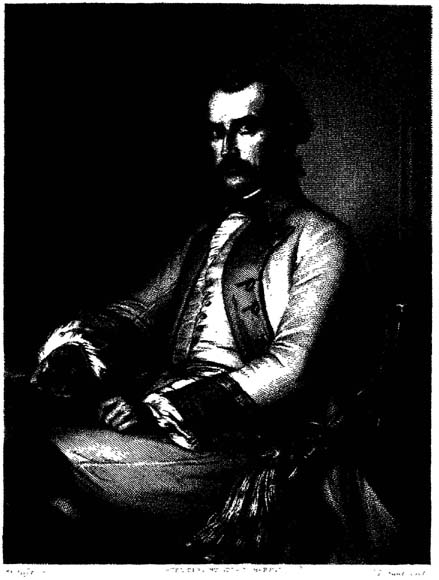

Lothario

COPYRIGHT, 1885, BY GEORGE BARRIE.

IN the shadow of a mighty rock sat Wilhelm, at a gloomy and striking spot, where the steep mountain-path turned sharply round a corner, and rapidly wound down into the chasm below. The sun was still high, and illuminated the tops of the firs in the rocky valleys at his feet. He was just entering something in his memorandum-book, when Felix, who had been clambering about, came up to him with a stone in his hand. “What do they call this stone?” said the boy.

“I do not know,” replied Wilhelm.

“Is it gold that sparkles so in it?” said the former.

“Nothing of the kind!” replied the other; “and now I remember that people call it ‘cats’-gold.’ ”*

“Cats’-gold!” said the boy, laughing; “why?”

“Probably because it is false, and because cats are thought to be false.”

“I will remember that,” said his son, and put the stone into his leathern wallet; but at the same time pulled out something else, and asked, “What is this?”

“A fruit,” replied his father; “and to judge by its scales it ought to be akin to the fir-cones.”

“It does not look like a cone; why it is round.”

“Let us ask the huntsmen: they know the whole forest and all sorts of fruits; they know how to sow, to plant, and to wait; then they let the stems grow and become as big as they can.”

“The hunters know everything; yesterday the postman showed me where a stag had crossed the road; he called me back and made me observe the track, as he called it. I had jumped across it, but now I saw plainly a pair of claws printed; it must have been a big stag.”

“I heard how you were questioning the postman.”

“He knew a great deal, and yet he is not a huntsman. But I want to be a huntsman. It is glorious to be the whole day in the forest, and to listen to the birds, to know their names and where their nests are; how to take the eggs or the young ones; how to feed them, and when to catch the old ones: all this is so splendid!”

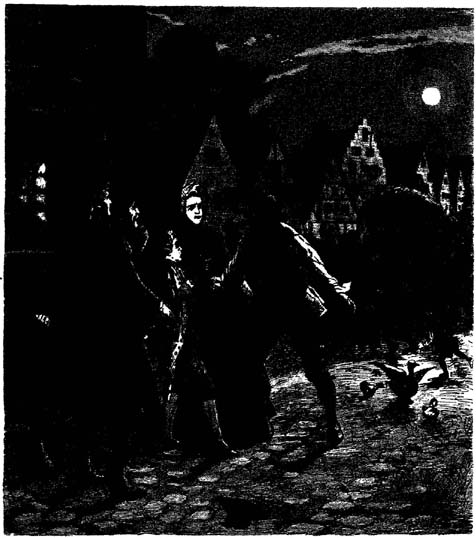

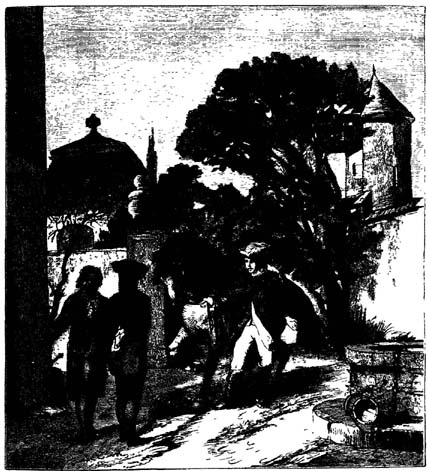

Scarcely had this been said, when there appeared coming down the rugged path an unusual phenomenon. Two boys, beautiful as the day, in colored tunics, which one might Edition: current; Page: [6] rather have taken for small shirts girt up, sprang down one after the other; and Wilhelm found an opportunity of inspecting them more closely, as they faltered before him, and for a moment stood still. Around the head of the elder one waved an abundance of fair locks, which one must needs see first on looking at him; and next his light-blue eyes attracted the glance which lost itself with pleasure in his beautiful figure. The second, who looked more like a friend than a brother, was adorned with smooth brown hair, which hung down over his shoulders, and the reflection of which seemed to mirror itself in his eyes.

Wilhelm had not time to contemplate more closely these two extraordinary, and in such a wilderness quite unexpected beings, when he heard a manly voice shouting down in a emptory yet kindly manner from behind the corner of the rock: “Why are you standing still? Do not stop the way for us!”

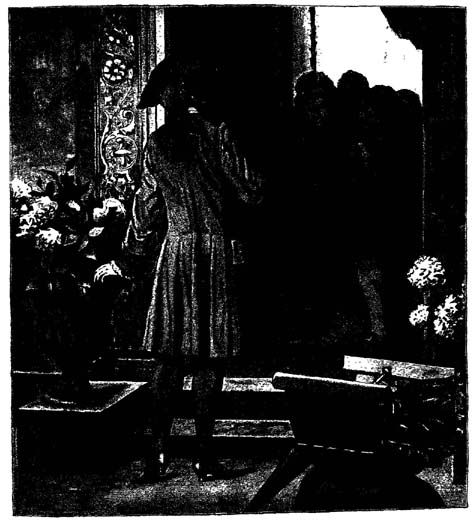

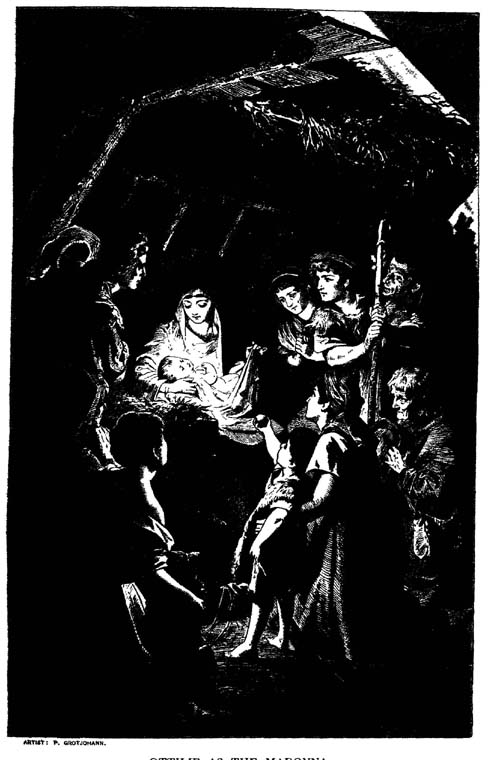

Wilhelm looked up; and if the children had caused him to wonder, what now met his eyes filled him with astonishment. A strong and vigorous, but not too tall, young man, lightly clad, with brown complexion and black hair, stepped firmly yet carefully down the rocky path, leading after him a donkey, which first displayed its own sleek and well-trimmed head, and then the beautiful burden which it carried. A gentle, lovable woman was sitting in a large finely-mounted saddle; within a blue mantle, which was wrapped round her, she held a lately-born infant, which she pressed to her bosom and regarded with indescribable love. The same thing occurred to the guide as to the children: he hesitated for a moment when he saw Wilhelm. The animal slackened its pace, but the descent was too steep—the passers-by could not stop, and Wilhelm with wonder saw them disappear behind the projecting wall of rock.

Nothing was more natural, than that this unwonted sight should snatch him from his meditations. He stood up in curiosity and looked down from his place into the depth to see whether they would not somewhere or other come into sight again. And he was just on the point of descending himself to greet these strange wanderers, when Felix came up and said:

“Father, may I not go with these children to their house? They want to take me with them. You must come too, the man said to me. Come! They are waiting down yonder.”

“I will speak to them,” answered Wilhelm.

He found them at a place where the road was less precipitous, and he devoured with his eyes the wonderful forms which had so much attracted his attention. But there were one or two other special circumstances, which before now it had not been possible for him to observe.

The young and active man had in fact an adze on his shoulder, and a long, thin, iron measuring-square.

The children carried tall bunches of bulrushes, as if they were palms; and if from this point of view they resembled angels, on the other hand they dragged along small baskets with eatables, and in this resembled the daily messengers, such as are accustomed to go to and fro across the mountain. The mother, too, when he looked at her more closely, had beneath her blue mantle a reddish delicately-tinted under-garment, so that our friend, with astonishment, was fain to find the Flight into Egypt, which he had so often seen painted, actually here before his eyes.

They greeted one another; and whilst Wilhelm, what with astonishment and absorption, could not utter a single word, the young man said:

“Our children have already made friends just now. Will you come with us, that we may see whether the grown-up people may not come to an understanding too.”

Wilhelm bethought himself a little, and then replied:

“The sight of your little family procession inspires confidence and kindliness, and—I may as well confess it at once—no less curiosity, and a lively desire to know more of you. For at the first moment one might almost ask one’s self whether you are real travellers, or only spirits who take a pleasure in animating this inhospitable mountain with pleasant visions.”

“Then come with us to our dwelling,” said the other.

“Come along!” shouted the children, already dragging Felix along with them.

“Come with us!” said the lady, turning her amiable kindly look from her babe towards the stranger.

Without hesitation, Wilhelm said:

“I am sorry that I cannot follow you immediately. This night at least I must pass at the frontier-house above. My wallet, papers and everything are still lying up there unpacked and unattended to. But, that I may Edition: current; Page: [7] show myself ready and willing to do justice to your kind invitation, I will hand you over my Felix as a pledge. To-morrow I shall be with you. How far is it from here?”

“Before sunset we shall reach our dwelling,” said the carpenter, “and from the frontier-house it will be only an hour and a half more for you. Your boy will augment our family for this night; to-morrow we shall expect you.”

The man and the beast set themselves in motion. Wilhelm with visible pleasure saw his Felix in such good company; he could compare him with the dear little angels, from whom he differed so markedly. For his years he was not tall, but robust, with a broad chest and strong shoulders. In his nature there was a peculiar mixture of authority and obedience; he had already laid hold of a palm-branch and a little basket, whereby he seemed to express both. The procession was already on the point of disappearing a second time round a rocky wall, when Wilhelm collected himself, and shouted after them:

“But how shall I inquire for you?”

