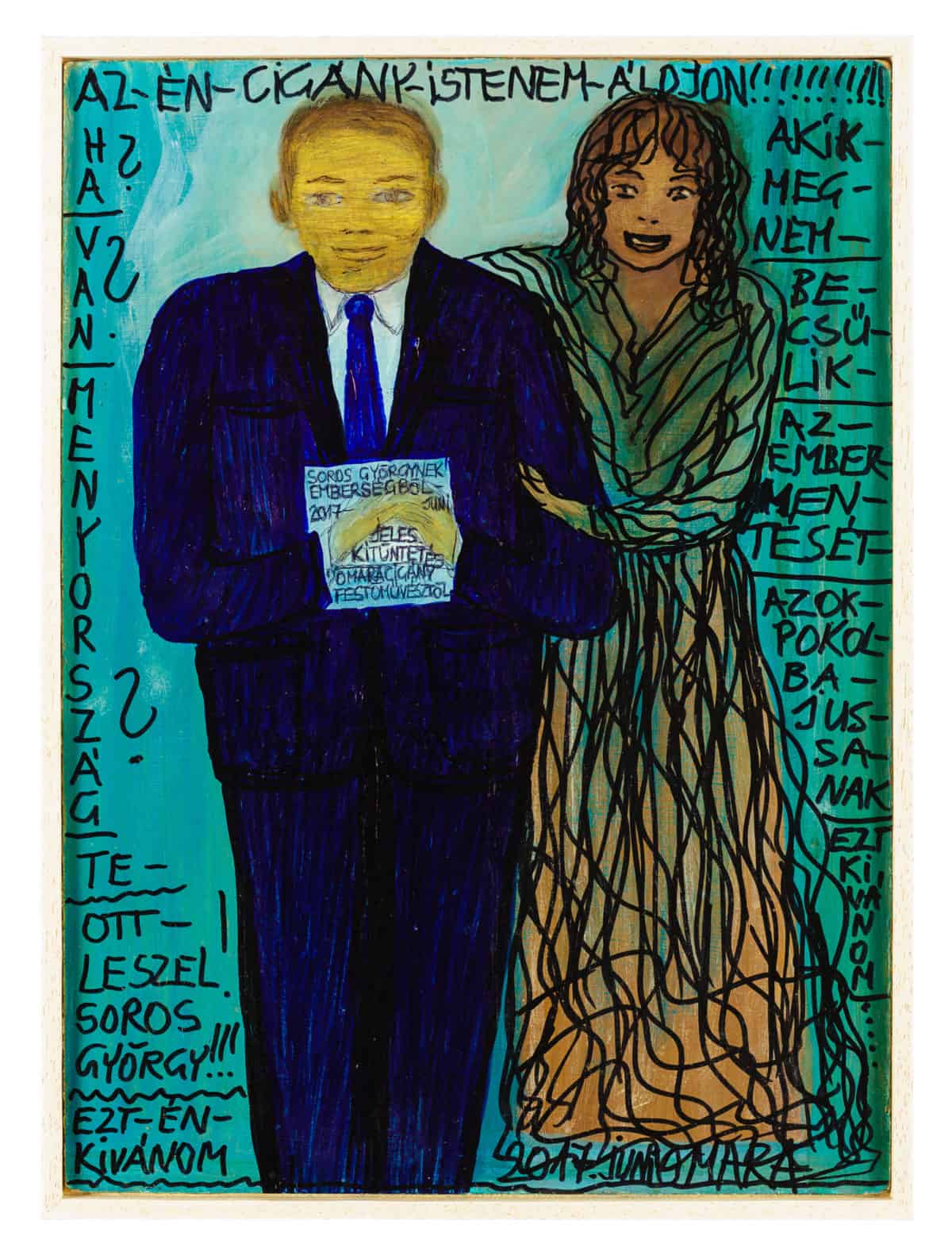

“May—my—Gypsy—God—bless you!!!!!!!!!!!

If? there is? a heaven?

You will be there! George Soros!!!

This is what I wish.

Those who don’t appreciate that he saved people, should go to hell

I wish. . . . .

