ArtSeen

GLORIOUS MADNESS

Art, Improbability, and Jean Dubuffet’s Excursions en no man’s space

New York

Pace GallerySeptember 10 – October 26, 2013

It is ironic that discourse about Jean Dubuffet, that notorious “rebel” of art-land, is so often script-like, resembling ritualized narrative, as if convention could make it possible to contain the complexities of a titan. The essential elements of such a narrative consist of a condensed biographical recitation, statements about the artist’s unrelenting commitment to the rejection of traditional aesthetic values, and perfunctory reference to his invention of art brut. Comparisons to Basquiat are an optional addition.

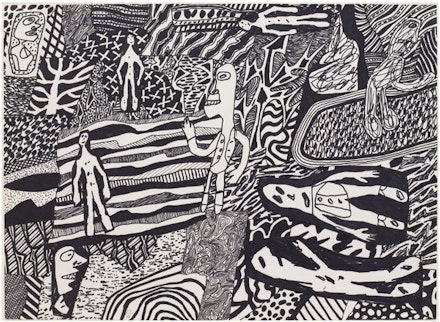

But the security that such convention bestows can geld other narratives, which caper through Dubuffet’s works with coltish impetuosity. The incorporation of these very narratives elevates the Pace Gallery’s current Jean Dubuffet: Excursions en no man’s space from the ‘annual Dubuffet show’ to an odyssey through inky empires that transform “infinite possibility” from a pretty phrase into an experience. The exhibition features 52 works from the last decade of the artist’s life (1975–1985). Forty-four are drawings executed within modest dimensions, primarily in black and white. They are like a procession of improbable worlds, all embodying Dubuffet’s penchant for frank two-dimensionality. Some of these worlds are dimly familiar, populated with relatively pedestrian scenes involving seated women, city streets, or madcap cows, all formed by rakish, seemingly careless lines. Others are neverlands: heavily patterned or perceived through a crazed maelstrom.

But these are not simply drawings; there is nearly always an element of collage—typically human figures—that is physically imposed upon each composition. Yet, these collage additions are cunningly placed chameleons; they seem plausible parts of the drawing rather than elements that have been superimposed upon it. In fact, these collage additions are so seamlessly integrated into the works—both stylistically and in terms of technique—that they do nothing to disrupt the frank two-dimensionality of Dubuffet’s drawings. The collage elements feign fellowship with the surface upon which they have intruded.

Yet the fiction of the uninterrupted surface has a significance beyond simple practicality, for when it is detected the drawings become the visual equivalent of an unrelenting, inexplicably felicitous madness, which uncoils with restless urgency and manufactures landscapes populated with forms that resist all naming, as if language had no words for them.

Collage becomes both the agent and the metaphor for a reality breaking down.

Time turns unknowable; the unity of composition, of objects filling paper worlds, becomes friable. Certainties crumble to precarious speculations. As observed above, the collage drawings are generally of human figures. The uncertainty their inclusion inspires breeds fantasy—not that of the figures themselves, but rather our own: the otherness of the collage figures mirrors the viewer’s own inescapable externality from the work. An unwitting solidarity develops between viewers and collaged figures.

This camaraderie develops for two reasons. First, the figures are like a stylized cast of characters who repeat across compositions. They become recognizable, familiar. Some seem elongated, quizzical phantoms. Others are fleshy dandies with improbable nostrils and buttoned jackets. Many are merely expressive busts. Second, the figures are endowed with a remarkable expressivity. They lament, smirk, gesture emphatically, and conspire. Their emotional range encourages an unlikely intimacy with the viewer. We become unwitting participants in Dubuffet’s ink worlds, explaining his figures through our own fantasies. As we invent narratives to explain these collage-men’s place in unreality, our involvement tacitly makes possible a potential resolution of the composition’s mysteries. We are inculcated into the art as it is inculcated into us.

“Memoration XVI”(1978) exemplifies this process. Its landscape teems with activity. Concentric circles peep from a margin; a path of tiny crosses emerges but leads nowhere; lines cherish arboreal aspirations. Imposed upon this tableau are a series of collaged figures rendered in a variety of styles. Lanky triplets wearing blank expressions fan across one side of the drawing, making a mockery of linear perspective. Elsewhere, a man—the simple outline of his body betrayed by a bellyful of chaotic lines—grimaces. With outstretched arm he supplicates to what seems a harvest of tears girded by stern furrows. Two busts in profile nested in sable mandorlas anchor the edges of the drawing, as if witnesses to the tableau. The figures simultaneously confound explanation and inspire it. Perhaps the men in profile are “real” and the scenes are their disconnected dreams. Or perhaps the drawing is an incoherent composite, a collision of multiple private fantasies.

Excursions is a potentially intoxicating experience. Artists are arguably in the business of forming fantastic visions, and Dubuffet has a talent for railing against aesthetic mores with the conviction of a revolutionary and the whimsy of a child. In these drawings, the tidy separation between art and life deliquesces into a thousand narratives. As we try to unfold the fantasies, we only become a part of them.

Significantly, Excursions ends with color drawings, in which Dubuffet did not employ collage. Undisciplined, surly lines course across the paper, simultaneously cantankerous and bloodless. Still, these works are a boon. Dubuffet once announced his ambition to “animate surface without depth.” The black and white drawings proffer the experience of that improbable animation. The barrenness of the color drawings reveals what happens when those surfaces remain still.