“Only ask for St. Joseph’s!” rang from the depth, and the whole vision had disappeared behind the blue walls of shadow. A solemn religious hymn, sung in parts, arose and died away in the distance, and Wilhelm thought that he distinguished the voice of his Felix.

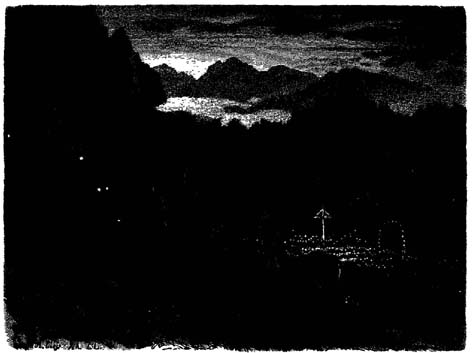

He mounted upwards, and in so doing retarded for himself the sunset. The star of heaven which he had lost more than once, shone on him again as he ascended higher, and it was still day when he arrived at his lodging. Once more he gladdened himself with the grand mountain view, and then withdrew to his chamber, where he at once seized a pen, and spent a part of the night in writing.

“Now at last is the summit reached—the heights of the mountain chain which will set a more effectual separation between us than the whole stretch of country so far. It is my feeling that one is still ever in the neighborhood of one’s beloved ones as long as the streams flow from us to them. To-day I can still fancy to myself that the twig which I cast into the forest brook might leisurely float downwards to her—might in a few days be stranded in front of her garden; and thus our spirit sends its images, our heart its feelings, more easily downwards. But over there I fear that a partition wall is placed against imagination and feeling. Yet that is perhaps only a premature anxiety; for there, too, it will very likely not be otherwise than it is here.

“What could separate me from thee—from thee, to whom I am destined for ever, although a wondrous fate keeps me from thee, and unexpectedly shuts to me the heaven to which I was standing so near! I had time to collect myself, and yet no time would have sufficed to give me this self-possession, if I had not won it from thy mouth, from thy lips, in that decisive moment. How should I have been able to tear myself away, if the indestructible thread had not been spun, which is to unite us for time and eternity.

“Still, I ought not indeed to speak of all this. I will not transgress thy tender commands. Upon this summit let it be for the last time that I utter before thee the word, separation. My life shall become a journey. I have to discharge the traveller’s special duties, and to undergo tests of a peculiar kind. How often I smile when I read through the rules which my craft has prescribed for me, and those which I myself have made! Much has been observed and much transgressed; but even at the transgression, this sheet, this witness to my last confession, my last absolution, serves me instead of an admonishing conscience, and I make a fresh start. I am on my guard, and my errors no longer rush, like mountain torrents, one upon the top of the other.

“Still, I will willingly confess to you, that I often admire those teachers and leaders of men who only impose on their disciples outward mechanical duties. They make the thing easy to themselves and to the world. For just this part of my obligations, which formerly seemed to me the most arduous and the most wonderful—this I observe most conveniently and most pleasantly.

“I must stay not more than three days under the same roof. I must leave no inn without at least removing one mile from the same. These regulations are really designed to make my years years of journeying, and to prevent the least temptation of settling down occurring to me. I have hitherto scrupulously subjected myself to this condition—nay, not once availed myself of the indulgence allowed. It is in fact here for the first time that I make a halt—that I sleep for a third night in the Edition: current; Page: [8] same bed. From here I send you many things that I have, so far, learned, observed, saved up; and then to-morrow early we descend on the other side, in the first place to a wonderful family—a holy family, I might perhaps say—about which you will find more in my diary.

“Now, farewell, and lay down this sheet with the feeling that it has only one thing to say; only one thing that it might say and repeat forever, but will not say, will not repeat, until I have the happiness to lie again at thy feet, and over thy hands to sob out all that I have had to forego.

“Morning.

“I have packed up. The postman is fastening the wallet upon his frame. The sun has not yet risen, the mists are steaming out of all the valleys, but the sky overhead is bright. We are going down into the gloomy depth, which also will soon brighten up above us. Let me send across to you my last sigh! Let my last glance towards you be still filled with an involuntary tear! I am decided and determined. You shall hear no more complaints from me; you shall only hear what happens to the wanderer. And still, whilst I wish to conclude, a thousand more thoughts, wishes, hopes, and intentions, cross one another. Fortunately they urge me away. The postman is calling, and the host is already clearing up again in my presence, as if I had gone; even as cold-hearted improvident heirs do not conceal from the departing the arrangements for putting themselves in possession.”

Already had the traveller, following on foot his porter’s steps, left steep rocks behind and above him; already were they traversing a less rugged intermediate range, ever hurrying forwards, through many a well-wooded forest, through many a pleasant meadow-ground, until at last they found themselves upon a declivity, and looked down into a carefully cultivated valley shut in all round by hills. A large monastic building, half in ruins, half in good repair, at once attracted their attention.

“This is St. Joseph’s,” said the carrier; “a great pity for the beautiful church! Only look how fresh its pillars and columns still look through the underwood and the trees, although it has been lying so many hundreds of years in ruins.”

“The convent buildings, on the other hand,” replied Wilhelm, “are still, I see, in good preservation.”

“Yes,” said the other, “a steward lives on the spot, who manages the household, and collects the rents and tithes which have to be paid here from far around.”

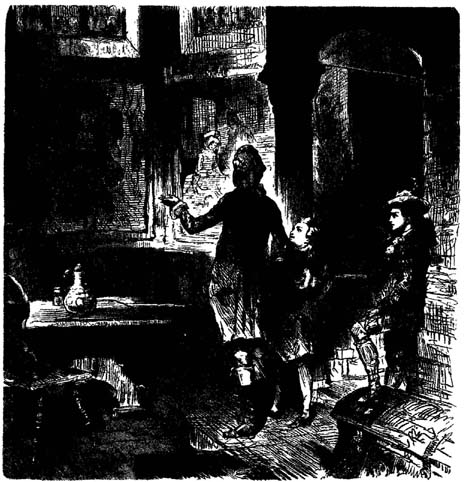

With these words they had entered, through the open gate, a spacious courtyard, which, surrounded by solemn well-preserved buildings, announced itself as the abode of a peaceful community. He at once perceived his Felix, with the angels of yesterday, busy round a big market-basket, which a strongly-built woman had placed in front of her. They were just about to buy some cherries; but in point of fact, Felix, who always carried some money about him, was beating down the price. He now played the part of host as well as guest, and was lavishing an abundance of fruit on his playmates; even to his father the refreshment was welcome amidst these barren mossy wilds, where the colored shining fruits always seemed so beautiful. “She brought them up some distance from a large garden,” the fruit-woman remarked, in order to make the price satisfactory to the buyers, to whom it had seemed somewhat too high.

“Father will soon return,” said the children; “in the meanwhile you must go into the hall and rest there.”

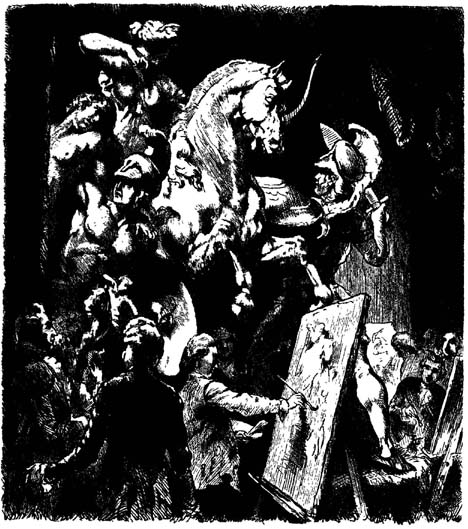

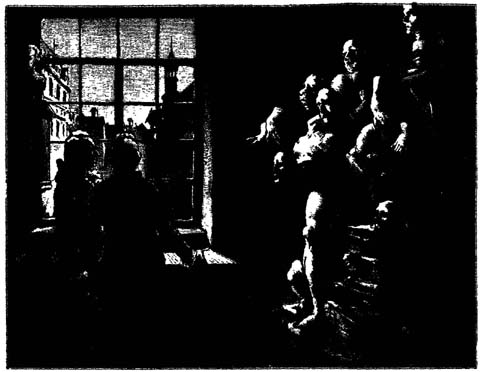

Yet how astonished was Wilhelm when the children took him to the room which they called the hall. It was entered directly from the courtyard by a large door, and our traveller found himself in a very clean well-preserved chapel, which, however, as in fact he saw, had been arranged for the domestic use of daily life. On one side stood a table, a settle, several chairs and benches; on the other side a carved dresser with various-colored pottery, jugs and glasses. There were not wanting a number of chests and boxes, and, neatly ordered as everything was, there was no want of what is attractive in domestic everyday life. The light fell through high windows at the side. But what most aroused the traveller’s attention were colored pictures painted on the wall at a moderate height below the windows, extended like tapestries round three sides of the chapel, and coming down to a panelled skirting which covered the Edition: current; Page: [9] rest of the wall to the ground. The pictures represented the history of St. Joseph. Here you saw him busy with his carpenter’s work; there he was meeting Mary, and a lily sprouted out of the ground between them, whilst several angels hovered watchfully about them. Here he is being betrothed; then follows the angelic salutation. There he is sitting despondent amidst unfinished work, letting his axe lie, and is thinking of leaving his wife. But presently there appears to him the angel in a dream, and his position is changed. With devotion he regards the new-born Child in the manger at Bethlehem, and adores it. Soon after follows a wonderfully beautiful picture. All kinds of carpentered wood are seen; it is on the point of being put together, and accidentally a couple of pieces form a cross. The Child has fallen asleep upon the cross; its mother is sitting close by regarding it with tender love, and the foster-father stops his work in order not to disturb its sleep. Immediately after follows the Flight into Egypt. It provoked a smile from the traveller as he looked at it, when he saw on the wall the repetition of the living picture of yesterday.

He had not been left long to his meditations when the host entered, whom he recognized immediately as the leader of the holy caravan. They saluted each other most cordially; a conversation on sundry matters followed; still Wilhelm’s attention remained directed towards the picture. The host saw Edition: current; Page: [10] the interest of his guest, and commenced laughingly:

“No doubt you are wondering at the harmony of this structure with its inhabitants, whom you learned to know yesterday. But it is perhaps still more strange than might be supposed; the building has, in fact, made the inhabitants. For, if the lifeless comes to life, then it may well be able also to create a living thing.”

