Pyrus pyrifolia

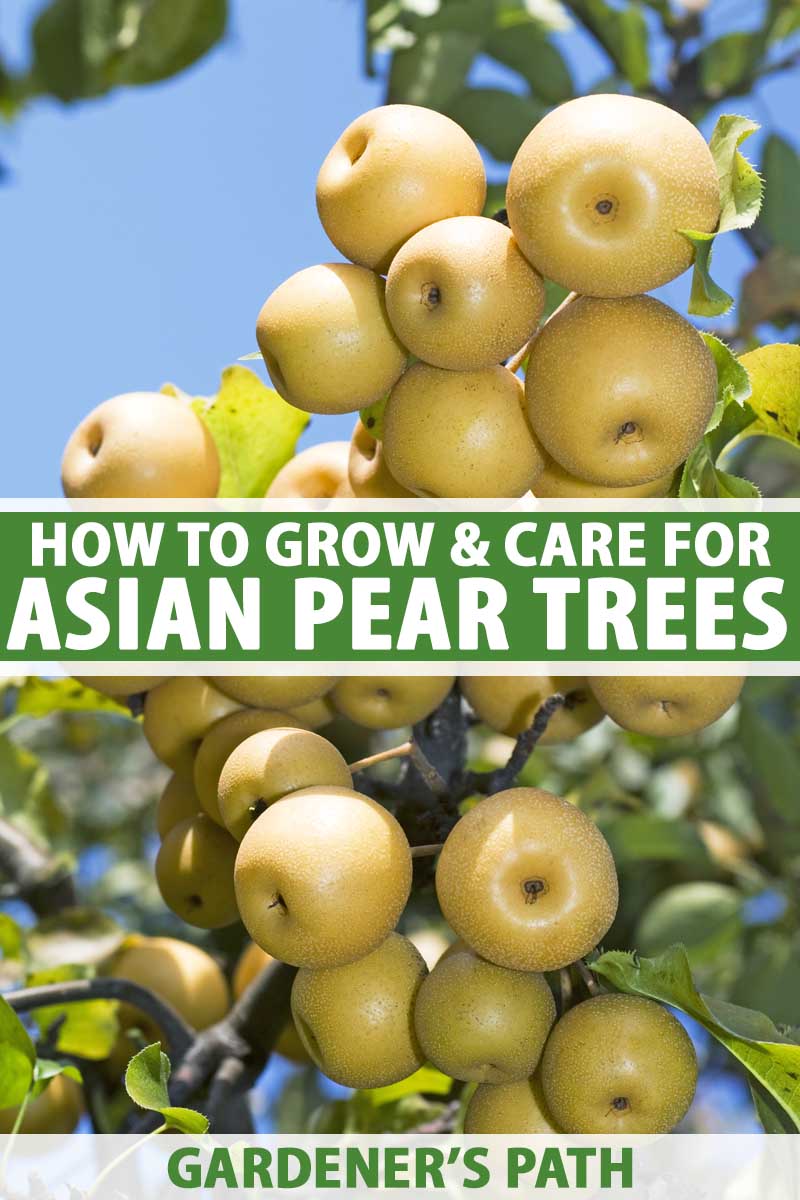

Maybe you know them as apple pears, papples, or nashi pears, but whatever you call them, the fruits of the Pyrus pyrifolia tree are delicious.

Juicy or crunchy (depending on the variety and maturity), honey-sweet yet not overpowering, mature Asian pears can be enjoyed right away when you pick them. Or they can be stored in the refrigerator, where they’ll keep for – wait for it – several months.

Often round like an apple, some P. pyrifolia cultivars are teardrop-shaped like their European counterparts.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

They can be hard to find at your local grocery store or farmers market in some places, but luckily, if you live in USDA Hardiness Zones 5-9, you can try your hand at growing them at home.

Even if you don’t have a large yard, you can still grow P. pyrifolia: some cultivars can grow up to 40 feet tall, but widely available dwarf varieties reach just six to 15 feet in height.