To George Soros for his humanity

June 2017

Distinguished Service Award

Gypsy painter Omara”

Born to a Roma family in Monor, Hungary, and raised in humble economic circumstances, Omara married a “peasant”—as she referred to non-Roma Hungarians4Tímea Junghaus has pointed out that Omara objectified non-Roma whites in her paintings and writings in the same way that the majority society has objectified the Roma. Tímea Junghaus, “Az ‘episztemikus engedetlenség.’ Omara Kék sorozatának dekolonializált olvasata” (“‘Epistemic Disobedience.’ A Decolonial Reading of Omara’s Blue Series,” Ars Hungarica 39, no. 3 (2013): 302–17, which is the most comprehensive theoretical analysis of the artist’s work to date.—and juggled raising their daughter with demanding jobs, including often working as a cleaning lady. She only began making art in 1988, at the age of forty-three, when she was suffering from a migraine: she drew a portrait of Sophia Loren, and by the time it was completed, her pain was gone.5Omara, Mara festőművész (Painter Omara) (self-pub., Szolnok: Repro Stúdió, 1997), 39. Realizing the healing potential of art-making, Omara began to paint episodes from her life, including her childhood memories and traumas. As a Romani woman and multiple cancer survivor, her firsthand experiences of dispossession, sexism, anti-Gypsyism, police violence, and neglect within the healthcare and education systems became the subjects of many of her paintings. In the beginning, she was humiliated for her artistic endeavors, even by family members, but her career quickly took a turn.

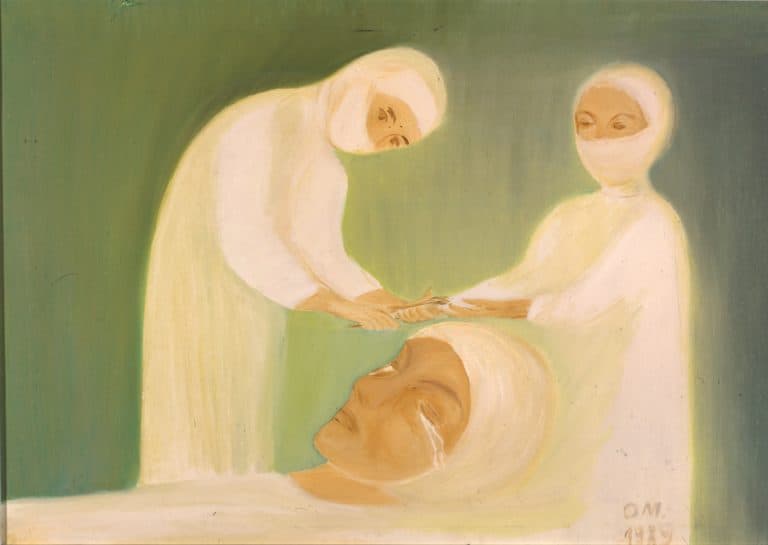

Omara always had an ambiguous relationship with art institutions: from early on, she had good instinct in terms of navigating their power structures but nonetheless played by her own rules, which were often seen as eccentric or even scandalous. In 1991, at the beginning of her career, she brought a painting depicting her eye surgery to the Hungarian National Gallery for evaluation. According to the artist, the director himself encouraged her to continue working.6Extrém egyéniség fest a luxusputriban (An Extreme Individual Painting in the Luxury Hut), Index, posted April 24, 2011, Index video, 11:18, https://index.hu/video/2011/04/24/omara/. The following year, an incident at one of her early exhibitions in Szeged, Hungary, inspired a complete shift in her approach to painting and exhibiting work. A self-portrait depicting the artist on all fours, looking for her glass eye in the grass after a relative’s funeral—a real occurrence—was mistakenly titled “Mara Resting,” while a double portrait of Omara and her sister was mislabeled “Lesbians.” When the artist found out what the latter title meant, she was outraged and painted a picture of lesbians as a gift to the curator.7Junghaus, “Episztemikus engedetlenség,” 307. After this episode, she began to inscribe her paintings with text to avoid misinterpretation.8Ibid.

