Shedding the stigma around Turkish women and menstruation

(Courtesy of Dr. Berna Fidan / We Need to Talk)

Thousands of seasonal agricultural workers in Turkey don’t have access to clean sanitary products. I’m fighting to change that.

The Turkish Language Institute (TDK) recently updated the definition of the word "dirty" (translated as "kirli" in Turkish) to include "a woman who is menstruating."

This act was a reminder to Turkish girls that menstruation is seen as a taboo. In my own country, something so universal and so natural is seen as something shameful. Periods can be tough to deal with every month. But for some of us who don’t have access to clean sanitary products and who are told menstruating is dirty, periods can be even tougher.

There are thousands of young women and girls in rural Turkey who work as seasonal agricultural workers. From sunrise until sunset, they harvest in the fields. During the year, they migrate throughout the country for different harvest seasons. They work under harsh conditions while having their periods — and most of them don’t have access to clean and safe sanitary products. Sometimes they don’t even have clean water.

I identified this problem when I was a volunteer going through a list of items for an aid package being sent to families in need. Everything was included, from canned food to diapers, but sanitary pads were missing. It was as if these women did not get their periods. It was simply not discussed.

Soon after, I attended the 2016 G(irls)20 Summit in Beijing as the Turkish delegate. The experience was life-changing — and taught me how to address this issue in my community. I learned crucial skills like how to make a pitch. I gained courage, started believing in my capabilities and built an international network, which I proudly call a sisterhood. By listening to other delegates’ stories and ideas, I realized that although we have grown up in different parts of the world, the barriers we face are quite similar. I saw the power of female solidarity. I returned to my home country determined to address the period taboo in my country.

With the support my wonderful family and friends, I founded We Need to Talk in 2016. The initiative targets three groups of women: seasonal agricultural workers, Syrian refugees and pre-teens who are going to remote schools in rural Turkey. Through donations and sponsorships, we provide young women and girls with enough sanitary pads to last a harvest season or a semester. We inform them about menstruation through our volunteer doctors. We have Q&A sessions. And, most importantly, we build a safe environment to talk about menstruation. That is why I named the initiative “We Need to Talk.” We need to talk about menstruation and destroy the stigma around it.

Building this project has been a beautiful journey. My first supporters were my parents. Family members collected donations. My sister Pırıl and my best friends volunteered for the fields projects. A friend designed our logo as her final project. A young woman named Bahar from the U.S. reached out through a common friend — now she is my partner for organizing new field projects.

One of my first projects was in the slums of Ankara, the capital of Turkey, where we visited middle schools with a volunteer team of high school students. We talked about puberty, taught tips about personal hygiene and discussed how normal periods are — with both boys and girls.

Since then, we have organized more than five field projects where volunteer doctors inform girls and women about menstruation and sexual and reproductive health. We hold Q&A sessions, do exercises on personal hygiene, distribute a sufficient amount of sanitary pads to last throughout the harvest season and show how to use and dispose sanitary pads. On special dates, we add informative sessions. On November 25th, International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women, a team of lawyers gave a mini-seminar about legal steps domestic violence victims or witnesses can take and possible remedies.

There certainly have been challenges starting this initiative. In certain conservative neighborhoods where we were concerned about the reactions, we distributed sanitary pads in black plastic bags. We feared that our open discussion on periods and sexual and reproductive health could provoke extreme conservatives who think period talk is unchaste. Hiding the products was contradictory to our main aim and it was a difficult decision. However, we have to pick our battles and decided that safely bringing supplies to the young women in need was the priority.

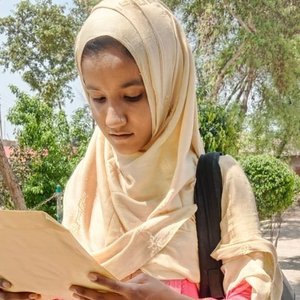

17-year-old Fatma helping her family for the peanut harvest. (Courtesy of Dr. Berna Fidan / We Need to Talk)

I have met incredible girls through this initiative who are trying to support their families under very harsh conditions. Their lives are not easy, and honestly, I can’t say that providing them sanitary pads has changed their lives completely. Not even close.

However, through our work, we start honest conversations about menstruation for the first time. We explain why menstruation is not something to be ashamed of and definitely not “dirty.” We remind mothers to have discussions with their daughters about sexual and reproductive health. And we help these girls and women embrace their bodies.

We have reached more than 2,000 young women and girls in total and we have exciting, upcoming projects and collaborations with big brands. There is a long way to go — but we’re taking important steps towards a brighter future. Access to sanitary products is not only about hygiene, but also about dignity. And the We Need to Talk team believes every girl deserves dignity.

Read more

Read more