Are you ready to find out how to grow and care for your own Asian pear trees?

Here’s what I’ll cover:

What You’ll Learn

What Are Asian Pears?

Like apple, nectarine, and peach trees, Asian pears are members of the rose or Rosaceae family. They are also sometimes called P. serotina.

To set fruit, these deciduous trees require around 300-500 chill hours at temperatures lower than 45°F each winter, which isn’t too hard to achieve even in the warmer climates of Zone 8 or 9.

They blossom with fragrant white petals in the springtime and, depending on the cultivar and growing conditions, produce fruit four to seven months later. Asian pear trees can take between three to five years to begin producing fruit after propagation.

Like apples, each fruit contains five seeds. Unlike European pears (P. communis), Asian varieties don’t turn soft and mushy when ripe. They ripen on the tree and maintain a crisp, juicy texture.

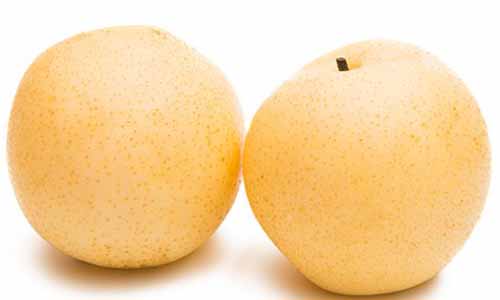

Asian pears are either round with greenish-yellow skin, round with bronze skin, or pear-shaped with green or brown skin, depending on the cultivar you are growing.

But they all have that delicious and enduring crunch that Bartletts can only dream of and that some of us prefer over the texture of a European pear.

Despite some cultivars producing fruit reminiscent of an apple, the Asian pear is not a hybrid with this fruit. Botanically, it is a true pear. I love it because I prefer firm and crisp varieties of this fruit, and if that’s your preference, you will too.

For best results, you will need to plant two varieties that bloom at the same time for pollination. Some cultivars, such as ‘Shinseiki,’ ‘20th Century,’ and ‘Tennosui,’ are self-pollinating.

Most other varieties require cross-pollination. Even in the case of self-pollinating cultivars, cross-pollination leads to much bigger harvests.

Pairings that work well together for pollination purposes are:

- Early-blooming ‘Shinseiki’ and ‘Yoinashi’

- Mid-blooming ‘Ichiban Nashi’ and ‘Shinsui’

- Late-blooming ‘Chojuro’ and ‘Hosui’

Asian pears can also cross-pollinate with European pears. Asian variety ‘20th Century,’ for example, blooms at about the same time as ‘Bartlett,’ and ‘Chojuro’ blooms with ‘Anjou.’

Planting a P. pyrifolia alongside a European variety can also encourage more honeybees flock to both trees, as they’re typically more attracted to European varieties.

Cultivation and History

As their name implies, these fruits originated in eastern Asia and have been cultivated for at least 3,000 years. More specifically, they’re native to western China, and long ago naturalized in south and central Japan.

Despite their long history in Asia, they’re relatively new in the United States, arriving here in 1820 when horticulturist William Prince imported the plant to grow in Flushing, New York.

Chinese miners and railroad workers planted seeds in California during the Gold Rush, and additional cultivars from Japan arrived with Japanese immigrants starting in the 1890s.

China, Korea, and Japan are the main commercial exporters of the fruit, but it’s also grown in the United States in California, Oregon, and Washington, thanks to those early immigrants.

High in Vitamins C and K, and rich in fiber, the crisp fruits are often sliced and added to salads, baked into pies, and enjoyed as snacks.

If you’re looking for an exciting fruit to grow at home that tastes like a pear but has the crunchy texture of an apple, look no further than P. pyrifolia.

Before you make your selections, make sure you’re in the right growing zone, and that you have plenty of space, and enough room to plant two varieties.

Propagation

As with many other types of fruit trees, P. pyrifolia are most often propagated by being grafted onto rootstock of another variety. This is because seeds don’t grow into exact replicas of their parent trees.

