The sources and size of tax evasion in the United States

Overview

Tens of millions of Americans will duly pay the taxes they owe and file for their refunds by Tax Day in 2021, which was delayed until May 17. Meanwhile, some of the wealthiest Americans will engage in complicated tax evasion schemes that will cost the U.S. government $700 billion this year, according to U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen.

Tax evasion has reached such heights that the Biden administration is proposing bold measures to crack down on rich tax cheats. And academic research is leading the way in exposing the schemes and frauds that the rich use to evade taxes and how to close the so-called tax gap.

The tax gap is the difference between what taxpayers owe to the IRS and what is actually paid. Because unreported or hidden income cannot be directly observed, academic research is key in documenting the sources and size of the tax gap. For instance, Natasha Sarin, now at the U.S. Department of the Treasury, and Larry Summers at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government corroborate Secretary Yellen’s assertion that the tax gap is about $700 billion this year and outline many steps to close it.

This issue brief examines the following factors that help determine the size of the tax gap:

- The growth of economic inequality

- The availability of extralegal means to hide income from the IRS

- Falling IRS resources to investigation tax evasion and enforce tax laws

Understanding these sources of evasion can lead to strategies to close the tax gap.

Inequality fuels tax evasion

Growing income and wealth inequality in the United States over the past five decades has several serious implications for tax evasion. First, as inequality grows, the rich find more and more ways to hide their income (to pay for tax avoidance schemes, for instance) and also have more incentives to find ways to do so (more money to protect).

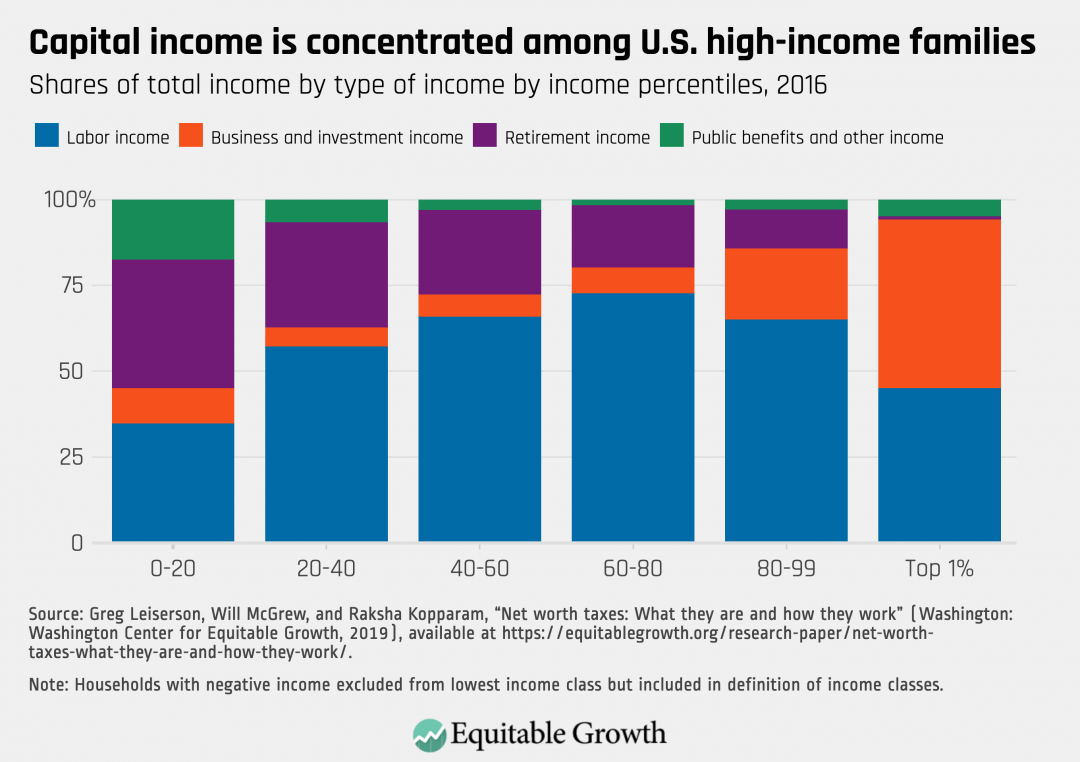

Second, the income earned by the top 1 percent is fundamentally different than the income most Americans earn. Most Americans earn income primarily from their wages and secondarily from retirement income and public benefits. These income sources are easily tracked and verified by the IRS. Meanwhile, the wealthy are more likely to gain income from their businesses or capital investments. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Business income and investment income is harder for the IRS to track because they often require taxpayers to self-report, which can be unreliable. In fact, a groundbreaking study by John Guyton and Patrick Langetieg of the IRS, Daniel Reck of the London School of Economics, Max Risch of Carnegie Mellon University, and Gabriel Zucman of the University of California, Berkeley shows that the top 1 percent of tax filers hide their income far more than was previously known. Using evidence from random IRS audits, a voluntary offshore asset disclosure program, and analysis of the structure of passthrough businesses, the co-authors show that the top 1 percent probably hide more than 20 percent, on average, of their income from tax collectors, accounting for 36 percent of the tax gap.

