Good thing it’s a leap year, as we needed every day of February in order to get out our second post reflecting on the 75th anniversary of the end of WWII. In our January letter, we explored how the experience of war was captured in the Mem-O-Maps of John Drury. This month, we’ll be examining three campaign maps of The Fifth Armored Division, known as “The Victory Division.”

Mapping the Action – “The Victory Division” on the Move

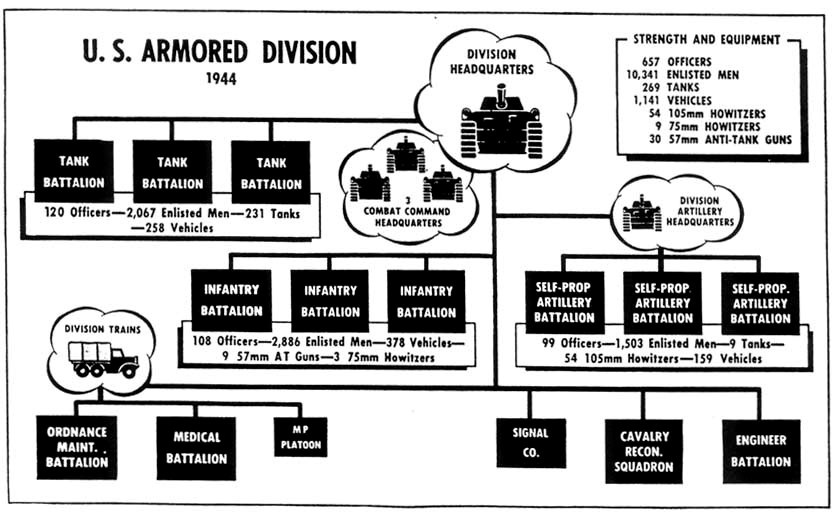

Armored divisions within the United States Army first made their appearance in the early years of the Second World War. The effectiveness of the German blitzkrieg convinced Army high command that a new organizational structure focusing on mobility and stopping power would be necessary to counter the Axis threat. A typical armored division at full strength would be laid out as follows:

The 5th was one of nine such armored divisions that would be created throughout the course of the war. It was activated on October 1, 1941 and shortly thereafter the unit optimistically earned the nickname “The Victory Division,” based on the popular “V for Victory” sign cherished by Europeans under Axis occupation (known today as “The Peace Sign”). The association between the sign and the Roman numeral for the division’s number cemented the name. The first two years of the unit’s career was spent training at Camp Cooke and the Mojave Desert in California. There Major General Lunsford “Bugs” Oliver took command of the unit and oversaw its final year of training in Tennessee and New York before debarking for England on February 10, 1944.

It’s here that the story of The Victory Division is picked up by a series of three maps that were designed and published by the unit’s engineering battalion – the 669th. These maps are emblematic of other unit maps designed during the course of the war in a number of ways. The action is represented matter-of-factly; with lines representing troop movements overlaid on an informal and sparsely detailed map of the theater of operations. Few decorative elements are present and very little attention is paid to extenuating circumstances like weather, allies, native populations or even the enemy. Changes in the composition of the division are also brushed aside – units would constantly be added or dropped depending on the nature of the operation – providing a simplified combat chronicle reinforcing the notion that everything went “according to plan.”

We’ll review the maps chronologically, in the order that they were produced, starting with the advance from Normandy to the Seine River. The image captures a month’s worth of fighting through France in August of 1944. The audience is able to follow the path of the unit from Utah Beach on August 1 as it rolled hundreds of miles through the French countryside on narrow, congested roads (not pictured). Often, the division would be subdivided into Command Companies (CC), the movements of which are also shown. The goal was to get behind the German 7th Army (noted by the enemy line) in the Falaise Gap.

According to a unit history, “To men of the Victory Division, the thrust to Argentan was 15 days and nights of long marches, of increasingly tough battles. It was refueling on the run, eating on the run, sleeping little. It meant communications were almost to the breaking point.” But these struggles are not noted anywhere on the image. Neither are the actions of Lt. Richard Monihan, the first soldier from the 5th to be awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. Monihan carried an injured tank driver for more than 300 yards, holding his carbine in one hand and killing a number of Germans along the way. Possibly, these individual feats of heroism detracted from the image of divisional unity depicted on the map. Or perhaps there was just no room to fit each selfless act due to their frequency while in combat.

Regardless of how the action was depicted, the destruction of the German Army in the Falaise Pocket was a significant Allied victory, and one of the brightest feathers in the cap of the Victory Division. It would lead directly to the liberation of Paris, but unfortunately for the men of the 5th this honor would be granted to the U.S. 4th Infantry Division. After a short period for rest and vehicle maintenance, the Victory Division rolled on.