Because grafting takes skill and special equipment, the best way to plant an Asian pear tree is to purchase two varieties from a nursery or gardening store and find a perfect area to plant them together.

Other methods of propagation include micropropagation via tissue cultures.

Some adventurous gardeners try to root new trees from cuttings, but this has a 30-90 percent success rate under the most ideal conditions, in a professional greenhouse with controlled humidity and misting hoses.

Read more about pear propagation here.

How to Grow

If you’re growing trees grafted onto dwarf rootstock – aka dwarf cultivars of P. pyrifolia – you can plant them in containers. This is an excellent option for those with limited space.

Or, plant a dwarf or standard-sized cultivar straight into the ground for a beautiful and tasty addition to your landscape.

We’ll cover both planting methods to make it easy for you to choose which is best for your garden.

Planting in the Ground

The first thing you need to do before you bring your trees home in the spring or fall is to select the perfect location.

First, make sure you have enough space. The two trees will need to be planted about 15 feet apart if they’re dwarf varieties, and 30 feet apart if they’re full-sized cultivars.

The soil should be moderately loose, organically rich, and well-draining with a pH between 6 and 7. You can conduct a soil test to determine the pH and nutrient balance of your soil and amend accordingly.

The site should receive at least eight hours of full sun every day in Zones 5-7. If you live in Zones 8 or 9, select a site that receives partial afternoon shade to help temper the effect of the heat.

When you’re certain you have the perfect place for those saplings, place your order or bring them home and dig holes for the roots. Each hole will need to be the same depth as the root ball and twice as wide.

Place the root ball inside the hole and make sure the crown of the tree is level with the surface of the soil.

Backfill the hole with two parts native soil and one part well-rotted compost or manure, and water deeply.

Keep the soil moist until your area’s first wintertime freeze, especially in the sapling’s first few years of growth. To check the moisture level, stick your finger about one inch down into the soil. If it feels dry, give the tree a thorough watering.

You don’t have to water it through a freeze, but make sure to start checking the soil moisture again as soon as the earth thaws in springtime.

Planting in a Container

It’s easy to plant a dwarf tree in a container. Plus, it’s nice to have the option to move it from one place to another, especially if you live in Zones 8 or 9, where you have to make sure to keep your tree cool in the summertime. Container growing is also ideal for a patio or small backyard.

The most important consideration here, of course, is the size of your container.

It should be at least 20 inches in diameter. I love whiskey barrel containers for growing dwarf fruit trees, like this one from the Home Depot that’s 26 inches in diameter across the rim, 17.5 inches deep, and 21.5 inches wide at the base.

This size will give a dwarf tree some elbow room while making it (relatively) easy to move, most likely with help from a friend or by placing it on a cart with wheels.

Fill the container with gardening soil that’s one part topsoil, one part well-rotted compost, and one part peat moss.

Vermont Organics Raised Bed Recharge

Or make the task easy by filling it with premixed raised bed soil, like Vermont Organics Raised Bed Recharge available from the Home Depot.

Make a hole in the soil that’s as deep as the root ball and just a smidge wider. Set the root ball inside and backfill with soil, making sure the crown of the sapling is level with the soil surface.

Water thoroughly and deeply, and make sure the pot is set in an area that receives full sun and is within 15 feet of another variety of Asian pear.

You can add a three-inch layer of dark mulch to help keep the tree warm during the winter, and a light layer to help it keep cool during the summer.

Use organic mulch such as straw or wood chips so that the material can add nutrients to the soil as it decomposes. Replace it each season to keep that layer of protection over the tree’s root system.

Growing Tips

- Plant in rich, well-draining soil

- Choose a location with full sun or partial afternoon shade if you live in Zones 8 or 9

- Fertilize every spring with a 10-10-10 (NPK) fertilizer

Pruning and Maintenance

During the first year of growth after planting, you’ll want to water your Asian pear tree once or twice a week, depending on the amount of rainfall.

Give it a thorough soaking at the base, and let the top inch of soil dry out before you water again.

Once the tree is established, you can water it once a week, or when the top two to three inches of soil dry out.