“Oh, yes,” rejoined Wilhelm, “it would surprise me if the spirit who centuries ago worked so powerfully amid this mountain desert, and attracted towards itself such a huge mass of buildings, possessions and rights, and thereby diffused manifold culture in the neighborhood,—it would surprise me if it did not still display its vital energy even out of these ruins upon a living human being. Still, let us not abide by the general; make me acquainted with your history, in order that I may learn how it was possible that, without trifling or pretension, the past is again represented in you, and that which is past and gone comes a second time upon the scene.”

Just as Wilhelm was expecting an instructive answer from the lips of his host, a friendly voice in the courtyard shouted the name of Joseph. The host heard it, and went to the door.

So he is called Joseph, too! said Wilhelm to himself. That is wonderful enough, and yet not quite so wonderful as that he represents his patron saint in the life. At the same time he glanced towards the door, and saw the Madonna of yesterday speaking with her husband. At last they separated; the woman went to the opposite dwelling.

“Mary!” he shouted after her, “just a word more.”

So she is called Mary, too! But a little more, and I shall feel myself transported backwards eighteen hundred years. He mused on the solemn pent-up valley in which he found himself, on the ruins and the stillness, and a strange olden-time sort of mood fell upon him. It was time that the host and children came in. The latter begged Wilhelm to come for a walk, whilst the host still discharged a few duties. They went now through the ruins of the church, with its wealth of columns: the lofty roof and walls seemed to strengthen themselves in wind and storm; whilst strong trees had, ages ago, struck root in the broad tops of the walls, and in company with a good deal of grass, flowers, and moss, represented gardens hanging boldly in the air. Grassy meadow-paths led to a rapid brook, and the traveller could now, from a certain height, look over the building and its situation with an interest which grew greater as its inhabitants became more and more remarkable to him, and, through their harmony with their surroundings, aroused his liveliest curiosity.

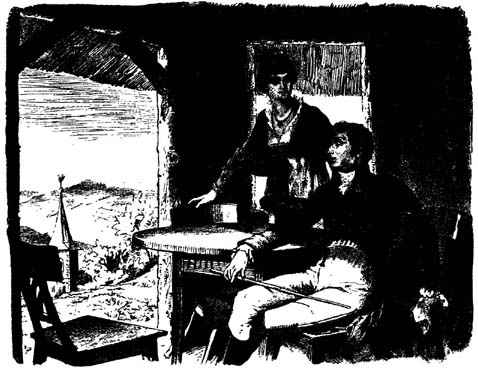

They returned, and found a table laid in the consecrated hall. At the upper end there stood an arm-chair, in which the housewife sat down. She had standing by her side a high basket, in which the little child was lying; next, the father on her left hand, and Wilhelm on her right. The three children occupied the lower part of the table. An old female servant brought in a well-prepared repast. The eating and drinking-vessels likewise indicated a bygone time. The children gave occasion for amusement, whilst Wilhelm could not look enough at the figure and bearing of his holy hostess.

After dinner the company separated; the host took his guest to a shady spot in the ruins, where from an elevated position one had in full view the pleasant prospect down the valley, and saw the hills of the lower land, with their fertile declivities and woody summits ranged one behind the other.

“It is fair,” said the host, “that I should satisfy your curiosity, and the rather as I feel, in your case, that you are capable of taking the marvellous seriously, if it rests upon a serious foundation. This religious institution, of which you still see the remains, was dedicated to the holy family, and in olden times, on account of many miracles, was renowned as a place of pilgrimage. The church was dedicated to the mother and the son. It was destroyed several centuries ago. The chapel, dedicated to the holy foster-father, has been preserved, as also the habitable part of the convent. The income for a great many years back has belonged to a secular prince, who keeps an agent up here, and that am I, the son of the former agent, who likewise succeeded his father in this office.

“St. Joseph, although all ecclesiastical honors had long ago ceased up here, had been so beneficent towards our family, that it is not to be wondered at, if they felt particularly well disposed towards him; and thence it came to pass, that at baptism I was called Joseph, whereby to a certain extent my manner of life was determined. I grew up, and if I became Edition: current; Page: [11] an associate of my father whilst he looked after the rents, still I clung quite as much, nay, even more affectionately, to my mother, who according to her means was fond of distributing relief, and through her kindly disposition and her good deeds was known and beloved on the whole mountain-side. She would send me, now here, and now there; at one time to fetch, at another to order, at another to look after; and I felt quite at home in this kind of charitable business.

“In general a mountain life has something more humanizing than life on the lowlands; inhabitants are closer together, or further apart, if you wish it; wants are smaller, but more pressing. Man is more thrown upon his own resources,—must learn to rely on his hands, on his feet. The laborer, postman, carrier, are all united in one and the same person; everybody also stands nearer to his neighbor, meets him oftener, and lives with him in a common sphere of activity.

“When I was still young, and my shoulders unable to carry much, it occurred to me to furnish a small donkey with baskets, and drive it before me up and down the steep footpaths. In the mountains, the ass is no such contemptible animal as in the lowlands, where the laborer who ploughs with horses thinks himself better than another who tears up the sod with oxen. And I trudged along behind my beast with all the less misgiving, that I had before noticed, in the chapel, that it had attained to the honor of carrying God and his mother. Still, this chapel was not then in the condition in which it is now. It was treated like an outbuilding, almost like a stable. Firewood, hurdles, tools, tubs and ladders, and all sorts of things, were heaped pell-mell together. It was fortunate that the paintings were situated so high, and that wainscot lasts a little while. But as a child I was especially fond of clambering here and there all about the wood, and looking at the pictures, which nobody could properly explain to me. Enough, I knew that the saint whose life was painted above was my namesake, and I congratulated myself on him, as much as if he had been my uncle. I grew up, and as it was a special condition that he who would lay claim to the profitable office of steward must exercise a trade, therefore, in accordance with the wish of my parents, who were anxious that I should one day inherit this excellent post, I was to learn a trade—and, moreover, such a one as would prove useful to the household up here.

“My father was a cooper by trade, and made everything of this sort of work that was necessary himself, whence accrued great advantage to himself and the whole family. But I could not make up my mind to follow him in this line. My inclination drew me irresistibly towards the carpenter’s trade, the implements of which I had from my youth seen so circumstantially and correctly painted by the side of my saint. I declared my wish; they did not oppose it, and the less so as the carpenter was often required by us for so many different constructions, and even because, if he has some ability and love for his work, the cabinet-maker’s and wood-carver’s arts, especially in forest districts, are closely allied to it. And what still more strengthened me in my higher designs was that picture, which, alas! now is almost entirely obliterated. As soon as you know what it is meant to represent, you will be able to make it out, when I take you to it presently. St. Joseph had been entrusted with nothing less than the making of a throne for King Herod. The gorgeous seat was to be placed between two specified pillars. Joseph carefully takes the measure of the breadth and height, and constructs a costly royal throne. But how astonished is he, how distracted, when he brings the chair of state: it is found to be too high and not wide enough. Now, as is well known, King Herod was not to be trifled with: the pious master-joiner is in the greatest embarrassment. The Christ-child, accustomed to accompany him everywhere, to carry his tools in childishly humble sport, sees his distress, and is immediately ready with advice and help. The wondrous Child desires his foster-father to take hold of the throne by one side. He seizes the other side of the carved work, and both begin to pull. With the greatest ease and as conveniently as if it had been of leather, the throne expands in breadth, loses proportionately in height, and fits most excellently to the place and position, to the greatest consolation of the reassured carpenter and to the perfect satisfaction of the king.*

“In my youth that throne was still quite easy to see, and from the remains of one side you will be able to observe that there was no Edition: current; Page: [12] lack of carved work, which indeed must have proved easier to the painter than it would have been to the carpenter, if it had been demanded of him.

“However, I had no misgivings in consequence, but looked upon the craft to which I had devoted myself in such a favorable light, that I could scarcely wait until they had put me into apprenticeship; which was all the more easy to effect, inasmuch as there lived in the neighborhood a master-carpenter who worked for the whole district, and who could employ several assistants and apprentices. Thus I remained near my parents, and continued to a certain extent my former life, whilst employing hours of leisure and holy-days for the charitable commissions with which my mother continued to charge me.

“In this way a few years passed,” continued the narrator. “I very soon understood the advantages of the craft; and my body, developed through work, was capable of undertaking anything required for the purpose. In addition, I discharged the former duties which I rendered to my good mother, or rather to the sick and needy. I went with my beast through the mountain, distributed the load punctually, and from grocers and merchants I took back with me what we lacked up here. My master was satisfied with me, and so were my parents. Already I had on my wanderings the pleasure of seeing many a house which I had helped to erect, which I had decorated. For it was especially this last—the notching of the beams, the carving of certain simple forms, the branding of ornamental figures, the red-coloring of certain cavities, by which a wooden mountain-house offers such a cheerful aspect,—all such performances were entrusted to me especially, because I showed myself best in the matter, always bearing in mind as I did the throne of Herod and its adornments.

“Among the help-worthy persons of whom my mother took particular care, the first place was especially awarded to young wives in expectation of childbed, as I by degrees could well observe, although in such cases it was usual to keep the messages a secret so far as I was concerned. In such cases I never had any direct commission, but everything went through the medium of a good woman who lived at no great distance down the valley, and who was called Frau Elizabeth. My mother, herself experienced in the art which rescues for life so many at the very entrance into life, was on unalterably good terms with Frau Elizabeth, and I often had to hear on all sides that many of our robust mountaineers had to thank both these women for their existence. The mystery with which Elizabeth every time received me, her reserved answers to my puzzling questions, which I myself did not understand, awoke in me a particular reverence for her and her house, which was in the highest degree clean, and seemed to me to represent a kind of little sanctuary.

“In the meanwhile, in consequence of my knowledge and skill in my trade, I had acquired a certain amount of influence in the family. As my father, in his quality of cooper, had provided for the cellar, so did I now care for house and home, and mended many injured portions of the ancient building. I particularly succeeded in restoring to domestic use certain dilapidated out-houses and coach-houses; and scarcely was this done, than I set about clearing and cleansing my beloved chapel. In a few days it had been put in order, almost as you see it; whereupon I set about restoring, in uniformity with the whole, the missing or injured parts of the panel-work. And you might perhaps take these folding-doors of the entrance to be rather old, but they are my own work. I have spent several years in carving them in hours of leisure, after I had in the first place neatly joined them into a whole by the aid of strong planks of oak. Whatever of the pictures had not up to that time been injured or obliterated, has also been preserved up to now; and I assisted the glazier at a new building on the condition that he restored the colored windows.