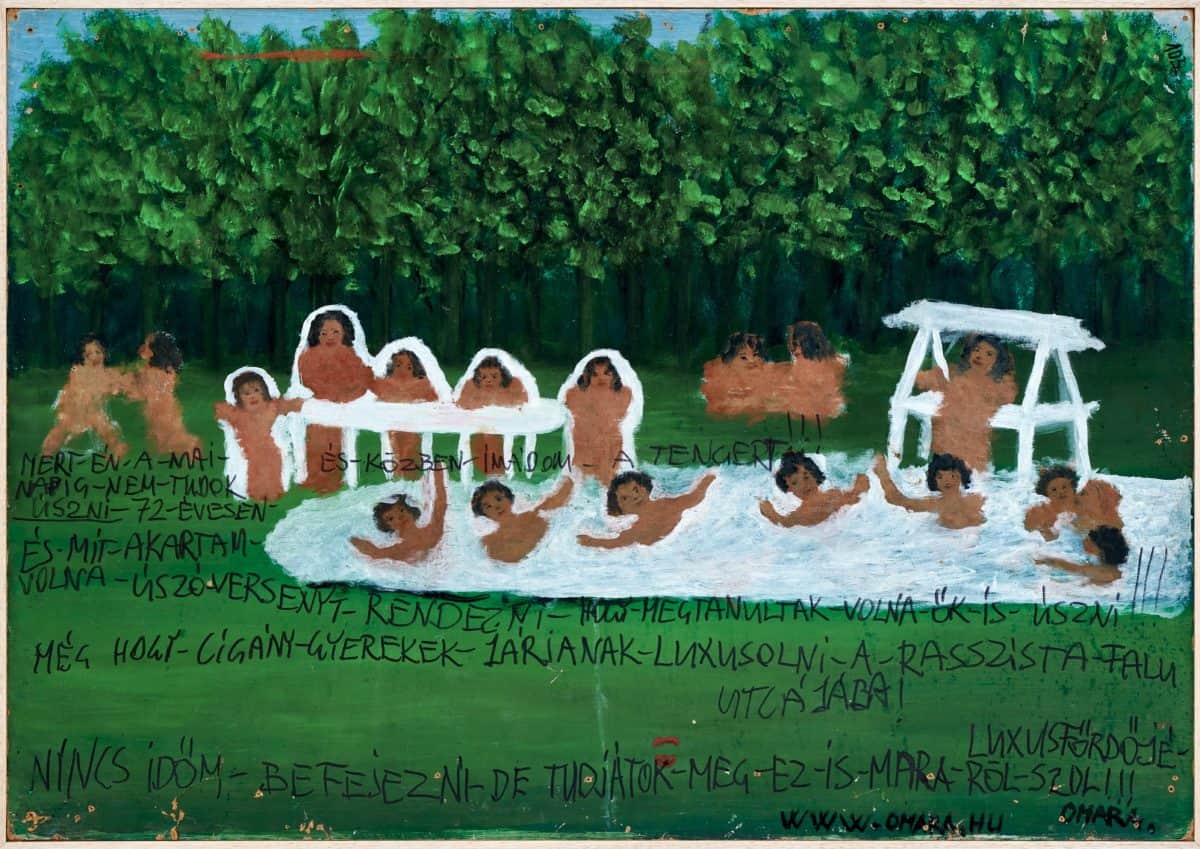

Her inscriptions, which she feverishly scribbled onto the surface of the paintings, often fill all the space around the protagonists in her flat, stylized compositions, sometimes even running over them. One sentence cuts into another, breaking the rules of grammar and linearity, forcing viewers to puzzle over the words and images as they attempt to follow the artist’s tempo and logic. Reconstructing language as a way to reflect her own unique voice, experience, and frustrations is in itself an act of defiance, but many of her exclamations are not only narrative, but also performative: if readers are willing to engage with the text, they might be blessed, cursed, or given instructions—for example, from “May—my—Gypsy—God—bless you!!!!!!!!!!” to “Think whatever you want!” Moreover, these exclamations were often extended into physical space and time. During exhibition openings, television interviews, and video performances,9Out of the many occasions when Omara “performed” for the camera, the best known is the twenty-six-minute-long portrait video taken by fellow artist János Sugár in 2009. the artist frequently read them out loud, laughing, emphasizing, and adding further context and comments to her statements.