Every time you water, check for weeds. You don’t want any weeds or grass growing over the root system and competing for water and nutrients.

To retain moisture and suppress weeds, consider putting down a three-inch layer of mulch. In warm areas, use a light-colored mulch to help keep the roots cool.

As for fertilizing, you only need to make sure the tree receives fertilizer once a year: as soon as the soil is workable in the spring.

Simply add a balanced 10-10-10 (NPK) fertilizer to give the plant a boost.

To keep the tree healthy, prune away diseased, broken, or injured branches during its winter dormancy period.

You can also prune the tops of the branches farthest away from the trunk, as those produce fruit that’s less sweet and often smaller. This will also help to keep the height manageable.

In addition, trim some of the branches nearest to the trunk to encourage them to produce blossoms. To do this, use pruning shears and cut the branch about two or three buds away from the main branch.

In all, you should prune about 10 percent of the tree’s total branches each winter.

If you are growing your Asian pear in a container, you’ll want to prune it to remain about five to six feet tall – essentially turning it into a fruit-bearing shrub rather than a fully dwarf-sized fruit tree. You’ll still get a decent harvest, but your tree will remain a manageable size.

Once the tree blossoms and begins fruiting in the spring, thin the fruits to one pear every four to six inches on any given branch.

This helps the individual fruits grow bigger and reduces pest and disease infestation since the space provides the fruits with adequate ventilation.

Cultivars to Select

Peruse our three favorite cultivars of this tasty fruit:

Chojuro

True to its name, which translates to “plentiful” in Japanese, ‘Chojuro’ produces ample fruit, often in its very first year after planting.

With its round apple shape and juicy-sweet butterscotch flavor, this variety is the one most commonly found in grocery stores (when you can find them!).

But you can have it in your own backyard, too. ‘Chojuro’ is a dwarf cultivar that grows to a mature height of eight to 10 feet with a spread of six to eight feet.

Easily pollinated by planting ‘Hosui’ alongside it, ‘Chojuro’ requires 450 chill hours.

You can find trees available from Nature Hills Nursery.

Hosui

Are you ready to dive headfirst into the world of growing P. pyrifolia? Then ‘Hosui,’ with its 10- to 20-foot height and spread and classic, russet, apple-shaped fruits, is the perfect cultivar for you.

In Japanese, ‘Hosui’ means “abundant juice” or “much water,” depending on the translation. You get the idea: this is a large, extra-juicy cultivar.

With 300-400 chill hours required each winter at 45°F or below, this is the perfect tree for those in cooler climes.

Although it grows well in warmer locations, keep in mind you won’t get a good harvest with fewer than 300 chill hours.

This cultivar often begins producing fruit in its second year, though it can take up six years before you can pick a decent harvest. Fruit tends to ripen in early August.

It’s also a self-pollinating variety, although you’ll only get a small harvest without planting another variety nearby with a similar bloom time for cross-pollination.

You can find bare root ‘Hosui’ trees available at Burpee.

If you prefer a dwarf ‘Hosui,’ which reaches up to 12 feet in height, you can find it at the Home Depot.

Shinseiki

‘Shinseiki,’ which translates to “new century,” is a cross between two popular varieties: ‘20th Century’ and ‘Chojuro.’ When ripe – usually sometime in August – this mid-size fruit is bright yellow and extremely crunchy.

With a mild flavor and coarse texture, this is the fruit for those of us who love firm pears with a hint of rose flavor.

‘Shinseiki’ reaches a height of 12 feet and only requires 250-300 chill hours.

Container trees are available at Nature Hills Nursery.

20th Century

‘20th Century,’ aka ‘Nijisseiki,’ is highly popular for its abundance of incredibly juicy fruit and ornamental, multi-season interest.

The attractive mid-sized fruit is bright yellow with a hint of rosy blush, and it has a crisp texture and mild flavor. A good keeper, fruits store well for up to five months in cold storage at 31°F.