“If those pictures and thoughts on the life of the saint had occupied my imagination, so it all became only more deeply impressed upon me when I was able to consider the spot as once more a sanctuary, and while away the time in it, particularly in the summer, and meditate at leisure upon whatever I saw or imagined. I felt within me an irresistible inclination to imitate the saint; and, as similar circumstances cannot easily be called forth, I determined at least to begin to resemble him from below, as in fact I had already begun to do long ago by the use of the beast of burden. The little creature of which I had availed myself hitherto would Edition: current; Page: [a] Edition: current; Page: [b] Edition: current; Page: [13] not suffice me any longer. I found for myself a much finer animal, and was careful to get a well-constructed saddle, which was equally convenient for riding or for carrying goods. A pair of new baskets were procured, and a net with colored ribbons, tassels, and knots, mingled with chinking metal tags, adorned the neck of the long-eared creature, which was now soon able to vie with its prototype on the wall. It occurred to no one to mock me, when in this array I passed along the mountain; for people willingly allow benevolence a marvellous outward aspect.

JOSEPH AND MARY.

“In the meantime the war, or rather its consequences, had approached our district, whilst on several occasions dangerous bands of runaway rascals collected together, and here and there perpetrated many a violent deed and much mischief. By a good system of country militia, patrols, and continuous vigilance, the evil was certainly very soon quelled; yet people too soon fell into carelessness again, and, before they had become aware of it, fresh mischiefs broke out.

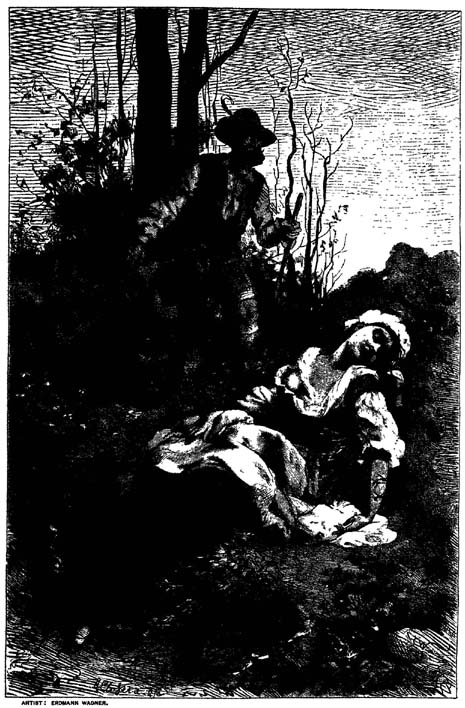

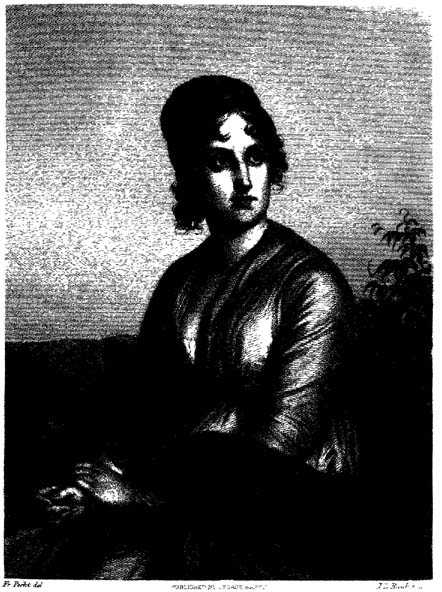

“There had long been quiet in our district, and I with my sumpter beast went peacefully trudging along the accustomed paths, until, on a certain day, I came across the newly-sown clearing in the wood, and on the edge of the sunk fence I found sitting, or rather lying, a female figure. She seemed to be asleep or in a swoon. I attended to her, and when she opened her beautiful eyes, and sat up, she exclaimed passionately, ‘Where is he? Have you seen him?’

“ ‘Whom?’ I asked.

“She answered, ‘My husband!’

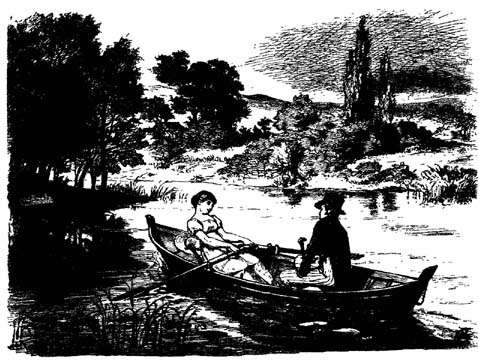

“Seeing how very youthful her aspect was, this answer was not expected by me; still, I continued to assist her only the more readily, and to assure her of my sympathy. I gathered that the two travellers had left their carriage at some distance, on account of the difficult carriage-road, in order to turn into a shorter foot-path. Close by the spot they had been assailed by armed men: her husband, whilst fighting, had got to some distance off. She had not been able to follow him far, and had been lying on this spot she did not know how long. She begged me imploringly to leave her and to hurry in search of her husband. She got upon her feet, and the most beautiful, the loveliest form stood before me; yet I could easily see that she was in a condition in which she might very soon need the assistance of my mother and Frau Elizabeth. We disputed for a while, for I wished first to take her to a place of safety; she wished first of all for news of her husband. She would not go far herself from the path he had taken, and all my representations would perhaps have proved fruitless, if a troop of our militia, which had turned out upon the news of fresh outrages, had not just then arrived through the forest. They were informed of what had happened; the necessary course was agreed upon, the place of meeting Edition: current; Page: [14] fixed, and thus the matter was so far set straight. I quickly hid my basket in a neighboring cave, which had already often served me as a storehouse, arranged my saddle into a comfortable seat, and lifted, not without a peculiar emotion, the lovely burden upon my willing beast, which was able by itself to find the familiar paths at once, and gave me an opportunity of walking along by her side.

“You may imagine, without my describing at length, in what a strange state of mind I was. What I so long had sought for I had really found. I felt as if I were dreaming, and then again, suddenly, as if I had awoke from a dream. This heavenly form, as I saw it hovering as it were in the air, and moving in front of the green trees, came before me now like some dream, which was called forth in my soul through those pictures in the chapel. Then, again, those pictures seemed to me to have been only dreams, which now resolved themselves into a beautiful reality. I questioned her on many things; she answered me gently and politely, as beseems a person of good standing, in trouble. She often begged me, when we reached some open height, to stand still, look round, and listen. She begged me with such grace, with such a deeply-imploring glance from beneath her long black eyelashes, that I had to do whatever was but possible: I actually climbed an isolated, tall, and branchless fir-tree. Never had this evidence of my dexterity been more welcome to me; never had I on holidays and at fair-times with greater satisfaction fetched down ribbons and silk handkerchiefs from similar altitudes. Yet this time I went, alas! without any prize; neither did I see or hear anything from above. At last she herself called to me to come down, and beckoned to me quite urgently with her hand; nay, when at length in sliding down I let go my hold at a considerable height and jumped down, she gave a cry, and a sweet friendliness overspread her face, when she saw me uninjured before her.

“Why should I detain you long with the hundred attentions with which I tried to make the whole way pleasant to her, in order to distract her thoughts. And how too could I?—for this is just the peculiar quality of true attentiveness, that for the moment it makes everything of nothing. To my own feeling, the flowers which I plucked for her, the distant landscapes which I showed her, the mountains, forests, which I named to her, were so many precious treasures, which I seemed to present to her in order to bring myself into relation with her, as one will try to do by the aid of gifts.

“She had already gained me for my whole life, when we arrived at our destination in front of that good woman’s door, and I at once saw a painful separation before me. Once more I cast a glance over her whole form, and when my eyes had reached her feet, I stooped down, as if I had to do something to the saddlegirth, and I kissed the prettiest shoe that I had ever seen in my life, but without her perceiving it. I helped her down, sprang up the steps and shouted into the house-door: ‘Frau Elizabeth, here is a visitor for you!’ The good woman came out, and I looked over her shoulders towards the house, when the lovely being, with charming sorrow and inward consciousness of pain, mounted the steps and then affectionately embraced my worthy old woman, and let her conduct her into the better room. They shut themselves within it, and I remained standing by my ass before the door, like one who has unladen costly goods, and has again become but a poor driver as before.

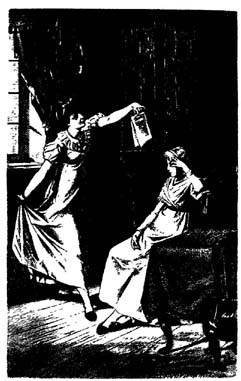

“I was still hesitating to leave the spot, for I was irresolute as to what I should do, when Frau Elizabeth came to the door and asked me to summon my mother to her, and then to go about the neighborhood and obtain if possible some news of the husband. ‘Mary begs you particularly to do this,’ said she.

“ ‘Can I not speak to her once more?’ answered I.

“ ‘That will not do,’ said Frau Elizabeth, and we parted.

“In a short time I reached our dwelling; my mother was ready to go down the very same evening and assist the young stranger. I hurried down to the lower district and hoped to obtain the most trustworthy news at the bailiff’s. But he was himself still in uncertainty, and as he knew me he invited me to spend the night with him. It seemed to me interminably long, and I constantly had the beautiful form before my eyes, as she sat rocking to and fro on the animal, and looked down at me with such a look of sorrowful friendliness. Every moment I hoped for news. I did not grudge, but wished for the preservation of the good husband, and yet Edition: current; Page: [15] could so gladly think of her as a widow. The flying detachment by degrees came together again, and after a number of varying reports the truth at last was made clear, that the carriage had been saved, but that the unfortunate husband had died of his wounds in the neighboring village. I also heard, that according to the previous arrangement some had gone to announce the sorrowful news to Frau Elizabeth. I had accordingly nothing more to do, or aid in, there, and yet a ceaseless impatience, a boundless longing, drove me back through mountain and forest to her door. It was night; the house was shut up. I saw light in the rooms, I saw shadows moving on the curtains, and so I sat down upon a bench opposite, continually on the point of knocking, and continually held back by various considerations.

“Yet why do I go on relating circumstantially what in point of fact has no interest. Enough! Even the next morning they did not let me into the house. They knew the sad occurrence, they did not want me any more; they sent me to my father, to my work; they did not answer my questions; they wanted to get rid of me.

