Henry Ford, it seems, was a bit of a Fanboy …

One of Henry Ford’s first jobs was as an electrical engineer for the Detroit Edison Illuminating Company, which ran the electrical systems in the city. Ford, who was 13 years younger than the famous “Wizard of Menlo Park”, was at this time an unknown worker bee—who happened to be spending his spare time working on a “horseless carriage” that he called the Quadricycle. And although they never saw each other, the young Ford idolized Thomas Edison.

In 1896, Ford finally got the chance to meet his hero in person, when he was invited by his supervisor to attend the Edison Company’s annual convention. Of course Edison was also there, and Ford managed to sneak a couple of surreptitious photographs of his hero. And then, somehow, word got to Edison that Ford was working on an automobile, and he asked to see the young engineer. According to Ford’s later recollections, Edison asked him a number of technical questions, then, delighted, pounded on the table and advised Ford to “Keep at it!”

Ford did keep at it, and by 1905 his Ford Motor Company had made him one of the richest men in America. And then he approached his boyhood hero Edison with a business proposal: Ford would make an electric car, and Edison would make the batteries for it.

As a business deal, the plan was a failure: none of the various batteries that Edison came up with were suitable. But as a personal connection, the partnership proved to be priceless. Edison was by nature a private man who kept to himself and did not like close relationships, at least partly because he was afraid of everyone constantly asking him for money. But flivver king Henry Ford was already rich and didn’t need anything from Edison, and the older man felt able to let his guard come down. The two began corresponding, then meeting, and soon became close friends.

In 1885, Edison was already searching for a good place for a winter vacation home. At this time, Henry Flagler’s railroads were just beginning to reach Florida: the Sunshine state was secluded and remote, a quiet backwater that was attractive for its year-round nice weather and its neo-tropical birds and palm trees. It was just what Edison was looking for. In the tiny little village of Fort Myers (population less than 400), he would be able to relax in the sun and escape the bustle and pressures of his New Jersey lab. He purchased a tract of 13 acres along the Caloosahatchee River and sketched out a plan for a two-story bungalow, which was completed the next year. In their first winter there in 1886, Edison’s wife Mina planted an extensive garden, and the river offered swimming, boating, and fishing. The estate became known as “Seminole Lodge”. Over the years, during Edison’s annual winter visits, the lodge hosted a string of distinguished guests, including President-elect Herbert Hoover.

And another visitor was Henry Ford, who vacationed at Seminole Lodge in 1913, and then began making annual trips to Fort Myers to stay with Edison. Often another wealthy industrialist friend also joined them at the Seminole Lodge, tire magnate Harvey Firestone.

Thanks to Henry Ford’s Model T, the automobile had replaced the horse cart as the standard mode of transportation. It also introduced a new leisure pasttime– “caravanning”. The United States, with its huge open areas, was prime turf for car traveling, and among the early auto-camping enthusiasts were Ford, Edison and Firestone. In 1913, they formed a club which they called the Vagabonds, and went on long cross-country camping trips using Ford Lincoln trucks that had been turned into sleepers and mobile kitchens. The three were sometimes accompanied by President Warren G Harding or by nature writer John Burroughs. (They also had a staff of cooks, servants, chauffeurs and butlers traveling with them, so they were not exactly “roughing it”.)

Ford and Edison, meanwhile, had already become neighbors in Florida. In 1916, the bungalow next door to Edison’s estate, owned by New York businessman Robert Smith, went up for sale, and Ford seized the chance to be near his friend. He purchased the 7-acre lot, named it “The Mangoes”, and began spending winters there. The two would share annual winter vacations for the next 15 years.

By the time Edison reached his 80s, however, he was suffering from failing health. When he was confined to a wheelchair, his friend Ford responded by buying a wheelchair for himself, and challenging Edison to races. But Edison continued to fade, and by October 1931 it was apparent that the end was near. Henry Ford was unable to be with his friend, however, and when Thomas Edison died on October 18, he was accompanied only by a physician and by his son Charles Edison.

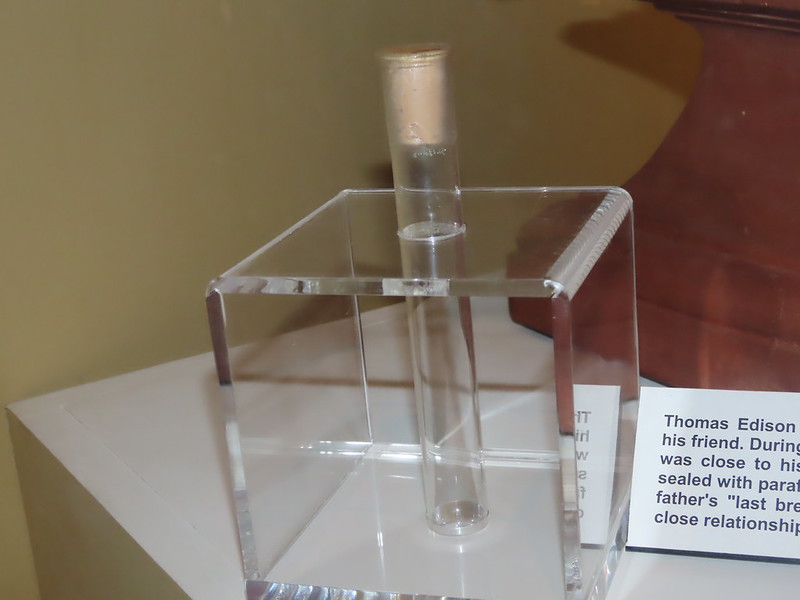

But, in an odd way, Ford was able to share his mentor Edison’s last moments anyway. As Thomas Edison lay on his deathbed, Charles Edison noticed a rack full of empty test tubes setting on a nearby shelf, and got an idea. So when the inventor gasped out his final breath, Charles leaned over, held several of the test tubes under the dying man’s nose, and captured Thomas Edison’s last breath—sealing it in with plugs of melted paraffin wax. And, as a gesture to signify the lifelong friendship the two had, Charles gifted one of the test tubes to Henry Ford. He kept it for the rest of his own life.

Today, that test tube is on display at the Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation in Dearborn MI. Also on display is Edison’s entire Menlo Park laboratory, which Ford dismantled, shipped to Michigan, and reassembled at his museum.