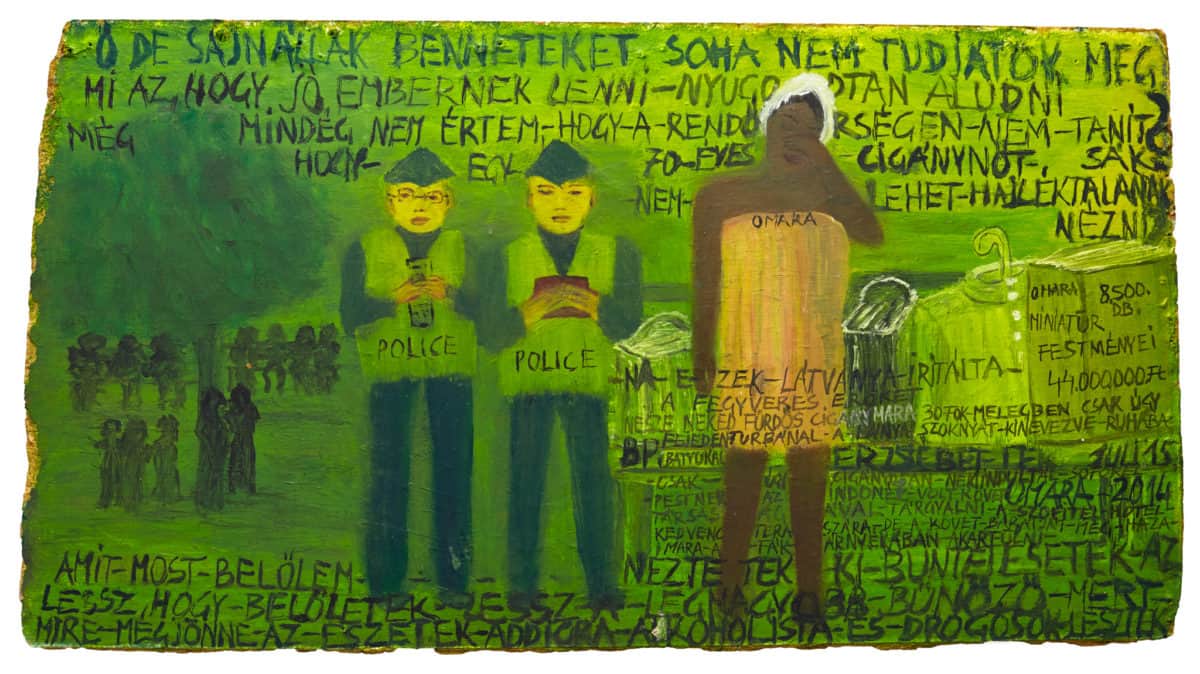

Woven into personal narratives, Omara’s paintings frequently comment on political events and criticize the systemic discrimination in Hungary against the Roma by the police, politicians, and others. One of her late paintings depicts the artist with two policemen, and the inscription reads: “Oh, but I pity you. You will never know what it is to be a good person—to sleep soundly. I still don’t understand why it—is—not—taught—to—the—police—that—a—70-year-old—Gypsy—woman—can’t—be—labeled—as—homeless?” In the text, Omara further describes how she was on her way to a hotel in Budapest, wearing a turban, to meet with the former Indonesian ambassador when the police stopped her to ask for her ID. In a short interview video, she adds, “If they knew I’m making money off of them, they wouldn’t fucking humiliate me.” In another example, “The peasant can drink in the pub from the social aid?. . .,” Omara calls out the mayor of Monok, whose legislation restricted how its residents could spend their government assistance: “Tell the mayor of Monok that my pension is 28,000 Ft [70 USD], he can tell his mother how to spend her pension but not the gypsy.” In an act of defiance, the artist painted herself and her daughter in the lush garden of her “luxury shack,” where both Omara and her animals are depicted smoking, as anyone receiving assistance was not allowed to buy cigarettes with it.

benneteket soha nem tudjátok meg mi az hogy jó embernek lenni . . .”). 2014. Oil on fiberboard, 12 13/16 x 23 5/8 in. (32.5 x 60 cm). Courtesy Everybody Needs Art and Longtermhandstand, Budapest

“Oh, but I pity you. You will never know what it is to be a good person—to sleep soundly.

I still don’t understand why—it—is—not—taught—to—the—police—that—a—70-year-old—Gypsy—woman—can’t—be—labeled—as—homeless?