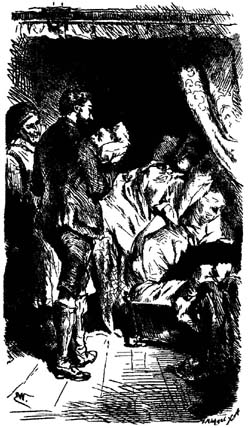

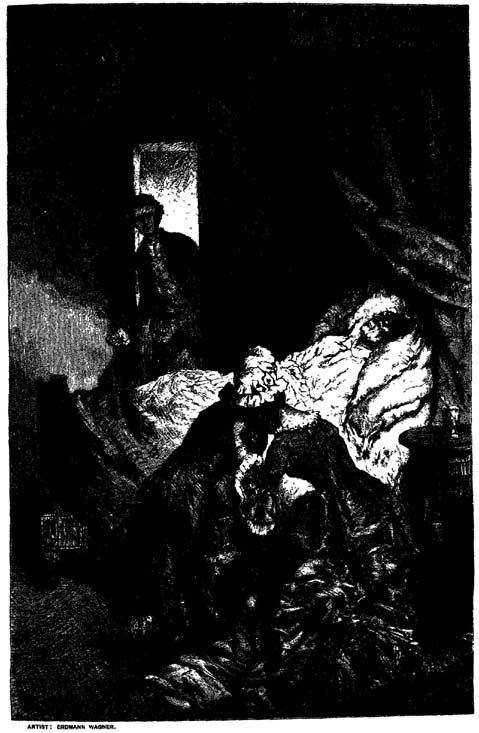

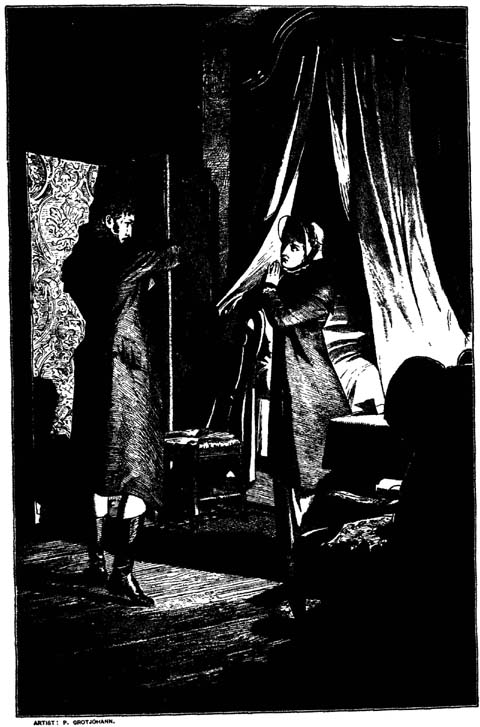

“They had been treating me this way for a week, when at last Frau Elizabeth called me in. ‘Tread gently, my friend,’ she said; ‘but come in with good comfort!’ She led me into a cleanly apartment, where, in the corner, through the half-opened bed-curtains, I saw my fair one sitting. Frau Elizabeth went to her as if to announce me, lifted something from the bed and brought it towards me: a most beautiful boy wrapped in the whitest of linen. Frau Elizabeth held him just between me and his mother, and upon the spot there occurred to me the lily-stalk in the picture, growing out of the earth between Mary and Joseph,* in witness of a pure relationship. From that instant my heart was relieved of all oppression; I was sure of my aim and of my happiness. I could freely walk towards her, speak to her; I could bear her heavenly look, take the boy in my arms, and press a hearty kiss upon his brow.

“ ‘How I thank you for your affection for this orphan child!’ said the mother.

“I exclaimed, thoughtlessly, and passionately: ‘It is an orphan no longer, if you are willing!’

“Frau Elizabeth, wiser than I, took the infant from me, and managed to send me away.

“The recollection of that time still serves me constantly for my happiest diversion when I am obliged to roam through our mountains and valleys. I am still able to call to mind the smallest circumstance—which, however, it is but fair that I should spare you.

“Weeks passed by: Mary had recovered and I could see her more frequently. My intercourse with her was a series of services and attentions. Her family circumstances allowed her to live where she liked. At first she stayed with Frau Elizabeth; then she visited us, to thank my mother and me for so much friendly help. She was happy with us, and I flattered myself that this came to pass partly on my account. Yet, what I should have liked so much to say, and dared not say, was finally mooted in a strange and charming fashion when I took her into the chapel, which I had already transformed into a habitable hall. I showed and explained to her the pictures one after the other, and in so doing I expatiated in such a vivid heartfelt manner upon the duties of a foster-father, that tears came into her eyes, and I could not get to the end of my description of the pictures. I thought myself sure of her affection, although I was not presumptuous enough to wish to blot out so soon the memory of her husband. The law compels widows to one year of mourning; and certainly such a period, which comprehends within it the change of all earthly things, is necessary to a sensitive heart, in order to soothe the painful impressions of a great loss. One sees the flowers fade and the leaves fall, but one also sees fruits ripen and fresh buds germinate. Life belongs to the living, and he who lives must be prepared for a change.

“I now spoke to my mother about the matter which I had most at heart. She thereupon revealed to me how painful the death of her husband had been to Mary, and how she had recovered again only at the thought that she must live for the sake of the child. My attachment had not remained unknown to the women, and Mary had already familiarized herself with the notion of living with us. She stayed some time longer in the neighborhood, then she came up here to us, and we lived for a while longer in the godliest and happiest state of betrothal. At last we were united. Edition: current; Page: [16] That first feeling which had brought us together did not disappear. The duties and joys of foster-father and father were combined; and thus our little family, as it increased, surpassed indeed its pattern in the number of its individuals, but the virtues of that example, in truth and purity of mind, were kept holy and practised by us. And hence also we maintain with kindly habitude the outward appearance which we have accidentally acquired, and which suits so well our inward disposition; for although we are all good walkers and sturdy carriers, yet the beast of burden remains constantly in our company, in order to carry one thing or another, when business or a visit obliges us to go through these mountains and valleys. As you met us yesterday, so the whole neighborhood knows us; and we are proud of the fact that our conduct is of a kind not to shame those holy names and persons whom we profess to follow.”

“I have just ended a pleasant half wondrous story, which I have written down for thee from the lips of an excellent man. If it is not entirely in his own words—if here and there I have expressed my own feelings in the place of his, this is quite natural, in view of the relationship I have here felt with him. Is not that veneration for his wife like that which I feel for you? And has not even the meeting of these two lovers some likeness to our own? But, that he is happy enough in walking along by the side of the beast that carries its double burden of beauty; that in the evening he can, with his family following, enter through the old convent gates, and that he is inseparable from his beloved and from his children;—all this I may be allowed to envy him in secret. On the other hand, I must not complain of my own fate, since I have promised you to be silent and to suffer, as you also have undertaken to do.

“I have to pass over many beautiful features of the common life of these virtuous and happy people; for how could everything be written? A few days I have spent pleasantly, but the third already warns me to bethink me of my further travels.

“To-day I had a little dispute with Felix, for he wanted almost to compel me to transgress one of the good intentions which I have promised you to keep. Now it is just a defect, a misfortune, a fatality with me, that, before I am aware of it, the company increases around me, and I charge myself with a fresh burden, under which I afterwards have to toil and to drag myself along. Now, during my travels, we must have no third person as a constant companion. We wish and intend to be and to remain two only, and it has but just now seemed as if a new, and not exactly pleasing connection was likely to be formed.

“A poor, merry little youngster had joined the children of the house, with whom Felix had been enjoying these days in play, who allowed himself to be used or abused just as the game required, and who very soon won the favor of Felix. From various expressions I noticed already that the latter had chosen a playmate for the next journey. The boy is known here in the neighborhood; he is tolerated everywhere on account of his merriness, and occasionally receives gratuities. But he did not please me, and I begged the master of the house to send him away. This was accordingly done, but Felix was vexed about it, and there was a little scene.

“On this occasion I made a discovery which pleased me. In a corner of the chapel, or ball, there stood a box of stones, which Felix—who since our wandering through the mountain had become exceedingly fond of stones—eagerly pulled out and examined. Among them were some fine, striking specimens. Our host said that the child might pick out for himself any he liked: that these stones were what remained over from a large quantity which a stranger had sent from here a short time before. He called him Montan,* and you can fancy how glad I was to hear this name, under which one of our best friends, to whom we owe so much, is travelling. As I inquired as to time and circumstances, I may hope soon to meet with him in my travels.”

The news that Montan was in the neighborhood had made Wilhelm thoughtful. He considered that it ought not to be left merely to chance whether he should see such a worthy friend again, and therefore he inquired of his host whether it was not known in what direction this traveller had bent his way. No one had any more exact knowledge of this, and Edition: current; Page: [17] Wilhelm had already determined to pursue his route according to the first plan, when Felix exclaimed, “If father were not so obstinate, we should soon find Montan.”

“In what manner?” asked Wilhelm.

Felix answered: “Little Fitz said yesterday that he would most likely follow up the gentleman who had the pretty stones with him, and knew so much about them too.”

After some discussion Wilhelm at last resolved to make the attempt, and in so doing to give all the more attention to the suspicious boy. He was soon found, and when he understood what was intended, he brought a mallet and iron, and a very powerful hammer, together with a bag, and, in this miner-like equipment, ran merrily in front.

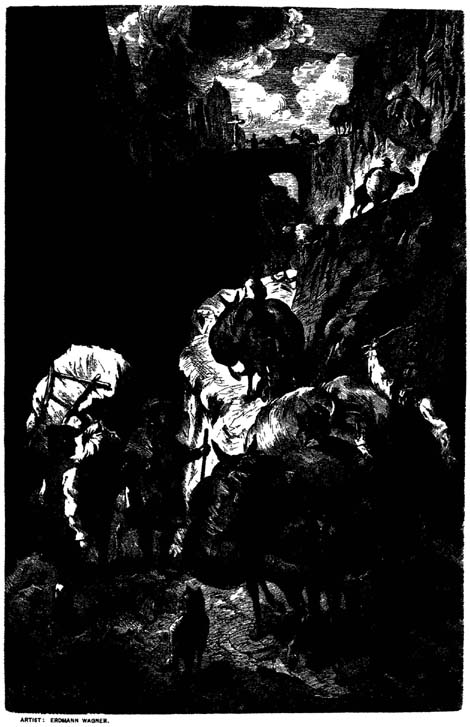

The road led sideways up the mountain again. The children ran leaping together from rock to rock, over stock and stone, and brook and stream, without following any direct path. Fitz, glancing now to his right and now to his left, pushed quickly upwards. As Wilhelm, and particularly the loaded carrier, could not follow so quickly, the boys retraced the road several times forwards and backwards, singing and whistling. The forms of certain strange trees aroused the attention of Felix, who, moreover, now made for the first time the acquaintance of the larches and stone-pines, and was attracted by the wonderful gentians. And thus the difficult travelling from place to place did not lack entertainment.

Edition: current; Page: [18]Little Fitz suddenly stood still and listened. He beckoned to the others to come.

“Do you hear the knocking?” said he. “It is the sound of a hammer striking the rock.”

“We hear it,” said the others.