This research shows that in some ways, growing inequality is self-reinforcing. As resources become concentrated, those with these resources increasingly hide their income from scrutiny.

The rich use offshore accounts and business entities to hide taxable income

Tax noncompliance is driven by income that is not subject to third-party reporting. People report wage income, public benefits, and interest earned on savings accounts on their individual tax returns. These income sources are also separately reported to the IRS by their employers, by government agencies, and by financial institutions. This double reporting makes it very difficult for individuals to evade taxation on these sources of income. Consequently, tax compliance in these forms of income is quite high, and evasion is quite low.

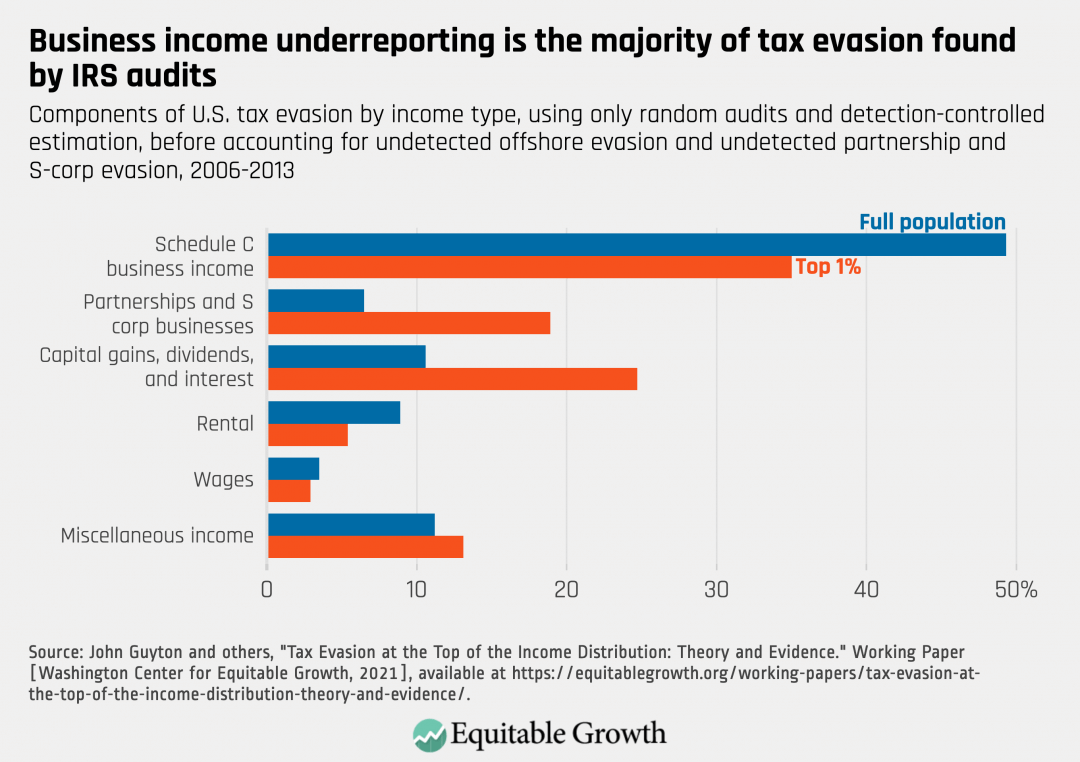

In contrast, tax evasion skyrockets when there is no third party reporting a flow of income to the IRS. This is very often the case for personal business income, overseas income, for some capital gains, and for some interest and dividends. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Again, the types of income which are most frequently misreported are also the types of income that are disproportionately common among the top 1 percent. Tax evasion at the top, however, is even more drastic than shown here. The five co-authors show that the very wealthy use two primary methods to avoid taxes—and avoid detection in the random audit data shown above. First, they place their capital gains, interest, and dividend income in offshore accounts to hide it from scrutiny by the IRS; foreign financial institutions have not historically been subject to the same reporting requirements as U.S. institutions. Second, they underreport income in their personal partnership and S-corporation businesses, which are difficult for the IRS to examine.