The second map picks up the action immediately where the first left off – on the 30th of August, 1944. Like the first map, it shows the unit’s movement (though in a smaller scale) by date through the European Theater of Operations (ETO). It was also designed by Technician Robert Buchan and issued to members of the division in March of 1945. Because both maps were published while the war was still ongoing, they exhibit the necessary Army censorship stamp allowing for distribution.

The action starts with the crossing of the Seine in the lower left corner of the map. It was here that the Victory Division was able to finally triumphantly march through the streets of Paris, thronged by adoring crowds that delayed the advance for several hours. From there the various Command Companies sped north towards Belgium, often so quickly that reconnaissance was performed by planes assigned as artillery spotters. General Oliver personally led one armored column nearly 100 miles in a single day (September 2), earning him the Silver Star. Gasoline shortages slowed the advance towards the Meuse, but the Victory Division still managed to secure the first bridgehead across the river (as noted on the map).

After crossing the Meuse, the advance towards Germany continued into Luxembourg during the middle of September. All along the border, Allied troops were closing in on Germany’s western border, but it was The Victory Division who would be the first unit to breach the vaunted Siegfried Line in a series of skirmishes on German territory. Both actions are noted proudly on the map. (Note that this is one rare instance where a subsidiary unit, the 85th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron is recognized for their contribution.) Although the thrust was merely a diversion to draw German defenses away from a planned Allied attack at Aachen, many men in the 5th felt as though the nickname for the division had finally been earned. Both combat commanders earned Bronze Stars for their inspirational leadership.

In early October, the march resumed north. The Victory Division would join other units of the U.S. First Army in the devastating Battle of the Hurtgen Forest (the longest single battle in U.S. Army history), and numerous other lesser engagements in the winter of 1944, until the last major German offensive, the Battle of the Bulge, began in mid-December. Churchill described this last major Allied victory as “”This is undoubtedly the greatest American battle of the war and will, I believe, be regarded as an ever-famous American victory” – thanks in large part to The Victory Division.

The map continues to cover the advance of the 5th into Germany until early March 1945, when the unit was re-assigned to the U.S. Third Army. This reorganization would have offered the men a short respite, and also apparently the opportunity to draw and publish the first two maps we’ve reviewed here.

The third map in the chronicle of the Victory Division was published not by the 669th Engineer Topographical Company, but the 663rd, possibly as a result of the divisional reassignment. It shows the movement of the Division after crossing the Rhine River adjacent to the Ruhr Valley. Most of the actions are considered “mop-ups” as the tanks rolled through Germany, but the destruction of the esteemed Von Clausewitz Panzer Division near the Elbe in April is noted with satisfaction. A nearby text block explains that “upon reaching [the] Elbe, 5th Armd was nearest American division to Hitler’s Berlin.” The German capital, a mere 45 miles away, is shown under a prominent swastika. The Victory Division would continue to clear remaining enemy resistance in the area around the Elbe until V-E Day on May 8th. The map is dated one week later, May 15th, 1945.

There are two other maps that I have found summarizing the action of the 5th Armored Division during WWII. The first is a later reprinting, possibly late 1945, which includes black and white reductions of all three maps mentioned above. A text box in the lower right corner provides a different chronological interpretation of the maps, and includes “actual” dates of action in addition to a brief summary of each. No printer or publisher is noted, and there are no copies listed in OCLC.

The second, published in June of 1945, is titled “The Trek of the 5th Armored” and shows the entirety of the 161-day campaign in the ETO. Like the other maps, it was also drawn by Technician Robert Buchan and published by the office of the division engineer. A yellow shield lists the various armies and corps to which the division was assigned, while small red boxes call out particular achievements.

The combat record of the 5th Armored is one of the most storied of any unit who fought on either side during WWII. The Victory Division led the Normandy breakthrough, sprang the Falaise Gap, was the first to reach the Eure, Seine and Our rivers, and the first to enter Germany. The 5th breached the Siegfried Line, cleared the Hurtgen Forest, and came closer to Berlin than any other American unit. These heroic feats will be forever memorialized in these three maps, which will not only serve as a memory of the campaign, but as a souvenir for those who experienced it firsthand.

What these maps fail to convey is the toll of such heroism. It’s up to the audience to remember that the unit suffered more than 3,000 combat casualties during the war, some of which were to friendly fire. An armored division conjures images of waves of formidable tanks – we must recall that these machines of death were driven almost exclusively by young men who had never before left the safety of their home country. Their fear, courage, and commitment to one another can never be adequately memorialized, cartographically or otherwise.

References:

“5AD Online” The Fifth Armored Division Association, accessed February 2nd 2020. https://www.5ad.org/

G.I. Stories. The Road to Germany: The Story of the 5th Armored Division. Paris: Stars & Stripes, 1945.

Hurley, Emerson and Vic Hillery. Paths of Armor: The 5th Armored Division in WWII. Nashville: Battery Press, 1986.

Schulten, Susan. A History of America in 100 Maps. Illinois: University of Chicago Press, 2018.