“It is Montan,” said he, “or someone who can give us news of him.”

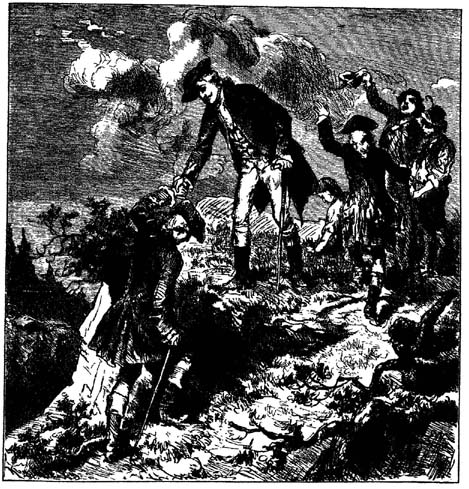

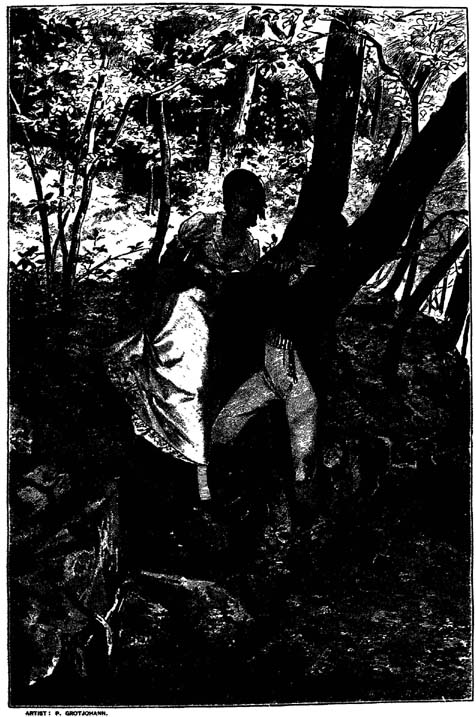

As they followed the sound, which was repeated at intervals, they struck a clearing in the forest, and beheld a steep, lofty, naked rock, towering above everything, leaving even the tall forests under it. On the summit they descried a person. He stood at too great a distance to be recognized. The children at once commenced to clamber up the rugged paths. Wilhelm followed with some difficulty, nay, danger: for in ascending a rock, the first one goes more safely, because he feels his way for himself; the one that follows only sees where the former has got to, but not how. The boys soon reached the top, and Wilhelm heard a loud shout of joy.

“It is Jarno!” Felix called out to his father, and Jarno at once stepped forward to a steep place, reached his hand to his friend, and pulled him up to the top. They embraced and welcomed each other with rapture under the open canopy of heaven.

But they had scarcely let each other go when Wilhelm was seized with giddiness, not so much on his own behalf, as because he saw the children hanging over the fearful precipice. Jarno noticed it, and told them all to sit down at once.

“Nothing is more natural,” said he, “than to feel giddy before any great sight, upon which we come unexpectedly, and so feel at the same time our littleness and our greatness. But then, generally speaking, there is no true enjoyment except where one must at first feel giddy.”

“Are those below these the big mountains which we have crossed?” asked Felix. “How little they look! And here,” he continued, loosening a little piece of stone from the top, “here is the cats’-gold again; it seems to be everywhere!”

“It is found far and wide,” replied Jarno; “and since you are curious about such things, take notice that at present you are sitting upon the oldest mountain range, on the earliest form of stone, in the world.”

“Was not the world made all at once, then?” asked Felix.

“Scarcely,” replied Montan; “good things require time.”

“Then down there there is another sort of stone,” said Felix, “and then again another, and others again, forever,” pointing from the nearest mountains towards the more distant ones, and so to the plains below.

It was a very fine day, and Jarno pointed out in detail the splendid view. Here and there stood several other summits like that upon which they were. A mountain in the middle distance seemed to vie with it, but still was far from reaching the same height. Farther off it was less and less mountainous; yet strangely prominent forms still showed themselves. Lastly, in the distance even the lakes and rivers became discernible, and a fertile region seemed to spread itself out like a sea. If the eye was brought back again it penetrated into fearful depths, traversed by roaring cataracts, depending one upon the other in labyrinthine confusion.

Felix was never weary of asking questions, and Jarno was accommodating enough in answering every question for him: in which, however, Wilhelm thought that he noticed that the teacher was not altogether truthful and sincere. Therefore, when the restless boys had clambered farther away, he said to his friend:

“You have not spoken to the child about these things as you speak with yourself about them.”

“That is rather a burdensome demand,” answered Jarno; “one does not always speak even to one’s self as one thinks, and it is our duty to tell others only what they can comprehend. Man understands nothing but what is proportionate to him. The best thing one can do, is to keep children in the present—to give them a name or a description. In any case they ask soon enough for the reasons.”

“They are not to be blamed for that,” answered Wilhelm. “The complicated nature of objects confuses everybody, and instead of dissecting them it is more convenient to ask quickly, Whence? and whither?”

“And yet,” continued Jarno, “as children only see objects superficially, one can only speak to them superficially about their origin and purpose.”

“Most people,” answered Wilhelm, “remain for their whole life in this condition, and do not reach that glorious epoch, in which the intelligible becomes commonplace and foolish to us.”

“One may indeed call it glorious,” replied Jarno; “for it is a middle state between desperation and deification.”

Edition: current; Page: [19]“Let us keep to the boy, who is now my chief anxiety,” said Wilhelm. “Now he has acquired an interest in minerals since we have been travelling. Can you not impart to me just enough to satisfy him at least for a time?”

“That will not do,” said Jarno; “in every new intellectual sphere one has first to commence like a child again, throw a passionate interest into the matter, and rejoice first in the outward husk before one has the happiness of reaching the kernel.”

“Then tell me,” answered Wilhelm, “how have you arrived at this knowledge and insight?—for it is still not so long since we parted from one another!”

“My friend,” replied Jarno, “we had to resign ourselves, if not for always, at least for a long time. The first thing that under such circumstances occurs to a brave man, is to commence a new life. New objects are not enough for him; these are only good as a distraction; he demands a new whole, and at once places himself in the centre of it.”

“But why,” interrupted Wilheim, “just this passing strange, this most solitary of all prepossessions?”

“Just for this reason,” exclaimed Jarno: “because it is hermit-like! I would avoid men. We cannot help them, and they hinder us from helping ourselves. If they are happy one must leave them alone in their vanity; if they are unhappy one must save them without injuring this vanity; and no one ever asks whether you are happy or unhappy.”

“But things are not yet quite so bad with them,” replied Wilhelm, laughing.

“I will not rob you of your happiness,” said Jarno. “Only journey onward, thou second Diogenes! Let not your little lamp be extinguished in broad daylight! Yonder, below, there lies a new world before you; but I will wager it goes on just like the old one behind us. If you cannot mate yourself and pay debts, you are of no use among them.”

“However,” replied Wilhelm, “they seem to me more amusing than those stubborn rocks of yours.”

“Not at all,” replied Jarno, “for the latter are at least incomprehensible.”

“You are trying to evade,” said Wilhelm, “for it is not in your way to deal with things which leave no hope of being comprehended. Be sincere, and tell me what you have found in this cold, stern hobby of yours?”

“That is difficult to tell of any hobby, particularly of this one.”

Then he reflected for a moment, and said:

“Letters may be fine things, and yet they are insufficient to express sounds: we cannot dispense with sounds, and yet they are a long way from sufficient to enable mind, properly so called, to be expressed aloud. In the end, we cleave to letters and to sound, and are no better off than if we had renounced them altogether: what we communicate, and what is imparted to us, is always only of the most commonplace, by no means worth the trouble.”

“You want to evade me,” said his friend; “for what has that to do with these rocks and pinnacles?”

“But suppose,” replied the other, “that I treated these very rents and fissures as if they were letters: sought to decipher them, fashion them into words, and learned to read them off-hand: would you have anything against that?”

“No, but it seems to me an extensive alphabet.”

“More limited than you think: one has only to learn it like any other one. Nature possesses only one writing, and I have no need to drag along with a number of scrawls. Here I have no occasion to fear—as may happen after I have been long and lovingly poring over a parchment—that an acute critic will come and assure me that everything is only interpolated.”

“And yet even here,” replied his friend, laughing, “your methods of reading are contested.”

“Even for that very reason,” said the other, “I do not talk with anybody about it; and with you too, just because I love you, I will no longer exchange and barter the wretched trash of empty words.”

The two friends, not without care and difficulty, had descended to join the children, who had settled themselves in a shady spot below. The mineral specimens collected by Montan and Felix were unpacked almost more eagerly than the provisions. The latter had many questions to ask, and the former many names to pronounce. Felix was delighted that he could tell him the names of them all, Edition: current; Page: [20] and committed them quickly to memory. At last he produced one more stone, and said, “What is this one called?”

Montan examined it with astonishment, and said, “Where did you get it?”

Fitz answered quickly, “I found it; it comes from this country.”

“It is not from this district,” replied Montan.

Felix enjoyed seeing the great man somewhat preplexed.

“You shall have a ducat,” said Montan, “if you take me to the place where it is found.”

“It will be easy to earn,” replied Fitz, “but not at once.”

“Then describe to me the place exactly, so that I shall be able to find it without fail. But that is impossible, for it is a cross-stone, which comes from St. James of Compostella, and which some foreigner has lost, if indeed you have not stolen it from him, because it looks so wonderful.”

“Give your ducat to your friend to take care of,” said Fitz, “and I will honestly confess where I got the stone. In the ruined church at St. Joseph’s there is a ruined altar as well. Among the scattered and broken stones at the top I discovered a layer of this stone, which served as a bed for the others, and I knocked down as much of it as I could get hold of. If you only lifted away upper stones, no doubt you would find a good deal more of it.”

“Take your gold-piece,” replied Montan; “you deserve it for this discovery. It is a pretty one. One justly rejoices when inanimate nature brings to light a semblance of what we love and venerate. She appears to us in the form of a sibyl, who sets down beforehand evidence of what has been predestined from eternity, but can only in the course of time become a reality. Upon this, as upon a miraculous, holy foundation, the priests had set their altar.”

Wilhelm, who had been listening for a time, and who had noticed that many names and many descriptions came over and over again, repeated his already expressed wish that Montan would tell him so much as he had need of for the elementary instruction of the boy.

“Give that up,” replied Montan. “There is nothing more terrible than a teacher who does not know more than the scholars, at all events, ought to know. He who wants to teach others may often indeed be silent about the best that he knows, but he must not be half-instructed himself.”

“But where, then, are such perfect teachers to be found?”

“You can find them very easily,” replied Montan.