Omara’s miniature paintings: 8500 pieces, 44,000,000 HUF

So—the —sight—of—these—irritated—the—armed—forces

Take—this—‘bathlady’ Mara—in —30-degree—heat—with —a—turban—over—your—head—in —a—dress—made—out—of—your—daughter’s—skirt—with —bags—in—your hands—just—like—a—Gypsy—you —drove—to—Pest—with—a—chauffeur

Erzsébet Square 2015 July

To—meet—the—former—Indonesian—ambassador—on—my—favorite—terrace—of—the—Sofitel—Hotel.

The—friend—of—the—ambassador . . . Mara—wanted—to—sit—in—the—shadow—of—the—trees.

What—you—saw—in—me—now—will—be—your—punishment—that—you’ll—be—the—biggest—criminals—because—before—you—would—come—to—your—senses—you’ll —already—become—alcoholcs—and—drug—addicts.”

“Because to this day I can’t swim—at the age of 72—and I love the sea!!! And what would I have wanted—but to organize a swimming competition—so that they would have learned to swim!!!

No way that Gypsy children go to the street of this racist village to get some lux! I have no time to finish—but you should know this is also about Mara’s luxury bath!!! www.omara.hu Omara”

For more than two decades, Omara’s artistic practice was understood only in the context of her paintings, yet to fully comprehend the artist’s significance, it is crucial to analyze her interventions, media appearances, and public exposures—which might be referred to as performances, although I prefer to use the term “enactments.” Following Andrea Fraser, using this term allows us to “look past the specifically and narrowly defined artistic motives and meanings of what we do, framed by art discourse above all . . . and begin to take into account the full range of motives and meanings of our activities.”10Andrea Fraser, “Performance or Enactment,” in Performing the Sentence: Research and Teaching in Performative Fine Arts, ed. Carola Dertnig and Felicitas Thun-Hohenstein(Berlin: Sternberg Press in association with Akademie der bildenden Künste Wien, 2014), 126. Omara never named, recorded, or framed these actions as works of art; indeed, many of them live on in the form of anecdotes and oral histories, or as video documentation by others. When viewed as integral to Omara’s body of work, they position the artist as a pioneer in bringing Roma resistance into the contemporary art institution.

Omara’s most cited and best-remembered enactment is her “I wasn’t invited scene,” in which she repeatedly interrupted art events and openings featuring her work. On these occasions, Omara made theatrical entrances to different institutions, and called out the organizers for failing to invite her to their event—whether or not this was actually the case—as Junghaus has recalled.11Junghaus, “Az egyszemlátó Omara ékszerei.” During one such intervention, analyzed in a roundtable by Tímea Junghaus and sociologist Éva Kovács, she interrupted a screening at the Kunsthalle in Budapest, appearing in a white dressing gown and white turban, causing a scene and accusing the organizers of leaving her out. Her interruptions could seem playful or hostile, depending on one’s awareness of her practice, but the timing, location, and outfit she wore were always strategically constructed. As Kovács has pointed out, Omara utilized these actions to carve out institutional spaces where she could stand.12Romakép Műhely—Kortárs roma képzőművészet, roundtable discussion moderated by Andrea Pócsik, July 31, 2014, YouTube video, 1:29:19, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yGUaX8a7Ito. Junghaus called them “ritualized productions, which are shaped and repeated under and due to oppression, building on the power of prohibition and taboos, and fleeing the horror of exclusion.”13Junghaus, “Az egyszemlátó Omara ékszerei.” In her interventions, as well as in her media appearances, Omara enacted stereotypes projected onto her as a means of both provocation and self-protection.

