Tags

Alan Bennett, Anne Bolyn, Brian Moynahan, Henry VIII, John Wycliffe, Sir Thomas More, The English Bible, Thomas Bilney, Tyndale's Burning, Use of Language, William Shakespeare, William Tyndale

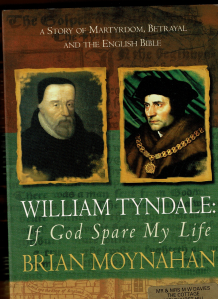

My husband’s recent re-ordering of our modest library led me to rediscover this powerful book by Brian Moynahan about religious intolerance and the brave man who translated the word of God into English.

Moynahan’s heart-stopping biography of the young Gloucestershire tutor forced to flee England in 1524 in order to safely translate the Bible into English is as much thriller as history. It brims with exhumations, double-agents, whispered confidences, poisoned soup and brutal burnings. There are unfamiliar glimpses of Anne Boleyn alongside the familiar autocratic ones of Henry VIII. Sir Thomas More, sadly, does not come out of it well. Indeed, it is less familiar figures like Thomas Bilney, who show unimaginable heroism. It is not an easy read. There is faith. Hope. But scant charity.

The agents of Tudor England caught up with Tyndale in the end. On the 6th October 1536, in Vilvoorde, just outside Brussels, he was bound to a stake with iron chains, with a noose around his neck. In the brief period he was allowed to pray, Foxe tells us he cried out in a loud voice: ‘Lord, open the King of England’s eyes.’ He was then strangled and burned, although it is said he was still living as the flames engulfed him. His executioner was instructed to add fuel to the flames until the body was utterly consumed, after which even the ashes were disposed of (probably in the nearby River Zenne) to obliterate any traces that might remain. His words, however, will surely survive as long as we have the English language. His prose has enriched the work of writers from William Shakespeare to Alan Bennett and has lessons even for stumbling novices like myself.

Tyndale’s unique contribution was that he was translating the Bible into English for the first time from the original texts in Greek and Hebrew. Moynahan ‘s biography makes particular mention of his use of verbs: ‘…he wrote at the infancy of the written language [for] it was common for people to read aloud, even when alone; and it is this habit, and Tyndale’s studies in rhetoric at Oxford, that accounts…for the charm and thunder that soar from the English Bible when it is spoken from the lectern.’ [Tyndale uses] ‘verbs where less flowing writers use nouns and adjectives…creating a cadence and sense of immediacy.’

This terrific book is still available, though now only on eBay or through specialist bookshops. It is not the easiest of reads, but it is rich with lessons, not only for those seeking to know how even the ‘boy that driveth the plough‘ came to have first-hand access to the Bible, but for those striving to write prose with a powerful punch. We must follow Tyndale’s example: short words; short sentences, and, above all, those potent verbs.

This Friday will mark 481 years since Tyndale’s death. What better time to remember a brave and gifted man, and everything we English-speakers owe him.

I’ve often admired the fine statue of him on the Embankment in London – see https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:William_Tyndale_Victoria_Embankment_Gardens.jpg I also learn from Wikipedia that there’s a monument to him atop a hill in Gloucestershire – see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tyndale_Monument

I’m embarrassed not to have known about this, especially as I commuted into London for many years and regularly walked through the Embankment Gardens on my way to Parliament Square. My next visit to London will warrant a detour.