“Where, then?” said Wilhelm, with some incredulity.

“Wherever the matter which you want to master is at home,” replied Montan. “The best instruction is derived from the most complete environment. Do you not learn foreign languages best in the countries where they are at home—where only those given ones and no other strike your ear?”

“And have you then,” asked Wilhelm, “attained the knowledge of mountains in the midst of mountains?”

“Of course.”

“Without conversing with people?” asked Wilhelm.

“At least only with people,” replied the other, “who were familiar with mountains. Wheresoever the Pygmies, attracted by the metalliferous veins, bore their way through the rock to make the interior of the earth accessible, and by every means try to solve problems of the greatest difficulty, there is the place where the thinker eager for knowledge ought to take up his station. He sees business, action; let things follow their own course, and is glad at success and failure. What is useful is only a part of what is significant. To possess a subject completely, to master it, one has to study the thing for its own sake. But whilst I am speaking of the highest and the last, to which we raise ourselves only late in the day by dint of frequent and fruitful observation, I see the boys before me: to them matters sound quite differently. The child might easily grasp every species of activity, because everything looks easy that is excellently performed. Every beginning is difficult! That may be true in a certain sense, but more generally one can say that the beginning of everything is easy, and the last stages are ascended with most difficulty and most rarely.”

Wilhelm, who in the meantime had been thinking, said to Montan, “Have you really adopted the persuasion that the collective forms of activity have to be separated in precept as well as in practice?”

“I know no other or better plan,” replied the former. “Whatever man would achieve, must loose itself from him like a second self; and how could that be possible if his Edition: current; Page: [21] first self were not entirely penetrated therewith?”

“But yet a many-sided culture has been held to be advantageous and necessary.”

“It may be so, too, in its proper time,” answered the other. “Many-sidedness prepares, in point of fact, only the element in which the one-sided man can work, who just at this time has room enough given him. Yes, now is the time for the one-sided; well for him who comprehends it, and who works for himself and others in this mind. In certain things it is understood thoroughly and at once. Practise till you are an able violinist, and be assured that the director will have pleasure in assigning you a place in the orchestra. Make an instrument of yourself, and wait and see what sort of place humanity will kindly grant you in universal life. Let us break off. Whoso will not believe, let him follow his own path: he too will succeed sometimes; but I say it is needful everywhere to serve from the ranks upwards. To limit one’s self to a handicraft is the best. For the narrowest heads it is always a craft; for the better ones an art; and the best, when he does one thing, does everything—or, to be less paradoxical, in the one thing, which he does rightly, he beholds the semblance of everything that is rightly done.”

This conversation, which we only reproduce sketchily, lasted until sunset, which glorious as it was, yet led the company to consider where they would spend the night.

“I should not know how to bring you under cover,” said Fitz; “but if you care to sit or lie down for the night in a warm place at a good old charcoal-burner’s, you will be welcome.”

And so they all followed him through strange paths to a quiet spot, where anyone would soon have felt at home.

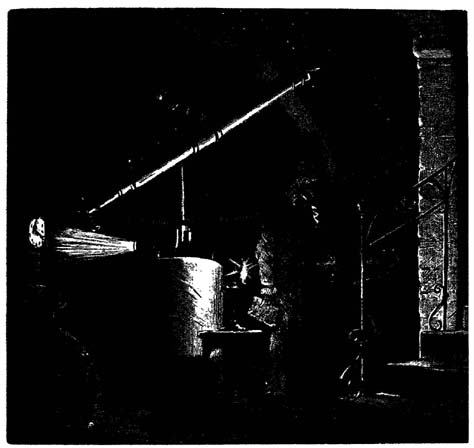

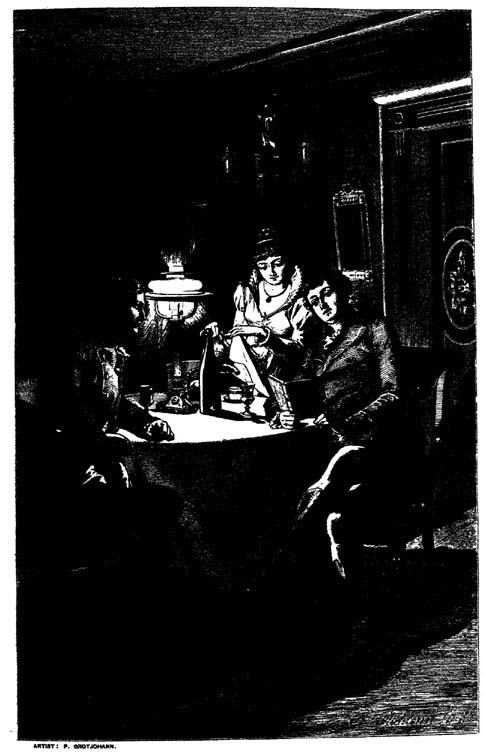

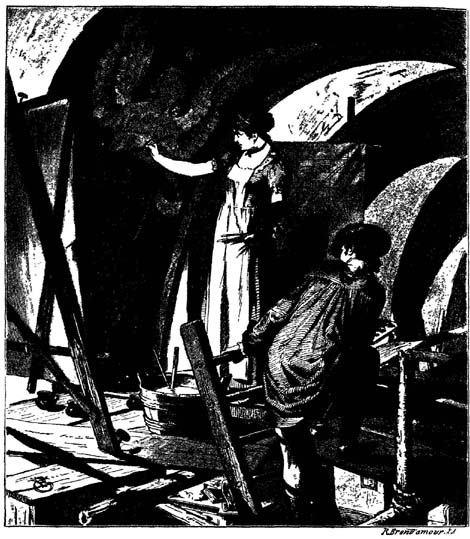

In the midst of a narrow clearing in the forest there lay smoking and full of heat the round-roofed charcoal kilns, on one side the hut of pine-boughs, and a bright fire close by. They sat down and made themselves comfortable; the children at once busy helping the charcoal-burner’s wife, who, with hospitable anxiety, was getting ready some slices of bread, toasted with butter so as to let them be filled and soaked with it, which afforded deliciously oily morsels to their hungry appetites.

Presently, whilst the boys were playing at hide-and-seek among the dimly-lighted pine stems, howling like wolves and barking like Edition: current; Page: [22] dogs, in such a way that even a courageous wayfarer might well have been frightened by it, the friends talked confidentially about their circumstances.

But now, to the peculiar duties of the Renunciants appertained also this, that on meeting they must speak neither of the past nor the future, but only occupy themselves with the present.

Jarno, who had his mind full of mining undertakings, and of all the knowledge and capabilities that they required, enthusiastically explained to Wilhelm, with the utmost exactitude and thoroughness, all that he promised himself in both hemispheres from such knowledge and capacities; of which, however, his friend, who always sought for the true treasure in the human heart alone, could hardly form any idea, but rather answered at last with a laugh:

“Thus you stand in contradiction with yourself, when beginning only in advanced years to meddle with what one ought to be instructed in from youth up.”

“Not at all,” replied the other; “for it is precisely this, that I was educated in my childhood at a kind uncle’s, a mining officer of consequence, that I grew up with the miner’s children, and with them used to swim little bark boats down the draining channel of the mine, that has led me back into this circle wherein I now feel myself again happy and contented. This charcoal smoke can hardly agree with you as with me, who from childhood up have been accustomed to swallow it as incense. I have essayed a great deal in the world, and always found the same: in habit lies the only satisfaction of man; even the unpleasant, to which we have accustomed ourselves, we miss with regret. I was once troubled a very long time with a wound that would not heal, and when at last I recovered, it was most unpleasant to me when the surgeon remained away and no longer dressed it, and no longer took breakfast with me.”

“But I should like, however,” replied Wilhelm, “to impart to my son a freer survey of the world than any limited handicraft can give. Circumscribe man as you will, for all that he will at last look about himself in his time, and how can he understand it all, if he does not in some degree know what has preceded him. And would he not enter every grocer’s shop with astonishment if he had no idea of the countries whence these indispensable rarities have come to him?”

“What does it matter?” replied Jarno; “let him read the newspapers like every Philistine, and drink coffee like every old woman. But still, if you cannot leave it alone, and are so bent upon perfect culture, I do not understand how you can be so blind, how you need search any longer, how you fail to see that you are in the immediate neighborhood of an excellent educational institution.”

“In the neighborhood?” said Wilhelm, shaking his head.

“Certainly,” replied the other; “what do you see here?”

“Where?”

“Here, just before your nose!” Jarno stretched out his forefinger, and exclaimed impatiently: “What is that?”

“Well then,” said Wilhelm, “a charcoal-kiln; but what has that to do with it?”

“Good, at last! a charcoal-kiln. How do they proceed to erect it?”

“They place logs one on top of the other.”

“When that is done, what happens next?”

“As it seems to me,” said Wilhelm, “you want to pay me a compliment in Socratic fashion—to make me understand, to make me acknowledge, that I am extremely absurd and thick-headed.”

“Not at all,” replied Jarno; “continue, my friend, to answer to the point. So, what happens then, when the orderly pile of wood has been arranged solidly yet lightly?”

“Why, they set fire to it.”

“And when it is thoroughly alight, when the flame bursts forth from every crevice, what happens?—do they let it burn on?”

“Not at all. They cover up the flames, which keep breaking out again and again, with turf and earth, with coal-dust, and anything else at hand.”

“To quench them?”

“Not at all: to damp them down.”

“And thus they leave it just as much air as is necessary, that all may be penetrated with the glow, so that all ferments aright. Then every crevice is shut, every outlet prevented; so that the whole by degrees is extinguished in itself, carbonized, cooled down, finally taken out separately, as marketable ware, forwarded to farrier and locksmith, to baker and cook; and when it has served sufficiently for the profit and edification of dear Christendom, is employed in the form of ashes by washerwomen and soapboilers.”

Edition: current; Page: [23]“Well,” replied Wilhelm, laughing, “what have you in view in reference to this comparison?”

“That is not difficult to say,” replied Jarno. “I look upon myself as an old basket of excellent beech charcoal; but in addition I allow myself the privilege of burning only for my own sake; whence also I appear very strange to people.”

“And me,” said Wilhelm; “how will you treat me?”

“At the present moment,” said Jarno, “I look on you as a pilgrim’s staff, which has the wonderful property of sprouting in every corner in which it is put, but never taking root. Now draw out the comparison further for yourself, and learn to understand why neither forester nor gardener, neither charcoal-burner nor joiner, nor any other craftsman, knows how to make anything of you.”