Before the leaves appear, branches are covered in clusters of showy white blossoms. Fruit is ready to harvest starting in early August, and in autumn, the glossy green leaves turn a vibrant orangey red.

Trees reach mature dimensions of 12 to 18-feet-tall with a spread of 12 to 15 feet.

‘20th Century’ requires 400 chill hours at temperatures below 45°F. Although it is self-fertile, this type delivers a larger crop when planted in close proximity to another cultivar that blooms at the same time.

Container trees are available at Nature Hills Nursery.

Want More Options?

Be sure to check out our supplemental guide, “9 of the Best Asian Pear Varieties for the Home Garden” to find the best choice for your soil and climate.

Managing Pests and Disease

While P. pyrifolia don’t fall prey to too many pests or diseases, there are a few major troublemakers to watch out for.

Herbivores

If you have deer or moose in your area, it’s time to learn how to keep the large herbivores away from your precious Asian pear trees.

Moose and Deer

Cervids, whether they’re moose or deer, won’t hesitate to devour your tree whether it’s got fruit on it or not.

Trust me, I learned this the hard way.

But I also learned how to keep the pests out of my apple orchard, which you can learn more about in our guide to keeping moose out of your yard.

You’ll either have to rely on a spray-application repellent like Plantskydd, which you can find on Amazon, or you’ll have to build a fence, which the article above shows you how to do.

I do both. I don’t take any chances with Cervids.

Insects

There are two major plant pests to watch for when you’re growing Asian pears.

Codling Moth

The first is the codling moth (Carpocapsa pomonella), which eats through the fruit to get at the seeds, rendering it inedible. Codling moths lay tiny translucent eggs on the leaves. The larvae have black heads and white bodies.

If you happen to spot eggs or larvae before they do too much damage, you can try releasing moth egg parasites (Trichogramma spp.), available from Arbico Organics, according to package instructions.

BONIDE® All Seasons Horticultural Spray Oil

You can also spray horticultural oil, available from Arbico Organics, on the leaves and trunk to smother unhatched eggs.

Another way to prevent infestation is to space the fruits far enough apart so they aren’t touching, thinning them to one pear every four to six inches on any given branch.

Twospotted Spider Mite

The twospotted spider mite, Tetranychus urticae, is a tiny brownish-green pest that causes damage to foliage and usually only bothers a tree if it is water-stressed.

Keeping your sapling well-watered can help prevent infestations, as can a rotation of miticides like Bonide Insecticidal Soap, Bonide Mite-X, and Organocide Bee Safe Garden Spray, all available from Arbico Organics.

Diseases

There’s one major disease that threatens the health of your P. pyrifolia plants. Below, you’ll find out what it is and how to treat it.

Fire Blight

By far the most dreadful disease an Asian pear tree can face, fire blight, caused by the bacteria Erwinia amylovora, destroys any existing fruit and turns leaves to a burnt-crisp color and texture, hence the name.

It spreads easily and can kill entire trees. Early treatment is crucial to the recovery of a plant.

If you notice the telltale shriveled leaves, remove the entire affected branch at least 12 inches below the first infected leaf. Take it far away to be burned or dispose of it in the trash.

Dip your shears or pruners in a solution of water and 10 percent bleach to help prevent the spread of the infection.

BONIDE® Liquid Copper Fungicide

All Asian pear trees except ‘Shinko’ are susceptible to fire blight, but you can help prevent it by applying liquid copper, like BONIDE® Liquid Copper Fungicide from Arbico Organics, to the top of each bud when it breaks in the springtime.

Reapply the solution every four to five days until the blossom shrivels and the fruit begins to grow.

Harvesting

Fruits may be harvested any time between August and October, depending on the cultivar you’re growing.

Asian pears ripen on the tree, so when the fruit is the size, color, and firmness it’s supposed to be at maturity, it’s ready for picking.

If you think it’s almost picking time but you’re not sure, take one pear off the tree and bite into it. Does it taste like a delicious, crisp, juicy pear? If so, then it’s harvest time!