A comparison between Omara’s interventions and the performances of conceptual artist and cultural critic Lorraine O’Grady’s14Like Omara, O’Grady also became an artist in her mid-forties. alter ego, Mlle Bourgeoise Noire (Miss Black Middle Class),15See Lorraine O’Grady (born 1934), Untitled (Mlle Bourgeoise Noire), 1980–83/2009, MoMALearning, https://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/lorraine-ogrady-untitled-mlle-bourgeoise-noire-1980-832009/. demonstrates how Romani women artists’ struggles within Central and Eastern European art institutions parallel those of Black women artists in the United States—albeit in a different period and under different sociopolitical circumstances16For scholarship on the ways Romani activism and feminism can be situated in postcolonial discourse—with a special focus on the Black Civil Rights movement in the United States—see the following non-exhaustive list of publications available in English: Angéla Kóczé and Nidhi Trehan, “Racism, (Neo)colonialism and Social Justice: The Struggle for the Soul of the Romani Movement in Postsocialist Europe,” in Racism Postcolonialism Europe, ed. Graham Huggan and Ian Law (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2009): 50–73; Angéla Kóczé et al.,eds., The Romani Women’s Movement: Struggles and Debates in Central and Eastern Europe (London: Routledge, 2019); and Anna Mirga-Kruszelnicka and Jekatyerina Dunajeva, Re-Thinking Roma Resistance Throughout History: Recounting Stories of Strength and Bravery (Budapest: ERIAC, 2020).—and sheds light on how Omara’s work might find its place in the art historical canon. Mlle Bourgeoise Noire made her debut in 1980 at an opening at Just Above Midtown, a New York avant-garde art space championing Black artists. Wearing an evening gown and cape assembled from 180 pairs of white gloves, she performed a disruptive action in which she whipped herself with cat-o’-nine tails (transformed from the chrysanthemums she handed out) and shouted poems of protest, one of which ended in “BLACK ART MUST TAKE MORE RISKS!!!” in criticism of Black artists she believed were catering to white audiences.17Stephanie Sparling Williams, “Mlle Bourgeoise Noire (1980–83),” in Lorraine O’Grady: Both/And, ed. Catherine Morris et al., exh. cat. (Brooklyn: Dancing Foxes Press in association with the Brooklyn Museum, 2021), 58. She formulated this “guerilla-theater intervention”18Siddhartha Mitter, “Lorraine O’Grady, Still Cutting Into the Culture,” New York Times, February 19, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/19/arts/design/lorraine-ogrady-brooklyn-museum-retrospective.html. as a response to the exhibition Afro-American Abstraction, which had opened earlier that year at the Institute for Art and Urban Resources (now MoMA PS1).19Williams, “Mlle Bourgeoise Noire (1980–83),” 58. As Zoé Whitley has pointed out, “With Mlle Bourgeoise Noire, O’Grady could, from a unique perspective, address both systemic exclusions in the art museum and prevailing assumptions of what comprised the so-called Black experience in many culturally specific art spaces.”20Zoé Whitley, “Mlle Bourgeoise Noire Throws Down the Whip: Alter Ego as Fierce Critic of Institutions,” in Lorraine O’Grady: Both/And, 49.

Through utilizing different cultural markers and voicing their demands loud and clear, both Omara and O’Grady disrupted the normative behaviors of art institutions, pointing out their pervasive whiteness, which was present in the 2000s in Hungary just as much as it was in the mid-1970s and 1980s in the United States.21While one of the first large-scale institutional survey exhibitions to present Black American Art, Two Centuries of Black American Art, took place in 1976 at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the first museum exhibition to situate Roma artists in a contemporary museum setting was only organized in 2004 in Hungary. Elhallgatott Holocaust (Hidden Holocaust) at the Műcsarnok/Kunsthalle in Budapest featured Omara’s works prominently. But while O’Grady’s work is finally receiving the attention it deserves,22O’Grady’s 2021 major retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum closed on July 18, 2021, and MoMA recently opened Just Above Midtown: Changing Spaces, a survey exhibition examining the history of Just Above Midtown, which includes works by the artist. The MoMA exhibition was organized in collaboration with the gallery’s founder, Linda Goode Bryant, and runs through February 18, 2023. Omara’s is not. In fact, her legacy has been more challenging to secure, even though the artist’s estate has become very active in showcasing her work both locally and internationally.23The artist’s estate, Everybody Needs Art/Longtermhandstand, has presented Omara’s work at international art fairs such as the Biennale Matter of Art 2022 and Artissima 2022, and at a solo exhibition held at UGM | Maribor Art Gallery in 2022. While Omara passed away two years ago, a major Hungarian or Eastern European institution has yet to step forward to hold a large-scale retrospective—the Ludwig Museum in Budapest could potentially initiate such an exhibition, as it owns eight paintings from Omara’s renowned blue series.24“Mara Oláh,” Ludwig Múzeum website, https://www.ludwigmuseum.hu/en/author/olah-mara.

