A platform for posting anonymous comments tied to

a location, the increasingly popular Yik Yak has built-in privacy

settings that prevent it from being used around high schools.

What’s your Yakarma score?

Josh Ilori, a sophomore economics major, earned a respectable 315. Adam Sokolski, a junior history and education major, has an impressive 1952. I, however, rock a measly 113.

Yakarma has entered into the campus lexicon with the new social networking app Yik Yak. The app, aimed at college campuses, is a hyperlocal live feed of anonymous messages. Yik Yak, which has been described as a “virtual bulletin board,” gained more than 100,000 users in three months, mostly on Southeast and East Coast college campuses, according to TechCrunch.

The app’s popularity has extended to this university. One look at a Yik Yak feed on campus shows students are plugged into the latest craze, often engaging in commentary on campus news such as pedestrian safety on Route 1 or the latest happenings at Stamp Student Union (including outrage over Chick-fil-A running out of chicken).

The messages on Yik Yak vary from funny to vulgar (but still funny) to downright cruel personal attacks against individuals. Users can express approval or disapproval on comments by upvoting or downvoting. “Yaks” with the most upvotes will appear in the app’s “Hot” tab.

My enjoyment of Yik Yak comes from finding other students I can relate to. A post expressing that amazing feeling of closing all your tabs after finishing an assignment? Upvote. A comment venting about students who refuse to walk on the right side of the sidewalk? Upvote. A Yak expressing a love of Netflix? Definite upvote.

“I think it’s dumb, but it’s incredibly funny and entertaining,” Ilori said.

Ilori describes his Yakarma score as “terrible” (which must make mine absolutely embarrassing) but explains he mostly uses the app to pass the time, whether he is on the bus or in the bathroom.

Ilori says he posts “maybe once or twice a week” about topics such as the weather in College Park or the Washington Wizards, which get a few upvotes, a sign Ilori’s peers agree with his statements.

Sokolski posts Yaks more often but infrequently. He can go a week without posting, followed by a litany of posts that tend to get a lot of upvotes.

“I think it’s pretty fun,” he said. “It’s pretty addicting, too. You want to keep your score up. You feel cool when you get a lot of upvotes on something.”

As a source for campus news, Yik Yak can effectively update users on university affairs and offer a channel for student commentary. Illori said he learned of a pedestrian death on Route 1 and the North Campus power outage through the app.

But Sokolski cautions students not to take the app too seriously.

“A lot of stuff on there, people make up,” he said. “People just try to stir things up.”

Yik Yak recently drummed up controversy about the app being used as a platform for cyberbullying because users can remain anonymous.

FOX10 News in Alabama reported a teenager was arrested for threatening to shoot someone in a post on the app, and a number of anonymous bomb threats caused lockdowns for two schools in California, according to the Los Angeles Times. Additionally, Yik Yak users in Chicago reportedly bullied a girl for getting raped, according to WLS-TV (ABC 7 Chicago). Yikes.

“Untruthful, mean, character-assassinating short messages are immediately seen by all users in a specific geographic area,” wrote psychiatrist Dr. Keith Ablow in an op-ed for Fox News. “Yik Yak removes all pretense of being a person with empathy, genuinely connected to other human beings.”

According to the Chicago Tribune, at least four schools sent out warnings to parents about Yik Yak, and some school districts have banned the use of the app, although there is no way of regulating students’ access to the app. Yik Yak disabled its service in the Chicago area.

Sokolski said it makes sense that schools have banned the app, given he has seen “people hating on each other” and “individual people getting called out.”

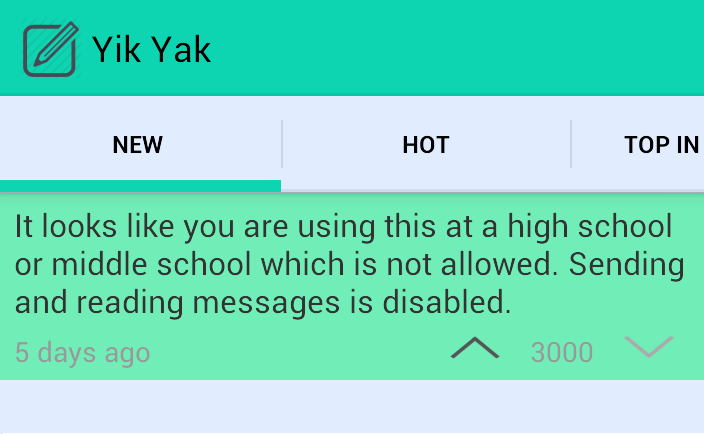

But the founders have taken an important step in protecting the app’s users. They decided to block middle and high school users from the app by disabling use near or on school grounds.

“One of the things we were planning to do is to essentially geo-sense every high school and middle school in America,” Brooks Buffington, one of Yik Yak’s co-founders, recently told CNN. “So if they try to open the app in their school, it will say something like ‘no, no, no, looks like you are trying to open the app on a high school or middle school, and this is only for college kids,’ and it will disable it, and the app won’t work.”

And it’s hard to disagree. College students can be a little more mature than high schoolers and hopefully have the sense to delete the app if it’s causing them emotional harm.

“I’ve seen worse on Facebook or Twitter,” Ilori said.

The virtual feed lends itself to crudity, and Ilori said Yik Yak is “nothing [he] would ever show [his] mom.”

As a casual Yakker, if that’s a thing, I don’t see the huge fuss with the app’s use on college campuses, especially given the app’s regulations. Unpopular or offensive comments will get downvoted into oblivion, and the originator will get served a temporary ban.

“I feel like none of it is really serious,” said Sokolski. “It’s all in good fun.”

As Ilori read through his feed, he laughed at a few messages, such as one that read, “if Tinder has taught me one thing, it’s that any girl can look good in one picture.” Ilori gave that an upvote.

But another comment that disparaged Michael Sam kissing his boyfriend on national television earned a downvote from Ilori.

“Not cool,” he said.