To harvest, gently grasp the fruit, lift it, and twist it off the branch. Pack your bounty in a padded bucket until you decide what to do with them, as they bruise very easily.

Preserving

The best way to preserve them to eat whole? Place them in the chiller compartment of your refrigerator. They’ll retain that irresistible crisp texture and flavor.

I doubt they’ll even last you three months, they’re so delicious.

You can learn more about how to store pears in our guide.

You can also dry slices in the oven. Start by washing each fruit, peeling the skin off (if you want to), and coring it. Cut into slices that are 1/2 an inch thick.

Lay the slices on a greased cookie sheet. Place the sheet in an oven heated to just 175°F and cook for about four hours, flipping the slices over every hour, until they have a leathery texture.

Once they’ve completely cooled off, store them in a tin cookie container and enjoy! They’ll last between six months and one year in a cool, dry location.

If you’d rather freeze your pears to puree later for smoothies or baking, you can do that too. Peel them, core them, and slice them into halves or into smaller pieces.

Lay the pieces on a cookie sheet and put them into the freezer for four hours or until they’re frozen solid. Transfer them to a freezer bag, and voila! Just remember to eat them within six months.

Recipes and Cooking Ideas

In my opinion, the best way to eat an Asian pear is fresh off the tree. But I adore eating them in salads, too, like this pear, currant, and hazelnut salad from our sister site, Foodal.

The recipe calls for ‘Bosc’ pears, which you can easily substitute with sliced P. pyrifolia.

If you have a sweet tooth, you could also use some of your crop to make this heavenly pear sorbet with ginger-infused maple syrup, also from Foodal.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Perennial fruit tree | Maintenance: | Moderate |

| Native to: | China, Korea, Japan | Tolerance: | Frost |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 5-9, depending on variety | Soil Type: | Fertile, rich in organic matter, loose |

| Season: | Spring-fall | Soil pH: | 6.0-7.0 |

| Exposure: | Full sun, part afternoon shade | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Time to Maturity: | 2-6 years | Companion Planting: | Other pear trees |

| Spacing: | 15-30 feet (depending on variety) | Attracts: | Bees, birds, flies, wasps, and other pollinators |

| Planting Depth: | Same as root ball | Order: | Rosales |

| Height: | 20-30 feet (8-12 dwarf) | Family: | Roseaceae |

| Spread: | 20-30 feet (8-12 dwarf) | Genus: | Pyrus |

| Water Needs: | Average | Species: | pyrifolia |

| Common Pests: | Aphids, codling moth, deer, moose, twospotted spider mites | Common Diseases: | Bacterial canker, crown rot, fire blight, powdery mildew |

A Peary Happy Harvest

I dream of traveling to Japan and China someday, to sample their expertly grown P. pyrifolia fruits. If you’ve ever had this experience, consider me jealous, but in a good way.

Have you ever grown Asian pear trees in your backyard? I’d love to hear your stories or questions in the comments section below.

And for more information about growing pear trees, check out these guides next:

I’ve just planted a chojuru and a Bartlett next to each other. Hope they take off in the spring! I’ll be sure to fence for deer soon…. ????

That should work well. Yes, do fence for deer or at least apply Plantskydd regularly! There’s nothing sadder than watching cervids snack on fruit trees. Best of luck!

Hi Laura thanks for al the tips and information. I have a hybrid Asian pear tree – where different branches have different variety of pear. There was some rot on it last year. Black spots on leaves and lots of insects. Will take care of it this year with your recommendations.

I’m glad this guide helped, Komal!

Can you make pear jelly from Asian pears? Thinking of planting a couple of trees, but want to be able to make jelly. If so, do you have any recipes on how to do this process?

I don’t see why you couldn’t. Any apple or pear jelly or butter recipe should work. Asian pears generally have an apple-like consistency rather than the more granular texture of canning pears. All of them usually contain lots of natural pectin but you might want to experiment a bit before discounting the need for store-bought pectin.