In response to the question of how the works and legacies of outstanding Roma artists like Omara could be shepherded, RomaMoMA has offered a potential solution. Modeled after a “nomadic, flexible institutional operation,” RomaMoMA critically approaches questions such as how a “Roma Museum of Contemporary Art” could operate to collect, present, and preserve the works of artists of Roma origin, or how we could “think about the cultural representation of a people, of an ethnic minority, without a nation-state behind it?”25Marina Csikós et al., “Collectively Carried Out—Tamás Péli: Birth,” in On the Same Page, ed. Rita Kálmán et al. (Budapest: OFF-Biennále Budapest, 2022), 20. While RomaMoMA aims to fill a gap in institutional representation of Roma artists, it also challenges the principles and practices of museums built on modernism and aims to contribute to a paradigm shift by “decolonizing the way in which the museum speaks (or does not speak) on behalf of communities whose cultural assets—whether an object, an artefact, or a story—have been stored in warehouses or put on display in exhibition halls for centuries.”26Ibid. It is strategic about avoiding monographic presentations of artists27Nikolett Erőss, OFF-Biennále curator, phone conversation with author, August 2022. and follows a nomadic practice with pop-up exhibitions and events. Its latest exhibition, One Day We Shall Celebrate Again, presented at Documenta 15, featured Omara’s paintings and a twenty-six-minute-long video of the artist by János Sugár (Omara, 2010), among work by multiple generations of Roma artists.

While there is growing momentum and interest in exploring the work of Roma artists across Europe, with Documenta 15 being the latest example, it would not have been possible without RomaMoMA having paved the way to present their work in a transnational and collaborative way. Discussing the mission of RomaMoMA on the platform of MoMA begs the questions: In a future reality, will it be possible to close the gap between the two entities? Will brick-and-mortar institutions like MoMA28MoMA’s collection currently includes artworks representing the Roma—from the photographs of August Sander (1876–1964) to the paintings of Henri Rousseau (1844–1910) and Emil Nolde (1867–1956)—but it lacks works by Roma artists.—which is continuously reinventing its curatorial and acquisition strategies to become more inclusive—amplify the voices of Roma artists so that interventionist alternative projects will no longer be needed?

The second part of this article, “Disrupting the Institution through Language and Enactment: Omara’s Resistance, Part II,” which focuses exclusively on Omara’s enactments, has been published on the RomaMoMA blog by the author.

- 1Tímea Junghaus, “Az egyszemlátó Omara ékszerei” (“The Jewelry of One-Eyed Omara”), exindex, November 6, 2011, https://exindex.hu/flex/az-egyszemlato-omara-ekszerei/.

- 2Omara, “Omara, Oláh Mara börtönben kiállít és beszél,” Omara addressing the inmates of the prison in Tököl, posted April 27, 2017, YouTube video, 5:19, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y0LsksLMZUA.

- 3“Életrajz” (“Biography”), Omara’s website, http://www.omara.hu/eletrajz.html.

- 4Tímea Junghaus has pointed out that Omara objectified non-Roma whites in her paintings and writings in the same way that the majority society has objectified the Roma. Tímea Junghaus, “Az ‘episztemikus engedetlenség.’ Omara Kék sorozatának dekolonializált olvasata” (“‘Epistemic Disobedience.’ A Decolonial Reading of Omara’s Blue Series,” Ars Hungarica 39, no. 3 (2013): 302–17, which is the most comprehensive theoretical analysis of the artist’s work to date.

- 5Omara, Mara festőművész (Painter Omara) (self-pub., Szolnok: Repro Stúdió, 1997), 39.

- 6Extrém egyéniség fest a luxusputriban (An Extreme Individual Painting in the Luxury Hut), Index, posted April 24, 2011, Index video, 11:18, https://index.hu/video/2011/04/24/omara/.

- 7Junghaus, “Episztemikus engedetlenség,” 307.

- 8Ibid.

- 9Out of the many occasions when Omara “performed” for the camera, the best known is the twenty-six-minute-long portrait video taken by fellow artist János Sugár in 2009.