Partnership and S-corporation businesses differ from more traditional Schedule C businesses in their level of transparency. On tax forms, a Schedule C business can be attributed to a sole proprietor who reports her business’ profits, deductions, and expenses on her personal 1040 tax return. A partnership, however, reports its earnings separately from its owners, who only report their share of the profits or losses on their individual tax returns. This separation between business entity and owner creates technical and data hurdles for IRS auditors seeking to trace tax evasion.

Often, is it not possible to match partnership business income to personal income without great effort. A partnership business can have many owners, and indeed, they can be owned by other partnerships, sometimes creating a complex web of ownership. Research by Michael Cooper of the U.S. Treasury Department and his co-authors shows that 15 percent of partnership income was in circular partnership ownership patterns—partnerships owning other partnerships owning other partnerships—and, distressingly, almost 10 percent was not able to be linked to any individual’s tax return. Of the income that can be traced to individuals, two-thirds accrues to the top 1 percent.

The research on tax evasion firmly establishes that when streams of income are not subject to third-party reporting, the wealthy are able to hide their income from taxation. It also shows that the wealthy are constantly moving their income to escape IRS scrutiny. For instance:

- Rich investors will attempt to hide income in tax-haven countries so long as their banks will help them to hide this income. Financial institutions are key intermediaries in hiding money from tax collectors—for example, by concealing income under layers of business entities. Yet when new policies crack down on bank activities, would-be evaders cut down on their evasion, finds Jim Omartian at the University of Michigan.

- Around the 2008 financial crisis, many countries started signing data-sharing agreements to combat tax evasion. These one-by-one agreements allowed countries to see their citizens’ assets and income in foreign-based financial institutions for tax purposes. Research by Niels Johannesen of the University of Copenhagen and UC Berkeley’s Zucman found that this caused evaders to move funds to alternate tax-haven countries that did not sign these agreements.

- Enforcement initiatives by large countries such as the United States can have large effects on reducing evasion. Even smaller, targeted enforcement policies (as opposed to comprehensive ones) after 2008 increased offshore-income reporting by billions of dollars per year, find Johannesen, Langetieg, Reck, Risch, and Joel Slemrod of the University of Michigan.

- A comprehensive attempt to tackle evasion, such as the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act, could be expected to have larger effects. Indeed, an early look at the program by Lisa De Simone and Rebecca Lester of Stanford University and Kevin Markle of University of Iowa suggests FATCA is having large effects on tax evasion, though much more work needs to be done to counter new evasion opportunities.

Tax evasion is complex and requires both the closing of known loopholes, as well as dedicated resources for enforcers to keep pace with lawbreakers. Unfortunately, the tools to combat these crimes have been lacking in the past decade.

Enforcement resources have been declining

Academic research establishes that Secretary Yellen is right about the size of the tax gap and that given some tools, the IRS can meaningfully close this gap, increase equity, and pay for valuable investments in our society. The Treasury Department’s Sarin and Harvard’s Summers find that by “performing more audits (especially of high-income earners), increasing information reporting requirements, and investing in information technology,” the IRS could generate more than $1 trillion in revenue over a decade—even more than the Biden administration projects it can raise.

These two tools—more audits and more reporting requirements—are necessary and work in tandem: Greater IRS enforcement budgets and greater access to information on income flows will cut evasion.

After a decade of budget cuts, the IRS has lost more than 15,000 enforcement staff since 2010. With more resources, such as the $80 billion that the Biden administration proposes to invest in the agency, the IRS will be able to better litigate tax disputes and conduct more and better audits of the top 1 percent, who now experience audits almost as often as low-income recipients of the Earned Income Tax Credit. The debilitating defunding of the IRS has allowed tax evasion to proliferate, degraded service for regular taxpayers, and made our tax system more regressive.

Congress has stepped up, but it could do more. In addition to Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act, which can help target unreported overseas income, the American Rescue Plan included a provision requiring companies that use independent contractors, such as gig companies, to increase third-party reporting of payments to the IRS. This will increase the double reporting that research shows is necessary to enforce tax laws, cutting down on evasion through business entities, while FATCA makes it harder to hide income overseas. Other recent legislation may make it easier to track who ultimately owns a partnership businesses.

The IRS, however, still needs more tools to combat tax evasion, and Congress can still do more to increase third-party reporting to the IRS. And, of course, any enhanced reporting is of limited use unless the IRS has the staff to process the new data it collects. So, this Tax Day, Congress should make it a priority to increase resources for the IRS and make the tax system more equitable and fair by making tax cheating more difficult.