I live in Las Vegas, NV. My Asian pear tree, Shinseike variety, bears good fruit but is very hard and not crispy. I have a grass lawn with sprinklers to maintain it. What’s a possible solution to make fruit crispy?

Hi Art! When you say they are not crispy, do you mean they aren’t juicy and crunchy at the same time? Are they dry and hard?

Same here, my pears are hard. Even when waiting late to harvest in hopes of them getting a bit softer. It produces tons of fruit but it’s hard.

Are you waiting to pick until they’re fragrant, and more yellow than brown? The fruit should still be firm, but not too hard to eat or hard to the point where it’s lacking flavor and juiciness. These trees tend to produce more fruit than they can support, and thinning can improve the quality of your harvest.

Eating nashi in japan was a heavenly experience! Made me start my own pear orchard in my back yard. Learning as I go, but enjoying these fruits is a great reward for thr effort!

I bet it was–that experience is on my bucket list! Always feel free to reach out if you encounter any difficulties!

My Asian pear tree blooms and produces tiny marble-sized fruit that never develops. It only produced edible fruit once. What’s wrong?

Thinning is probably the answer, Annette. Trees will often produce more flowers and fruit than they can sustain to yield a uniformly high-quality harvest. Thinning early in the season to remove excess fruit growing close together will give what remains the space and resources to mature and ripen. Early in the season when the fruits are small, thinning to one pear per cluster or providing about 4-6 inches between each is recommended. Hope this yelps you to bring in a satisfying harvest next year! If this does not resolve the problem, look into the environmental conditions surrounding your tree –… Read more »

Thanks for such an informative website! I visited China in 2017 and enjoyed all sorts of different shaped Nashi fruit. One was especially interesting – small, plum-sized and aromatic. Since this sort is not sold in Europe I took the seeds with me and have about 10 trees in my garden. I know seeds do not give an exact parent, and indeed each tree looks quite different than its siblings. However – none of them bud, not one flower after all these years. Is there any way to encourage budding? someone gave me the advice I should purposely injure the… Read more »

Where are you located, Ethan? Winters that are too mild can lead to a failure to bloom and produce fruit, since these trees require a certain minimum number of chill hours each winter. If that’s not the culprit, I’d also consider the soil fertility and your fertilizing practices, as well as sun exposure and irrigation. Intentionally injuring the roots is not something I would recommend.

I recently purchased both a 20th century and Hosui from a nursery that carried Dave Wilson fruit trees. They are both on OHXF333 rootstock which says it can dwarf a tree a bit. My question is can these trees be kept in containers? Also, the 20th century seems to have put out leaves before blossoms – I’m starting to see many more popping out after there are a fair amount of leaves. Is that normal, will it set fruit? Thanks in advance!

Where are you located, Paul? Is it possible that they had already flowered before you brought them home? And do you mean you’re seeing “many more” leaves popping out, or it’s producing blooms after the leaves? Trees will sometimes leaf out without producing blooms if they’re grown beyond their recommended USDA Hardiness Zone, or if unusually harsh late winter/early spring conditions caused the buds to drop without opening. This type of rootstock is known as “semi-dwarfing,” so cultivars will usually grow to be about half to two-thirds of their standard size. But you’d still need very large containers, and the… Read more »

For the last three years most of the inch and a half pear stems have turned black and fallen off the tree. Suggestions?

If my tree is producing some fruit does that mean it is a self pollinator? It is about 12 years old but I do not know what variety it is. Do I need a second tree to help with pollination?

The tree gets covered with blooms. But as tiny little pears begin to develop, that’s when the stems just fall off en masse.

Where are you located, Randall, and do you thin the fruit after it begins to develop? That’s typically peak productive age for Asian pears. Trees that are growing in the wrong climate, or that lack the environmental resources (nutrients, water, sunlight, etc.) to sustain a healthy crop will drop fruit to put their energy elsewhere. It’s also much more difficult for a tree to sustain lots of fruits, but thinning will help to encourage the production of a more robust, higher quality harvest. Producing small fruits does mean pollination is occurring, though it could be insufficient. A pollinating partner that… Read more »