- 10Andrea Fraser, “Performance or Enactment,” in Performing the Sentence: Research and Teaching in Performative Fine Arts, ed. Carola Dertnig and Felicitas Thun-Hohenstein(Berlin: Sternberg Press in association with Akademie der bildenden Künste Wien, 2014), 126.

- 11Junghaus, “Az egyszemlátó Omara ékszerei.”

- 12Romakép Műhely—Kortárs roma képzőművészet, roundtable discussion moderated by Andrea Pócsik, July 31, 2014, YouTube video, 1:29:19, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yGUaX8a7Ito.

- 13Junghaus, “Az egyszemlátó Omara ékszerei.”

- 14Like Omara, O’Grady also became an artist in her mid-forties.

- 15See Lorraine O’Grady (born 1934), Untitled (Mlle Bourgeoise Noire), 1980–83/2009, MoMALearning, https://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/lorraine-ogrady-untitled-mlle-bourgeoise-noire-1980-832009/.

- 16For scholarship on the ways Romani activism and feminism can be situated in postcolonial discourse—with a special focus on the Black Civil Rights movement in the United States—see the following non-exhaustive list of publications available in English: Angéla Kóczé and Nidhi Trehan, “Racism, (Neo)colonialism and Social Justice: The Struggle for the Soul of the Romani Movement in Postsocialist Europe,” in Racism Postcolonialism Europe, ed. Graham Huggan and Ian Law (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2009): 50–73; Angéla Kóczé et al.,eds., The Romani Women’s Movement: Struggles and Debates in Central and Eastern Europe (London: Routledge, 2019); and Anna Mirga-Kruszelnicka and Jekatyerina Dunajeva, Re-Thinking Roma Resistance Throughout History: Recounting Stories of Strength and Bravery (Budapest: ERIAC, 2020).

- 17Stephanie Sparling Williams, “Mlle Bourgeoise Noire (1980–83),” in Lorraine O’Grady: Both/And, ed. Catherine Morris et al., exh. cat. (Brooklyn: Dancing Foxes Press in association with the Brooklyn Museum, 2021), 58.

- 18Siddhartha Mitter, “Lorraine O’Grady, Still Cutting Into the Culture,” New York Times, February 19, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/19/arts/design/lorraine-ogrady-brooklyn-museum-retrospective.html.

- 19Williams, “Mlle Bourgeoise Noire (1980–83),” 58.

- 20Zoé Whitley, “Mlle Bourgeoise Noire Throws Down the Whip: Alter Ego as Fierce Critic of Institutions,” in Lorraine O’Grady: Both/And, 49.

- 21While one of the first large-scale institutional survey exhibitions to present Black American Art, Two Centuries of Black American Art, took place in 1976 at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the first museum exhibition to situate Roma artists in a contemporary museum setting was only organized in 2004 in Hungary. Elhallgatott Holocaust (Hidden Holocaust) at the Műcsarnok/Kunsthalle in Budapest featured Omara’s works prominently.

- 22O’Grady’s 2021 major retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum closed on July 18, 2021, and MoMA recently opened Just Above Midtown: Changing Spaces, a survey exhibition examining the history of Just Above Midtown, which includes works by the artist. The MoMA exhibition was organized in collaboration with the gallery’s founder, Linda Goode Bryant, and runs through February 18, 2023.

- 23The artist’s estate, Everybody Needs Art/Longtermhandstand, has presented Omara’s work at international art fairs such as the Biennale Matter of Art 2022 and Artissima 2022, and at a solo exhibition held at UGM | Maribor Art Gallery in 2022.

- 24“Mara Oláh,” Ludwig Múzeum website, https://www.ludwigmuseum.hu/en/author/olah-mara.

- 25Marina Csikós et al., “Collectively Carried Out—Tamás Péli: Birth,” in On the Same Page, ed. Rita Kálmán et al. (Budapest: OFF-Biennále Budapest, 2022), 20.

- 26Ibid.

- 27Nikolett Erőss, OFF-Biennále curator, phone conversation with author, August 2022.

- 28MoMA’s collection currently includes artworks representing the Roma—from the photographs of August Sander (1876–1964) to the paintings of Henri Rousseau (1844–1910) and Emil Nolde (1867–1956)—but it lacks works by Roma artists.