Whilst they were talking thus, Wilhelm, I do not know for what purpose, drew something out of his bosom which looked half like a pocketbook and half like a case, and which was claimed by Montan as an old acquaintance. Our friend did not deny that he carried it about like a kind of fetish, from the superstition that his fate, in a certain measure, depended thereon.

But what it was we would wish at this point not to confide as yet to the reader; but we may say thus much: that it led to a conversation, the final result of which was that Wilhelm confessed how he had long ago been inclined to devote himself to a certain special profession, an art of quite peculiar usefulness, provided that Montan would use his influence with the guild-brethren, in order that the most burdensome of all conditions of their life, that of not tarrying more than three days in one spot, might be dispensed with as soon as possible, and that for the attainment of his purpose, it might be allowed him to dwell here or there as might please himself. This Montan promised to do, after the other had solemnly promised himself unceasingly to pursue the aim which he had confidentially avowed, and to hold most faithfully to the purpose which he had once taken up.

Talking seriously of all this, and continually replying to one another, they had left their night’s lodgings, where a wonderfully suspicious company had by degrees gathered together, and by daybreak had got outside the wood on to an open space upon which they found some game, at which Felix particularly, who looked on delightedly, was very glad. They now prepared to separate; for here the paths led towards different points of the compass. Fitz was now questioned about the different directions, but he seemed absent, and, contrary to his usual habit, he gave confused answers.

“You are nothing but a rogue,” said Jarno; “you knew all of those men, last night, who came and sat down about us. There were woodcutters and miners, they might pass; but the later ones I take to be smugglers and poachers, and the tall one, the very last, who kept writing figures in the sand, and whom the others treated with a certain respect, was surely a treasure-digger, with whom you are secretly in concert.”

“They are all good people,” Fitz thereupon remarked, “who live poorly, and if they sometimes do what others forbid, they are just poor devils, who must give themselves some liberty, only to live.”

In point of fact, however, the little rogue, when he noticed the preparations of the friends to separate, became thoughtful. He mused quietly for a time, for he was in doubt as to which of the parties he should follow. He reckoned up his prospects: father and son were liberal with their silver, but Jarno rather with gold; he thought it the best plan not to leave him. Accordingly, he at once seized an opportunity that offered, when at parting Jarno said to him: “Now, when I come to St. Joseph’s I shall see whether you are honest: I shall look for the cross-stone and the ruined altar.”

“You will not find anything,” said Fitz, “and all the same I shall be honest; the stone is from there, but I have taken away all the pieces, and stored them up here. It is a valuable stone; without it no treasure can be dug up. For a little piece they pay me a great deal. You were quite right; this is how I came to be acquainted with the tall man.”

Now there were fresh deliberations. Fitz bound himself to Jarno, for an additional ducat, to get at a moderate distance a large piece of this rare mineral, on which account he advised them not to walk to the Giants’ Castle; but, however, since Felix insisted on it, he admonished the guide not to take the travellers too deep into the region, for no one would ever be able to find his way out again from those caverns and abysses.

They separated, and Fitz promised to meet Edition: current; Page: [24] them again, in good time, in the halls of the Giants’ Castle.

The guide walked ahead, the two others followed; the former, however, had scarcely ascended a certain distance up the mountain, when Felix observed that they were not walking on the path which Fitz had indicated.

The messenger replied, however: “I ought to know it better; for just these last few days a violent tempest has knocked down the next stretch of wood; the trees thrown one across the other obstruct this path. Follow me; I will bring you safely to the spot.”

Felix shortened the difficulty of the road by lively strides and jumps from rock to rock, and rejoiced at the knowledge he had gained, that he was actually jumping from granite to granite.

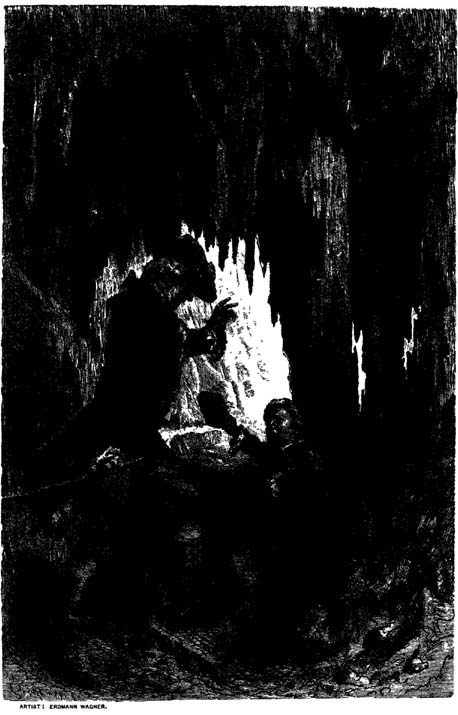

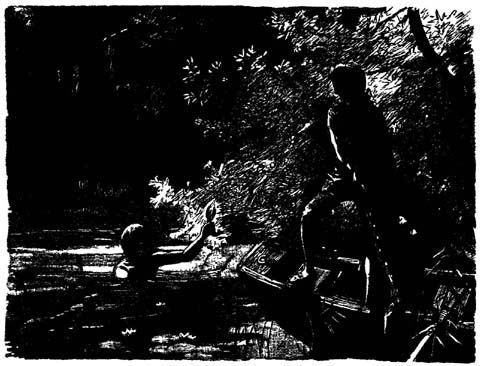

And so they went upwards, until he at last stopped short upon some black ruined columns, and all at once beheld before his eye the Giants’ Castle. Pillared walls stood out upon a solitary peak. Rows of connected columns formed doors within doors, aisles beyond aisles. The guide earnestly warned them not to lose themselves in the interior; and noticing at a sunny spot, commanding a wide view, traces of ashes left by his predecessors, he busied himself in keeping up a crackling fire. He was accustomed to prepare a frugal meal at spots of this kind, and whilst Wilhelm was seeking more correct information concerning the boundless prospect, Felix had disappeared; he must have lost himself within the cavern; he did not answer their shouting and whistling, and he did not appear again.

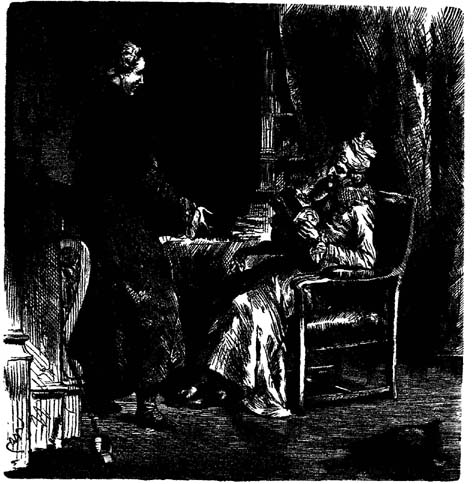

But Wilhelm, who, as beseems a pilgrim, was prepared against various accidents, took out of his hunting-wallet a ball of string, carefully tied it fast, and confided himself to this guiding clue, by which he had already formed the intention of taking his son into the interior. Thus he advanced, and from time to time blew his whistle, but for a time in vain. But at last there resounded from the depths a shrill whistle, and soon after Felix looked out on the ground from a cleft in the black rock.

“Are you alone?” whispered the boy, cautiously.

“Quite alone,” replied the father.

“Give me some logs of wood! give me some sticks!” said the boy; and, on receiving them, disappeared, first exclaiming anxiously, “Let nobody into the cave!”

But after a time he emerged again, and asked for a still longer and stronger piece of wood. His father waited anxiously for the solution of this riddle. At last the bold fellow arose quickly from out of the cleft, and brought out a little casket not bigger than a small octavo volume, of handsome antique appearance; it seemed to be of gold, adorned with enamel.

“Hide it, father, and let no one see it!”

Thereupon he hastily told how, from a mysterious inner impulse, he had crept into the cleft, and found underneath a dimlylighted space. In it there stood, he said, a large iron chest, not indeed locked, but the lid of which he could not raise, and indeed could hardly move. It was for the sake of mastering this that he had asked for the wood, partly to place them as supports under the lid, and partly to push them as wedges between; finally, he had found the box empty, save in one corner of it the ornamented little book. About this they mutually promised profound secrecy.

Noon was past; they had partaken of some food; Fitz had not yet come as he had promised; but Felix was particularly restless, longing to get away from the spot in which the treasure seemed exposed to earthly or unearthly claim. The columns seemed to him blacker, and the caverns still deeper. A secret had been laid upon him: a possession—lawful or unlawful? safe or unsafe? Impatience drove him from the spot; he thought that he should get rid of his anxiety by changing his locality.

They entered upon the road leading to those extensive possessions of the great landowner, of whose riches and eccentricities they had been told so much. Felix no longer leaped about as in the morning, and all three for hours walked silently on. Sometimes he wished to see the little casket, but his father, pointing to the porter, bade him be quiet. Now he was full of anxiety that Fitz should come. Then again he was afraid of the rogue; now he would whistle to give a signal, then again he would repent having done it; and so his wavering continued until Fitz at last made his whistle heard in the distance. He excused his own absence from the Giants’ Castle: he had been belated with Jarno; want of breath had hindered him. Then he inquired minutely how they had got on among the columns and the caves—how deep they had penetrated. Felix, half in bravado, half in embarrassment, told him one tale after another; he looked Edition: current; Page: [c] Edition: current; Page: [d] Edition: current; Page: [e] Edition: current; Page: [f] Edition: current; Page: [25] smilingly at his father, pinched him by stealth, and did all that was possible to make it clear that he had a secret, and was feigning.

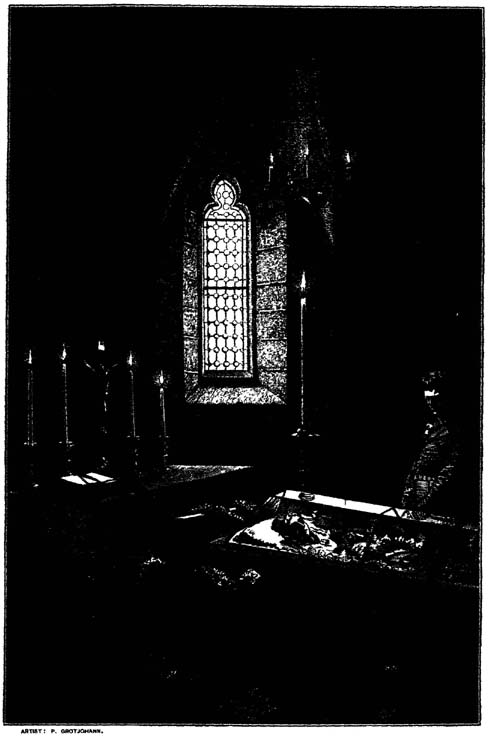

WILHELM AND FELIX IN THE CAVE.